This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 366 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year and our current goal, funding meetups and travel.

Yves here. We’ve linked to articles on rural hospital closures, but this overview makes clear how widespread and serious this problem is.

By Jane Bolin, Professor of Health Policy + Management, Deputy Director of the Southwest Rural Health Research Center; Associate dean of research, College of Nursing, Texas A&M University, Bree Watzak, Clinical assistant professor, pharmacy, Texas A&M University, and Nancy Dickey, Professor, Executive Director, Texas A&M Rural and Community Health Initiative, Texas A&M University. Originally published at The Conversation

Presidential candidates and other politicians have talked about the rural health crisis in the U.S., but they are not telling rural Americans anything new. Rural Americans know all too well what it feels like to have no hospital and emergency care when they break a leg, go into early labor, or have progressive chronic diseases, such as diabetes and congestive heart failure.

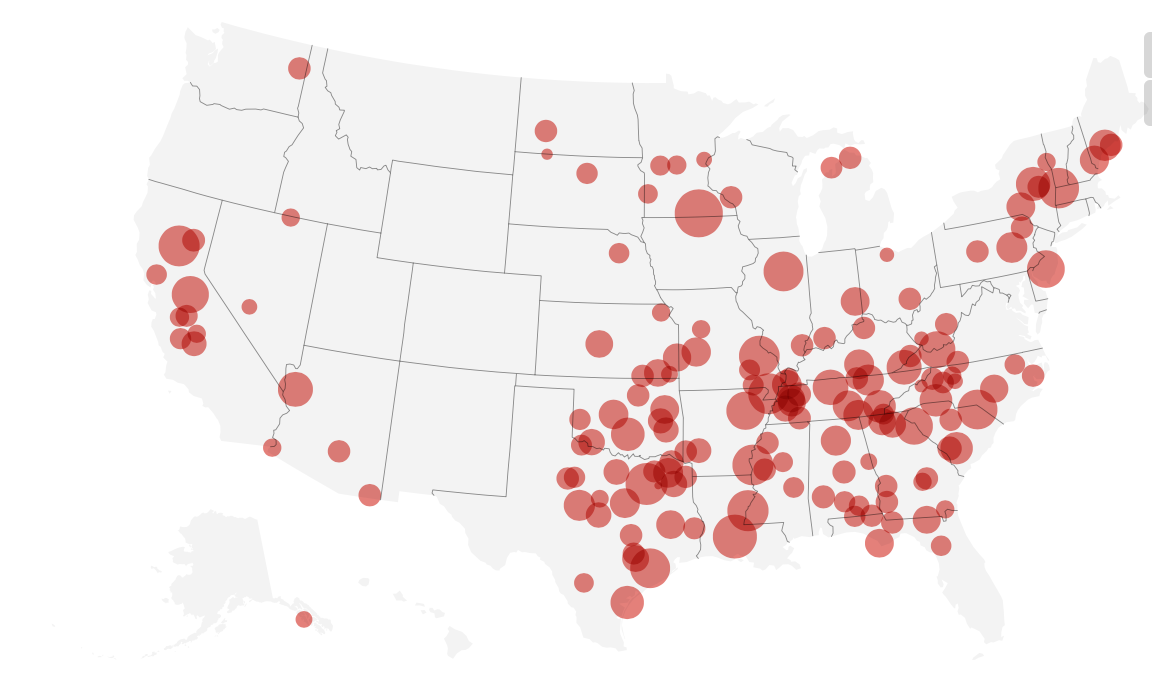

More than 20% of our nation’s rural hospitals, or 430 hospitals across 43 states, are near collapse. This is despite the fact that rural hospitals are not only crucial for health care but also survival of their small rural communities. Since 2010, 113 rural hospitals across the country have closed, with 18% being in Texas, where we live.

About 41% of rural hospitals nationally operate at a negative margin, meaning they lose more money than they earn from operations. Texas and Mississippi had the highest number of economically vulnerable facilities, according to a national health care finance report in 2016.

As rural health researchers, we’re well aware of the scope of rural hospitals woes’, which span the entire country. Struggling rural hospitals reflect some of the problems with the U.S. health care system overall, in that the poor often struggle to have access to care and there are few obvious solutions to controlling rising costs.

If 20% of America lives in a rural county, why is the nation so slow to address rural health disparities?

There Goes the Hospital, and the Town

Each time a rural hospital closes, there are tragic consequences for the local community and surrounding counties. While the medical consequences are the most obvious, there is also loss of sales tax revenue, reduction in supporting businesses such as pharmacies and clinics. There are also fewer professionals, including doctors, nurses and pharmacists, and fewer students in local schools.

The closing of a rural hospital often signals the beginning of progressive decline and deterioration of small rural towns and counties. Hospitals often serve as financial and professional anchors as well as source of pride for its small rural community. It also often means loss of other employers or inability to recruit new employers due to lack of nearby health care. When a rural hospital closes its doors, unemployment often rises, and average income drops.

There are no nurses, doctors, pharmacists or ERs for local farmers, ranchers, growers and assorted men, women and children who love living and working in America’s vast rural regions. Rural communities and rural citizens are often left with no options for routine primary care, maternity care or emergency care. Even basic medical supplies are often hard to find.

Residents in these communities have had to take their chances living in America’s heartland, finding alternative options for basic health care services.

A Compound Fracturing

Those rural hospitals that have remained open are facing increasing legislative, regulatory and fiscal challenges. Some policy analysts have noted that the states with the most closings have been in states that did not expand Medicaid.

And, many of the towns in which they are located suffer from an apparent leadership vacuum. There are typically few experts within small towns who are prepared to address ways to avoid the loss of rural health care services and rural hospitals.

Small, rural communities are also less likely to have conducted formal comprehensive health needs assessments or invested in strategic planning to strengthen the ability of the community to adapt more quickly to changes in the local economy as well as changes in financing health care at the federal level. Health care services planning is often limited to input from the rural community leaders and “power brokers” rather than a cross-section of the greater community.

For example, community leaders may want to have an orthopedic surgery option, but if they had input from the community, they would know that prenatal/maternity care was more of a priority and these patients don’t have transportation so they also need a bus or van to pick up for appointments.

There are also cross-cutting rural community challenges such as:

- Declining reimbursement levels

- Shrinking rural populations

- Health professionals moving to bigger cities for higher compensation

- Increasing percentage of uninsured leading to rising uncompensated care

- Increasing operating costs

- Older and sicker rural dwellers with complex multi-system chronic diseases.

The result is that rural hospitals often lack a dependable economic base to operate. In addition, changing processes, payment strategies and regulations coming from state and federal regulators place the small rural facility at particular risk because keeping up with changing payment or reporting rules often requires a full time person.

The continuing closures have accelerated the urgency to understand and address the problems faced by rural Americans seeking access to care. Each rural region of the country has its own industry, economy, cultures and belief systems. Therefore, rural solutions will be unique and not an urban solution downsized to a smaller population.

Replacing the Hospital With … What?

At Texas A&M Health Science Center, we are among several researchers focused on rural disparities by researching causes of socio-economic inequities and by working within those rural communities to “give a leg up” to distressed rural communities and counties nationally, and in Texas.

We’ve come to see that providing health care services in rural counties may not include maintaining a full-service hospital, but rather “right-sizing” care to match the resources, demographics, geography and availability of providers in the community.

For example, the ARCHI Center for Optimizing Rural Health is currently working with hospitals and their communities to determine feasible health care options that will be supported by the community, meet community needs, and most importantly, offer local, high-quality care. Using tools like ARCHI’s DASH – a quarterly dashboard that shows performance of the hospital in financial, quality and patient satisfaction arenas – may help hospital boards, communities and local leaders better understand their status and need for change from business as usual.

While it may be that the changing health care delivery systems are altering what health care delivery looks like, change can almost never be instant. Communities may need to envision alternatives to hospitals.

In some communities, urgent care with radiology and lab services may be able to service the majority of health care needs. In other communities, a “micro-hospital” with an ER and swing bed options – which allow rural hospitals to continue to treat patients who need long-term care or rehabilitation – may be the better fit. Telehealth, or providing care through televideo virtual face-to-face from remote sites to rural residents, can also be an option.

Challenges specific to the dilemma of rural hospital closure will take a national, state and local effort focused on the plight of rural communities struggling to maintain availability of essential health care services. Our nation’s vulnerable rural communities deserve a focused, coordinated effort to address this compelling problem before any more rural hospitals close their doors.

This article is part of a collaborative project, Seeking a Cure: The quest to save rural hospitals, led by IowaWatch and the Institute for Nonprofit News, with additional support from the Solutions Journalism Network.

Looks like my state, Texas, is out in front again! I guess being number one in air pollution, the death penalty, and teen pregnancy wasn’t enough.

But you’ve got Freedom! You don’t allow any of that Socialism in Texas! (/sarc, if it wasn’t obvious)

There is a large billboard on the way from San Antonio to Austin with a blue California and a red Texas.

The caption:

California — too late

Texas — still great

Vote Republican

I’ve never seen more pawn shops, than in the loan star state, but when you need to borrow $50 on your 55 inch HD TV, they’re there for you.

Yeah, and just try and buy something from one of those places at less than 110% of retail. It can be done, but you have to wear a mask and carry a gun to do it.

I see this in the high-acuity, big-city hospital that I work in. People with bowel obstruction, that’s not rocket science to surgically repair, but smaller hospitals airlift them to Seattle. Also, pregnant women with probable fetal demise: at a time when they need family & kin close at hand, they’re off to Seattle. Also, elderly with broken bones from falls: this is the most recent uptick I’ve seen. Again, they get get airlifted away from their social support system. All of these things were treatable at rural hospitals until recently.

No worries, if you have an emergency, there’s always that $50k helicopter ride to rush you to the city.

What is the role of the ever-increasing (and with an increasing percentage being corporate-owned) ‘urgent care’ facilities that have been springing up around the country? I have used them a couple of times when I needed care for a condition that was not life-threatening (a toe that had lost a battle with the sharp edge of a restaurant’s metal door, an insect bite that resulted in a ballooning hand, a replacement for lost meds on a vacation trip). Great care and no waiting. And …. they take Medicare! Or course, the night I had a bad reaction to a prescription drug I was taking and suspected a stroke, I headed for the local hospital.

We were in Syracuse NY for the weekend; it had been years since our last visit (a drive-through) and the city is showing some revitalization … on the surface (the homeless population has been swept away to the fringes on the other side of the interstate that cuts though down-town). Upstate Medical Center and SUNY Medical School seems to be a large part of the ‘economic engine,’ along with Syracuse University. All the buses had medically-themed advertisements …. breast-cancer centers, joint replacements, etc. And, my favorite … “If you have a stroke or heart-attack, tell them ‘Take me to Crouse!'” Is the concentration of hospitals and medical care in larger cities (the same thing seems to be happening in Pittsburg) sucking the life out of the smaller, local care facilities?

We have a clinic in our little town of 2,000 and it fills the same needs for me, a tweaked knee, a tick bite that requires me to go on 10 days of antibiotics, that sort of thing.

The hospital in Visalia-the nearest big city of 138k is named Kaweah Delta, some friends of mine call it ‘Killer Delta’ on account of not the best medical help you ever saw, and the hospital in Tulare got closed down about a year ago, and reopened under a new name, not a confidence builder, that.

The ads mean that there is too much money sloshing around in their business. The more efficient industries have way fewer ads but they are more targeted unless they are selling beer.

Upstate NY cities are the least likely to have their real estate prices tank in the next recession (that is what we say in the 2003-2009 period as well – prices barely moved up or down). They didn’t analyze Syracuse but Buffalo and Rochester have similar economies. The big companies left town decades ago so the employment structure is now much more diverse and much less dependent on large employers, although SU, Upstate Hospital, Crouse Hospital, and St. Joe’s are all major players. All of those are within about 1 sq mi. which is an indicator of how concentrated competing hospitals are in the US. In Canada, the focus is on having fewer hospitals further apart. https://www.redfin.com/blog/next-recession-housing-market/

Urgent Care facilities, and their more-expensive cousins, the Stand-alone Emergency Rooms, were created by the Affordable Care Act and regulations that allow Big Healthcare to charge more for the same services that are provided by GPs in other areas. The corporations love them—find some struggling doc who didn’t make it into the specialization guild, and pay them a moderate fee to treat mild medical conditions, but charge the customers and insurance companies more. It’s a cash machine, which is why there are so many of them.

Dinosaur barbecue is pretty good in Syracuse also. As to hospitals? What you are seeing is the rise of the ACOs.

So we’ve had decades of utterly ineffectual hand wringing over deindustrialization and decaying infrastructure and I suspect we’re now in for decades of the same about the denial of urgent medical care across vast stretches of the country.

As you guys say, everything is going according to plan.

…but, can I keep my insurance company?

Saskatchewan is the birthplace of single-payer healthcare in North America. Because of this, Tommy Douglas (premier of the province who pushed it @ 1960) was voted the greatest Canadian a few years ago.

Saskatchewan’s population is 1.2 million people spread over an area the size of Texas (Texas is 28 million people – almost as many people as all of Canada). The largest city is 250,000 people. If you want a model for rural medicine, this is the place to look.

Here is their business plan to provide healthcare to every resident of Saskatchewan: https://www.saskhealthauthority.ca/about/Documents/2019-20-SHA-Business-Plan.pdf

pp. 38-39 of the pdf show statistics for the different types of hospitals etc. and usage statistics. The system is well organized with different types of facilities for different locales. Ambulance usage is viewed as part of the healthcare system to reduce the need for expensive facilities. So no balance billing for out-of-network ambulance rides and physicians.

BTW – this is the type of place that Trump wants to import drugs into the US from to be cost-effective.

It is possible to do a good job on rural medicine. Just not in the US because there is no profit in it – just the well-being of people.

Saskatchewan cowboy singer Colter Wall wasn’t ruined by socialism. Maybe single payer advocates could ask him to do a song on health care on the range.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=MmxKsK90L14

Should I see also the hand of private equity at work here, ensuring themselves yet more “out of network” charges?

I live in one of those small town rural counties. By no means typical because our second home owners and golf courses have grown to equal grain and potato farming in the economy of the county. We have a fairly well equipped hospital, an EVAC helicopter, and doctors working in hospital-owned clinics and in private practices.

Last year I decided to have surgery on a heel bone spur that had gradually grown larger over time. The orthopedic surgeon connected to the local hospital examined it and quoted an estimated $22,000 to remove it. (a 30 minute procedure) Even though Medicare was covering 90% of the cost that seemed rather high. I ended up having it done in a large regional hospital by a top level surgeon. Cost? $3,700 including an overnight hospital stay!

Come to find out, Medicare assigns a special category to hospitals who are careful to provide less than 20 beds. They can charge any fee they choose, supposedly to compensate for the “service” they provide to their small communities!

By the way, the one surgeon practicing at the local hospital drives a new $100,000 Tesla.

The median annual heath care cost for a family of 4 in the USA just edged over $20,000.

Cuban per capital health care cost is 5% of that in the USA with a similar outcome, except that Cuban longevity is substantially longer and child mortality lower.

I previously lived in an area where one of those rural hospitals may shut down. After two major employers left it’s been a steady yearly drop in population and an inverse of demographics data that reflect the losses.

Stabilize and transport is our Government’s solution for rural health care. Expanding Medicaid is not the solution. States can’t print money like the federal government. The Government is the problem with increasing health care costs by insane regulations/standards/best business practices our un-elected bureaucrats within Centers Medicare Medicaid Services (CMS) impose on our health care providers. If you really want to see why health care costs are so high, explore how CMS establishes Medicare Reimbursement Rates through their reimbursement panel participants.

CMS needs to be more transparent to the citizens they serve in the United States of America.

Stabilize and transport is a key to the Canadian model as well. The big difference there is that it is deliberate and budgeted for. People that are part of the healthcare system (almost everybody) don’t pick up the tab for the stabilize and transport part, even by plane or helicopter because the system views it as cheaper than maintaining a large expensive facility in that vicinity. Major urban hospitals are a hub of helicopter activity as rural and wilderness patients get airlifted in for emergency treatment.

It’s an old story. The current Canadian system started out on the high plains to address rural health care issues. And in the county where I was prosecutor, both hospitals are owned by public hospital districts, and one of them had to buy out the local medical clinic to make sure it had physicians because the clinic could not lure new doctors in to replace the ones who were retiring.