By Taneli Mäkinen, Advisor, DG for Economics, Statistics and Research, Bank of Italy, Lucio Sarno, Professor of Finance, Cass Business School, City, University of London, and Gabriele Zinna, Advisor, DG for Economics, Statistics and Research, Bank of Italy. Originally published at VoxEU

During the recent financial crises, government helped reduce the funding costs of banks by providing them with insurance, thus curbing panic in banking systems and financial markets. This column argues, however, that these beneficial effects can be attenuated when guarantees are risky in the sense that they offer weaker protection in recessions, when the guarantor is more vulnerable, or the guarantees are less certain. Using a large international panel of banks, a significant risk premium is found to be associated with implicit government guarantees.

As the recent financial crisis entered a far more virulent phase around the time of Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy in late September 2008, governments made extensive use of bank bailouts, both collective and individual; some guarantees were explicit, others were implicit; some financial institutions were bailed out, others were not (Panetta et al. 2009). Bank bailouts helped reduce the tail risk of financial institutions, making them safer, and helped curb the turmoil in financial markets; thus, in safe-haven countries such as the US, government guarantees generated beneficial effects for banks and helped reduce bank funding costs (Gandhi and Lustig 2015).

At the same time, those policies may have contributed to increase banks’ exposures to aggregate risk, especially in most vulnerable countries. First, government support hindered the fiscal capacity of some sovereigns, and the resulting sovereign fragility, in turn, fed back to the banks that were more likely to receive stronger support from their governments (Acharya et al. 2014, Correa et al. 2014). Second, guarantees may have made banks exposed to policy uncertainty, a source of non-diversifiable risk, as bank idiosyncratic risk decreases with the too-big-to-fail status (Acharya et al. 2016). This evidence, taken together, suggests that banks are not equally exposed to the risks affecting their guarantor, and therefore to aggregate risk.

When Government Guarantees Are Risky

In a recent paper by (Makinen et al. 2019), we develop a simple framework to describe the risk-return trade-off that government guarantees can generate in bank asset returns. In our setting, government guarantees are risky in the sense that they provide protection that depends on the aggregate state of the economy. In recessions, governments are arguably more willing to rescue banks; however, weaker public finances may constrain their ability to support them. If the implicit support offers higher protection in good than in bad states of the world, it can make the payoffs of debt and equity claims more positively correlated with the aggregate state of the economy. As a consequence, bank asset risk premia would increase, dampening the reduction in bank funding costs and thus attenuating the beneficial effects of bank guarantees. This simple theory also predicts that such effects should be more prominent for banks that are guaranteed by riskier sovereigns. These direct effects of the guarantee arise even separately from the standard indirect effects operating through risk-taking.

Is the Riskiness of the Guarantee Priced in Bank Asset Returns?

We test this theory by examining its predictions on the direct effects of implicit guarantees using data for a reasonably large cross-section of banks, covering 15 developed countries, over the 2004-2018 sample period. To isolate the direct effects of the guarantee, we double-sort banks first by bank risk and then by a measure of expected government support (EGS), namely, the deposit-to-GDP ratio, which proxies for the bank market share of deposits. That is, differently from the too-big-to-fail literature, our focus is on the importance of the guaranteed banks for the national economy rather than on their systemic importance at the global level.

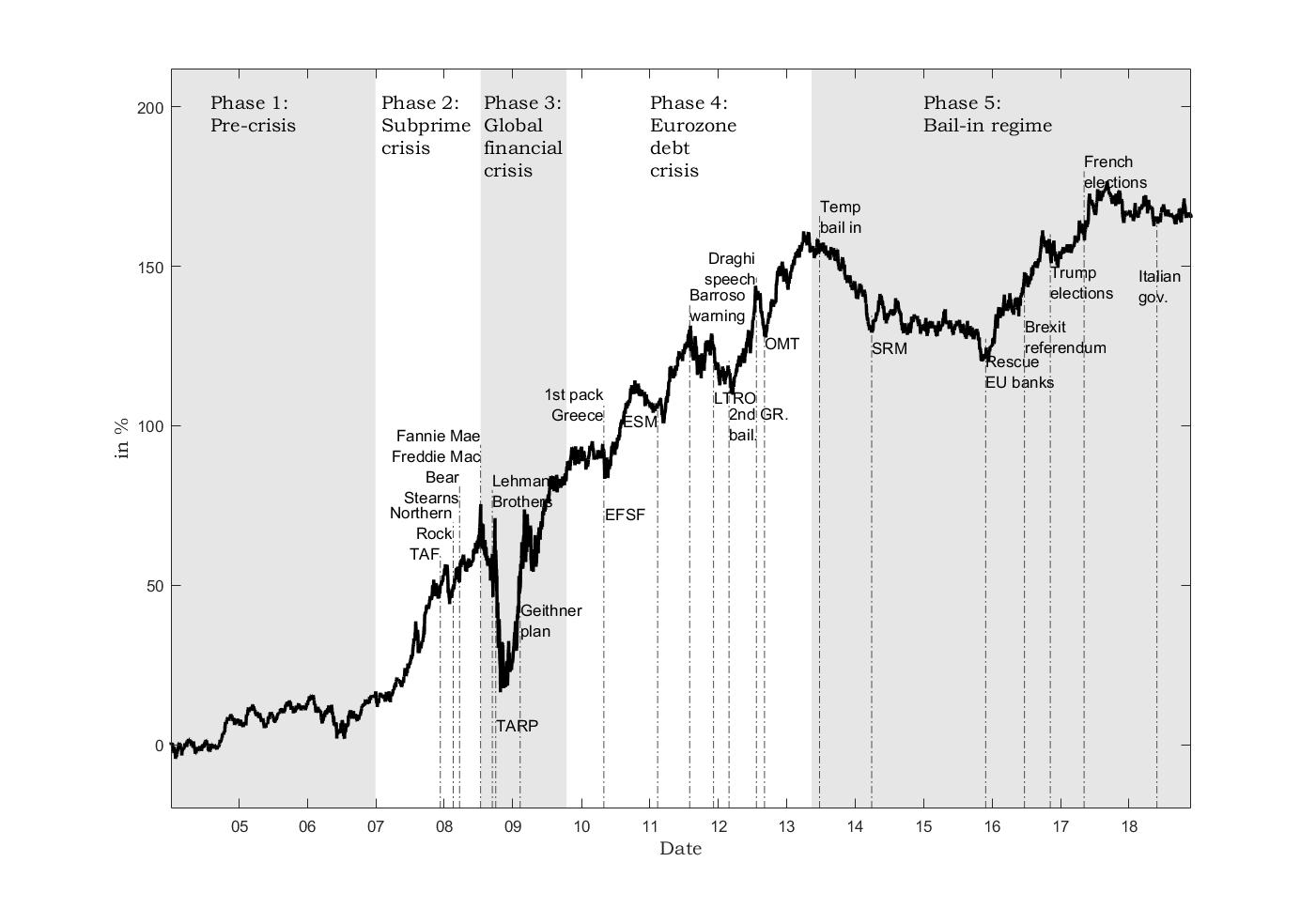

The empirical results suggest that the spread in equity returns between high deposit-to-GDP portfolios of banks and low deposit-to-GDP portfolios of banks is very large, as it can amount to as much as 11% per annum. This begs the question: What drives this excess return? Based on a set of standard risk factors, equity spread portfolio returns cannot be explained – that is, there is a puzzle in bank equity returns. However, there appears to be an EGS return factor which can explain the risk-return trade-off. Figure 1 shows that its evolution is characterised by five distinct phases, and its main turning points are associated with key policy events that took place during the sample.

Figure 1 The (cumulative) EGS return factor

Using the EGS factor, the equity risk premium associated with the government guarantee is quantified to be in the range of 5%-9% per annum, across equity spread portfolios. More fundamentally, an EGS premium appears to exist only when banks can be bailed out, and sovereign risk is non-negligible. In fact, this premium does not exist for the sample of banks located in safe-haven countries (Japan, the US, Germany, and Switzerland). Our analysis also reveals that this premium is substantially higher when we exclude the period following the adoption of the bail-in regime by EU members. Under the bail-in regime, bondholders and/or depositors, rather than taxpayers, are forced to bear the burden of bank recapitalisations. Intuitively, under a fully operational bail-in regulation, the key mechanism behind the EGS risk premium should either no longer be at play or be far less prominent.

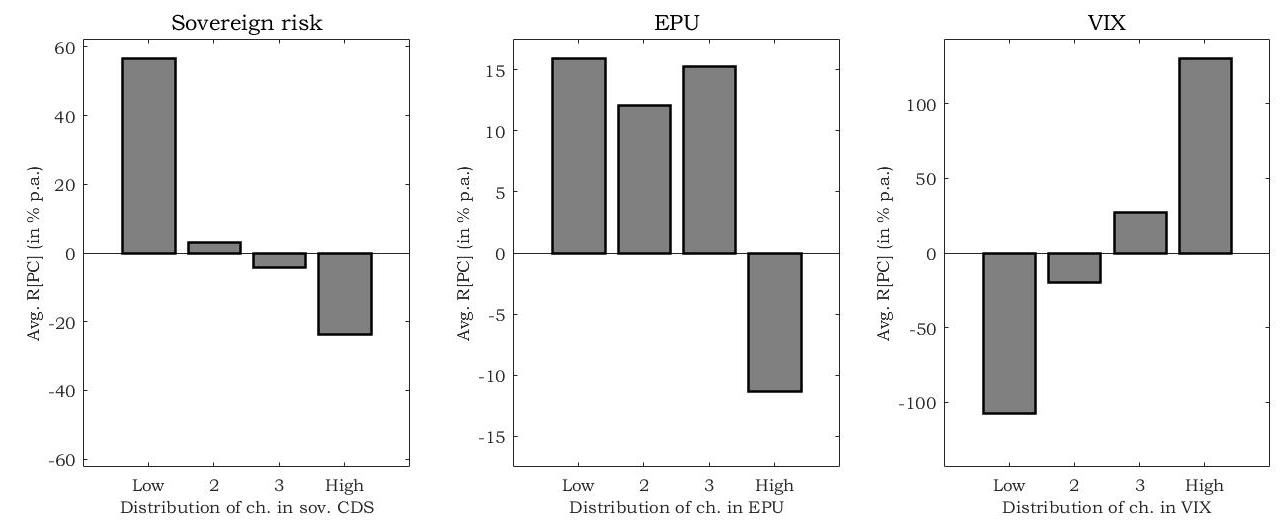

Figure 2 The EGS factor, sovereign risk, EPU, and VIX

Figure 2 illustrates that the EGS return factor drops when sovereign risk increases and vice versa, confirming that sovereign risk is an important determinant of the EGS factor. The factor also drops when US economic policy uncertainty increases. In contrast, high EGS banks are less exposed to tail risk than low EGS banks given that the factor co-moves positively with innovations to the VIX index. Thus, although government guarantees offer protection from tail risk, they expose banks to sovereign risk and policy uncertainty.

Conclusions and Policy Implications

The analysis presented here suggests that the risk profiles of government guarantees ultimately determines the extent to which they reduce bank funding costs, given that they not only reflect the actual probability of default of the bank but also include a risk premium component. Such a premium is likely to be low, making the guarantee more effective, when the riskiness of the guarantor and the uncertainty associated with the guarantee are low.

These findings can potentially help inform the design of bank guarantees, contributing to the ongoing debate on the bank-sovereign nexus. In particular, the evidence in our paper shows that the EGS premium is essentially zero since the adoption of the bail-in regulation in the EU. This finding lends support to the view that reforms of this kind, to the extent that are credible, reduce investors’ expectations of government support for banks, thereby weakening the link between sovereigns and banks.

Relatedly, the recent slowdown of the global economy, against the backdrop of persistently high levels of public debt, has revived concerns related to sovereign risk, especially in some European countries (ECB 2019). At the same time, the incompleteness of the EU banking union has received renewed attention (Hall 2019). The results uncovered in the study contribute to this debate by highlighting that uncertain guarantees, especially when provided by vulnerable sovereigns, are significantly less effective.

See original post for references

I guess I belong to one of those countries mentioned above in which rescuing the TBTF results in sovereign increased risks and I would welcome anything that reduces such EGS return factor but I would welcome even more that any TBTF bail out comes with more stringent conditions –even nationalization of the entity– and proper treatment of the managers. The moral hazard issue is more important when sovereign debt is at risk. Moreover I think that in the case of eurozone members lacking sovereignity on their currency the monetary authority should share responsibility for their regulatory failures.

There’s really only one side to the story because the banks referred to as ‘sovereign’ aren’t. So they are pushed and pulled by economies they cannot control. That they are expected to support their own ‘sovereign’ banking systems is an oxymoron. The bail-ins in the EU haven’t been getting much exposure lately – did they stop doing that because it was so politically disastrous? Or was it just tokenism to offset Draghi’s “whatever it takes” largesse. And that largesse was also not largesse; it was the only thing that worked. And they really lost me when they referred to the “incompleteness of the EU banking union”. What banking union? A decentralized pact to support local banks and cut back on social spending? I hardly call that a banking union – as this study proves. That whole EU effort is just more roller-boarding down a spiral; self sacrifice to protect the value of the euro. For what? Or, for whom?

Under the bail-in regime, bondholders and/or depositors, rather than taxpayers, are forced to bear the burden of bank recapitalisations.

Bondholders should, of course, bear the risk of bank failure.

Otoh, depositors have no other choice* than to use one bank, credit union, or other inherently-risky private depository institution since only depository institutions may have inherently risk-free accounts at the Central Bank itself – not the non-bank private sector.

So depositors should have the option of inherently risk-free debit/checking accounts at the Central Bank itself before any thought is given to have them bail-in banks and other depository institutions.

But wouldn’t interest rates rise if banks had to honestly borrow rather than have captive depositors?

Not necessarily since the following should lower interest rates:

1) Equal fiat distributions to all citizens into their accounts at the Central Bank for lending, if desired, to banks and other depository institutions. This should replace all other fiat creation beyond that created by deficit spending – as a natural matter of equal protection under the law.

2) Negative interest to be levied on large and non-individual citizen accounts at the Central Bank. This is only natural too since the MOST inherently risk-free deposits at the Central Bank should return is ZERO** percent and that only for individual citizens up to a reasonable account limit – as a natural right of citizenship. Moreover, the negative interest collected could be used to fund, at least partially, the Citizen’s Dividend mentioned in 1).

*Except for mere physical fiat, paper notes and coins, which hardly counts as a choice, since, for example, physical fiat is useless for electronic commerce. Imagine also if payrolls, especially of large companies, were paid with physical fiat.

**in order to avoid welfare proportional to account balance.