Yves here. The authors of this study get points for finding a natural experiment on privatizing Medicaid, namely Texas starting in 2007. Although the findings and detail are valuable, I have doubts about the way they framed one of their conclusions. One reason privatized Medicaid delivered better results in Texas than the old government-run version is that Texas had a punitive limit on prescriptions of three meds a month. That limit was removed when Medicare was made private.

Texas could just as easily have lifted that restriction on its own without privatizing Medicare, so it isn’t clear that the benefits of that change should be attributed to privatization. It’s analogous to the false claim regularly bandied about by the press and even supposed bank experts, that big banks are more efficient. That’s not true once you pass a pretty low size threshold. But that’s the excuse for tons of bank mergers, when the real reason is the people running bigger and more complicated banks get paid more.

True, the merged bank goes through headcount cutting, but the canard is the merger made that possible or necessary. In fact, the cost data shows the two old banks could have created the same efficiencies on their own. but it’s easier to clean house after a big deal.

By Timothy J. Layton, Assistant Professor of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Nicole Maestas, Associate Professor of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Daniel Prinz, PhD Student, Harvard University and Boris Vabson Seidman Fellow and Associate, Harvard Medical School. Originally published at VoxEU

There is much debate, and nowhere more than in the US, about whether public services such as healthcare should be provided by private companies, which may offer greater efficiencies but which are more susceptible to moral hazard and adverse selection of consumers. This column uses evidence from a provision change in Texas to show that contracting healthcare provision out to private companies increased the level of care patients received, but increased overall costs for the government.

Whether public services should be provided directly by the government or contracted out to private firms is a central debate in public finance and public policy around the world. Private provision of public services is common in education, healthcare, defence, and, in the US, even in incarceration. In other areas – including social security, disability insurance, and infrastructure development – governments have considered private provision as a possible way to improve efficiency. As the US and other developed countries grapple with the rising complexity and costs of healthcare, the debate over whether healthcare services and health insurance programmes are more efficiently provided by the government or by competing private firms has become a crucial question.

Proponents of the private provision of social insurance argue that the competition of private plans will produce better outcomes. The competing plans are incentivised to keep costs low and ration care efficiently because they get to keep savings and because they want to attract enrolees. There is empirical evidence that these arguments can have merit in some contexts (Newhouse and McGuire 2014, Dranove et al. 2017, Curto et al. 2019). Opponents of the private provision of social insurance argue that competition may not be strong enough and regulation may be too lax, leading to potentially more expensive and lower quality care. Further, there are concerns that adverse selection can incentivise private plans to inefficiently design contracts or engage in other efforts to keep costly enrolees away. There is empirical evidence that these concerns should be taken seriously (Curto et al. 2014, Duggan et al. 2016, Cabral et al. 2018, Duggan and Hayford 2013, Aizer et al. 2007, Geruso and Layton 2017, Kuziemko et al. 2018).

In a recent paper (Layton et al. 2019), we show that the effects of private provision of social insurance may be more complex than either side would suggest. We examine the shift from public to private provision of Medicaid (the US programme for providing health insurance to low-income and disabled Americans) to low-income disabled beneficiaries in Texas and find that private provision led to higher costs to the government but at the same time improved healthcare for beneficiaries.

Within the US healthcare system, Medicaid is the setting where the question of private vs. public provision of health insurance is most policy relevant. Over 43 million Medicaid beneficiaries receive their health insurance benefits from a private health plan, with $162 billion paid to these plans each year (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2016). Our focus on the disabled Medicaid population is also important. In 2014, Medicaid spending for this population amounted to almost $187 billion or 40% of total Medicaid spending, even though individuals with disabilities make up only 13.5% of total Medicaid enrolment (Kaiser Family Foundation 2014a,b). While most states have already shifted healthier Medicaid populations to private plans, the transition of individuals with disabilities to private plans is either recent, ongoing, or currently under consideration. Despite this, we know relatively little about the effects of private provision on this population.

In 2007, Texas moved disabled Medicaid beneficiaries from a public fee-for-service plan to private managed care plans. This reform was implemented in only a subset of counties, and our research compares the counties where beneficiaries were put into private plans to neighbouring counties where they stayed in the public plan.

We find clear evidence that private plans rationed healthcare services to a lesser degree than the public Medicaid programme. Specifically, we show that private provision led to 30% higher spending on prescription drugs (Figure 1a). This increase came from drug categories that are generally considered valuable for treating chronic conditions that are common in the low-income disabled population that we study, such as insulin, antipsychotics, anti-depressants, statins, and asthma and pain medications.

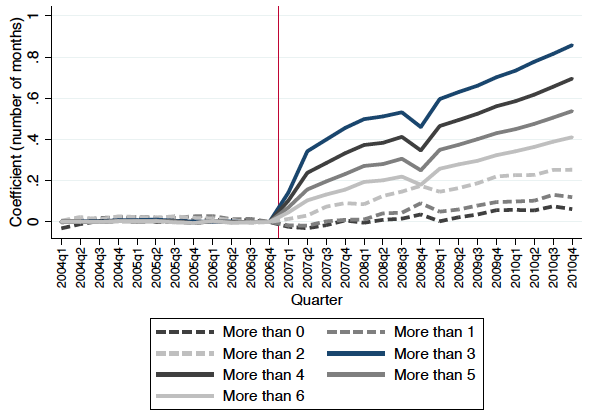

What might explain this large increase in prescription drug consumption after privatisation? We think that it is a consequence of institutional features of the public Medicaid programme in Texas. Beneficiaries in Texas’s public Medicaid programme have a three-drug cap on the number of drugs they can use in a month. We show that the removal of this cap under the privately managed care plans explains most of the increase in prescription drug spending. The number of months when people use more than 3 drugs increased significantly while the number of months when people use more than 0, 1, or 2 drugs increases only slightly (Figure 1b), suggesting that the cap in the public plan was binding for a substantial number of beneficiaries.

Figure 1 The impact of Medicaid privatisation on prescription drug spending

(a) Prescription drug spending increased

(b) The three-drug cap was binding

Notes: Figure shows the impact of Medicaid privatisation on prescription drug spending. Panel (a) shows the difference between privatisation and non-privatisation counties in log prescription drug spending. Panel (b) shows the difference between privatisation and non-privatisation counties in the number of months that a beneficiary has more than 0, 1, …, 6 unique prescriptions.

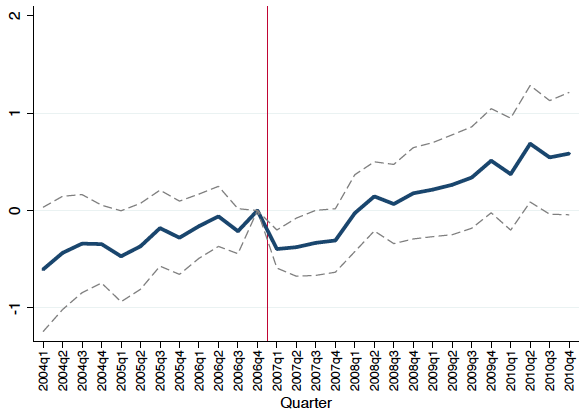

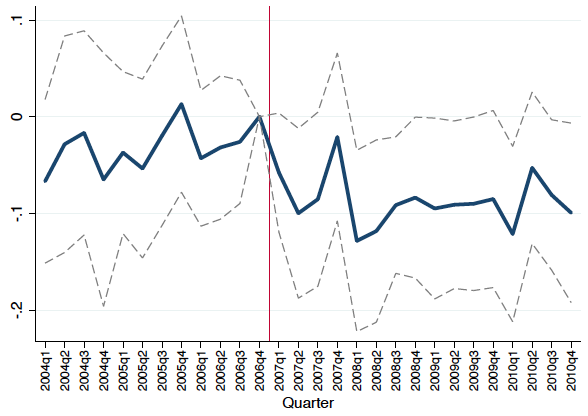

Privatisation also led to an increase in outpatient spending (Figure 2a). This increase resulted from a combination of 8% higher unit prices paid by private insurance companies to healthcare providers and an 8% increase in the quantity of services provided. In fact, the increased quantity of outpatient services utilisation could have come partly as a direct result of higher unit prices to providers, as these could have led to increased care access. In addition, we document a decrease in inpatient spending of at least 8% (Figure 2b). We further show that this decrease was concentrated among inpatient stays for conditions treated by the same drugs that beneficiaries got better access to post-privatisation. Taken together, these results suggest that the decreased inpatient spending could be indicative of improvements in care quality, as these could reflect reductions in avoidable hospitalisations through greater use of chronic disease-related drugs.

Figure 2 The impact of Medicaid privatisation on outpatient use and inpatient spending

(a) Number of outpatient days increased

(b) Log inpatient spending decreased

Notes: Figure shows the impact of Medicaid privatisation on outpatient utilisation and inpatient spending. Panel (a) shows the difference between privatisation and non-privatisation counties in the number of outpatient days. Panel (b) shows the difference between privatisation and non-privatisation counties in log inpatient spending.

This improvement in care quality came at a price for the government, however. Total spending was 12% higher under private provision. We show that this spending increase came through Texas paying private plans more than it would have paid out in counterfactual fee-for-service payments under public provision. Importantly however, we find that the vast majority (80%) of this spending increase in Texas was passed-through to providers and beneficiaries, in the form of additional healthcare services and higher provider reimbursement rates. Overall, our results suggest that the privatisation of social insurance programmes has more nuanced effects than previously recognised, and therefore warrants more nuanced policy debate. Our findings suggest that private provision does not always reduce costs or reduce quality.

Instead, its effect is dependent on the specific context and private coverage design, and ultimately involves cost-quality trade-offs. Indeed, our results suggest that when public programmes are stingy and exhibit extreme forms of rationing (as in Texas’s three drugs per month cap), privatisation can improve outcomes for beneficiaries, albeit at the cost of higher spending. We believe this can occur due to a complex political economy problem – conservative state legislators only agree to higher programme spending if the programme is privatised, under the assumption that both marginal and inframarginal dollars will be spent more efficiently under private provision. This suggests that the effects of privatisation may vary substantially, depending not only on the design of the privatised programme but also on the design of the public programme that the privatised programme is replacing.

Authors’ note: We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, the Social Security Administration through grant #5 DRC12000002-06 to the National Bureau of Economic Research as part of the SSA Disability Research Consortium, the National Institute on Aging (P30-AG012810), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K01-HS25786-01). The findings and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA, any agency of the Federal Government, or the National Bureau of Economic Research.

See original post for references

For the real story see the Dallas Morning News report on the abysmal behavior of the for-profit corporations:

https://interactives.dallasnews.com/2018/pain-and-profit/

This series won the Bingham prize at the Nieman Center at Harvard

https://nieman.harvard.edu/news/2019/04/pain-and-profit-by-the-dallas-morning-news-wins-worth-bingham-prize-for-investigative-journalism/

A brief glimpse: “…health care companies in the state made billions of dollars while denying or stalling crucial taxpayer-funded medications and treatments to thousands of sick children and disabled Texans. Those actions caused significant and needless suffering.”

Privatization of state Medicaid is a new cruelty to vulnerable populations whose effects are hidden from view by the HIPPA law and the innate difficulty of the disabled to organize. Academics hired by state agencies for policy studies are incentivized to praise the system, furthermore, they are granted exclusive access to cases and can cherry pick examples of successes and ignore the failures – if they were ever truthfully documented by providers. That the DMN was ever able to find and interview patients is a testament to their reporters’ perseverance and dedication to good journalism.

I deal with the absurdities and cruelties of Virginia’s new system of privatised Medicaid. It gives politicians bragging rights but it hurts the disabled. The media ignore the patients.

Most excellent links. Certainly provides escape velocity from the very narrow academic focus of this study.

Medicare in the intro should be Medicaid

Aargh, will fix. Thanks!

I am trying to understand why the issue of what type of organization offers a service is important.

Are VA doctors less compassionate and competent than private doctors or doctors that accept Medicare or are in some private insurance network?

Is a military person who is a volunteer (and therefore a mercenary!) better or worse than someone who was conscripted?

The economic question seems to come down to the following: If you add up the direct costs and attempt to include the indirect costs, is there a real difference in the cost and quality of the service being provided that depends on the kind of organiztion providing the service?

Note: I exclude scamming or con artists from this discussion.

As far as I can see, it is seldom possible to prove that a government service is or is not truly more or less expensive or is truly better or worse than a private service. If this is more or less true, than what value is all the discussion?

“I am trying to understand why the issue of what type of organization offers a service is important.”

It is very important to the people who want to restrict provision of that service.

As Lee Atwater said, the primary governing philosophy of a substantial group of voters in the United States is “Blacks get hurt worse than whites”.

It’s not about providing the best service to all. Once you reject the idea that “All humans are created equal”, you open the door to ensuring that government services are awful, so that anyone who has the money to buy better services doesn’t use them.

The demand for privatization is a symptom of a much larger fight.

It worked so well in Kansas ….

https://www-1.kansas.com/news/politics-government/article127412554.html

And in Iowa…

https://www.desmoinesregister.com/story/news/politics/iowa-poll/2018/09/26/iowa-medicaid-privatization-support-drops-28-percent-iowa-poll-governor-kim-reynolds/1408907002/

and in California: Medi-Cal Sued For Pushing Patients Into Managed Care Despite Judges’ Orders

The article doesn’t state it but the young woman referenced in the piece is clearly disabled. Though travel wasn’t mentioned in the piece, I’m betting the severely disabled are now afraid to even visit anyone out of the counties they live in.

It’s a pretty terrible and superficial analysis. Doesn’t even come close to an analysis of outcomes. Aside from the prescription part being erroneously pegged to the privatization, the hospital spending may indicate poorer or better outcomes.

Here in KY we’ve had privatization for about a decade, phased in over time, starting with the Louisville area with a nonprofit running the show. When it was rolled out to the rest of the state they opened it up to private corporations. Anecdotal evidence from all over the state suggests that the private companies suck. They are horrible to deal with and make getting care difficult. My wife deals with this on the mental health side. But nearly everyone likes the nonprofit company.

But then our little Trump administration changed the reimbursement rates for the nonprofit in order to drive it into bankruptcy. Because god forbid the nonprofit sector do something better than the for profit criminals.

That’s how things work in modern Amurica.

“Anecdotal evidence from all over the state suggests that the private companies suck. They are horrible to deal with and make getting care difficult. ”

this is my experience with Texas’ medicaid “provider(s)”…Wife’s experience has been better(feels like cancer is taken more seriously than my bone and joint issues…triage? clear diagnosis? idk. shouldn’t matter)

the Clawback issue…which i didn’t even know about until after i was finally on the program(ssi/medicaid)…is a perennial worry.

it’s difficult to get a straight answer(hell..it’s difficult to get a human on the phone(let alone a human who knows things)).

anecdote is abundant…none of it good or comforting.

just one more way to punish the poor…thought up by republicans, made manifest by bill frelling clinton.

“Dick Swenson

October 17, 2019 at 5:34 pm

I am trying to understand why the issue of what type of organization offers a service is important.

Are VA doctors less compassionate and competent than private doctors or doctors that accept Medicare or are in some private insurance network?

Is a military person who is a volunteer (and therefore a mercenary!) better or worse than someone who was conscripted?”

As far as the milservicemen goes, absolutely, volunteers are much better soldiers on average than are draftees. To quote Napoleon Bonaparte: “One volunteer is worth three conscripts”. Likewise, if the cause is clearly unjust, there is a real moral difference between volunteers and conscripts, this time in favor of the latter.