By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

The title of this post (and the post on specific protests to follow) is a bit of a misnomer: I will not be able to write “globally,” at least not immediately, because as we shall see in a moment, there are simply too many protests for our small crew. Second, it’s not even clear to me that “protest” is a term that applies to all the upsets and unsettlement that’s going on; Fisher et al. (below) speak of the “current wave of contention.” However, I’ll use “protests,” identified with “street protests,” for now, even though that word highlights the visible, tactical form of movements, as opposed to their content, surely different in the cases of Hong Kong and Catalonia, say, versus Lebanon or Chile. Third, “round-up” presupposes that sourcing is good enough so that protests can be compared and contrasted using roughly commensurate information; but the sourcing, at least in English, is not nearly good enough, partly because foreign desks have been gutted, partly through censorship, partly through provincialism. (I’d welcome in-country or knowledgeable reports from readers, since I think the story of global protest will be a continuing one. You can contact me at lambert [UNDERSCORE] strether [DOT] corrente [AT] yahoo [DOT] com.)

In this post, I’ll first look at the scale of current protests, because there are rather a lot of them, so many that you would think this story deserves more coverage than it is getting. Next, I’ll look at protests from three academic perspectives: Non-Violence (Chenoweth), Data Gathering (Fisher, Andrews, Caren, Chenoweth, Heaney, Leung, Perkins, and Pressman), and Class (Dahlum, Knutsen, and Wig). In the post following, I’ll use this perspectives to look at causes of the protests, and individual cases (probably Chile, France, Hong Kong, Iraq, Lebanon, and Spain/Catalonia, though I reserve the right to change my mind on France, where censorship seems really bad.

Let’s start with some video. Here is a video of protest in Chile from David Begnaud, of CBS. As you can see, the crowd is enormous:

BREAKING: "This is a historical day for Chile," says the govt official who tweeted this video. Nearly 1 million protesters are in the streets of Santagio, Chile, now. Internet service is slowing down, as people use social media to make sure the world knows.pic.twitter.com/sUZ3GM4AR7

— David Begnaud (@DavidBegnaud) October 25, 2019

Here is a second video, also of Santiago, from journalist/documentary filmmaker:

In Chile, a country of around 17 million people, more than 1 million people r out in the streets of capital Santiago protesting neoliberalism and the US-friendly govt's repression of protest. The Western media are curiously silent about the scale of the uprising. #ChileDespertoً pic.twitter.com/O9i3xVGT0l

— Pablo Navarrete (@pablonav1) October 25, 2019

And a third, from a writer, producer & performer and “founder member of the influential electronic pop group, Ladytron“:

#Chile. 1.5 million on the streets of Santiago. At the very top is the flag of the Mapuche.

If this was a protest against a left-wing Government, or adversary of the US, and not the Neoliberal template for Latin America, this photo would be on the cover of every newspaper. pic.twitter.com/7wITHMn6Hu

— Daniel (@Daniel_IV_) October 26, 2019

You will note that all three videos have problems with provenance; we are not told where they come from or who made them when; all we can do is trust the account. Note also that each video makes an aware and accurate critique of “the media” (“curiously silent”). Marches for climate change, or against Brexit, Putin, or Trump get far better coverage. For some reason. But each video shows what any organizer of a street protest would regard as a success (policy outcomes or regime change or demands aside).

Here is a map showing street protests worldwide. Again, this is surely an enormous story, even the biggest story going, and the lack of coverage is, well, only to be expected:

(One might quarrel with the breakdown into “Economy/Corruption” vs. “Political Freedoms”; surely Chile’s protests, for example, have an aspect of political freedom, given Chile’s fascist past.) Here is a table, including (“GZero”) protests listed on the map above:

| Bloomberg (2019) | HRW (October 2019) | Gzero (as of 9/1/2019) | L.S. | |

| 1 | Algeria | |||

| 2 | Azerbaijan | Azerbaijan | ||

| 3 | Bolivia | |||

| 4 | Chile | Chile | Chile | Chile |

| 5 | Ecuador | Ecuador | Ecuador | |

| 6 | Egypt | Egypt | Egypt | |

| 7 | France | France | ||

| 8 | Guinea | |||

| 9 | Haiti | Haiti | ||

| 10 | Hong Kong | Hong Kong | Hong Kong | |

| 11 | Indonesia | Indonesia | Indonesia | |

| 12 | Iraq | Iraq | Iraq | Iraq |

| 13 | Lebanon | Lebanon | Lebanon | Lebanon |

| 14 | Libya | |||

| 15 | Netherlands | Netherlands | ||

| 16 | Peru | Peru | ||

| 17 | Russia | Russia | Russia | Russia |

| 18 | Spain | Spain | Spain | |

| 19 | Sudan | |||

| 20 | Uganda | |||

| 21 | Venezuela | |||

| 22 | Zimbabwe |

Once again, protests in 22 countries is rather a lot (and these, as it were, the wildfires, not small flare-ups here and there). But note that none of the sources (including me, “L.S.”) have a consistent list; it’s extraordinary that Bloomberg, which is an actual new gathering organization, omits Haiti, and that Human Rights Watch (HRW) omits France (since the state violence deployed against the gilet jaunes has been significant, far me so than Hong Kong).

So how are we to make sense of these protests? The Dean, we might call her, of studies in non-violent protest (and hence of the violence that accompanies or suppresses it) is Erica Chenoweth, so we will begin with her (I would classify her as an academic rather than an advocate, like Gene Sharp.) From there, we will broaden out to look at how the data that any academic — and, one would think, news-gathering organizations — would use. Finally, we’ll look at what the previous two academic approaches do not really consider: The social basis of protests as a predictor of success.

Non-Violence (Chenoweth)

Erica Chenweth begins “Trends in Nonviolent Resistance and State Response: Is Violence Towards Civilian-based Movements on the Rise?” (Global Responsibility to Protect[1], July 2017) with the following rather discouraging statement, at least if you’re a protester:

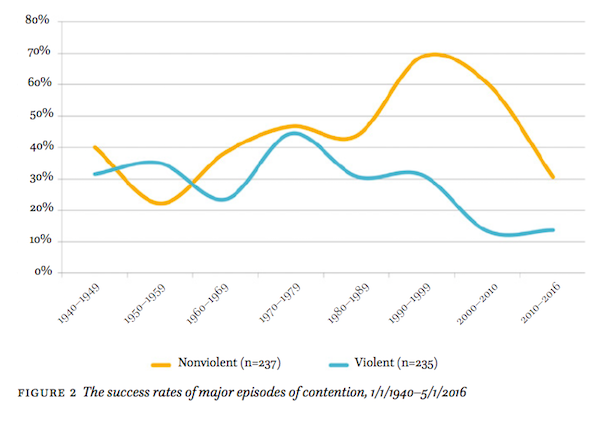

Through 2010, nonviolent mass movements tended to be surprisingly effective in removing incumbent leaders from power or achieving territorial independence, even when they experienced some repression from the government. However, since 2010, the success rates of nonviolent campaigns have declined by a staggering rate (about 20% below the average)

(Hence, any black-leather clad dude fetishizing “taking it to the streets” should be regarded with a hermeneutic of suspicion.) Here is her chart that showing the decline:

She speculates that the cause of the this decline is due to Authoritarian Adaptation:

the ability of authoritarian governments to adopt more politically savvy repressive tools may be part of the reason for the decline in success rates in the past six years.21. Authoritarian leaders have begun to develop and systematize sophisticated techniques to undermine and thwart nonviolent activists.

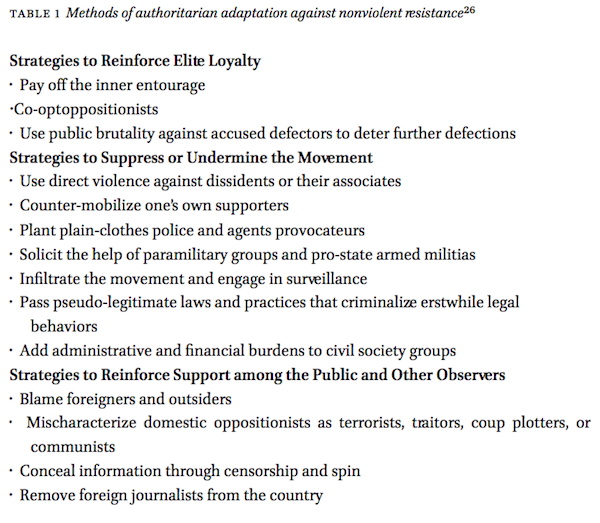

Chenoweth provides this table, categorizing these techniques:

Examining this table, and thinking back to Obama’s 17-city coordinated paramilitary suppression of Occupy, as well as his successful decapitation of Black Lives Matter, and moving to the McCarthyism and moral panics of the present day, as well as ICE, one might almost conclude that the U.S. has become an authoritarian state, instead of the flourishing republic it so obviously is. Be that as it may, if you want to look at the protesters, rather than the State, as the drivers, footnote 21 is very suggestive;

21. There may be several other reasons for this decline in effectiveness. First, because non-violent resistance has become such a popular and widespread practice, it is possible that those wielding it do not yet have the requisite skill sets to ensure victory. For example, Kurt Weyland has shown that radicals in various European capitals mobilized against their dynastic sovereigns with a sense of false optimism, having witnessed a successful revolution in France in February of 1848 (Kurt Weyland, ‘The Diffusion of Revolution: “1848” in Europe and Latin America,’ International Organization 63/3:391–423 (2009)). They essentially drew what Weyland calls “rash conclusions” about their own prospects for success and attempted to import the French revolutionary model into their own contexts, failing miserably. Second, a higher proportion of nonviolent uprisings since 2010 possess “violent flanks”—segments or groups within the campaign that destroy property, engage in street fighting, or use lethal violence alongside a predominantly nonviolent movement—than in previous decades. Violent flanks tend to undermine participation rates in nonviolent movements while discouraging security force defections (see Erica Chenoweth and Kurt Schock, ‘Do Contemporaneous Armed Challenges Affect the Out-comes of Mass Nonviolent Campaigns?’ Mobilization: An International Quarterly 20/4: 427–451 (2015)). Whereas the most successful decades of nonviolent resistance featured highly disciplined campaigns of nonviolent action, today almost 50% of primarily nonviolent campaigns possess some degree of violent activity from within….

Chenoweth’s strictures on “violent flanks” may apply to Hong Kong (though it is also true that the Hong Kong protesters have achieved their first goal, the withdrawal of the of the extradition bill). However, we should also remember the protester’s spray-painted slogan: “It was you who taught me that peaceful marches are useless.” We have yet to see. Perhaps practice has outrun the academics. Perhaps not. We will look at this issue more tomorrow; obviously, it applies to Chile.

Data Gathering (Fisher, et al.)

Chenoweth’s dataset of “major episodes of contention, 1/1/1900–5/1/2016” includes 237 non-violent and 235 violent cases. But if we seek to record and classify protests in near real time, there will be orders of magnitude more cases than that. Two projects to do just that are described by Dana R. Fisher, Kenneth T. Andrews, Neal Caren, Erica Chenoweth, Michael T. Heaney, Tommy Leung, L. Nathan Perkins, and Jeremy Pressman in “The science of contemporary street protest: New efforts in the United States” (Science Advances, October 23, 2019). This is a fascinating article, which I encourage all big data fans to read in full. From the abstract:

This article reviews the two most central methods for studying street protest on a large scale: building comprehensive event databases and conducting field surveys of participants at demonstrations.

Of event databases, they write:

Tracking protest events in real time is fundamentally a discovery and coding problem. It resembles the data collection components of past efforts to study protest by aggregating data from third-party sources (51, 54). Unique to today’s environment is the sheer number of sources and the time-limited nature of the discovery-and-review period: Given the transience of information on the internet compared to print media, thousands of sources produce reports of variable reliability on a daily basis. Researchers must archive and extract information such as where, when, and why a protest took place, as well as how many people attended, before that content is moved behind a paywall, deleted, or otherwise made unavailable.

(Encouragingly, the event database is a citizen science effort.) However:

these event-counting methods also have several reliability, coding, and discovery limitations and challenges, including (i) resolving discrepancies in reported data, such as crowd size, for the same event reported by multiple sources; (ii) evaluating the reliability and bias of each source; (iii) requiring manual review of what can be hundreds of potential protest reports every day; (iv) accurately and consistently coding events in near real time; and (v) having an incomplete list of sources and an incomplete list of reports from known sources.

Of field surveys, Fisher et al. write:

The complex environment of a protest leads researchers to focus their attention on several considerations that are not common in many other types of surveys. First, it is impossible to establish a sampling frame based on the population, as the investigator does not have a list of all people participating in an event; who participates in a protest is not known until the day of the event; and no census of participants exists. Working without this information, the investigator must find a way to elicit a random sample in the field during the event. Second, crowd conditions may affect the ability of the investigator to draw a sample. The ease or difficulty of sampling depends on whether the crowd is stationary or moving, whether it is sparse or dense, and the level of confrontation by participants. Stationary, sparse crowds that are peaceful and not engaged in confrontational tactics (such as civil disobedience, or more violent tactics, like throwing items at the police) tend to be more conducive to research. In general, the presence of police, counter-protesters, or violence by demonstrators are all likely to make it more difficult to collect a sample. Third and last, weather is an important factor. Weather conditions, such as rain, snow, or high temperatures, may interfere with the data collection process and the crowd’s willingness to participate in a survey.

The Women’s March after Trump was elected was one subject of surveys:

In her book American Resistance, Fisher examined seven of the largest protests in Washington, DC, associated with opposition to President Trump: the 2017 Women’s March, the March for Science, the People’s Climate March, the March for Racial Justice, the 2018 Women’s March, the March for Our Lives, and Families Belong Together (81). Her results… show that the Resistance was disproportionately female (at least 54%), highly educated (with more than 70% holding a bachelor’s degree), majority white (more than 62%), and had an average adult age of 38 to 49 years. Further, she found that the Resistance is almost entirely left-leaning in its political ideology (more than 85%). Resistance participants were motivated to march by a wide range of issues, with women’s rights, environmental protection, racial justice, immigration, and police brutality being among the more common motivations (83). She also found that participants did not limit their activism to marching in the streets, as more than half of the respondents had previously contacted an elected official and more than 40% had attended a town hall meeting

I think Thomas Frank would recognize “the Resistance,” although Fisher seems to have an odd concept of what “the left” might mean. For example, there’s no mention of strengthening unions, the minimum wage, or the power of billionaries, so I wonder what her coding practices were.

The authors conclude — as a good academic should do! — with a call for further research:

Moving forward, best practices will require forming teams of scholars that are geographically dispersed in a way that corresponds with the distribution of the events under investigation. While previous studies have concentrated on conducting surveys in different regions and in major cities, the datasets would be more representative if data were collected in multiple locations simultaneously in a way that represents smaller cities, suburbs, and rural areas.

Consider an event projected to take place in 300 cities simultaneously in the United States or Europe. Suppose that the target areas were stratified into 12 regions or countries. If a survey was conducted in three types of locations—one city, one suburb, and one rural site or one capital, one college town, and one urban area with neither a capital nor a university—in each region, that would require the survey to go into the field in 36 locations (or roughly 12% of events). Such a task would likely require a minimum of 12 to 36 scholars working together, each coordinating research teams to collect survey data at events in their region. Even more resources and institutionalization would be required to conduct crowd surveys at a genuine random sample of events.

Beyond collaboration among multiple scholars, scaling up the administration of surveys would also require standardization of the instrument, sampling, and practices in entering and coding the survey data.

Ironically, the scale of the effort to survey and record such an event — say, each scholar would have a team of 10, for a total of 360, would be within an order of magnitude or so of that required to organize it! (There were 24,000 Bolsheviks in 1917). What this article does show, however, is how blind the public and the press are flying (though doubtless the various organs of state security have better information.)

Class (Dahlum, et al.)

Finally, we arrive at Sirianne Dahlum, Carl Henrik Knutsen, and Tore Wig, “Who Revolts? Empirically Revisiting the Social Origins of Democracy” (The Journal of Politics, August 2019). They conclude:

We further develop the argument that opposition movements dominated by industrial workers or the urban middle classes have both the requisite motivation and capacity to bring about

democratization…. We clarify how and why the social composition of opposition movements affects democratization. We expect that both the urban middle classes and, especially, industrial workers have the requisite motivation and capacity to engender democratization, at least in fairly urban and industrialized societies.

Other social groups—even after mobilizing in opposition to the regime—often lack the capacity to sustain large-scale collective action or the motivation to pursue democracy. We collect data on the social composition of opposition movements to test these expectations, measuring degree of participation of six major social groups in about 200 antiregime campaigns globally from 1900 to 2006. Movements dominated by industrial workers or middle classes are more likely to yield democratization, particularly in fairly urbanized societies. Movements dominated by other groups, such as peasants or military personnel, are not conducive to democratization, even compared to situations without any opposition mobilization. When separating the groups, results are more robust for industrial worker campaigns

Why? Our old friend, “operational capacity“:

The capacities of protestors are found in their leverage and in their abilities to coordinate and maintain large-scale collective action. Leverage comes from the power resources that a group can draw on to inflict various costs on the autocratic regime and thus use to extract concessions, including political liberalization. Leverage can come from the ability to impose economic costs on the regime, through measures such as moving capital assets abroad or carrying out strikes in vital sectors. Other sources of leverage include access to weapons, manpower with relevant training, and militant ideologies that motivate recruits. Urban middle classes score high on leverage in many societies. Many urban professionals occupy inflection points in the economy, such as finance. Industrial workers can also hold a strategic stranglehold over the economy, being able to organize nationwide or localized strikes targeting key sources of revenue for the regime. In addition, workers often have fairly high military potential, due to military experience (e.g., under mass conscription) and, historically, often being related to revolutionary, sometimes violence-condoning, ideologies (Hobsbawm 1974).

Riots and uprisings are often fleeting, and opposition movements are therefore more frequent than regime changes. Hence, in addition to leverage, protestors must be able to organize and maintain large-scale collective action over time, also after an initial uprising, in order to challenge the regime. In this regard, groups with permanent, streamlined organizations can effectively transmit information, monitor participants, and disperse side payments. Organizations also help with recruiting new individuals, networking with foreign actors, and experimenting with and learning effective tactics. The urban middle classes have some potent assets in this regard, as they include members with high human capital, which might enhance organizational skills. Various civil society, student, and professional organizations can help mobilize at least parts of the middle classes. Industrial workers typically score very high on organizational capacity (see Collier 1999; Rueschemeyer et al. 1992). They are often organized in long-standing and comprehensive unions and labor parties and have extensive networks, including international labor organizations and the Socialist International. In sum, we expect opposition movements dominated by the middle classes or industrial workers to be related to subsequent democratization. Yet, we anticipate a clearer relationship for industrial worker campaigns, due to their multiple sources of leverage and especially strong organizational capacity allowing for effective and sustained challenges to the regime.

Lots to ponder here, including the effectiveness (or lack thereof) of a quintessentially “urban middle class” protest, the Women’s March, potential differences between Hong Kong and (say) Chile, and much much more — including the operational capacities of our own working class, and the effects of deindustrialization and gutting unions. I wonder of the condition of teeth, as a class marker, is included in any survey coding?

Conclusion

I hope this survey of the literature has been stimulating. I will have more to say about invididual protests tomorrow.

NOTES

[1] I’m super-uncomfortable with the “responsibility to protect” framing (which is why so much of the focus of the article is on state violence, presumably as a justification for the U.S. to intervene). That suggests to me that Chenoweth runs with the wrong crowd, at least part of the time.

Back in 2004 I had a few friends working in a film shot during the RNC convention protests. It made headlines because actress Rosario Dawson was arrested (police thought she was an anarchist protestor). The film shoot had footage of an undercover police officer posing as a protestor starting scuffles and trying to rile up other protestors.

It was written up in The NY Times but people still act as if this is crazed conspiracy talk.

Police Infiltrate Protests:

https://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/22/nyregion/police-infiltrate-protests-videotapes-show.html

Rosario Dawson Arrested:

https://ew.com/article/2004/08/30/rosario-dawson-arrested-gop-convention-protest/

Thanks for this.

Of interest is the underlying assumption in the Conclusion of your post; that pre-existing exposure to sub-national group organizing is positive towards successful outcomes. In most situations, a Union is organized against strong countervailing pressures from the Owner class. A winnowing out process that concentrates and toughens successful organizers has already occurred. As it were, protests that draw on extant Union personnel have an automatic advantage. An entire step in the organization formation process has been rendered irrelevant. Access to “off the shelf” organizers will jump start a movement.

As a corollary to the above, I note the absence of an even semi-professional class of agitators in the United States. Not so do I note an absence of outright professional Organs of the State: Oppressors.

A century ago, the world had several international organizations seriously dedicated to the subversion and overthrow of “Free Market” Capitalism. Today?

True, and that complicates the studies Lambert cites in at least two ways.

1. In what Lambert reports, and I think he’s got the drift of their arguments, the distinction between violent and nonviolent movements ignores the way in which nonviolent movements have deployed the threat of violence precisely by offering themselves as a nonviolent alternative. Within the Civil Rights movement in this country “if you don’t listent to us, you’ll get them” was part of King’s message to white elites, with “them” referring to everyone from Malcolm X to the revolutionary elements of international Marxism. Others with a better understanding of India’s independence movement could find a parallel.

2. Running in the opposite direction, international movements, particularly on the left, have often been a brake on local initiative. The Trotskyist critique of Stalinist practice, wherein the Stalinist international imposed, often murderously, controls on national communist parties to avoid (overly) antagonizing the bourgeois international, is at least historically accurate, however much one might dispute its strategic validity. This isn’t so immediately relevant to the violent/nonviolent question, but it does help foreground the international context that the summarized articles appear to lose track of.

Especially due to (1) the data behind the graph needs a good review for ‘interactive effects’ of this sort.

“Oh, they’re rioting in Africa

They’re starving in Spain

They’re purging in Bosnia

And Texas needs rain…”

Does anyone else remember the Kingston Trio’s “Merry Little Minuet”?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JVUh5OaiADc

3 weeks ago I witnessed a large protest on the streets of Seoul, I’d think at least 50,000 people. But it was mostly elderly folk and very right wing, essentially protesting at what they see as Government policies that are too pro Chinese and pro North Korean. The protests were clearly well financed and organized – the banners were mass produced and ‘non-official’ ones were almost all pushed to the fringes. Locals were contemptuous, saying they’d all been paid to turn up and bussed in from the provinces. There were smaller protests on other days. All were peaceful.

I also saw the aftermath of a very big protest in Hong Kong A few days before. There was a lot less damage than you’d think from the international reporting, a few shops burnt out. But I was left with little doubt that there was a lot of ‘silent’ support among regular HKers and even ethnic Chinese (mainlanders) for the protests.

The winners write history. Surviving losers also rewrite history (‘Gone with the Wind”). Or, past lives are never written about at all. The problem is that western government has swirled down the drain into incompetent delusion. Corporations rule. Plutocrats are in combat over the spoils. Protests won’t work until police and mercenaries realized that they aren’t being paid enough to die or to subjugate their own families.

Right now, the problem is two million Californians forced out of their homes or waiting with no electricity for evacuation orders. The American government is simply incapable rebuilding Puerto Rico or Northern California. Or handling global plagues such as African Swine Fever that has already killed a quarter of the global pig population. Simply put, climate change, overpopulation, and rising inequality assure that revolutions cannot be orderly.

The 10% Technocrats like Elizabeth Warren will try to keep things running until they can’t anymore.

> The American government is simply incapable of rebuilding Puerto Rico or Northern California.

American elites are resolutely opposed to

simply incapable ofrebuilding Puerto Rico or Northern California.Fixed it for ya…

Does the administrative capability still exist? When we talk about “3rd World,” we’re saying it doesn’t.

So, can PGE or PERS be fixed?

“operational capacity“ – yes, that’s the term I wanted.

Sorry, what is “adaption” in the title?

A typo!

I don’t see how the protests in Spain by Catalan nationalists are a case of political freedom.

If you believe that the right of self determination means that countries like Spain are divisible, then why not also allow Catalonia to also be divisible? And let people in every city, town, street, and house be able to decide which country they want to split off or join?

I would have complete sympathy if Catalans were protesting against any legitimate oppression regarding their language or culture, or any other related discrimination. Why don’t more Catalans simple work with others in Spain and the EU to make it more equal, fair, and just, than give in to racist nationalism?

The modern world simply cannot afford to allow nationists to split up the world into smaller pieces, which often leads to wars, ethnic cleansing, and additional oppression of any remaining “non-pure” people.

This is a good question for which the stupidity of brainless nationalism has no answer (nationalism musn’t be brainless but too often it is). In reality this is more an struggle for political power rather than fight for rights. And of course, although less noisy, there are many catalans that don’t give a damn on independence. Only, or as many as, 42% of catalans ask for a referendum on independence but a larger majority prefers negotiations on autonomy.

One would think that brexit is a good example of what could go wrong on badly thougth procedures of independence but blind nationalism, always believes in its exceptionality. You can compare the Torras and Puigdemont of the moment as illuminated as Jonhson or Blair in their own moments: feeling incapable of wrong doing and above procedure rules. A recipe for disaster if they ever prevail.

Not to mention those grandiose catalan leaders are as neoliberals as any other counterpart of its class around the world.

As an example we have Mr. Utility Friendly Torras, current president of the Generalitat, going his way on energy policy and giving still validity in Catalonia to an anachronic decree approved in Spain by his co-religionary Rajoy (but hated because, you know, spanish) in 2009 –and now derogued– that was a stop signal for the development of renewables. This occurs even when the Parliament od Catalonia has already repealed the decree. Shows the kind of respect this great leader has for procedures when anything does not align with his ideas.

I think that riots in Gaza are going to have to added into that data set-

https://news.antiwar.com/2019/10/27/95-demonstrators-injured-in-gaza-protests/

It would come under the category of ‘Political freedoms’

> It would come under the category of ‘Political freedoms’

I don’t know if I accept those categories, though.

If Gazans wanted political freedom, they’d be rioting against Hamas, which has refused to hold general elections for eight years and kills its political opponents and civilians who object to their policies. What they really want is dead Jews.

The Gazans are in a tough spot. The surrounding states view the Gazan situation as a spur in the flank of Israel. The constant threat of the descendants of those Arabs ‘ethnically cleansed’ out of the whole of Palestine in 1947 being sent into Israel to reclaim their ancestral lands is a constant in the Arab state’s permanent conflict with the State of Israel.

The alternative offered to the Gazans is to become permanent second class citizens in a Greater Israel. Actually, make that third class citizens. At present, Israel has First Class, comprised of the Orthodox religious Jews, Second Class, comprising the Secular Jews, and Third Class, all others.

As for self rule, with a dollop of actual democracy, well, easier said than done.

” Violent flanks tend to undermine participation rates in nonviolent movements while discouraging security force defections”

Ecuador and Chile pose a challenge to that theory. The events there are significant in themselves, because traditionally, capturing the capital constitutes victory, whether a revolution or an invasion. In Ecuador, that was clearcut: the demonstrators – not very non-violent – controlled the capital and drove the government out of it, then continued a rampage against government buildings. The president, from Guayaquil, ordered the military to remove them – which didn’t happen, probably for ethnic reasons. As before, this was essentially an Indian uprising. Moreno caved, which means he can’t meet his agreement with the IMF. This was the IMF riot to end all. And we were just talking about retiring in Ecuador.

In Chile, more than a million people in the street have essentially captured the capital, as the videos make clear. Nothing is going to move, short of extreme violence. Again, the president capitulated and undertook to meet the demonstrators’ demands. That one wasn’t really non-violent, either, though the culminating demonstration was.

In both cases, victory is somewhat qualified because the right-wing president remains; the real result remains to be seen – but notice has been served. If that process continued much further, he could be lynched in the street. (I do wonder why Chile re-elected a right-winger, only a year ago. They now have to reverse an election.)

And looking at the map: the US isn’t there. A hyper-violent police force alienated from the public might be a factor.

> Ecuador and Chile pose a challenge to that theory

I think Chenoweth’s perspective could be a bit US-centric, or academic-centric. I have to admit that one reason I agreed with her is that the black bloc’s role in Occupy was so pernicious (with “diversity of tactics” being on a par with “innovation” and “sharing” for seamy tendentiousness). I think in the United States we are not ready, as it were, for “violent flanks.”

So when I started following Hong Kong, I viewed matters at first through the Occupy Frame (and the black-clad protesters didn’t help me avoid that). However, it’s clear that a substantial portion of the population really does see then as “front-liners,” as in America we would not. Further, property violence seems carefully calibrated, as in the United States it is not. So I was wrong.

It depends…

…Possibly an area for contemplation: Where are the protests NOT…and WHY???

See under “operational capacity.” Another consequence of deindustrialization and union-busting. So, new tactics and strategies required…

Thanks, Lambert; I get that…Here; in the U.S. it is *divide and conquer*…, or conquering by division…as long as we fight with each other over *hot button* topics; we can’t get together to deal with the big; underlying issues.

…”who’s side are YOU on, anyway???

(rhetorical question)(not aimed at Lambert!!!)

There’s another kind of protest entierely; the entiely fabricated protest as means of pro-establishment propaganda. Here in Portland, OR, we’ve been treated to some breathlessly sensationalized street battles between ostensibly far right and far left ‘protesters’. Eyewitness accounts speak of supposed ultra-conservative activists popping out of the back of police vans to instigate dustups. And anyone who’s not wholly ignorant of the infiltration of left activists in the 60s knows just how easy this is. A Punch and Judy show managed from FBI headquarters which is then reported by hyperventilating media. Fox News shows us raggedy Bolsheviks with bandito massks beating up clean cut journo Andy Ngo (who then goes on the pro-Israel circuit after recovering from massive brain trauma!) Then switching to Amy Goodman, you get bald thuggish looking white guys with tattoos variously of Christian and Viking themes (how exactly these really mesh in anyone’s mind, I don’t quite get-but that’s supposing it’s real) forming a phalanx and waving confederate flags.

The entire thing seems fabricated to push fretting liberal homeowners and Responsible People to support the ‘radical center’ of neoliberal Clintonism.

Since you live in Rose City, feel free to go on down and meet the “raggedy Bolsheviks” for your own self. Or talk to the nazis, most are friendly enough to ‘non-combatants’.

No doubt there are false flaggers and cops in both groups, but I assure you the conflict itself is not staged.

Thanks for starting to wade into this topic. I appreciate the academic sideboards as a way to discover the common elements. Which will help us with the revolution against neoliberalism here in the US.

let me add my thanks for this round up. I look forward to continuing coverage on this topic and especially beg those living outside the US, most especially those speaking the local languages to give us the benefit of your observations.

a bold peace is a film about Costa Rica’s path to demilitarization

http://aboldpeace.com/

somewhat related,

John Perkins Confessions of an Economic Hit Man Full audiobook

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ySefPIZaYT0&t=3160s

Marcie Smith has done amazing research into the “guru of nonviolent revolution,” Gene Sharp, who turns out to be a CIA tool responsible for the “nonviolent” color revolutions which were just an easier assertion of soft power than those annoying invasions and coups.

So amazing that you can’t be bothered to supply readers with the link? Here is it is. I think Smith oversimplifies; I also think misuse of Smith’s work leads to a quasi-religious tendency (“faith is the evidence of things not seen”) to imagine CIA agents behind every protest sign, and to imagine Sharp as a Saruman-like figure controlling the action from a distance, all of which is both untrue and demoralizing/disempowering. You also seem to think that Sharp’s techniques substitute for invasions and coups; but in Serbia they clearly did not, since we had both Otpor and bombing; and in Tahrir Square, to the extent that Sharp inspired that protest — the hashtag #GeneSharpTaughtMe was widely used at the time, in mockery — an invasion wasn’t even an option. It’s also not clear that the outcome of Tahrir Square was an outcome we even desired; clearly the protesters had no idea what to do with power if they won, which one would think their case officers would have handled as a matter of course.

The reflexiv sequence protest -> color revolution -> Gene Sharp -> CIA seems deeply attractive to some soi disant leftists; it’s so mechanical and pointless and self-defeating it makes head hurt and my back teeth itch. (Even at the best, it’s like arguing that because the Germans sent Lenin over the Russian border in a sealed train in 1917, that the Bolsheviks were all a plot by Kaiser Wilhelm II.)

I’m also curious why you even bring up Gene Sharp. The post doesn’t mention him. Is it your thesis that the CIA is behind all the global protests?

This is a good point.

Not all opposition is controlled, but that does not mean the forces of the ancien regime don’t try. The upheavals in Egypt caught the neoliberal paladins by surprise and caused much dismay. That the Army brought the mild islamist party leader down in a counter-doup is not a symptom that the entirety of the Tahrir Square enterprise was a CIA orchestrated hoax of some kind. Just that the US was happy to let Morsi hang once the Generals got their act together. There certainly are many pro neoliberal coups that dress themselves up in liberatory clothing. (Maidan and Georgia are the claerest examples.)

Gene Sharp, from everything I’ve seen on him and his career, showed him to be a true believer in neoliberalism and the empire that propped it up. I suggest people look into his views on the “free market,” and its relation to democracy, to see what he was really about.

What was the name of the institute he headed over at Harvard for so many years? Why, it was the “Center for International Affairs”! Now why did they decide to rename that, after waves of student protests against it? The acronym just a little too “on the nose?” He seemed like a willfully ignorant dupe working alongside a long list of cold war psychopaths. Whether or not he “believed” this or that, about his own work, is irrelevant.

How did housing costs soar during the Great Moderation?

They tweaked the stats. so that housing costs weren’t fully represented in the inflation stats.

Everyone needs housing, and housing costs are a major factor in the cost of living.

Countries are suddenly erupting into mass protests, e.g. France and Chile, and neoliberalism is a global ideology.

What is going on?

Disposable income = wages – (taxes + the cost of living)

They cut taxes, but let the cost of living soar, so people got worse off, as the millennials are only too painfully aware.

They have created artificially low inflations stats. so people don’t realise wages and benefits aren’t keeping pace with inflation.

https://ftalphaville-cdn.ft.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Perfect-Storm-LR.pdf

Part 4 : Loaded Dice

This is a time bomb waiting to explode.

It’s already gone off in France and Chile and is waiting to detonate somewhere near you.

If you keep infaltion stats. down it reduces the cost of benefits.

In the UK we have two numbers for inflation.

RPI – the high number

CPI – the low number

We use CPI to track wages and index benefits.

We use RPI to index link bond payments to the wealthy and as a base for interest on student loans.

It’s all very neoliberal.

How tight is the US labour market?

U3 – Pretty tight (the one the FED use)

U6 – A bit of slack

Labour participation rate – where did all those unemployed people come from?

Not to mention the underemployed — the ongoing commitment of western regimes to inflation prevention at the expense of labor wastage and the consequent immiseration of the citizenry is scandalous.

Those neoliberals strike again.

The minimum wage is specified at an hourly rate, so a part time job doesn’t pay a living wage.

That’s an interesting link. Thanks!

It has always amazed me that economists wonder “Why did we get so smart around the 1700s? Growth world wide had been stagnant for a thousand years…..”

I’ve always tried to yell “BECAUSE WE DISCOVERED FOSSIL FUELS, YOU MORONS!!!!”

Kenneth Pomeranz’s “The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy,” basically proves your point very effectively. Pretty much beats down any crypto-racist theories on the superiority of “western civilization,” etc. China didn’t have coal, simple as that.

I would say that one has to categorize “protests” in order to uncover how they relate to social relations of power. Violent vs non-violent framing is useful if you want to argue that violence is not just immoral but actually impractical. If you want to try to prove the eternal moral basis of the liberal order, it’s great. If you really want to uncover how conflict and power work, you need more vectors.

Complicate Chenoweth’s liberal framing by adding more categories. What’s the goal of the movement? Is it revolutionary of reformist? Is the movement organized or diffuse? If the violence is diffused is it lumpen rioting and random terror? If the violence is organized is it terror cells, military columns, foreign invasion or something else? If the movement is organized non-violent, does it exist at the same time as an organized violent movement with similar goals? If the movement is organized non-violent, are the people in it armed but not using the arms? If the movement is diffused non-violent is it actively opposed to violence? Every combination matters in context, and the reform vs revolutionary labels absolutely matter. There is a big difference between demanding the end of a fuel tax and demanding the end of capitalism. There is a big difference between the treatment of armed people and unarmed people by security forces, depending on the context.

In general IMO, reforms under liberalism can be captured through non-violent protest, and diffused violence can harm their chances because they give security forces an excuse for a crackdown. The organized threat of violence can help organized non-violent reform protests because it scares the ruling class (BPP in the USA is a great example), but organized violence itself can harm non-violent reform protests unless it’s successfully revolutionary. Revolution (not just a change in government!) can never be achieved through non-violent protest, because the ruling class will use violence to save themselves.