By Yasmine Bekkouche, Postdoctoral researcher, ECARES and Julia Cagé, Assistant Professor in Economics, Sciences Po; CEPR Research Fellow. Originally published at VoxEU.

There is growing concern that money has corrupted politics. The column uses data from French elections since 1993 to show that an increase in spending per voter has consistently increased a candidate’s vote share. Caps on spending may increase this impact, as marginal effects are large. The price of a vote varies widely, and is most expensive for the extreme right.

Seven of the Democratic candidates for the 2020 US presidential election have pledged to prioritise campaign finance reform in their first bill. This unprecedented development reflects a growing concern that money has corrupted politics. Existing research on the influence of campaign spending on elections has conflicting conclusions, however. For example, Kalla and Broockman (2018) performed a meta-analysis of a large number of field experiments in the US and concluded that there was no effect from campaign contact and advertising on the choice of candidates in general elections.

In contrast, our new dataset of all French municipal and legislative elections between 1993 and 2014 shows that an increase in spending per voter consistently increases a candidate’s vote share (Bekkouche and Cagé 2018). France is an important example. Like many countries including Belgium, Brazil, Canada, and the UK – but unlike the US – it has limited campaign spending by law.

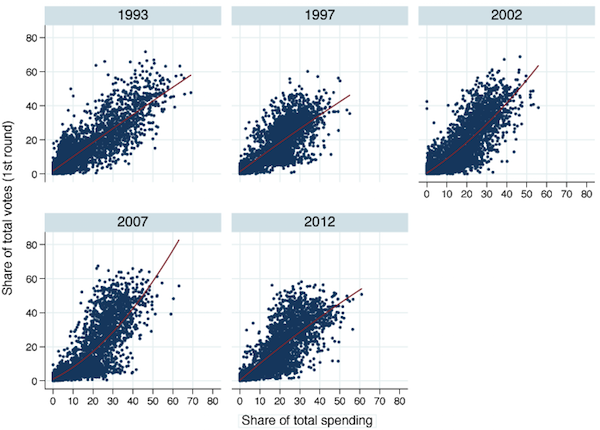

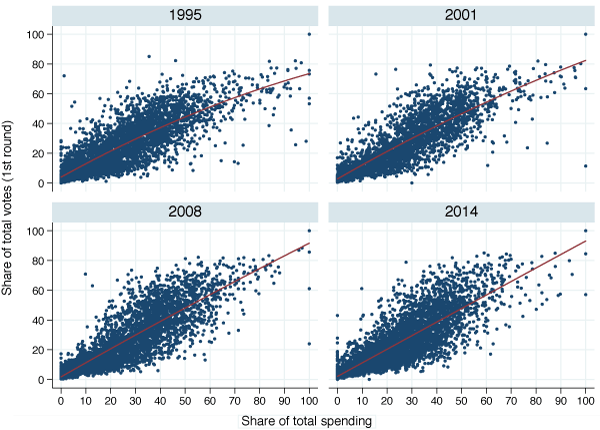

The database covers four municipal elections (1995, 2001, 2008, and 2014) and five legislative elections (1993, 1997, 2002, 2007, and 2012), as well as campaign spending and votes for approximately 40,000 candidates. It shows that, for French legislative (Figure 1) and municipal (Figure 2) elections, there is a strong correlation between a candidate’s percentage of the first-round vote and her share of total election spending in the electoral district (each point represents a candidate). In general, the greater the amount by which a candidate outspends other candidates, the higher that candidate’s share of the first-round vote.

Figure 1 Relationship between the proportions of total spending and total vote share, legislative elections in France, 1993-2012

Source: Bekkouche and Cagé (2018).

Figure 2 Relationship between the proportions of total spending and total vote share, municipal elections in France, 1995-2014

Source: Bekkouche and Cagé (2018).

Correlation or Causality?

Many other factors may be involved. For instance, a promising candidate might raise more donations (money goes to money, and therefore to winners) and also more votes because of her popularity, not because her spending has brought in more votes.

We used exogenous variations on the revenues of candidates to identify the causal effect of spending – that is, variations determined by factors external to the district or candidate. The two instruments we built rely on the fact that candidates are affected by regulation on campaign funding differently, depending on the source of funding they are most dependent on.

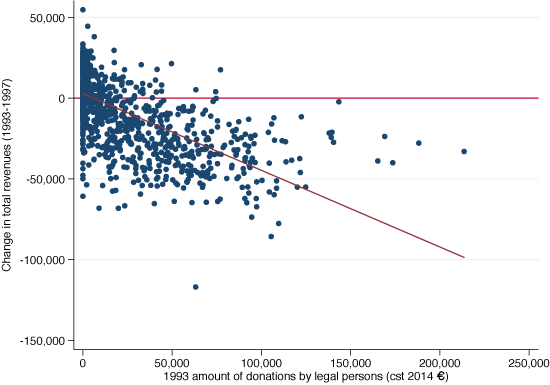

We considered the exogenous variations resulting from a new legislation in legislative elections that prohibited corporate donations to election campaigns in 1995. This law was enforced for the first time in the 1997 legislative elections, and affected only candidates who previously relied on private donations from legal entities. In other words, sudden and unexpected reform led to a considerable fall in the resources available to some candidates but not others, even in geographical areas with the same characteristics and inside the same party. It was therefore a near-perfect natural experiment.

Focusing on the candidates who ran in both the 1993 and 1997 elections, we could instrument the change in spending between 1993 and 1997 by the amount of donations received in 1993 from corporations.

Figure 3 illustrates that candidates who relied strongly on corporate donations were not able to recover from the ban. On average, an additional euro received from corporations in 1993 is associated with a €0.6 decrease in total revenues between 1993 and 1997.

Figure 3 Change in total revenues for candidates in French legislative elections between 1993 and 1997, depending on the donations from legal entities received in 1993

Source: Bekkouche and Cagé (2018).

According to our estimates, the price of a vote in France is only a few tens of euros. Hence, despite existing ceilings on election expenses and capped private donations, money plays an important role in French politics, sometimes even a decisive one as far as elections are concerned.

Despite Spending Caps, or Because of Them?

While the existing literature obtains conflicting results regarding the impact of campaign expenditures on votes, this may be because research has mostly focused on the US, where campaign spending is not capped. Given that candidates’ expenditures keep growing in US elections, decreasing returns of spending may dominate – what is the value of spending an additional $1 on television advertising when you have spent more than $1 million?

In a country like France, where spending is limited, the marginal returns of campaign spending may be large. This does not mean that money matters less in places with no regulation. The absence of campaign finance limits in the US adversely affects electoral competition, because candidates mostly need to be wealthy to run. In other words, marginal effects may be small, but average effects are large.

This means that, even in a country such as France, money plays an important role in politics, and that regulation ought to be tightened. According to our estimates, the effects are strong enough to explain the left’s victory in the 1997 general election.

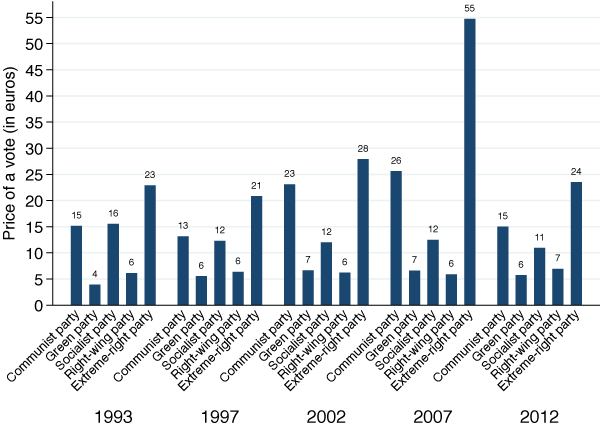

Variable Pricing for Votes

The price of a vote varies, depending on elections and political parties. In particular, spending by far-right candidates has much lower returns than spending by other parties. Figure 4 shows that the price of a vote is around €6 for legislative elections for the right-wing party and for the Green Party, and is stable through time. The price is slightly higher for the Socialist Party (it varies between €11 and €16 depending on the electoral year) and for the Communist Party, with no variation over time. Lastly, the price of a vote is much higher for the party of the extreme right than for others.

Figure 4 Legislative elections: Estimation of the price of a vote, depending on the time period and on the political party

Source: Bekkouche and Cagé (2018).

Why Is Campaign Spending Less Efficient For The Far-Right Than For The Other Political Parties?

Extreme-right candidates may be less effective campaigners. This would be the case if these candidates suffered from a valence disadvantage (disadvantaged candidates may choose more extremist positions). Anecdotal evidence suggests that the extreme-right party in France has difficulties fielding quality candidates across the country for legislative elections.

It may be linked to the salience of the issues on which the extreme right campaigns, such as opposition to mass migration. The immigration stance of the Front National (now called Rassemblement National) is the toughest in France. As this controversial position is well-known, campaign spending may not affect the voters’ knowledge of a candidate’s position. On the other hand, voters may be unaware of, or misperceive, Green Party candidate positions on issues such as the development of local currencies (which are not a priority issue for voters). Therefore campaign spending by Green Party candidates can make people aware of these issues and change their vote.

Far-right voters may also be more ideological, and so vote for extreme-right candidates regardless of their characteristics. Therefore, they may also be less responsive to campaigns.

Using data on parliamentary elections in Finland, Kestilä-Kekkonen and Söderlund (2014) have shown that the characteristics of the party leader are a much stronger predictor of the far-right vote than district-level candidate characteristics. And Le Pennec-Caldichoury and Vertier (2019) show that, in the first round of the 1993 French legislative elections, political manifestos of extreme-right candidates tended to be similar (all following the same national model), while the manifestos of other parties’ local candidates varied widely.

In recent years, far-right political parties have made gains in elections in many countries. Our results shed light on the mechanisms that drive their electoral success.

On first reading (I had more success reading bottom to top from the conclusion to the intro, it’s kinda wonky) I find this to be interesting data, and can make two observations. Firstly,

“Figure 3 illustrates that candidates who relied strongly on corporate donations were not able to recover from the ban. On average, an additional euro received from corporations in 1993 is associated with a €0.6 decrease in total revenues between 1993 and 1997.”

This passage shows that the dem party would likely be blown up by finance reform

.

Secondly, and in more of an “I have a feeling” kind of way, The US has two extreme right parties, and campaign finance as it is will keep it that way, with voices such as bernies given a marginal voice in one half of the duopoly and being effectively shunted off to the siding, he’s at the station but the train that’s given the main track is the corporate wing of the party. A good real life example is the AOC hate from both main stream wings of both parties. And how does one factor in the MSM here? What’s the value of the msm’s unhindered right wingery? I don’t know enough about France to make a judgement on that, but the elite in the US has an iron grip on the process and a jenga like control over the structure in an “if you take that piece out the whole thing will fall down” seen in the reaction to student loan forgiveness as well as in the response to the GFC in allowing those who trashed the economy to rebuild it in their own right wing image where they saved the rich and told everyone else that if they pulled hard enough on their shoes they would reach heaven, which in the US is Wall Street.

A little bit of context may be helpful here.

French election laws are extremely strict about expenditure, and candidates have to present accounts at the end of campaigns, which are then certified by an independent Commission. Income from various sources is subject to individual rules and limits, and violations are severely punished – Sarkozy was prosecuted for cheating in the 2012 Presidential campaign, by claiming that expenditure on his personal campaign was actually expenditure on the campaign of his party. The upshot is that the total amount of money spent on elections is very small: less than €200M for the presidential and parliamentary campaigns of 2017, for example, of which about a third came from public funds. So instinctively it seems hard to believe that differences in spending can have much effect when the law guarantees, for example, equal TV time and equal space for election posters, and when most of the money goes on election meetings, organisation and publicity. Local issues and loyalties can also be very important. I suspect the answer lies elsewhere.

The authors have chosen to focus on votes gained in the first round of elections, where, traditionally, the electorate votes for their candidate of genuine choice, before voting tactically in the second round. That’s an understandable approach, but may now be a bit dated. Since the shock of Jean-Marie Le Pen getting into the second round against Chirac in 2002, much of the establishment’s time has been spent arguing that, above all, voters of all persuasions should “form a barrier” against the National Front/Rassemblement National. More and more, people have found themselves pressured into voting even in the first round to ensure that the RN does not make it into the second. The last election saw a great deal of tactical voting in the first round as well. Many people voted for Macron as a safe bet, and to keep the unlovely François Fillon out of the second round.As a result, Macron made it into the second round against Le Pen, where he was certain to win. A bit less tactical voting, and Macron might not have made it past the first round.

Macron’s name reminds, us, of course, that election spending by candidates is only a small part of the picture. Media coverage of elections is heavily biased towards establishment parties, as you might expect, and in many cases unashamedly partisan, especially for candidates of the established Right. In 2012, journalists at the right-wing Le Figaro actually protested publicly at being turned into propagandists for Sarkozy. This means that outlying parties are heavily disadvantaged and the money they spend is relatively less valuable. This particularly applies to the NF/RN, which was subjected to a hysterical series of attacks in the media in 2017, calculated to make anyone feel guilty even for thinking of voting for them. Le Pen and the RN would have lost anyway, but it’s fairly clear that the margin of defeat would have been smaller (and so the effectiveness of campaign spending correspondingly greater) had it not been for the united and vocal opposition of the almost the whole of the media, the political class, and the intellectual world of which the authors are part.

Paraphrasing the Bob Hope movie:

Don’t call me “Bwahaha”

https://www.zerohedge.com/political/its-been-grim-kamala-harris-debate-performance-fails-impress-major-donors

Looks like canned lines and stage laughter no longer equal open wallets.