By Lambert Strether of Corrente

As readers may know, I was a model railroader when young, and I still buy Model Railroader. The picture of America I have is very much like the sort of town that one might model in the steam-to-diesel era, and much like the town I grew up in. My model town, besides the main line and the yard, would have spurs for a lot of small industries, like the local brewery, or the local lumberyard, or the local meatpacking plant. All that is now gone; today one would model giant unit trains of coal, or miles-long trains of containers cars loaded with consumer goods, and they’d roll through the town without stopping. Gone from my model town too, after deindustrialization, would be two- or-three story brick factories: machine shops, machine tool manufacturers, and foundries. The manufacturing base.

If I lived in the past, I might assume that re-industrialization would be as easy as building a new plant and plopping it down in my model town; “build it and they will come.” But this America is not that America. Things aren’t that frictionless. They are not, because of a concept that comes with the seventy five-cent word hysteresis attached, covered here in 2015. Martin Wolf wrote:

“Hysteresis” — the impact of past experience on subsequent performance — is very powerful. Possible causes of hysteresis include: the effect of prolonged joblessness on employability; slowdowns in investment; declines in the capacity of the financial sector to support innovation; and a pervasive loss of animal spirits.

(To “loss of animal spirits” in the entrepreneurial classes we might add “deaths of despair” in the working class.) And if there were a lot of people like me, living in the past — in a world of illusion — that too would would cause hysteresis, because we would make good choices, whether for individual careers, at the investment level, or at the policy level, only at random.

Our current discourse on a manufacturing renaissance is marked by a failure to take hysteresis into account. First, I’m select some representative voices from the discourse. Then, I will present a bracing article from Industry Week, “Is US Manufacturing Losing Its Toolbox?” I’ll conclude by merely alluding to some remedies. (I’m sure there’s a post to be written comparing the policy positions of all the candidate on manufacturing in detail, but this is not that post.)

The first voice: Donald Trump. From “‘We’re Finally Rebuilding Our Country’: President Trump Addresses National Electrical Contractors Association Convention” (2018):

“We’re in the midst of a manufacturing renaissance — something which nobody thought you’d hear,” Trump said. “We’re finally rebuilding our country, and we are doing it with American aluminum, American steel and with our great electrical contractors,” said Trump, adding that the original NAFTA deal “stole our dignity as a country.”

The second voice: Elizabeth Warren. From “The Coming Economic Crash — And How to Stop It” (2019):

Despite Trump’s promises of a manufacturing “renaissance,” the country is now in a manufacturing recession. The Federal Reserve just reported that the manufacturing sector had a second straight quarter of decline, falling below Wall Street’s expectations. And for the first time ever, the average hourly wage for manufacturing workers has dropped below the national average.

(One might quibble that a manufacturing renaissance is not immune from the business cycle.) A fourth voice: Trump campaign surrogate David Urban, “Trump has kept his promise to revive manufacturing” (2019):

Amazingly, under Trump, America has experienced a 2½-year manufacturing jobs boom. More Americans are now employed in well-paying manufacturing positions than before the Great Recession. The miracle hasn’t slowed. The latest jobs report continues to show robust manufacturing growth, with manufacturing job creation beating economists’ expectations, adding the most jobs since January.

Obviously, the rebound in American manufacturing didn’t happen magically; it came from Trump following through on his campaign promises — paring back job-killing regulations, cutting taxes on businesses and middle-class taxpayers, and implementing trade policies that protect American workers from foreign trade cheaters.

Then again, from the New York Times, “Trump Promised a Manufacturing Renaissance. What Happens in 2020 in Places That Lost Those Jobs?” (2019):

But nothing has reversed the decline of the county’s manufacturing base. From January 2017 to December 2018, it lost nearly 9 percent of its manufacturing jobs, and 17 other counties in Michigan that Mr. Trump carried have experienced similar losses, according to a newly updated analysis of employment data by the Brookings Institution.

Perhaps the best reality check — beyond looking at our operational capacity, as we are about to do — is to check what the people who will be called upon to do the work might think. From Industry Week, “Many Parents Undervalue Manufacturing as a Career for Their Children” (2018):

A mere 20% of parents associate desirable pay with a career in manufacturing, while research shows manufacturing workers actually earn 13%more than comparable workers in other industries.

If there were a manufacturing renaissance, then parents’ expectations salaries would be more in line with reality (in other words, they exhibit hysteresis).

Another good reality check is what we can actually do (our operational capacity). Here is Tim Cook explaining why Apple ended up not manufacturing in the United States (from J-LS’s post). From Inc.:

[TIM COOK;] “The products we do require really advanced tooling, and the precision that you have to have, the tooling and working with the materials that we do are state of the art. And the tooling skill is very deep here. In the US you could have a meeting of tooling engineers and I’m not sure we could fill the room. In China you could fill multiple football fields.

“The vocational expertise is very very deep here, and I give the education system a lot of credit for continuing to push on that even when others were de-emphasizing vocational. Now I think many countries in the world have woke up and said this is a key thing and we’ve got to correct that. China called that right from the beginning.”

With Cook’s views in mind, let’s turn to the slap of cold water administered by Michael Collins in Industry Week, “Is US Manufacturing Losing Its Toolbox?“:

So are we really in the long-hoped-for manufacturing renaissance? The agency with the most accurate predictions on the future of jobs is the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Their projection to 2026 shows that US manufacturing sector will lose 736,000 manufacturing jobs. I spoke with BLS economists James Franklin and Kathleen Greene, who made the projections, and they were unwavering in their conclusion for a decline of manufacturing jobs.

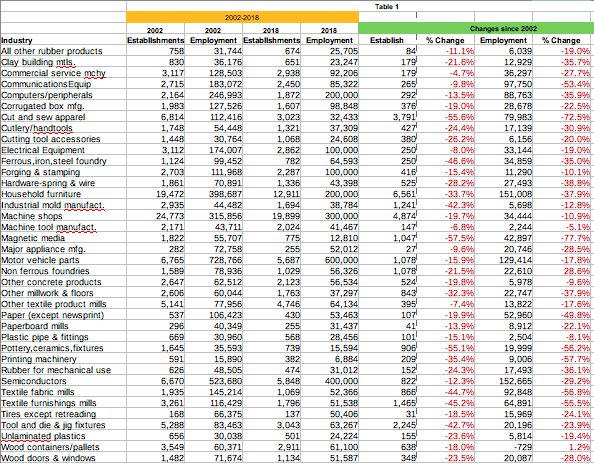

This prompted me to look deeper into the renaissance idea, so I investigated the changes in employment and establishments in 38 manufacturing North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) industries from 2002 to 2018. I really hoped that the optimists were right about the manufacturing renaissance, but the data I collected in Table 1 (see link) shows some inconvenient truths—that 37 out of the 38 manufacturing industries are declining in terms of both number of plants and employees.

So, yeah. Mirage.

I reformatted Table I so I could mess about with it in LibreOffice. Here it is, in its original form:

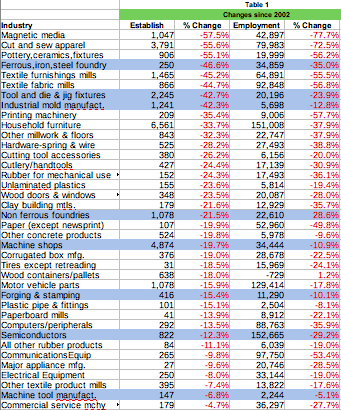

And here are the changes in the NAICS manufacturing categories sorted by losses to firms:

(“1,047” in the first data cell means that number of establishments were closed, hence “-57.5%” in the second data cell is negative.) There are many fascinating stories — tragedies, really — behind these statistics. We can see the collapse of the apparel industry in “Cut and sew apparel,” (-55.6%), “textile furnishings mills” (-45.2%), and “textile fabric mills” (‘44.7%). We can see the decline of Maine’s pulp paper industry in “Paper (except newsprint)” (-19.9%). What’s doing well? Wood containers/pallets (firms down 18.0% but employment up 1%). Gotta pack those consumer goods coming in from China somehow!

However, I’ve highlighted the categories that really concern Collins in blue; they all have to do with, as Cook calls it, tooling. Collins writes:

But the most perplexing of these declining industries are the ones that are fundamental to making other manufactured products. These are industries like machining, machine tools, mold making, tool and die, semiconductors, forging, and foundries. It is difficult to see how we can achieve a manufacturing renaissance while these critical industries continue to decline… Machine tools. These are the master machines that make other machines and products…. Machine Shops. Machining is essential to hundreds of industries and thousands of products from products as tiny as a machine screw and as large as a turbine bearing for a dam. Machining is absolutely essential for all industrial products but is also used in consumer products. Machining. Two classes of machinists that are critical to manufacturing are tool and die makers and mold makers…. Industrial mold companies lost 1,241 shops (42.7%) and 5,968 workers (12%) between 2002 and 2018. The big question is, since a good deal of machining is now done overseas, is it possible to support all of the industries and companies who need machined products in the U.S by only using foreign suppliers? Foundries. The process of making parts by pouring metal to make a casting is ubiquitous and is used in the machinery, automotive, pipe, fitting, railroad equipment, valve, and pump industries. Castings are also used in everything from heart valves to aircraft carrier propellers and in every home for bathtubs, sinks, fixtures, and furnaces… Forging and Stamping. The demand for forging and stampings has been declining by the industry’s major downstream markets, which include aerospace, agricultural machinery and oil and gas machinery. Additionally, the world prices of steel, and nonferrous metals have been volatile, making it hard for the industry to secure stable purchasing contracts… Semiconductors. Semiconductors are absolutely fundamental to the electronics and computer industries… One of the big problems is that when the manufacture of semiconductors moves overseas, research and development goes with it. If the decline continues the U.S. is in danger of losing its innovative edge in electronics and computers.

Collins concludes:

A strong part of the new optimism that US manufacturing is in a renaissance is driven by digital revolution that includes progress in robotics, artificial intelligence, 3D printing, data analytics, and other digital advances. The digital revolution has great potential, but economic numbers show that it is not yet a reality. In fact, economic data from the BLS shows that since 2007, productivity growth has averaged only 1.3% growth. …[T]he biggest problem as shown in BLS data shows that 38 manufacturing industries continue to decline and nine of 10 of these industries are the critical industries that are fundamental to the manufacturing process. The digital revolution is not going to help if we eventually lose the industry.

A tooling firm closes, and a complex organism withers. The machinery is sold, sent to the scrapyard, or rusts in place. The manuals are tossed. The managers retire and the workers disperse, taking their skills and knowledge with them. The bowling alley closes. The houses sell at a loss, or won’t see at all. Others, no doubt offshore, get the contracts, the customers, and the knowledge flow that goes with all that. All this causes hysteresis. “The impact of past experience on subsequent performance” cannot be undone simply by helicoptering a new plant in place and offering some tax incentives! To begin with, why would the workers come back?

So, when I see no doubt well-meant plans like Warren’s “Economic Patriotism” — and not to pick on Warren — I’m skeptical. I’m not sure it’s enough. Here are her bullet points:

- More actively managing our currency value to promote exports and domestic manufacturing.

- Leveraging federal R&D to create domestic jobs and sustainable investments in the future.

- Production stemming from federally funded research should take place in the United States

- Taxpayers should be able to capture the upside of their research investments if they result in profitable enterprises.

- R&D investments must be spread across every region of the country, not focused on only a few coastal cities.

- Increasing export promotion to match the efforts of our competitors.

- Deploying the massive purchasing power of the federal government to create markets for American-made products.

- Restructuring worker training programs to deliver real results for American workers and American companies.

- Dramatically scale up apprenticeship programs.

- Institute new sectoral training programs.

There’s a lot to like here, but will these efforts really solve the hysteresis that’s causing our tooling problem? Just spit-balling here, but I’d think about doing more. Start with the perspective that our tooling must be, as much as possible, domestic. (“If your business depends on a platform, you don’t have a business.” Similarly, if your industrial base depends on the tooling of others, it’s not an industrial base.) As tooling ramps up, our costs will be higher. Therefore, consider tariff walls, as used by other developing nations when they industrialized. Apprenticeships and training are good, but why not consider skills-based immigration that brings in the worker we’d otherwise have to wait to train? Further, simply “training” workers and then having MBAs run the firms is a recipe for disaster; management needs to be provided, too. Finally, something needs to be done to bring the best and brightest into manufacturing, as opposed to having them work on Wall Street, or devise software that cheats customers with dark patterns. It’s simply not clear to me that a market-based solution — again, not to pick on her — like Warren’s (“sustainable investments,” “research investments,” “R&D investments,” “export promotion,” and “purchasing power”) meets the case. It is true that Warren also advocates a Department of Economic Development “that will have a single goal: creating and defending good American jobs.” I’m not sure that’s meaningful absent an actual industrial policy, democratically arrived at, and a mobilized population (which is what the Green New Deal ought to do).

Whatever was invested in China over the last 20 or 30 years would have to be invested in the US.

I don’t understand why any investor, or the stock market, would provide that level of investment. Where would be the return?

The US built its industrial base on 150 years of investment before 1970, because it has a continent in which to expand, and a determination not to become a UK vassal state, again.

And then there is climate change…..where China’s new industrial areas will become threatened by rising sea levels…

In a sense, Synoia’s remarks vindicate Trump’s bogus assertion that trade war is necessary for national security. At least in this sector, he is probably correct about the security risk. Of course, his disastrous solution is something he overheard on FoxNews from his now dimwit economic advisor – the one who would not recognize a recession if it bit him in the nose.

Can we really make guns and bullets and tanks and planes without US manufacturing? We would probably have to depend on allies for that. Alas, we are not so palzy-walzy with China. There is Germany – a stalwart of machining savvy – but Trump would rather mock German leaders on Twitter than do biz with DE.

Trump’s bogus assertions could only be vindicated if he enunciated an industrial policy, including the missing skills, training and money to repatriate manufacturing, which destroys the investment by our beloved multinationals in Mexico, China and elsewhere.

I was gently pointing out that Trump has his head so far up his a.., that one can hear him talking.

It is true that one must blow apart the pro-globalist consensus, and this Trump has done. (Not passing TPP was a clear win, and we should take that win. So far as I know, TTiP is off the front burner now, too). It is also true that tariffs have to part of any solution. But beyond this, coherence eludes the administration. Clearly, industrial policy is part of the solution. Warren’s plan doesn’t provide it, either.

I understand that such talk is considered old fashioned, these days,lol…but does “Industrial Policy” include things like “paying the Workers”…or even just “Not Screwing the Workers”?

Or is that a separate hill to climb?

NC and NC Commentariat is excluded from this snark and cynicism.

I think of my grandad’s small manufacturing business in Houston…we built the brewery, the box plants the can plants and a lot of the refineries, as well as a whole bunch of other stuff that’s now rusting away.

but a big part of his Ethos was taking care of his workers.

Talking about that ethos, today, anywhere else but here, seems somehow quaint.

after 50 years of financialised globalisation and Free Capital, I think that Ethos needs to be stated right out front, and as clear as a bell, so the lawyers and pols can’t wiggle out of it.

like the mentioned “job training”, but larded with MBA’s running the show…that’s what the people who will write the rules Believe…”trade is always good!”, “maximise transactions!”, etc.

the entire Belief System we operate under…most often without thought…needs to go.

otherwise, any “reindustrialisation” will be as i have feared was the plan all along: to wait until we’re desperate enough to arbitrage, and will work for pennies to provide the Chinese Middle Class with cheap plastic pumpkins.

Thanks for this analysis. And the word Hysteresis. Could be the dilution of trauma, but it never goes away. You’d think it would function like a social vaccine, no? But clearly the only thing that can cure it is equity and security. Where’s our HAL? We need a computer to maintain social equality. I also agree that Liz’s Economic Patriotism is puffery in most places. Increasing exports is an absurd goal when the world is deindustrializing. Becoming nationally self-sufficient is a much better goal. Foundries and forges are the biggest polluters so their use will be modest. I remember only about 2 or 3 years ago we were all very smug about the fact that China had no machine tool industry. The Chinese have really knocked us all back on our heels. But my take on all this is it is time for change and we shouldn’t fight the last war. We should adapt using all our science and technology and creativity. We should do Environmental manufacturing. How many engineering, physics, agriculture, aquaculture, chemistry departments (to name a few) couldn’t supply us with state of the art technology to turn all our exorbitant recycling into new useful machinery? It might be expensive when we can’t externalize the heat, pollution and waste as we used to under old fashioned machine manufacturing, but the payoff for the environment will be earth-changing. And we might even learn to survive.

Our current industrial policy consists of:

* Allowing big corporations to avoid taxes

* Destroying/marginalizing labor unions

* Being in bed with the Chambers of COmmerce

* Hand outs to yuuge corporations (via sweetheart contracts)

*Price supports to large corporate farmers

*Enforcing patents, trademarks for yuuge corporations

*Big finance to large corporations and saving TBTF banks

^Bankruptcy laws that favor big business

*NAFTA and other trade treaties to help multinationals

*H1B and other visas that reduce labor costs for big employers

*Not prosecuting corps that employee undocumented works

*Destroyng economies of developing countries to favor our exports

*fomenting unrest wherever industries are nationalized to help our corps

*Aggresively defending the almighty dollar by every means possible

*Funnelling tax payers funds to universities for research to help big Pharma

*Making sure our Insurance and RE sectors are subsidized through loans and bailouts

I’m sure there are more but I can’t think of all of them.

Who says we don’t have an industrial policy?

“Oh”;

Thank you, thank you, thank you!

The bottom line!

As an added comment I just can’t believe that this is what would not have been expected with any sniff of “globalization” back in it’s birthing 30 years ago. What did Americans expect? We dominated the post WW2 years in good manufacturing jobs while most of the world was licking their wounds from that war; the rest of the world has caught up and passed us by assisted by the globalization of flows of funds with the click of a mouse. Labor can’t move like that. The “Renaissance” of Jobs” is a farce and an illusion. Unless the US comes up with something so new in manufacturing and can control that process for decades to come it is descending more an more into a 3rd world status; a super wealthy small upper class and the rest in “rickshaw” land. Even trade “wars” will not help.

The Chinese government has a pact with its population: the government makes sure the economy is structured to provide jobs and the people promise not to overturn the government through revolution.

When it is existential, then it becomes important. The US has simply stated that “The Market” will determine what makes sense. Nothing existential there.

So people became disposal, fungible assets for the MBAs to run their spreadsheet numbers on. For years they could assume that they could simply rehire skilled labor. However, that skilled labor is retiring or becoming out of date, so the workers are no longer fungible. The bleating begins about the lack of skilled labor because “somebody else” was responsible for providing the skilled labor training. So most US firms have gone the Tim Cook route and out-sourced to other countries that have trained workers and engineers over the past 20 years.

It will require a major paradigm shift from both government and corporations to change the trends.

The Chinese government has a pact with its population: the government makes sure the economy is structured to provide jobs and the people promise not to overturn the government through revolution.

The American government has a pact with its population: the government makes sure the economy is moved abroad and promises to kill the people if they attempt to overturn the government through revolution.

Personally, I prefer the first option.

And it’s not just “the government” — it’s more the other MIC: The Marketing Importing Complex. Apple is worth nearly a trillion dollars, that’s 1/12 of China’s GDP!

They could have used not so much of that money at all to train several workforces and build many factories. But that’s not what brings in the big executive compensation.

And related to the loss of a skilled worker base is the loss of patents needed to compete. Although many patents for original inventions still originate in the US, subsequent patents on improvements originate not in a lab, but from the shop floor. For example, the original machinery for producing microchips may well have originated here, but as that industry moved overseas, so did the patents on improvements. I doubt that we could compete in the manufacture of LEDs, flat-screen TVs or monitors etc. even if we could do so economically: the patents for the machines to make these things now reside overseas, in the hands of those manufacturers that have been improving them for decades.

Good little post. A timely reminder that we’ve been bleeding those jobs and it’s an ongoing process, but we’ve already bled a lot of them away.

It’s now been 20 years since PNTR with China. The direction has become clear. It’s going to take a tremendous amount of political will to change that direction. There are early signs of a change, but not enough, yet.

Tariffs will need to be part of the answer. Fiscal policy and federal contracts will need to be part of it. New regulatory bodies with new powers to enforce federal policy, too.

Also, my inner-Matt Stoller would like to remind us all that anti-monopoly is going to need a prominent role, too. The business model of private equity has been to buy up a all competitors in a particular niche, become a single supplier to the government, outsource to cut costs. Then, jack up prices to boost margins.

‘skills-based immigration’ doesn’t have a good track record. Look at H1B visas. They’ve been turned into a vehicle to import low wage labor, and then enable outsourcing.

> ‘skills-based immigration’ doesn’t have a good track record. Look at H1B visas. They’ve been turned into a vehicle to import low wage labor, and then enable outsourcing.

They work for Canada, so we should copy them.

The US H1B is an employment based non-immigrant visa, easy for corporations to use for their own purposes – especially when the person’s right to reside relies upon their continued employment at their sponsoring employer.

Canada has a points based immigration system for the majority of immigrants (others are family reunification etc.) that is not employment based. Those getting the required points are given permanent residency (with a path to citizenship within 4 years). They can move from job to job at will. Its how I became a Canadian citizen.

Much less exploitable than a US H1B Visa holder.

With all the scam online business listings, it also gives people the impression of a business environment that is active…but it’s a con.

I was thinking about this the other day in response to the Economist’s recent article about a new boom in employment.

Does anyone know if scam artists, ransomeware senders, illegal salvagers, and stolen goods fencers would be counted as part of official employment statistics?

There’s a whole section of the economy that is growing right now based upon illegally raiding closed down big box stores and selling the goods on eBay. Similarly, just like in any other time when inequality is high, scams and efforts to deceive others for profit are on the rise.

That’s perceptive. I would bet Manhattan on Google maps has many, many more “firms” than Manhattan at street level, where you see a “For Rent” sign on every block.

An idea for a fun chart: how many types of marketing jobs are there now?

? However, I’ve highlighted the categories that really concern Collins in blue; they all have to do with, as Cook calls it, tooking. ?

Not a sophisticate, so I assumed – tooking – was a term of art.

Pretty sure it was one of many misspellings, and that what was meant was “tooling.” Hard to take articles seriously when the writer doesn’t even bother to run them through spellcheck.

Someone piss on your cornflakes this morning?

It’s a big Internet. I hope you find the perfection you seek elsewhere.

+10000

Somebody up there never read The Grauniad, nor appreciated how it came to earn that particular nickname. Hard to take comments seriously when the writer doesn’t even bother to consider the proverb “let he who is without sin cast the first snote”.

And Clive wins Teh Interwebz today.

The bad news is that what is also lost is a caring-about-getting-details-right culture. Nearly extinct, in fact, at the business level, and I would sadly include engineering-intensive businesses (based on what little I have experienced.)

The good news is that North America has plenty of the human resources (and physical plant) we are talking about, mostly within a short drive of the border, even.

I would actually be more inclined to despair about the former than the latter.

An alternative view that is hard to evaluate from this data…we should be looking a domestic manufacturing economic value, not jobs. While loss of jobs is certainly bad, isn’t it ameliorated if the manufacturing activity is taking place in the US? Hard to evaluate with given data.

Not necessarily. The problem with trying to evaluate “value” in trans-national Apple- or Walmart-style value chains is that the dominant player (Apple, Walmart) recognizes almost all of the value-added. (One could add “… regardless of where that value is created” but, as Veblen pointed out a hundred years ago, there is no way to disentangle productive value from “buying and selling,” so there is no “correct” way to assign value.)

The fact that Foxconn in China pays really low wages and has relatively tight profit margins leads to the conclusion that the value contribution per capita of Apple employees (because contractors don’t create value either) is if I recall correctly several million dollars per employee. If that manufacturing work was done in the U.S., the value-per-employee would be much lower (still very high) but the wages paid, and worker living standards, would be much higher. (This would also be true, though to a lesser extent, if they doubled or tripled the wages of their Foxconn workforce in China.)

On top of this, of course, are the income-recognition and tax games that multinationals play. Economists know about these but somehow seem to think national data provide (a different set of?) “true” representations of value-added anyway.

It is interesting to know that for furniture the timber is felled here in the US, the timber milled into lumber here, kiln dried here, packed into containers here, shipped from here to China, turned into furniture, knocked down, shipped here and reassembled here.

Not sure where the savings are but I suspect that the goal was to maximize profit and minimize taxes.

Of course no one will be left to buy furniture except on credit.

I’ve been thinking about not only the manufacture of things like that but the craftsmanship that went into it (once upon a time).

I noticed the street lamps in Hollywood. The older ones that still work are black and elegantly designed steel. The part holding the lamp, the steel is bent like an arm flexing biceps.

The newer ones are taller. But just steel, bland, straight, can see them anywhere…

Now you’re talking . . . MMT

(Material Meets Tool X sales) – expenses = profit or loss

Got tooling?

> . . . Apprenticeships and training are good, but why not consider skills-based immigration that brings in the worker we’d otherwise have to wait to train?

Piss off. After the tooling industry was destroyed by cheap Chinese labor, you want to bring them in to further destroy it or take it over?

Cheap Chinese labor in fact offshore labor is at best a canard and generally not far from a deception which repeated often enough becomes fact.

A good approach is to look at the labor quotient that is the cost of labor necessary to create a finished product.

For example in aluminum manufacture using the Hall process to reduce bauxite the majority of the cost is in electricity perhaps as much as 90%+ and labor cost is around 5%. So any manger worth his paycheck moves the operation to a a region of low power cost e.g. Iceland, Bonneville power territory, TVA. Labor cost is minimal perhaps 5%.

At one time the labor cost for textiles was around 17 % with the aim of the mills to drive the labor quotient to 12% through automation.

In addition if labor costs were the driving force in manufacturing it would be reasonable for all of U.S, manufacturing to relocate to low wage states such as Mississippi or the Dakotas.

And one should note that the multinationals are not shy of hiring U.S. labor at their factories here in the US.

The goal of U.S. corporations is to take advantage of tariffs (taxes) and the greater flexibility of accounting in offshore locations.

See Bluescope here in Oz shifting more Mfg to the U.S. due to energy costs.

My lived experience tells a different story..

Before my ex customers and I parted ways, they used to get me to quote tooling work and then send the work to China. The reason given, my price was too high and they could get if for a fraction of that in China. No, it wouldn’t be the same tool, but they liked to think they were getting an equivalent.

Before I gave up on them and fired my rotten customers, I used to ask “where is my one dollar per day cop”, my one dollar per day teacher, my one dollar per day politician” so that my cost are in line with the Chinese? That drew a blank stare every time with no answer.

Tooling work is labor intensive and not comparable to generating electric power.

I view tooling as society’s precious metal. It is the “means of production”. The lawyers and politicians (one and the same from my viewpoint) running the country for their own benefit (they could not care less about you or me) make their money by charging the victim that darkens their doorway $500 bucks an hour. For them, they produce nothing and take it all, and their view of wealth generation is distorted by their occupation. They are quick to hand money to the biggest corporations to make them richer (see Wal-Mart and Amazon’s massive billions in subsidies), but a little guy like me can rot in hell.

Globalization is a disaster, no matter where one cares to look.

> I view tooling as society’s precious metal. It is the “means of production”.

“Constant capital” is what The Bearded one called it, I believe. But yes.

AMEN. My lived hell for the last 30 years… And then some smug right wing nut job tells me I’m just jealous…

Send the work to China has been dying since 2005. Didn’t you notice? US heavy manufacturing has ex-material extraction almost looks now where it was in 2000. That isn’t necessarily a good thing. Debt driven illusions can kill.

One operation as an example is not apply to all manufacturing.

> After the tooling industry was destroyed by cheap Chinese labor, you want to bring them in to further destroy it or take it over?

No, I don’t. If there’s a sane industrial policy, then (a) there’s more than enough work for everybody and (b) we can pay “prevailing wages” as we ought to do. I think in this case the country is in such a hole we can add on, and the game is not zero sum. Not the same as, say, meatpacking.

Big if, there. The managers and owners that would influence industrial policy will waste no time in bringing over 10,000 or 100,000 or however many they wanted, and swamp the industry with cheap labor.

According to Cook, there are millions upon millions of toolmakers and machinists in China, so even a million wouldn’t be missed. Toolmaking becomes the new meatpacking.

My bet is there will be no sane industrial policy.

There isn’t going to be an industrial policy. Because markets.

A possible “Black Swan” in all this national manufacturing quandry is the fragility of the supply chains involved. Today, the costs of shipping materials and goods across an entire ocean are managed through scale, (Embiggening Shipping Incorporated,) computerized scheduling, (Just In Time Ordering,) and cheap energy, (Fearless Fred’s Fracking Et Cie.) Any one of those inputs could go asymmetric and make the exercise of Materials Globalization uneconomic. Then people would have to either pay more for something or do without. Either outcome would reduce aggregate economic activity in the nation. The social result would be another example of ‘hystereisis,’ people remembering what their and family members standards of living once were, and taking that for a ‘normal’ that has been stolen from them. A process similar to that which preceded the French Revolution will be in play.

It also helps to have clusters of similar industries in the same location. This gives new companies an area with lots of folks with the appropriate skills. We lost these “centers of manufacturing excellence” when so much of it got off-shored. It’ll take significant efforts to bring them back.

An excellent additional aspect!

You are of course correct but good people have been making this argument for the last 40 years with virtually no impact on corporate behavior. I’m no expert in Chinese manufacturing but I would have to think by now the technical capacity in China – not saying everywhere but certainly in large parts of the export sector – is very high. Yet the wages and working conditions are still terrible. So much for productivity = wages.

True. In a stable environment, labour availability ‘drives’ wages. That was the secret the Unions levered to success. Restrict the supply of labour and squeeze the owners. Find a “fair” balance and the Golden Age ensues. The “fair” part of that equation was redefined, and here we are.

A risible ‘Snark’ if you will.

Lambert claims to have been a “model railroader” when young. Such virtue in one so young! I, poor deplorable, primarily associated with louche and gauche railroaders and tabletop gamers. So it is understandable that he grabbed the Iridium Ring while I merely took a circular ride. The “Eternal Return” in all it’s refulgent glory. (I should meditate more on my exorcising of ‘amor fati.’)

Funny!

To quote a friend who hires workers for factories in the US and China,

“Manufacturing in the US is a nightmare. At our facility our only requirement for assemblers was a high school degree, US citizenship, passing a drug and criminal background check and then passing a simple assembly test: looking at an assembly engineering drawing and then putting the components together. While the vast majority of Americans were unable to complete the assembly test, in China they completed it in half the time and 100% of applicants passed. An assembler position in the US would average 30 interviews a day and get 29 rejections, not to mention all the HR hassles of assemblers walking off shift, excessive lateness, stealing from work, slow work speed and poor attitudes. The position starts at $12 an hour in flyover country which is pretty reasonable compared to other jobs that only require a GED and no prior work experience and offers medical, dental and annual raises with plenty of opportunity to move up in the company and earn the average salary for a Production Assembler, $33,029 in US, if they stay for five years.

Identical positions in China pay the same wages as other positions there with only a high school degree and no work experience. Yet the applicant quality is much higher and this applies to the white collar support professionals: schedulers, quality inspectors, equipment testers and calibrators, engineers, supply chain managers, account managers, sales. Their labor quality is simply higher. At the end of the day, high-end and middling manufacturing is not moving to the US or Mexico because average people in flyover country are dumb as rocks.”

1. Just curious but does your friend say what the wages are in the Chinese plants? Do they reflect the quality of the applicant pool? Based on the talent levels you describe, they should all be making $100K/yr. At least 50. And not having to live in dormitories. Maybe the fact that your friend has access to such a talented workforce at starvation wages has something to do with workers not really being free? Why do we call it free trade, anyway?

2. I have no reason to doubt the fact set you describe. But it could have turned out differently, and the reason it didn’t was that companies that were developed and initially made huge profits in this country decided to take the jobs elsewhere because they could make even huger profits. Everything else flowed from that.

> Their labor quality is simply higher

Thanks, as Tim Cook points out, to the quality of Chinese public education, which our own elites have been busily destroying. It’s almost like after the neoliberals took over in the mid-70s they “burned the boats” so there was no way back to what the country was; a more vivid way of saying “hysteresis,” I suppose.

$33K if you stay five years, how friggin generous. I wonder, how much is “your friend” pulling down shuttling between US and China? I’ll bet it’s a lot closer to $330K than $33K.

$12 an hour is a joke and you will get what you pay for. “Flyover” country or not, but I suppose the distinction is important to bigots that want to mentally justify exploiting the class.

I know plenty of people that bust their ass in multiple jobs for not much more than your “friends” generous $12 an hour and they are hardly “dumb as rocks”. Maybe “your friend” needs to look at his recruiting skills.

My rural neighbors and friends in southern Michigan are these $12 hour workers your friend references. Did your friend mention “mandatory overtime”? or “zero hours”?. What this means is when you go to your job at 7am you may be sent home at 9 (they have to pay you for 2hours during which you clean the plant), or at 2pm when your shift ends in an hour they let you know they want you to stay until 5. Forget a weekend, you find out on Friday if you have to work Saturday, on Saturday you find out about Sunday. I have friends that have worked 74 days in a row with no day off, then they are on temporary shutdown for 20 day (unpaid of course!) while the plant re-tools or absorbs unsold inventory. Your work week is driven by the whims and profits of the the corporation.

There is no security in these jobs, not weekly, monthly and certainly not as a career. The factory may close or re-locate abruptly due to the some corporate buy-out, merger, or re-location to a more lucrative tax-free/low labor pay location. Sometimes the physical location in your little town re-opens with a new name, new owner, usually lower pay, but always the same insecure employment story.

These are not jobs you would encourage your children to take on as a career, jobs you build families and buy homes with.

I’ve designed and installed measurement/control equipment in exactly the type of US facility this commenter is describing. The reason the applicants are “dumb as rocks” is that the company culture drives all others away. Why go to a sh#tty factory with no windows, weird hours, and an obnoxious tailorist environment, when you could get paid the same or more at a car shop (even just the guy/ gal washing the cars) or a construction (even just a laborer). The bottom level of factory work in the US sucks. Hiring managers know anyone who is worth anything will quit in a month or two so they set up the process to subtly screen for people that will stay (i.e. already had the self esteem wrung out of them by previous experiences). Techs have it a bit better, since they actually have a path up the ladder that isn’t a lie. But the environment is deeply depressing, like a bad stereotype of the 1930s. I honestly hate going to US factories.

If you fish on the bottom, you catch bottom fish. What’s the problem? $12/hr maybe OK for college kids looking for a summer job; for me its a slap in the face. 30 yrs millwright/welder/fabrication and machining. 3 trade schools at own expense; own tools. No drugs whatsoever, ever. You want people to be professionals you have to treat them like that, and that begins with the pay package. Maybe your friend needs to be told this, verbatim.

Thinking over Lambert’s last paragraph, can the economic system that got us into this mess also be capable of getting us out of it? Well, no. There are too many vested interests and too many salaries (note that I did not say wages) that are depending on the current system continuing – which it can’t.

What Warren’s “Economic Patriotism” does not attack. People have a rough idea what “revolution” means. They have no idea at all what “big structural change” means. I suppose if we swapped in “hope and” for “big structural” we’d have an idea of what she’s getting at.

Lambert: this is a great post but I fear you are only scratching the surface. In addition to what you cover, I would add, off the top of my head:

1. If the data were to go back to the mid-70s, you would see substantially higher numbers for firms and employees in tooling industries than in 2002. The decline since 2002 is just a fraction of the skill and talent we have lost.

2. US multinationals, real manufacturers or virtual manufacturers like Apple, are simply not interested in re-shoring. There is no convincing cost-benefit argument. You might be able to show a company that they could make boatloads of money by building a new facility in the US but they would (rightly) tell you that, if that were truly the case, they could make MORE boatloads by building it in Mexico or China. Trump can bluster all he wants but the real problem is that US manufacturing is not cost-competitive in a free-trade environment.

3. Which gets to the larger point. The great thing about manufacturing is that anyone, with training and experience, can get good at it with (enough of) the right investment in tooling, training, and experience. Adam Smith could already see 250 years ago, before there ever was big-time manufacturing, that machinery changed everything – substantially more output with substantially less skilled labor. That has been the story for the last 250 years. (John Commons wrote a great piece 100 years ago on shoemaking – search Philadelphia Cordwainers – that showed how in this industry there was a constant dance of expansion of market, new technology, deskilling, and relocation of work in search of lower cost labor. Jefferson Cowie wrote a modern version about RCA more recently but exactly the same story.)

I was at the UAW when work started moving to Mexico in a big way. There was a lot of bluster about the fact that “they” were not going to be able to do the work, and for many years there was a lot of truth to that. But with enough time and investment, of course eventually they could. (Modularization of work comes in here, too, as it is a good way to incrementally shift work to lower wage locations as skill levels grow.) I see no evidence that there aren’t many firms in China that can do technical work at the highest level, even if the “average” level of work is much lower, with wages and working conditions much lower than you could get away with in this country.

The conclusion can only be that globalization invariably leads to a race to the bottom. It has to. (Even in Germany, wages haven’t grown with productivity, because even in Germany workers have no “hand,” as George Costanza would say.) This is why I hate Dean Baker’s argument that the solution is to subject doctors and lawyers to the same degree of global competition as manufacturing workers face. It is true that costs would come down but in a further race to the bottom. It’s no solution, it’s just spreading the misery.

This is why I’m a socialist.

> globalization invariably leads to a race to the bottom. It has to.

That’s not a bug.

> I hate Dean Baker’s argument that the solution is to subject doctors and lawyers to the same degree of global competition as manufacturing workers face.

True, but the professionals might have a “come to Jesus” movement that would obviate the need to pass such a bill.

We have seen a lot of “foreign” medical ‘professionals’ in our meanderings through the American Medical Complex these last three years. An oncologist from Delhi, India, a plastic surgeon from Karachi, Pakistan, a research oncologist from Cracow, Poland, a Registered Nurse from Brazil, etc. etc. These people are working and living here in America in pursuit of the Gold Ring. (One Ring of Gold to rule them all.)

Until America institutes a National Health Service and caps medical professional salaries, nothing will change.

The main problem is structural. To mangle an infamous statement from the Vietnam War: “We had to destroy the society to save it.”

I think those who make the decisions should face the consequences of those decisions. That would be — executives. The fact that they can insulate themselves from negative consequences in the larger society is the only reason they get away with it. That, and the fact that its illegal to kill them.

I also believe the workers should control the means of production, preferrable by employee ownership and the use of credit unions.

Those professionals aren’t the problem; it’s their bosses, the elites- the donor class that are the problem. Until and unless THEY share the pain, nothing will change without revolution or money out of politics… aka revolution.

Hysteresis and path dependencies are other ways of saying systems with memory.

Systems with memories are metastable, which means they don’t have unique (or maybe even finite) sets of steady-state solutions, given the fundamental noise in the system.

In such systems, the law of large numbers is not valid.

Thus, most of orthodox economics is mathematically invalid, unless liquidity is turned up to the point that it is completely memoryless, responding only to the latest instantaneous event.

Such a system would destroy all memory bearing systems in it’s path — human beings are memory bearing systems.

The problem how I see it is that everyone was talking about how we before moved most investment from agri to manufacturing, we’d move it all from manufacturing to services.

The only problem with that is that it ignores a lot of history and worse yet, it would turn blind eye to some clear conclusions.

As in the above seemed to implicitly assume all service jobs would be better jobs than all manufacturing jobs. Which is not true, as you can’t really compare tooling engineer (to take example from above) with a hairdresser.

As with any mass change, the majority of the service jobs created woudl be low-skill, low-paid ones. They would have to be, because there just would not be enough of people with the right skills (and aptitudes).

Yes, maybe evenutally shifting to the majority of jobs to service sectors is as unavoidable as shifting majority of jobs out of agri few hundreds of years ago. But still, would not it be better (for the society and the country) to do it gradually, via automation (as part of the capital investment cycle), than just moving manufacturing offshore to the cheapest-possible?

The problem here is not with the companies.Even if they have enlightened shareholders (hahahah. The amorphous mass that are the investment funds?) who are willing to take lower returns short/medium term to do the right thing, they may get destroyed by competition who has no such qualms.

If the government is a servant of the country, and not just the few lobbyist, then this is very clearly the task of the governmnet, making sure that it works out. Well, except the problem is, if you have a few short years election cycle, no-one cares more than slightly less than the cycle, because they want to get re-elected, and you don’t get re-elected on the strength of the policies you implemented 20 years ago.

Another thing we need to acknowledge here is that while this all, in an international context, is not an entirely zero-sum game, it’s a workable approximation. Because policies that will help Americans (or Europeans or others) will often hurt elsewhere.

There’s no chance China would be now where it is w/o the massive offshoring to it. It’s pretty night impossible for a lot of low-income countries to bootstrap themselves when facing a much more developed competition, that’s just fact of life (the skills won’t develop themselves, someone has to invest into them, and that won’t happen if all you have is a poor internal market).

There can be a workable equilibrium between say the EU and the US. There cannot be a workable equilibrium between the US and the Africa (I’ll use the US and Africa as examples, put in whatever you want) w/o the US giving up some of its wealth (=some of the wealth of its people).

But tbh, this is where the wealth distribution matters (and why it doesn’t need to be a zero-sum game). If the internal US wealth distribution was different, leaving even a reasonable chunk on the table for Africa would not matter that much. It would still mean Africa was developing slower than with say Chinese-like policy (and single-midedness), but it would.

Of course then we run into a different problem. The current lifestyle of <1bln people in "first world countries" can't be really replicated across 8-9bln. But I'm getting so far away from the original problem that I'm not going to go there.

> If the government is a servant of the country, and not just the few lobbyist, then this is very clearly the task of the governmnet, making sure that it works out. Well, except the problem is, if you have a few short years election cycle, no-one cares more than slightly less than the cycle, because they want to get re-elected, and you don’t get re-elected on the strength of the policies you implemented 20 years ago.

Perhaps term-limiting the Presidency with the 22nd Amendment was a bad idea. One wonders, in any case, why the Democrats supported it, after FDR.

You do realise it may have given you three terms of Clinton, Obama? (and others)

Bush II had four terms – Bush, Bush, Obama, Obama and now he’s on his fifth! /s

Or not. One of the issues with the Democrat party is that there’s a firm line of succession (“It’s her turn”). Abolishing term limits would disrupt that; I think the number of challengers would increase because more politicians would realize they would never get to be lead dog, as it were, and change their view of the world, without staging challenges.

I would add capital controls and credit guidance to the toolbox.

> I would add capital controls and credit guidance to the toolbox.

Credit guidance?

Prof. Richard Werner (of inventing the term QE fame) among others talks about that.

Credit guidance is policy guidelines by government for banks to support lending for productive purposes rather then FIRE sector.

For example, the Asian tigers had credit guidance for decades, and some like Japan abandoned it (per Prof. Werner, he has a book about it). I think he said Germany also had and/or has credit guidance for small regional banks. Check Prof. Werner out, he has some really enlightening things to say.

I don’t know what the formal legal mechanisms are to implement credit guidance, in the US in particular. As your response indicates, it’s not even something that is heard about in the US.

> Credit guidance is policy guidelines by government for banks to support lending for productive purposes rather then FIRE sector.

The best guidance of all would be to take all the FIRE sector’s money, and then make the entire field an object of disgust and shame (as usury once was).

I enjoyed my career in manufacturing, starting with my discovery of the Western Electric Statistical Quality Control Handbook and then learning to apply statistical analysis to manufacturing processes in pharmaceuticals. Alas, the FDA still favors compliance to regulation over skilled process design, optimization and control.

Anyway, thanks for the article. The US was the primary manufacturer of machine tools at the start of 1980 and now we are ranked seventh. We have lost this basis for manufacturing and along with that, we are at risk of losing entire generations of manufacturing expertise at all levels from product development and design to finished goods output.

While my coursework in college allowed me to work in technical manufacturing you alsu point out the bias that now exists against pursuing a career in manufacturing and wonder if the selling of higher education rather than training in skilled vocations like machining has fundamentally changed how we value manufacturing?

I can remember in the 60s where there were innumerable small machine shops around Detroit servicing the aerospace community during the ramp-up to Apollo. All gone now.

If Lambert lives in the past I am a buddhist monk. There are very few with such a wide view of present times.

I think all of us live in the past, in the sense that the world as we remember it — especially fixed assumptions buried deeply in our unconscious — is at some variance with the world of today (hysteresis, i.e.).

When I became a braider mechanic in the mills many years ago, one of the ladies said to me “Now you’ll always have a job.” But that whole world is gone, now.

I’m curious as to what the growth was during the Obama years vs. the Trump years in both establishments and employment by NAICs code. Do you have a link? Your table goes from 2002 to 2018, but what about the years in between?

Based on the bls.gov data, manufacturing jobs only increased by 496K during Trump. That’s not much. In fact, the trend line is very similar to Obama’s.

Lambert, thanks for the analysis. I will note your last line,

“I’m not sure that’s meaningful absent an actual industrial policy, democratically arrived at, and a mobilized population (which is what the Green New Deal ought to do).”

That is exactly what my Green New Deal Plan is designed to do. My mentor was the late Professor Seymour Melman, who was one of the world’s top experts on the machine tool industry, and who warned as far back as 1988 in a book called ‘the demilitarized society’ that the U.S. was at the ‘point of no return’ exactly because the industrial machinery industries were in such bad shape. In fact, he felt that it was not possible for these industries to regenerate by themselves, thus the point of no return, so they needed help from the government to revive, and there needed to be large scale importing of engineering talent from what I would call more advanced countries to ‘train the natives’, as he put it (not sure if that is pc at this point). (If anyone is interested, I posted a description of Seymour’s work at NakedCapitalism, )

Tim Cook’s comments have been chilling because he is pointing out the systemic nature of a manufacturing base, like a forest if it gets too small, the whole thing effectively collapses. At this point, it seems to me, the U.S. can only ‘bring back manufacturing’ by engaging in huge public works projects, require domestic content, and help companies produce the associated parts and equipment. It would be especially important to require, after a few years, that the machinery be produced in the U.S. This is the sort of thing the Chinese do in their sleep, but most of the elite have been living in Reagan’s brain for so long they forgot they can use the Federal government for nation building. I tried to counter some of the myths of manufacturing, as I put it, in my book “Manufacturing Green Prosperity”

What do you do when the finance-types in control of all these firms say, “No thanks”? Tim Cook complains that the skill base isn’t here – which by now it might not be – but the real driver is lower labor costs elsewhere. Guaranteed profits like in the MIC?

Left in Wisconsin, thanks for replying. I think you need a form of national planning. not gosplan type, more like in the one to two trillion per year range, that the Feds directly spend — I would advocate on a green new deal plan, for instance. That’s not exactly guaranteed profits a la MIC, and a friend doesn’t want me to use the word ‘infrastructure industrial complex’, but I think the Chinese did something rather similar, they planned the building of vast public works, and they knew that would provide a huge market for manufacturing firms. i think this sort of dynamic helped before in american history, think of encouraging rail in the 19th century or the public works in the new deal. i wrote about this in American Prospect. If you have ‘domestic content’ laws for all the parts being used for the public works, then you don’t have to worry about lower wages overseas. It’s absolutely necessary that the Green New Deal people put that in their language, I don’t know if they will

Is “domestic content” still legal under WTO? Just trying to figure out how far from here to there. I have huge respect for Melman.

My understanding is that GATT allowed for domestic content if it was for ‘general infrastructure’. Don’t know about WTO, but it may be the same, I remember having a conversation with someone about this in 2008…so maybe it is WTO. Judging by what Trump is getting away with, maybe all you have to do is declare something a matter of ‘national security’….but frankly I don’t know. What the US, during Obama’s administration, did to India, which was trying to use domestic content to build their solar industry, is unconscienable (sp)…then India sued back when several US states tried to do the same thing. Clearly if there was support for a green new deal, there would be support enough to tell the WTO to go to hell, or what would probably happen, the WTO rules would change with enough pressure

Basically heavy infrastructure is industrial policy. Though the U.S. needs Canada to fill in the holes even compared to 1950.

> the systemic nature of a manufacturing base, like a forest if it gets too small, the whole thing effectively collapses

Good metaphor. Or what used to be a single range for a species like the wolves gets split by development, and the resulting two ranges are each too small to support a wolf. One solution is to build a “highway” between the two ranges, but that’s obviously a kludge (rather like a fish ladder). One gets the impression that minor repairs — like Warren’s? — are like those highways, or fish ladders. What is needed is to restore the range, in its entirety,

Sorry, but manufacturing has been in recession this year Lambert. Be aware the tied of revisions. From a pratical pov, Obama or Trump doesn’t matter. But due to massive junk bond allocations and imo exhausted heavy manufacturing companies, they are in trouble going forward.

China itself is overrated right now as well. This board lives in denial on this issue.

> Sorry, but manufacturing has been in recession this year Lambert

A manufacturing Renaissance would not abolish the business cycle, as I point out in the post. Consider reading it.

Manufacturing shouldn’t be done in places with strong patent laws and strong, strict legal system. This is too high legal risk. Just a lawsuit can shut down the entire production line, or a factory. You don’t have such risks in China, India etc.

Also in a country with strict patent laws you can’t produce a lot of product that are legal in countries with lax patent laws. Like a product fulfilling India’s patent laws but not US patent laws. You can produce such product in India and sell domestically, but you can’t manufacture it in the US and export to India, because of US patent laws being stricter than India’s.

But the opposite is possible – you can manufacture everything for every market in a country with little or patent protection, just be careful where you export it, eg. export products with full US patent licensing to US, while export cheaper products, with less patent licensing to places like Africa etc.

> Manufacturing shouldn’t be done in places with strong patent laws and strong, strict legal system. This is too high legal risk.

This is silly. Mentioned in the post, besides tooling, are textiles, apparel, and pulp and paper. In each case, the issue is the skills of the workforce, skills that are not subject to IP. By your theory, wood containers/pallets, which has not been destroyed, would have preserved itself through patent protection. IP for pallets? Really?

We’ve been tearing down our ability to manufacture for 40 years. When I last worked in a factory nearly that long ago, it was obvious we had a shortage of people who could do machining and tooling (I got pressed into doing both, which should tell anyone who knows me just how bad things already were.) and so were facing a big problem with keeping the plants up to modern standards. Now the equipment that used to be at Goldendale Aluminum and Geneva Steel is in China. Gee, who saw that one coming?