Yves here. Readers will notice a marked disconnect between Michael Olenick’s grim account of the impact of the automation of the early industrial era on workers’ lives as to his more sanguine posture for the future. One way to reconcile the two is that major shift in automation can have significant transition costs in terms of the loss and degradation of some jobs, even if overall the level and arguably the caliber of jobs overall rises.

Additional bits of information to flesh out Olenick’s account: in the early days of the Industrial Revolution (at least the first generation and arguably the first two generations) real incomes of average workers in England fell. And for the current wave of automation, some of the jobs displaced, such as that of receptionist, operator and checkout clerk, degrade the customer experience in addition to reducing staffing levels. And let us not forget that automation is also cutting into the ranks of entry level jobs like the law, where former yeoman tasks like research, which were important to learning the profession, are now being replace by computers or outsourced to India.

By Michael Olenick, a research fellow at INSEAD who writes regularly at Olen on Economics and Innowiki. Originally published at Innowiki

Right now, we have 122 major innovations that involve some type of automation. Click here to see the list. Putting it mildly, many of them were not met with enthusiasm. For example, Frenchman Barthélemy Thimonnier invented the sewing machine only to see his factory burnt down by worried tailors. The “American Manufacturing Method” using standardized parts was invented by Frenchman Honoré Le Blanc but post-revolutionary France had enough problems without alienating gunsmiths; Thomas Jefferson brought it to the US.

The first and most famous automation freakout involves the infamous Luddites.

Nobody is sure if the legendary Ned Ludd, the inspiration for the Luddites, is a real person or more of a Robin Hood legend. Ned was supposed to be a factory worker who smashed up a knitting machine in 1779.

In some versions of the story that the machine is the Stocking Frame mechanical knitter, invented by William Lee in 1589. It could’ve also been a Spinning Jenny invented by James Hargreaves in 1764. But my guess is that it was supposed to be the Spinning Mule, invented by Samuel Crompton in 1779.

Combined with improved efficiency of the other two machines, textile work transformed from largely skilled to largely unskilled labor.

The original Ludd story is unlikely. These machines weren’t like the latest mobile phone – the smallest were huge and made with lots of wood – not easily smashable even by the angriest Englishman. Plus, it’s unlikely Ned would’ve been near a Spinning Mule the year it was released.

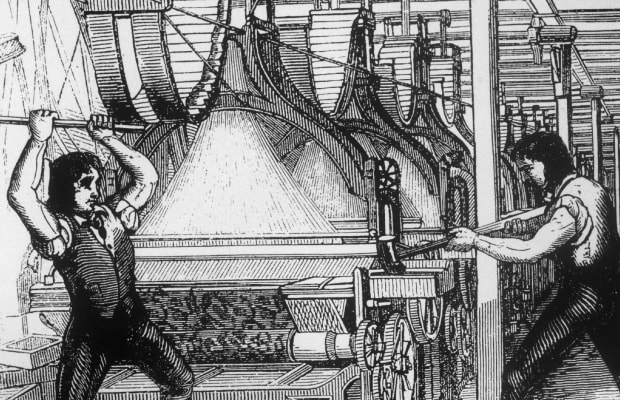

Whoever Ludd was or wasn’t his Luddites were the real deal, smashing up Spinning Mules and other automation equipment, literally back in the day and more figuratively lately.

The much-maligned Luddites had a point. Industrialist Richard Arkwright essentially weaponized the Mule and its predecessor equipment to control the lives of ordinary laborers.

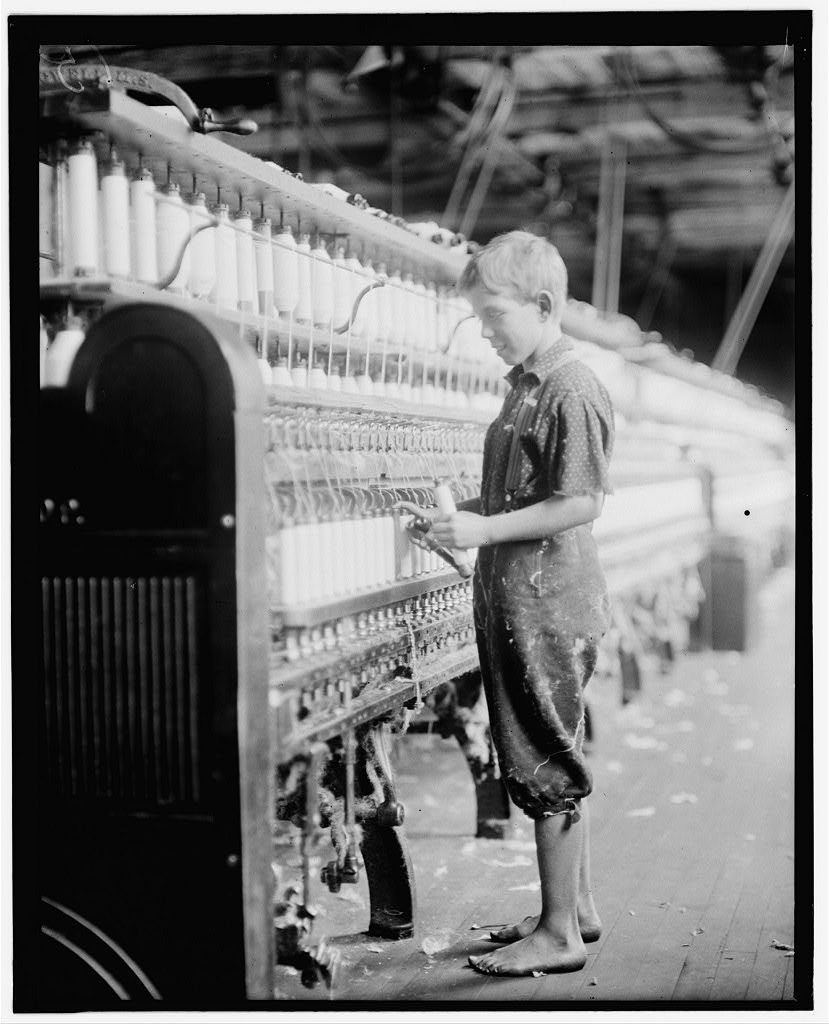

Arkwright invented the modern factory. Through the use of automation equipment, he realized high-volume mills could be operated by women and children rather than skilled laborers.

Child labor was common in England at this time and Arkwright’s factories were no exception. Technically, his minimum age employee was six but exceptions were made. Kids were especially useful for dodging under powerful looms on an upstroke to retrieve something that fell behind, waiting behind on the downstroke, then bringing it back on the next upstroke.Mistakes were not uncommon:

Cotton factories are highly unfavourable, both to the health and morals of those employed in them. They are really nurseries of disease and vice… When I was a surgeon in the infirmary, accidents were very often admitted to the infirmary, through the children’s hands and arms having being caught in the machinery; in many instances the muscles, and the skin is stripped down to the bone, and in some instances a finger or two might be lost. Last summer I visited Lever Street School. The number of children at that time in the school, who were employed in factories, was 106. The number of children who had received injuries from the machinery amounted to very nearly one half. There were forty-seven injured in this way.

Dr. Michael Ward relating conditions in an Arkwright Mill, March 25, 1819

Ward was testifying due to a government investigation caused by widespread unease. On one hand, Luddites spent months “machine breaking” in 1811-1812. The British government responded by breaking Luddites, sending 14,000 troops against their own people.

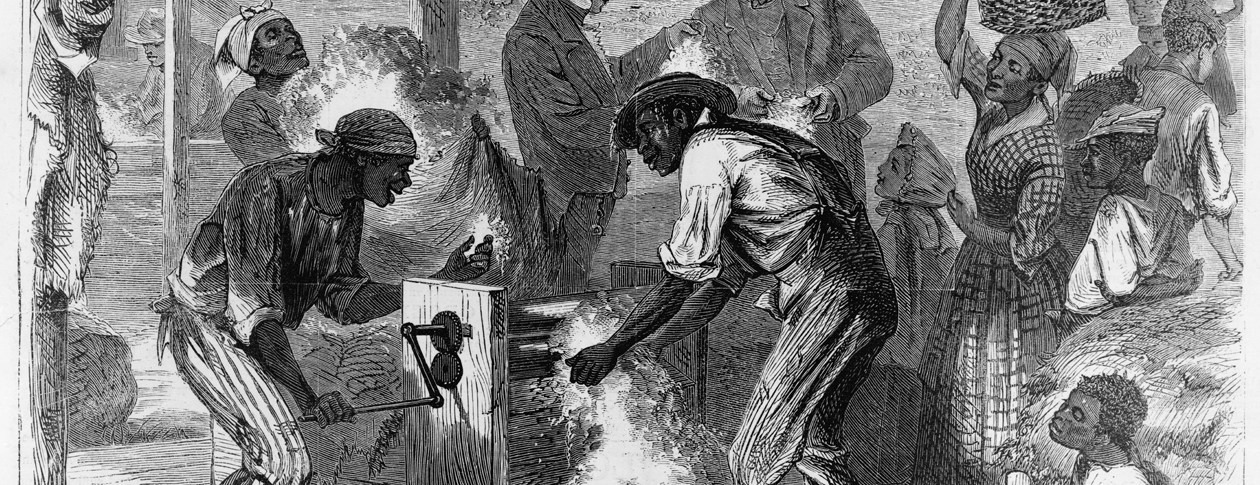

It would be irresponsible to not mention Arkwright’s mills were fed by an increasing supply of cheap cotton produced by slaves in the early United States. In the mid-1700s, growing cotton even with slaves was often unprofitable. In 1793, Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, automating the process of separating cotton from seed. The cotton gin vastly increased the profitability of slavery and resulted in a dramatic increase in slaves, including many kidnapped from Africa.

Returning to England, Arkwright’s mills expanded despite civil unrest. Waterwheels powered most mills which required they be located near fast-moving rivers. Arkwright hired local unskilled laborers, vacuuming the women and children of entire villages into his mills. The mills required ever more people so he encouraged families to move. He built the first company town, with homes, stores, and of course many mills.

Eventually, Samuel Slater smuggled Arkwright’s mill technology to the US. In 1834, the “mill girls” of Lowell, Massachusetts organized the first strike. Over the next century, countless women textile workers organized and protested. By 1912, 23,000 men, women and children organized the Bread & Roses Strike.

In 1933, Frances Perkins became the first woman in the Cabinet, as labor secretary. By then, atrocious labor conditions combined with the Great Depression caused the Textile Workers Strike of 1934, the longest in US history.

Over the years, automation ebbed and flowed but, for the most part, marched forward. We have countless innovations that contributed directly or indirectly to innovation. Despite understandable anxiety, automation tended to eventually lead to a net increase in jobs. Those automated mills the Luddites broke up led to cheap fabric and the garment industry. Clothing design, manufacturing, and retail are much larger industries. Plus, bespoke cloth and tailoring still exist.

Of course, a net increase doesn’t help the jobless with little or no skills.

Automation went on to destroy countless other jobs but, for the most part, they were awful jobs. Harvesting machines vastly decreased the number of people needed to pick corn and, later, tomatoes. Tomato pickers protested the invention of the tomato harvesting machine, predicting the end of manual labor. Of course, that didn’t happen and there were plenty of jobs picking other crops. The stepping switch and later computer tech largely eliminated the need for switchboard operators. While the job paid the bills (barely) it was boring work.

Nobody knows what will happen as advances in artificial intelligence make things like self-driving cars a reality. Like the many other innovations here, there will no doubt be some amount of displacement. But will a substantive number of good-paying jobs disappear? Or will drivers find something similar but different which computers aren’t good at, while tireless robots pilot cars that rarely if ever cause accidents? Can’t radiologists find something more interesting to do than examine the same images repeatedly, with boredom often causing mistakes? Do pharmacists really need eight years of school when computers more accurately watch out for drug contradictions?

We can’t answer any of these questions except to say that, if history is a guide, all this tech will cause more jobs, not fewer, and those jobs will be more interesting.

Good news for taxi drivers: self-driving tech may crash and burn!

The problem with the article is clear. The robot replaces the producer. It reflects production without consumption. Estimates are that by the end of this decade 40% of the EXISTING work will be gone. This is only the beginning.

What is needed is NOT the Luddites. Class consciousness that understands private property must be eliminated. A cooperative society is on the horizon .

If history is a guide then let’s consider it more closely. Automation may create more jobs in the proverbial long run but how reassuring should that thesis be to vulnerable workers of today and tomorrow? The Luddite constituency rendered redundant by technology was made to suffer for a long stretch of their lives: “In the late 1810s and throughout the 1820s, outright unemployment was becoming the primary cause of destitution” in England due to an “over-supplied labour market” as displaced artisans sought scarce work. (Agrarian Capitalism and Poor Relief in England, 1500-1860, by Larry Patriquin) Although the modern economy is far more dynamic, realizing opportunities for labor reorganization is of course not just a matter of former truck drivers taking a short course in coding. For many in their prime working years, today’s 122 major innovations in automation that the author mentions might close more doors than they open for a quite a while or at least at critical junctures in their lives.

Another historical point of interest: the Luddite rebellion effectively ended only upon execution of 24 of their members. Some questions really worth considering if using history as a guide: What penalties will be enacted for the displaced or other outraged Americans who try to disable automated trucks, for instance? And how repressive must enforcement be if/when the neo-Luddite constituency numbers in the tens of millions? Like Americans today, the original Luddites also faced a slackening economy.

As for those “more interesting” jobs envisioned by the author, they must look like pie in the sky to today’s Amazon warehouse workers and call center employees — pioneers in the integration of human labor with productivity-enhancing automation. Indeed, pharmacists may not need eight years of training nor the concomitant knowledge to man the medication desk at Walmart; instead of helping to manage people’s prescriptions, men and women still in white aprons for assuring effect might instead stand ready to refer customers to an automated quality-control hotline when, well-incentivized by fear, those customers identify inevitably incomplete data fields churned out by the automated medication management system that is abstractly responsible for doing what was once a pharmacist’s job.

So how about we consider that automation may henceforth (already) create “awful” jobs at the same rate that the author notes it destroyed over the previous 200 or so years?

In any case, the Luddites weren’t just anti-machine they were also aghast at the exploitative capture of labor-dependent profits by employers/owners. How do you measure the utility of a “more interesting” job when it pays a pittance?

In short a simple and sanguine conclusion to an essay that punts on the question posed in its title. As the author is just now a research fellow I hope in the future he can dig a little deeper and venture some answers based on closer scrutiny.

“Nobody knows what will happen as advances in artificial intelligence make things like self-driving cars a reality.”

You mean getting people out of cars, redesigning infrastructure, people making all the adaptations, and saying “look how intelligent the computers are.”

i dunno, i seem to see a lot of college grads working in interesting barista jobs and the like.

But due to automation? Or due to outsourcing etc.?

Plus due to the fact that college grads have been overproduced relative to the jobs that previously required them, so some of them would, even with NO deterioration in the job market due to outsourcing/automation/etc., end up taking jobs that don’t require a degree. IOW just due to increased supply without any changes in job market demand.

Just a few odd notes first. Olenick was talking about the invention of standardized parts by the French that was exported to America but if you skim the book “Artillery Of Napoleonic Wars” by Kevin F. Kiley you will see that this was a European wide movement at the time. Napoleon himself standardized French Army wheels from three dozen down to about a dozen and there was standardization of calibers, carriages, fittings, etc during this era.

And as far as the Luddites were concerned, the machine breakers of 1830 would be a more instructive example to use and I can assure him that reading many accounts of this fight, these machines were well capable of being destroyed. The reason these workers went after these machines was because they did the work that workers would do at a time when they needed money to tie them and their families over during the freezing winters. No money meant being dependent on the mercy of the parish.

The thing is, the contention has always been that for all the jobs that are destroyed by the introduction of new technology, new jobs will arise in their place after a transitional period. This may be true and there is proof to be found but what if this “law” was also subject too the laws of dominishing returns? That is, over time you will see fewer and fewer paying jobs arise to replace those lost to technology. This would be a very disturbing development this and we have seen that the jobs arising are crappified ones that have minimal wages, worse conditions and no recourse for any injustices. These bear little resemblance to the jobs that they replaced.

Finally, looking at that foto of the “Mill Girls” of Lowell makes me realize what a long way that we have come. If you could bring those girls into the 1970s, give them a makeover, give them modern clothing, educate them into women’s rights and those of the workplace they would think that they were in Paradise. Bring them into 2019 and they would be, as Eloined pointed out, workers in Amazon fulfillment centers. Yeah we are back into 19th century work practices with a high-tech gloss over. All that is missing is the child labor.

“child empowerment”

Standard dimensioning of mechanical parts was a revolutionary innovation.

Today we still use the ‘Renard Series’ invented in the 1870’s in the format of standardised collections of Preferred Numbers for mechanical parts and the abundance of E-Series numbers used for electrical components.

Le Blanc innovated the idea in 1777, a few decades before the Napoleanic Wars. It is described in an 1806 book.

I explain it briefly (all the innowiki entries are short), here, with links to the book and Jefferson’s letter describing the process:

https://innowiki.org/interchangeable-standardized-parts-the-american-manufacturing-method/

Indeed. The owners automate to reduce labor, they don’t do so to create more and better jobs. The reason that in the long run there are more jobs is because in the long run, at least so far, there have always been more people. So the number you want here isn’t total jobs, it’s the percentage of the eligible workforce that is productively employed.

Existing automation lets me do the equivalent work of a whole slew of circa 1850 accountants, but even that isn’t enough. The automators are coming for the rest of the accounting world too, to name just one profession. I know this because ironically, I do accounting involving the accounting automation industry.

” The owners automate to reduce labor, they don’t do so to create more and better jobs. The reason that in the long run there are more jobs is because in the long run, at least so far, there have always been more people. So the number you want here isn’t total jobs, it’s the percentage of the eligible workforce that is productively employed.”

Ummm, no.

Automation is used to increase productivity, which reduces the labour for a given output, or permits greater output for the same labour.

Increase in population does produce more workers, but it also produces more demand.

The real invariant is the amount of labour available per capita. You can’t realistically and efficiently get more than about 48 hours a week, at most, out of a typical worker.

The effect of producing more for the same amount of labour is what permits an increase in real effective wealth for the workers. Without the growing productivity, the work force would not be able to have the goods and services they do.

In fact, the only reasons we are not in a major labour shortage are (1) ‘importing’ labour through offshoring or immigration and (2) women moving into the work force, effectively doubling the pool of potential workers. These two factors coincide with major increases in automation and other methods of increasing productivity… were your thesis true, greatly increasing the labour pool plus increasing productivity should have resulted in massive unemployment.

I stand by my original statement.

Official unemployment may be low according to government statistics, but that doesn’t mean the same thing as a workforce that is productively employed. Large numbers have left the workforce, are working fewer hours than they’d like, or aren’t being compensated even close to fairly.

Just because most people can scrape up enough to get a cell phone and flatscreen doesn’t mean everything is AOK.

And I’m really tired of this idea of a labor shortage. Most of the problems on this planet are at root caused by overpopulation. We produce more and more cheap goods designed to wear out quickly so we can go ahead and produce some more, because of our warped capitalist system. We could and should be able to make do with a lot less.

The problem isn’t not enough workers, it’s too many businesses – all competing to produce more crapified goods and services than anyone really needs,

Both of you have good points. What I do disagree with is that there seems to be fewer businesses, fewer kinds of specialty businesses or products that are not non-standard and well made.

I can no longer go to a jewelry store, good stationary, art supplies, office supply store, or hobby store for jewelry, watches, good writing paper, fountain pens, ink, modeling paint, craft paper, games or paint brushes. I can go into a fewer number of chain stores selling the exact same limited numbers of products like cheap line paper, ballpoint pens, and other junk. And lots of coffee to drink while using by over priced Apple stuff.

So the number of jobs as well as the variety and quality of merchandise is getting worse. The unemployment numbers are artificially low with much of the employed unemployed.

Most of the increased “productivity” of the past twenty years seems to be ways of doing just enough to keep a business running. Then using the fewest number of people possibly, overworking most while paying as little as possible. Then sending all the extracted wealth to as few as possible. That is the increase in productivity.

It is like burning down the house in winter while claiming how efficiently you are keeping warm because no fire place is needed and nobody had to chop firewood. Increased productivity!

Sorry, but we do know because is is happing now: AI/MI will be primarily used to first create virtual border checks and fences that can do adaptable online screening of large populations, separating the ‘proper people’ from the ‘unwanted people’ (shopping, border controls, total surveillance). Self driving cars are a media distraction and will not happen in 50 years time unless some ‘new physics’ is derived, because we simply still don’t know how to build the kind of ‘intelligence capable of reasoning*’ that a self-driving car will need to be reliable***.

Then they will be applied to ensure that all of that wealth civilisation is capable of producing will end up in ‘the proper pockets’ and not wasted everywhere else (economic- / socio-economic- modelling, machine trading, news- and media services).

Computers can accurately and much more quietly assign social services, drugs, treatment and medication given to ‘unwanted people’ so maybe we can shorten their lifespans by maybe 20-30** years and not ‘only’ the 10-15 as is the case now; Manually and with the constant risk of somebody going indignant about it and maybe some people taking an interest in the blatant unfairness of it (the 10-15 years is in Scandinavia, BTW)!

The most intelligent thing about the application of AI/MI is that nobody questions an algorithm!

Everyone with ‘more money than God’ are piling into AI/MI exactly because they really want to be the ones designing ‘The One Algorithm to Rule Them All’ and sell their ‘Solutions’ to Government, so that their money can finally get some hard kinetic power placed behind it’s rather tenuous influence.

*) A two-year old can one-shot things like ‘this is a giraffe’ that 500 graphics CPU’s will spend 2000 kWh’ of electricity to maybe get right most of the time, depending on lighting and hue. And ‘this object is a chair’ together with ‘this object can be used as a chair’, the latter is a trivial thing for a 2-year old but will not be learned by the current crop of MI/AI. MI doesn’t understand, it ‘only’ does correlation within very large datasets.

**) ‘Killing the Unworthy’ is very likely to be one of the prime-directives that an AI/MI algorithm will eek out of the datasets when tasked with something utilitarian but nice-sounding like ‘optimising the lifetime health of the total population’ and AI/MI can learn to cheat and hide information on how it is cheating!

***) We can do self-flying planes (to some degree of reliability) and self-flying missiles perfectly because we can map the hard physical model to a Kalman Filter, which we understand, we can guarantee proportionality between sensors and response, and we can explain to regulators how this is. That is absolutely not the case with the algorithm-blob of correlators that ‘drive’ a self-driving car: An adverse input can cause any response and we won’t know that until it does because the sensor inputs are just too complex to test for all cases! The car has to ‘figure it out’. That is another level of intelligence.

>separating the ‘proper people’ from the ‘unwanted people’ (shopping, border controls, total surveillance).

Oh my, you’ve got it. The stupid “AI” won’t be able to drive a car for, like you said, another 50 years if ever… but it sure can constrain where the car *is driven*. Wow that is scary stuff. And it will all be wrapped in the mantle of “safety”…. you don’t want to accidentally wind up where those scary brown people live!!!

New tech doesn’t have to be perfect. It just has to do the job better than people do it.

Something to note is that the ‘new tech’ to be concerned about for the creation of job loss doesn’t just mean some brand new idea but it includes the marginal improvement of existing technology.

There is a major qualitative difference between the automation of yesterday and the automation of today. Today’s “machines” are adaptive, phenomenally fast, and have access to (almost literally) the world’s data.

Furthermore, the rate of evolution of these new machines is accelerating; the cycle time for innovation is shrinking, and soon (already) the computers will alter their own software as they learn.

Furthermore, if the new jobs enabled by automation really were going to happen “after a short adaptation period”, would that adaptation period not be over by now? It’s been decades since computers and the Internet made the scene, and I’m not seeing a lot of new industries emerging which provide good jobs.

The reason the middle class is shrinking is because the middle class sells labor, and every year less labor is required – due to automation – for the same amount of production.

Labor automation is a legitimate worry, if you are the worrying sort.

If you are the adaptive sort, then it’s time to get good at automation.

“The reason the middle class is shrinking is because the middle class sells labor, ”

Very interesting point.

The people below the middle class also sell their labor, don’t they? That accounts for the lack of any gains in income there?

Even a lot of the people above the middle class sell their labor, don’t they? But they sell labor that that is harder – so far – to build software to replace?

Does anyone have books they can recommend – for the lack of a better phase – on the history of job automation?

Not a book. A few links to Practical Machinist where the topic of automation is but one of many.

https://www.practicalmachinist.com/vb/

https://www.practicalmachinist.com/vb/robots-and-automation/

https://www.practicalmachinist.com/vb/cnc-machining/

https://www.practicalmachinist.com/vb/cad-cam/

https://www.practicalmachinist.com/vb/edm-machining/

These are forums with a wide range of discussion. More to read than you have time for, but it’s a start and there is a lot of historical information on machining, and machine tools.

I have an interest in how things are made and the history of machining and machine tools and during my work life have seen how it’s done by selling my labor, with a long term strategy. After my apprenticeship I changed jawbs yearly, with the goal of getting into making different types of tooling and learning, learning, learning as much as possible and it took a few years. I saw too many guys (and they were all guys, with practically no women in the trade) wrench the same set of dies over and over again, and I didn’t want to be that guy. You stop learning within a year. That experience didn’t get me any more money, shop owners are notoriously cheap and I’m a crappy negotiator, but eventually I was able to give them all the finger, and create my own means of production, which was the point of becoming a toolmaker in the first place.

Unfortunately for young people today, that strategy would backfire as the constant surveillance and automated hiring process would single you out as an unreliable worker. It sucks to be young.

If you are the adaptive sort, then it’s time to get good at automation.

Not so sure being adaptive will remain a significant option.

It should be stressed, software is already writing itself for more and more sophisticated tasks. The “interesting” jobs are going the way of the menial jobs with little differentiation. It won’t be long before automated creation of technology can screw up in a massive cascading manner and we won’t be capable of figuring out why in any critical time frame.

“If you are the adaptive sort, then it’s time to get good at automation.”

How can that possibly work for everyone? Fallacy of composition. And if it can’t, it’s not much of a valid social approach.

One is also reminded that during the victorian era the population of England was rising rapidly (John Stuart Mill was arrested for distributing information about birth control!). So it is arguable, even then, if ‘automation’ created those poor working conditions – or an oversupply of labor relative to demand. People didn’t work in those dark satanic mills for low wages because they had been built – they worked there because there were too many people competing for too few jobs in the rest of the economy.

As far as AI taking our jobs, remember: it is one thing for a million dollar machine sitting in a laboratory to sort laundry for a TV special, and quite another thing for a machine to compete with disposable $2/hr human labor day in and day out under field conditions. Right now, we are using less automation, not more! That’s why productivity numbers are stagnant and declining – they should be shooting up if automation were having a large effect, yes? We’ve known how to make automated shirt-sewing machine for decades, even pre-AI, yet virtually all of our clothes are sewn in Bangladesh by hand. Apple computers used to be made on automated assembly lines in the United States, now iPhones are assembled by hand in Asia by armies of poorly paid workers using magnifiers and jewelers screwdrivers. It’s not that we can’t automate these jobs – but that, with cheap enough labor, the high capital and maintenance costs of automation are not worth it.

Automation does not, in general, drive down wages. Automation is typically a response to high wages.

Right now, we are using less automation, not more! That’s why productivity numbers are stagnant and declining – they should be shooting up if automation were having a large effect, yes

Yes, unless automation does not increase productivity which would make it a very bad thing. Also, for some people any wages are too high wages. As to self driving tech, If I could go to some far corner of the earth an locate a person who has never seen a car and in probably 15 minutes (after the initial stages of disbelief by the person) they could learn to drive a car. It’s easy for humans. Not so easy for computers and imo not something that is within reach without creating AI only highways for the corporations who own the tech. Socialize costs, privatize profits.

TG:

I agree with part of what you said, e.g. that there are some jobs that, at the moment, aren’t worth automating.

But when the job pays enough, and is characterized by well-known actions/functions that are repetitive and/or very similar …even if a lot of physical dexterity is required…then automation happens.

Manufacturing has far, far fewer jobs here in the U.S. than it did 40 years ago. The same has and will continue to happen with software (fewer people do way more). Manufacturing productivity is waaay up from where it was 40 years ago. I hear that from the people that sell machine tools to subassy manufacturers in the auto supply chain (and people with decades of experience, btw).

With respect to Apple products assembled with “magnifying glasses and jeweler’s screwdrivers”…that’s the final assembly of components, TG. If you were to examine the subassys, like the boards, screen, keypad, chips…you’d see almost complete automation. The final assembly function is probably 5-10% of total mfg’g cost, if that. And it doesn’t take much training, either, to do it.

If I had to guess why productivity increase rates have dropped off with respect to the non-mfg sectors, it may be the lull between storms. Automation just got language, vision, cheap sensors, machine learning, networks…that’s an awful lot of powerful tools to bring to bear on a problem.

It may also be partly because a great deal of manufacturing was offshored, so the productivity increases are occurring elsewhere in the world.

Lastly, I hope that you are more right than me, TG. I like your idea better, but I don’t (yet) believe in it.

They worked in those dark satanic mills because the Commons had been taken away from them. The saying among the elites of the day was, “There are fewest poor where there are fewest Commons”.

Ironically enough, those workers lives were made even more wretched by the “Company Store” model they lived under — the elites (who had created this situation) consistently understated the actual cost of living, leading to the urban ghettoes that Charles Dickens wrote about. Many of those elites descendants occupy what is now the House of Lords. It never occurs to them that wages are too low to deal with reality.

I would argue that we have the same system here in America today.

I think there is a major qualitative difference between the automation of the early industrial age and today. Textiles is a great example. Hand-made textiles were radically expensive. It required serious skill and time. Automating the creation created textiles that were pennies on the dollar in comparison. Because of that, the making and use of textiles exploded as people for the first time ever could purchase new clothing that required no or minimal alterations. That explosion created vastly more jobs than it eliminated because it allowed other industries to grow vastly in size.

So how does that relate to today? What great new invention is reducing the cost of something to such a small number that vast new industries are being created that to employ the displaced people plus millions more? Are self-driving cars vastly reducing the cost of transportation? If so, what new industry happens because of that? My personal belief is that the low-hanging fruit has been plucked, and there are zero new inventions that are going to drive costs down to a point that new industries will spin-off to create millions of new jobs.

And now, let’s add other ugly issues: even if something came along that required millions of laborers, why would those jobs be created in the USA? Why not Vietnam? And let’s not forget that “jobs” is something that you have to do, not something you want to do. The only thing that made industrial work rewarding was a thing called the “labor union” (I know its an unfamiliar term to youngsters), because you could make decent scratch and have a decent life. That’s gone the way of the dodo bird.

Yes, I’m pessimistic.

What new industries that employ a lot of people have been created in the last 70 or so years due to automation?

The only one that comes to mind is computers. But was that due to automation?

Where are updated Input / Output tables when you need them…

Automation isn’t the problem — it’s the people who are content to consign those displaced by it to the ash-heap of history that are the problem.

And as technological advancements speed up, the rate at which people are displaced only increases. So we need to get better at ameliorating the socioeconomic disruption, or the problems will only metastasize.

Will Further automation will increase Carbon Dioxide emissions?

We replaced humans and other animals, with electricity, or petrol (gasoline).

On a complete life cycle cost, including environmental costs, is automation cost effective? Today we do not price in the externalities (Climate Change).

+1

Given the author’s invocation of several notable anti-automation movements in early-industrial France, I was disappointed to see no mention of the related origin of the word ‘sabotage’. A sabot is a heavy wooden clog/shoe commonly worn by people in that era, and one way to halt mechanized production lines was to throw such shoes into the machinery, literally ‘clogging up the works’. Whence the term ‘sabotage’.