This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 1327 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser and what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current goal, expanding our reach.

Yves here. We are pleased to help publicize the first recipient of the Archie McCardell Award, which we hope becomes an important badge of dishonor in Corporate America.

I assume that the reason that WeWork received the award, as opposed to just its CEO Adam Neumann, was that for a high-profite, supposed tech wonder to be such a governance mess, on top of its now-well-known operational and business howlers, took a lot of parents.

WeWork had Silicon Valley funders as well as Softbank, meaning grownups who had operating brain cells chose to put good money into a company that now looks to on a fast track to bankruptcy. With WeWork seeking a valuation of $48 billion in its IPO, this is an even more dramatic reversal than the $9-billion-at-its-peak Theranos, and there wasn’t even widespread fraud in the picture.

And even though securities underwriters are very careful not to take financial risks,1 the lead manager of the shelved IPO, JP Morgan, also deserves a heaping dose of opprobrium for putting its name on the widely-ridiculed prospectus.1 Similarly, Rebekah Paltrow Neumann, CEO Adam’s wife, played a prominent role in company management, with her New Agey meddling. While cults are an effective business model, all she seemed to do was add considerably to the flakiness of WeWork’s practices. so she also bears culpability.

By Michael Olenick, a research fellow at INSEAD. Originally published at Innowiki

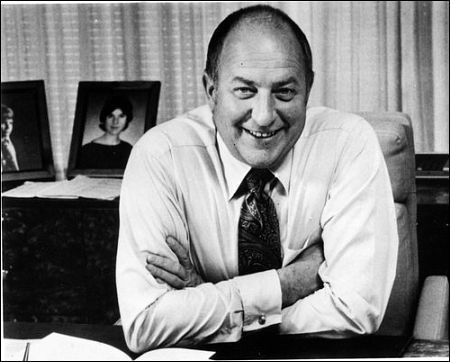

Archie McCardell is the worst CEO in history.

Sure, there are CEO’s who committed crimes, CEO’s who bankrupt their businesses, and CEO’s who looted their businesses. There are crooks, those who hire cronies, people who paid bribes, plenty who demanded sex or servitude, and countless sociopaths.

In fairness to him, Archie did none of these things. Which makes winning his place as the worst CEO of all time all the more remarkable.

Background

McCardell is a University of Michigan MBA who started his career at Ford focused on finance. At Ford, Archie trained under Robert McNamara, the future US Secretary of Defense. McNamara is a key person who fabricated the Gulf of Tonkin invasion by North Vietnam to justify a massive escalation in the Vietnam War. Eventually, by the time the US effectively surrendered on March 29, 1973, 57,939 Americans and about a quarter-million South Vietnamese died in the conflict. Vietnam remained communist for about a decade then eventually transformed to capitalism, proving the entire war pointless in hindsight. McNamara trained his prodigy, McCardell, well.

Xerox

After Ford, Archie started at Xerox in 1966. They promoted him to president in 1971. For three years, Xerox continued to announce record profits, just as they had for the prior two decades. Xerox had two research centers, one in New York and the then-new Xerox Palo Alto Research Center, Xerox PARC, in California. Significantly, McCardell pushed the Rochester center for profits but largely ignored the quirkier California group. Later, Archie’s executives were ready to cancel a New York-based project led by Gary Starkweather to image a copier drum by lasers, the laser printer. However, Starkweather negotiated a last-minute relocation to Palo Alto and saved his project.

Other interesting projects happening in Palo Alto, a center set up before McCardell’s time, included computer work building on Douglas Engelbart’s work at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI). Engelbart demonstrated video teleconferencing, intuitive interactive interfaces for computers, editable lists on computers, windows, dynamic file linking, and a new input device, the mouse. Subsequently, Xerox PARC hired many of Engelbart’s researchers and supplemented them with others led by the legendary Robert Taylor.

Archie Blows the Future

During McCardell’s reign, Xerox PARC created the modern computer interface, building on and perfecting windows, the mouse, icons, visual files, and intuitive interactive computing. Eventually, they created the idea of the personal computer, internally called the “Dynabook.” Object-oriented programming, the building block of all modern computer systems, came from Xerox PARC. Ethernet networking, which is how virtually all computers connect (WiFi is wireless Ethernet) is from there and so are spline fonts and What You See is What You Get on-screen displays and printing. And, of course, Starkweather perfected his laser printer that also came from PARC.

McCardell purposefully threw it all away. The Xerox Alto, developed at Xerox PARC, was the first modern personal computer. The Alto is the Mac before the Mac. “At Xerox, McCardell and [Ford alum head of engineering Jim] O’Neill created a numbers culture where decisions were put through the NPV test. Not surprisingly, the Alto failed,” reads an analysis.

After he left Xerox, they’d eventually commercialize an enterprise laser printer but the executive team he put in place – and the toxic environment Archie left behind – ignored the most valuable technology since the invention of the internal combustion engine and the car.

Simultaneously, while ignoring all the PARC technology, McCardell also ceded Xerox’s core copier business to the Japanese.

Blowing the third industrial revolution should be enough to secure McCardell’s position as the worst CEO ever. However, most historical records barely mention Archie’s disastrous Reign of Error at Xerox. He was just getting started.

International Harvester

In 1977, Archie took over as CEO of International Harvester. At this time, International Harvester was the third most valuable American business. McCardell’s starting salary was $460,000, making him one of the highest-paid CEO’s in the world. He also accepted a $1.5 million signing bonus and a $1.8 million loan at 8 percent (an interest rate which, at that time, was considered low).

Quoting the Washington Post: “The company had been directed primarily by family members since its founding by American inventor Cyrus McCormick in 1831, but the board decided it was getting stodgy and turned to a high-powered executive from the outside.” Management consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton advanced the perception an outsider was needed and recruited McCardell.

Archie cut spending by $640 million and invested $879 million, over three years, into modernization. The latter figure seems impressive except it was essentially just copying International Harvester’s competitors.

Eventually, in the fall of 1979, Archie tired of trying to grow the business or cut costs traditionally and opted for a different approach. He purposefully picked a fight with the United Auto Workers, the trade union virtually all plant workers belonged to. McCardell insisted on pay cuts and increasing the use of non-union labor.

An American Icon, Destroyed

Archie singlehanded caused a 172-day strike that began November 1, 1979, the longest-ever strike at International Harvester.

By the time the strike ended, International Harvester lost $479.4 million then lost an additional $397.3 million in the next fiscal year directly due to fallout. In the end, the union conceded virtually nothing. International Harvester’s suppliers were devasted; the strike bankrupted Chicago’s Wisconsin Steel.

Besides the losses, International Harvester’s inability to deliver caused a loss of customer confidence. Sales slid by almost half. The business took on debt to keep the company afloat, eventually reaching a staggering $4.5 billion of early 1980s high-interest debt.

McCardell restructured the debt to $4.15 billion, cut $200 million, and demanded union concessions. At the same time, Archie paid out $6 million in executive bonuses. Seeing the dismal condition of the firm, the union agreed to $200 million in wage and benefit cuts.

The union agreed to contract concessions on May 2, 1982. Archie was fired the next day.

The firm’s stock, trading in the mid $40s when McCardell was hired, traded at $2 by the time he left. International Harvester was forced to sell off many business units, including the venerable farm machinery division. Eventually, 6,400 jobs were lost. What remained was renamed Navistar.

Epilogue

“I don’t think we made any one major mistake,” McCardell said in a 1986 UPI interview. “I feel very good about my years at Harvester.” Later, he adds, “I think I was underpaid.” In a different interview with the New York Times he said: “I think I rate myself superb.”

Pundits aren’t as enthusiastic. One speculated he might have been carrying out “an industrial sabotage operation.”

Archie didn’t do much after International Harvester. There was a land development project he labeled “a disaster.” He launched a turnaround business but refused to name his clients noting that knowledge of his involvement could “add to their problems.”

McCardell did have one insight that resonates: “I don’t know many CEOs who didn’t reach their positions without some good luck along the way. I had incredibly good luck as a young man. I also had ability, but luck plays a very important part,” he told UPI.

Archie McCardell died July 10, 2008, as the US was heading into the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression.

Archie McCardell Award

Inspired by true events we realized Archie’s management talents aren’t unique. Granted, nobody is likely to replicate his success decimating two businesses in entirely separate industries. Archie’s ability to destroy was positively Romanesque in scope, unlikely to be repeated anytime soon.

However, their failure to fail, and to flame-out spectacularly, won’t be for lack of ambition. In this spirit, we’ve decided to create an award, the Archie McCardell Award, for absolutely horrendous management.

Archie McCardell Award Winner: WeWork

In the summer of 2019, commercial rental space company WeWork was valued at $47 billion. That’s $47,000,000,000 US dollars, not Nambian. By September, founder Adam Neumann was out as CEO and the business was hoping for a $10 billion valuation. As of October, the scuttlebutt is they may be bankrupt. From a $47 billion to an impending bankruptcy within a half year. Adam, we salute you. You’ve earned the first Archie McCardell Award.

Personally buying buildings and leasing them back the company, secretly owning the company’s trademark, filling your buildings by offering free wine and beer, and smoking pot in the $60 million company jet are the types of things needed to win a coveted Archie. Selling $700 million of your own stock while urging the public to buy the same would make Archie proud. Throwing a wild party featuring a famous DJ after a significant round of layoffs. Jumping on desks and tables barefoot to yell at people (Archie sent armed thugs but, hey, it was a different time).

Adam aspired to be the world’s first trillionaire, and Archie was the world’s first executive to blow a trillion-dollar opportunity; you’re like brothers from different mothers.

Neumann renamed WeWork to just “We” before the planned IPO, filed Aug. 14, 2019, in anticipation of expanding the brand into every corner of life. His circle-of-life idea wasn’t just something the company talked about; they lived it, doing things like insisting on listing the IPO underwriters in a circle:

You can almost see investment bankers sitting around a circle, with barefoot Neumann and his ever-present wife, Rebekah Paltrow Neumann, in the center. Rebekah is Gwyneth’s cousin, a fact repeatedly mentioned and somehow relevant to a business renting office space.

It’s not hard to imagine the bankers from Citi, HSBC, Goldman Sachs, and UBS wearing suits while sitting uncomfortably in the lotus position thinking “how the fuck did we get ourselves into this?” as the Neumann’s do shots of expensive tequila and harangue.

However, the bankers knew better than to say or even think that aloud, lest Rebekah fire them for “bad energy” as she reportedly repeatedly did at We nee WeWork. Rebekah needed good vibes because there are apparently kids around in a daycare she started, WeGrow. Her price per child is $22,000 for age 2, $36,000 per year for ages 3-4 and $42,000 for age 5. Her school stops age 5 but offers “mentorships” for the six-year-old and over crowd.

The WeWhatever prospectus explains the businesses secret-sauce is technology, with “1,000 engineers, product designers and machine learning scientists that are dedicated to building, integrating and automating the complex systems we use to operate our business.” I have a friend who operates a similar operation renting office space in South Florida. The only engineers he employes are those who unclog the toilet after somebody enjoys an unfortunate visit to a questionable food truck for lunch. A machine-learning algorithm might figure out who did the deed, assuming anybody really wants to know.

The prospectus has profound business insights, like this: “… each additional location not only adds members to our platform and revenue to our income statement, but also becomes profitable once it reaches a break-even point.” Who would’ve thought a business becomes profitable after reaching breakeven? This goes along with the company’s “space as a service” model which means … I have no clue. I don’t know how somebody wrote this prospectus sober, assuming that they were.

There are ten risk-factors listed and, buried smack in the middle of the pack at the #5 position, is this stinky: “risks related to the long-term and fixed-cost nature of our leases.” We commits to extremely long-term commercial leases. Their “members” (that’d be “tenants” in normal-speak) are typically month-to-month. The company has high occupancy rates during a booming economy. But economic cycles come-and-go and this one is long overdue for a correction. When that happens the free-beer tenants simply leave, no notice required, while, We keep is committed to top-of-the-market rents. We also notes a future cooling of the commercial real estate market might allow competitors to offer similar space at lower prices, poaching tenants (er, members). We, on the other hand, cannot renegotiate their lease payments downward.

In these healthy economic times, We reported six-month financials ending June 30, 2019. The company brought in $1.5 billion of revenue with $2.9 billion of total expenses. With some financial shenanigans, they reduce the net loss to a mere $690 million. That is, after the (admittedly usual) cooking of the books We still lost $115 million each and every month for the first half of 2019 despite their high occupancy rates. The company notes debt of $1.34 billion then, on page 41, quietly mentions future undiscounted lease obligations of a mere $47.2 billion.

Finally, We notes all the revenue and liabilities — really, the entire business — is owned by the “We Company Partnership” which the “We Company,” the one offering shares, owns no part of. That is, they were planning to sell what were essentially tracking shares of a crappy company, not shares of the crappy company itself.

On Monday, Sept. 30, 2019, We withdrew the IPO. Along with their public offering went a $6 billion in promised loans that were dependent upon the IPO. One of their risk factors came true: “Our future success depends in large part on the continued service of Adam Neumann, our Co-Founder and Chief Executive Officer, which cannot be ensured or guaranteed.” Adam is out as CEO though continues as Chairman. Some analysts convincingly assert the next federal filing We makes may be a bankruptcy petition.

Congratulations (former) WeWork CEO Adam Neumann, you’ve earned the first-ever Archie Award.

_____

1 Even though underwriters do nominally underwrite, as in they commit to buy all of the securities sold in the public offering, and then re-sell them to investors, in reality they pre-sell the deal. That’s why the price is often adjusted upward or downward during the “book building” process: it reflects the level of demand during the period when the preliminary prospectus is released and the deal is priced and goes “effective” (the pricing amendment is filed with and accepted by the SEC). Even though the indications of interest or “circles” are not contractually binding, any institutional investor that reneged on a commitment to buy stock once the IPO was released would find it not seeing any more IPOs (which are sought to be priced to trade up on the first day, so participating regularly in IPOs ought to be a profitable strategy for an institutional investor).

Having said that, once in a great while, an IPO goes so sour that the underwriters lose money. But this is a very uncommon event.

And the discussion above applies to equity offerings. Large debt deals by regular issuers like big banks are done on a “shelf registration” basis where the underwriters (usually one or a few of what in the old day would have been called bulge bracket firms) bid and buy the deal. So they are taking true price risk, but they typically price in the risk of adverse market moves in their bids.

2 Even though the contract between the lead underwriters and the company makes clear that the prospectus is the company’s document, and the underwriters from a legal perspective say they provided virtually nada, like their names on the cover page, the offering price and underwriters’ discount, and some language about them back in the bowels of the offering document, the lead underwriters are actively involved in the drafting of IPOs and most assuredly reviewed every word. At Goldman, I was personally involved in writing prospectuses on behalf of clients who lacked the capacity to do so. WeWork was so well funded that the company and its lawyer would have provided a complete and detailed first draft, and would also have in virtually all instances made any revisions or additions that the lead manager thought was necessary. However, the bigger point is that JP Morgan was all over the prospectus-drafting process and was therefore fully aware of what a garbage barge the company was. Ditto the other co-managers.

Morlocks, in Mordor not just grifting but breaking new ground in the pursuit of utter uselessness. It it as, was told me to – Devil I yelled, “what will you give for my soul.” The Devil a patient and practical sort, quietly, said back to me: “Why do I pay you for something I already own.” WeWork- I give you a dollar for the whole thing.

I would have to give Softbank’s CEO the award, after all he is pooling and deploying massive amounts of capital in an effort to create monopolies that one day profit. What if WeWork owned all the available commercial real estate in Manhattan? It sounds ridiculous, but that was the play. And he just doubled down on the strategy over and over, with Softbank being the only significant investor in the WeWork scam.

And Wolf Richter’s on the case. Again. Link:

https://wolfstreet.com/2019/10/06/the-wolf-street-report-how-the-softbank-scheme-rips-open-the-tech-bubble/

SoftBank is not the only company Neuman scammed.

Neuman managed to take out at least $500 million dollars in loans from JPMorgan, UBS and Credit Suisse against the WeWork stock he owns.

Yves: I think you mean Zimbabwe dollars – Namibian dollars are N$15 to US$1, whereas the ZImbabwean dollar was crushed by hyperinflation

I didn’t catch that and will alert the post author. But he may mean Namibian $.

I thought the “Nambian” dollar was a reference to this shining moment

In writing the garbage prospectus, presumably in MS Word or similar, the regular references to ‘We’ followed by the third person singular form of the verb would surely have thrown the ever zealous spell and grammar checker into a complete fizz and that then probably downed tools in disgust.

ROFLMAO!

There’s a good, readable book – I can’t remember the name it’s on my shelf at home somewhere – on McCardell’s destruction of International Harvester.

Now, it may and probably would have slid down the slope from pinnacle to just another player, like GM, but McCardell simply slaughtered it. But *I* loved that company. From the beginnings in Chicago to the greatest tractor ever – the Farmall M – and along the way refrigerators that simply won’t die and so many, many other things. The trucks were so good they survived as Navistar. The tractors were so good they survived as CaseIH. And the incomparable IH Scout….

Ah, well. The one thing to get from the McCardell, and Neumann stories and the many to follow is to remember that a major key to success is not overcoming your weaknesses, but being completely oblivious to them. And somehow extending the same “reality-distortion field” – note that Jobs failed bigtime twice – to others.

Thank you for this. You’re not the only one who loved some companies like IH. I also loved the old Sears Roebuck, and the old GM and the old Bethlehem Steel…. to the point that I purchased their “semi-official” company histories, photos, drawings, etc.

In studying them, there is one common denominator: money. In each case, when the money people take over the board, they drove the company into the ground. As opposed to a steel company being ran by steel people, a tractor company being ran by tractor people, etc etc… the pattern of failure is very evident.

International Harvester also sold Solar Turbines to Caterpillar in the 1981. Their products are preferred over similar ones from GE and Siemens and are used on oil rigs, pipelines, and small-scale (2-20MW) power generation.

I forgot about Solar Turbines, thank you.

The book is “A Corporate Tragedy” by Barbara Marsh.

My first major accident was in a borrowed International Harvester Scout.

An oncoming car skidded 30 feet through the intersection at me, hit my front end and kept going another twenty feet. The other car, a Japanese sedan of some kind I think, was totaled, the other driver just inches from having a folded in pillar hit her and surely injure her, the spiderwebbed windshield in her lap.

The Scout? It had a small dent on the fender. I drove it away, shaken, after the police had done their reporting and dismissed me as innocent.

Cue up the loud sigh from Tucson.

Slim’s weighing in on yet another coworking post, and, sad to say, this is more of the same old BS that I used to cope with every work day. While the coworking space I belonged to, er, rented a desk from, wasn’t as zany as WeWork, one of our operations managers left her Tucson position for a job at …

… WeWork.

Before she left our fair city, she had turned into quite the WeWork fangirl. To the point of turning her office, and then one of the vacant tenant offices, into a WeWork shrine. Lemme tell you, if I never see that “Thank God It’s Monday” sign again, I will live a very long and happy life.

When I asked her about the vacant office with all the WeWork-themed signs in it, she told me that it was for “our” marketing. As in, the coworking space in Tucson’s marketing. Yet, for some strange reason, I never saw that office pictured in any local promotions.

I guess that vacant office/WeWork shrine was part of her job application package for WeWork.

She also was in the habit of posting WeWork fan articles on her LinkedIn wall. And you know me — I read Naked Capitalism and WolfStreet. Let’s just say that she wasn’t too happy with me posting a link to one of Wolf Richter’s articles in the comments below one of her fan posts.

Any-hoo, she left for the coast in early March, and I expect to see her back in Tucson by the end of the year.

Even though she went to one of the biggest corporate cults of all time, she did one thing right. She got out of “our” coworking space while the getting was good. Place went out of business at the end of June.

Yes, there are other coworking spaces in Tucson. One of the newest ones is located in (you’re gonna love this) a former funeral home.

A funeral home? How apropos.

I’ve attended exactly one event at said space. I don’t know if they’re not trying hard enough or if it’s impossible to give such a place a convincing makeover, but it still looks like a funeral home to me.

And that, people, is why I am working from the Arizona Slim Ranch’s home office. I love the 30-second commute. Even better, there’s the freedom from having to deal with leases, landlords, paying rent (for a desk), and office politics.

Shinla

Cryptic comment.

Selling $20 dollar bills for $10 each is a terrific way to generate “market enthusiasm”.

The cost of that enthusiasm starts at $10 per note, plus additional losses for high risk loans, compensation for a “genius” CEO (and his wife), and no discernible benefit (aside from free beer).

I pity the innocent, but many of the soon-to-be victims are those believing that money can grow on trees. Infinitely and indefinitely.

Minor correction – shouldn’t it be ‘Namibian’ dollars?

Those are real currency…

I’ve attached a link below to a seminar put on by Ford Motor Company during the 2017 North American International Auto Show in Detroit. The seminar was about the future and Ford was announcing their plans for becoming a mobility company and provider of TaaS, Transportation as a Service.

It begins with a talk by Jeremy Rifkin about what he calls the Third Industrial Revolution and then goes to a panel discussion about the future. One of the panel members is Adam Neumann.

It is amazing to watch this and see how much of this has unraveled since January of 2017. It makes you think Detroit had become the new La La Land.

https://www.facebook.com/VICE/videos/1522323281134258/

Well that explains what happened to Xerox Alto and also why you never hear of International Harvester anymore. Reminds me of that guy, Charles F. Kettering, who decided that it would be a great idea to add lead to gasoline and then went on later to decide that it would be a brilliant idea to use Freon in refrigerators. This guy ended up being killed by a mechanical bed that he invented.

I can’t help but think that perhaps Adam Neumann, when he was with those bankers from mobs like J. P. Morgan, Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, etc., was literally the smartest guy in the room. He must have know that it was all a massive bluff on his part and yet here were all those guys who were supposedly so smart begging him to take their money.

That was Thomas Midgley Jr. He worked for Kettering. He’s in the mega-study where I came across McCardell. There should probably be a Midgley Award for environmental destructiveness but I can only handle terrible award at a time. Especially because, as so many here have pointed out, there are lots of candidates in the pipeline for Archie’s. Masayoshi Son is certainly working on one but hasn’t destroyed enough… yet. His work towards an Archie is still more aspirational than inspirational.

My mistake. You are correct – it was Thomas Midgley Jr and Kettering only worked along side him with the lead project. Thanks for that correction. I always thought that his death had a “Final Destination” quality to it.

The point stands, but I imagine you’re thinking of the redoutable inventor Thomas Midgley Jr., who, “…played a major role in developing leaded gasoline (Tetraethyllead) and some of the first chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs),” and later, “…became entangled in the device and died of strangulation,” referring to the lethal mechanical bed. Commenting on Midgley’s “achievements”, Author Bill Bryson wonders in awe how a single individual’s business ideas and efforts could be responsible for so much unaccounted for death and destruction.

Is it possible that the Mr. Kettering did not realize the environmental costs of Freon? Certainly as a refrigerant, Freon is a beautiful substance… low toxicity, non flammable, non corrosive (to either the piping or the seals of the machines), and thermodynamic characteristics were well matched to the desired refrigeration cycle. Lead on the other hand…we have a long history of knowledge of lead poisoning; systematic attempts to limit or ban its use started in the 16th century. How the hell did the regulators miss that? And why was Mr Kettering allowed to walk freely for this screw up??

“Missing” the possible problems with using lead was caused by profit. In reluctance fairness, I do have to note that the widespread environmental poisoning caused by leaded gasoline was probably very underestimated. However, not only has lead poisoning been known since at least the Roman Republic, there have been studies since the late 1800’s giving more information although the earliest one, IIRC, were crude.

The lead industry was very effective in slowing, and even stopping, even the regulation, forget banning, of lead use. They used the exact same tactics that cigarettes makers and oil companies used to discredit any information showing the problems being caused. Deny, distort, lie, and bribe. Get funding for research cut. Smear researchers. Essentially bribe legislators. The use of lead paint itself was finally outlawed in the United States in 1978 despite repeated attempts starting in the Progressive Era to stop the use of lead in general or at least strongly regulated it.

Actually, abandoning PARC was not so dumb from a business standpoint — at the time. Robert X. Cringely, in “Accidental Empires” (Addison Wesley, 1992), said, “Just the parts to build an Alto in 1973 cost $10,000, which suggests that a retail Alto would have had to sell for at least $25,000 (1973 dollars, too) for Xerox to make money on it. When personal computers finally did come along a couple of years later, the price point that worked was around $3,000, so the Alto was way too expensive. It wasn’t a personal computer.” It was more than ten years for the microprocessors of the day and integrated circuits to become well-developed enough for most of PARC’s research to become feasible commercially, and even then the MacIntosh was expensive when it finally came out.

This is wrong. It took 22 years between the first patent filing and the release of the Xerox 914, the first popular photocopy machine. Earlier copiers were clunky and insanely expensive, used only by specialized printshops that were using an even slower and more expensive process. The same timeline for the PARC work would have put Xerox releasing a commercially viable computer about 1991. By that time the Mac was about six years old. Xerox – despite an enormous cash cushion (which didn’t exist before the 914) – was reckless and impatient for immediate profits. This was short-termerism at its worst. Xerox was idiotic in abandoning the computer work at PARC. I’d dare say there isn’t an investor in the world today who, if they had a time machine, would pay Xerox virtually anything for exclusive rights to those technologies in the mid 70’s. However, there also isn’t an investor in the world today who would buy Xerox shares during the same time period.

Post Script to the Archie McCardell losses at Xerox, and mindful of the double ownership of We (the entire business is owned by the “We Company Partnership” which the “We Company,” the one offering shares, owns no part of), turn to a potential candidate for the award: Carl Icahn. Icahn famously ruined TWA, albeit by privately selling off the best routes for personal gain.

A self-styled “activist stockholder” (difference to a corporate raider TBD), he now holds controlling shares of Xerox. He won a proxy vote at the 2019 meeting of Xerox stockholders for a “holding company” reorganization. In the before-and-after diagram, there is a previously unknown subsidiary called “Holding Company” with its own subsidiary called “Merger Sub.” Post-Reorganization, Merger Sub did something magical, and “Holdings” is the top organization. It is not yet known whether the merger and holding pattern was executed and it is not known whether there were super-stockholders in the holding company.

Well deserved award and entertaining post. The saving grace, if there is one, is that in this particular instance the IPO underwriters have at least so far been unable to offload to Mom & Pop or their pension funds, mutual funds, and 401k’s.

Unfortunately, the award does divert attention away from and thereby serve to exculpate those who made the underwriting and risk management decisions at the large banks and venture capital firm that enabled the individual primarily responsible for this huge capital bonfire. As Wolf Richter has pointed out, the losses incurred could also deprive worthy start-ups of needed capital.

Like so many others, this episode will likely be obfuscated, as it again points to intellectual and ethical bankruptcy of the supposed elite; although as in other instances there are no doubt a few people who have benefitted financially from the capital flows.

Again, why do we need negative real interest rates?… to enable the existing zombies to continue, to grease schemes like this?… and/or to elevate real estate, stock and bond prices?

I would argue that Neumann doesn’t qualify for entry to the Archie McCardell Award. McCardell took two established, well-respected companies with lots of potential and drove them into the ground. Neumann’s company was a garbage barge from day 1.

I nominate as a candidate more qualified for taking an established, well-respected company with lots of potential and, literally in this case, driving it into the ground is the CEO of Boeing.

Looking back (although I don’t think past CEOs quality) I’d nominal Al Dunlap.

Albert John Dunlap (July 26, 1937 – January 25, 2019) was an American corporate executive.[2][3] He was known at the peak of his career as a turnaround management specialist via mass layoffs, which earned him the nicknames “Chainsaw Al” and “Rambo in Pinstripes”, after he posed for a photo wearing an ammo belt across his chest.[4] It was later discovered that his reputed turnarounds were elaborate frauds and his career was ended after he engineered a massive accounting scandal at Sunbeam Products, now a division of Newell Brands, that forced the company into bankruptcy.[5] …in an interview, Dunlap freely admitted to possessing many of the traits of a psychopath, but considered them positive traits such as leadership and decisiveness. -Wiki

Frauds, bankruptcies, stealing pension funds, management buy spreadsheet (see pension funds). He was, for a time, lauded in all the popular economic magazines.

It’s almost like all the builders of earlier generations were scorned by the new new destroyers. Destruction was the ‘new thing’, and since it was new it must be ‘progress’. (how else could they sell the con?) meh.

And yet, back in the 80s and 90s Chainsaw Al was lauded, heck worshiped like some sort of deity for his work as a corporate terrorist and well paid too. At constant drizzle of articles in magazines and newspapers saying that he was just awesome and his response to any questions about the welfare of both the workers and the company was shareholder value, always shareholder values. The damn stock value of the company had to always increase.

The more I read about him, the more I knew that somehow he was wrecking ball. I didn’t know enough to clearly understand and explain, but it was always cuts, layoffs, and shareholder value; just how is that a business? Parasitism maybe, but a functioning business?

I have forgot all the details but it the annual rank and rank that laid off 10% of the workforce and the almost indiscriminate chopping off of corporate units and divisions because reasons. Profits and rising stock values now, by any means, no matter the long term (like the next quarter) loss of profits, or even as just a functioning business.

What a monster.

I thought of Dunlap too.

As well as Robert Nardelli. On his slide from faux glory, he destroyed a bunch of paper companies that should have been world efficient for at least a couple of decades.

Originally I thought Archie’s were best going forward but I’m entirely open to making up the rules as we go along. Ichan has been a human wrecking ball. Ron Perelman and Ichan (in the one deal they opposed one another) were virtual supervillains of business for what they did to Marvel. Chainsaw Al is up there — or down there, is probably more accurate — though I thought maybe it’s best to focus on executives who destroy their companies without overtly breaking any laws (takes more talent). Nardelli. Richard Fuld for sure. James Cayne. Jack Welch/Jeff Immelt and deserve to share one, though the prize should probably be awarded 80% to Welch. AIG’s Bob Willumstad who pushed the CDS business. Milton Friedman should probably receive an Honorary Archie. Michael Milken deserves a win in the financial tech category. So much opportunity…

In the long ago there were only 2 serious farm implement companies in my area: green Deere and red International Harvester (IH). I always wondered what happened to IH. It was a great company. IH seemed to vanish for no clear reason. Now I know: management by spreadsheet. Management by “whatever makes me rich.” It’s good to finally know what brought IH down. I always wondered.

McCardell then went on to destroy Xerox.

Is he now the patron saint of the neoclassical economists and the neoliberal politcians?

Takeaway: Be very grateful that as much as I’ve messed up in life, I could have turned out to be a far greater screwup. This has given me hope and lifted my spirits. I feel a certain lightness in feet.