Lambert here: Of course, in this country we have private equity. So there’s that.

By Litterio Mirenda, Economist, Bank of Italy, Sauro Mocetti, Senior Economist, DG for Economics, Statistics and Research, Bank of Italy, and Lucia Rizzica, Economist, Bank of Italy. Originally published at Vox EU.

The expansion of organised crime generates losses in economic growth and social welfare. This column estimates the impact of mafia penetration in the legal economy in Italy, looking both at the micro-level effects on firms infiltrated by ‘ndrangheta members and at the more aggregate long-run effects on local economic growth. It finds that infiltrated firms are disproportionately in the utilities and financial services sectors and that infiltration has a strong negative effect on local long-term employment growth.

The proceeds generated by organised crime in illicit markets are estimated to amount to about 2% to 5% of global GDP (UNODC 2011). However, the presence and activities of criminal organisations are not limited to such markets but have progressively spread into legitimate businesses, where they benefit from a competitive advantage thanks to the availability of illegal capital and their coercive and corruptive power. The resulting market distortions can impose a loss on society as a whole in terms of long-run economic growth (Pinotti 2015, Acemoglu et al. 2019).

In a recent paper (Mirenda et al. 2019), we analyse the effects of mafia spread outside its areas of origin and into legitimate businesses. Specifically, we focus on the ‘ndrangheta, a major criminal organisation originating from the south of Italy, and analyse its penetration in the centre and north of Italy, areas with no tradition of mafia settlements.

Our choice of the ‘ndrangheta is supported by two core characteristics of this organisation: (i) its tight family structure, i.e. the fact that affiliation to clans is systematically determined on the basis of family ties with very rare cases of mobsters not belonging to the boss’s family; and (ii) its strong tendency to export its activities outside the territory of original settlement, i.e. the region of Calabria.

The Penetration of the ‘Ndrangheta in Northern Italy

Our analysis starts with the construction of a proxy indicator for ‘ndrangheta infiltrations into firms by combining the data on a firm’s governance structure with information recovered from investigative records. In particular, we identify all firms in which, in a given year, there is at least one owner or director who (i) carries a last name that is among those listed in a national anti-mafia commission report as belonging to ‘ndrangheta families active in the centre and north of Italy (Dalla Chiesa et al. 2014) and (ii) is born in the area of origin of the ‘ndrangheta. Whenever these two conditions are jointly met for at least one owner or director, we classify the firm as likely to be infiltrated (hereby ‘infiltrated’) from that given year onwards.

The resulting picture is one in which about 1% of the firms in the centre and north are classified as infiltrated, with yet significant heterogeneities both across geographical areas and across sectors of activity.

With respect to geographical areas, the highest concentration of infiltrated firms is found in the northwest of the country, areas in which, indeed, the presence of the ‘ndrangheta has been most documented (Transcrime 2015).

Most of the infiltrated firms operate in the construction sector (19%), followed by real estate (15%), and wholesale and retail trade (11%). Looking at the odds ratios, the infiltrated firms appear to be overrepresented in the sector of utilities (e.g. electricity, gas or water provision, and waste disposal) and financial services (e.g. money transfers). All these are either activities that rely more heavily on public demand (e.g. construction and utilities) or that are more suitable for money laundering (e.g. retail or financial services). The sectoral distribution we trace closely mirrors that of the firms that have been seized by the Italian judiciary from criminal organisations from the 1980s.

When considering the balance-sheet data of infiltrated firms in the years preceding the infiltration, we find that it was characterised by a progressive worsening of the firms’ financial conditions.

The Impact of Criminal Infiltrations on Firm Performance

In order to estimate the impact of mafia infiltrations on firms’ performance, we set up an event study type of analysis with year- and firm-fixed effects, to account for common shocks and structural differences across firms. We also include controls for the economic cycle at the sector and province levels to account for possible shocks that may be common to narrowly defined clusters of firms.

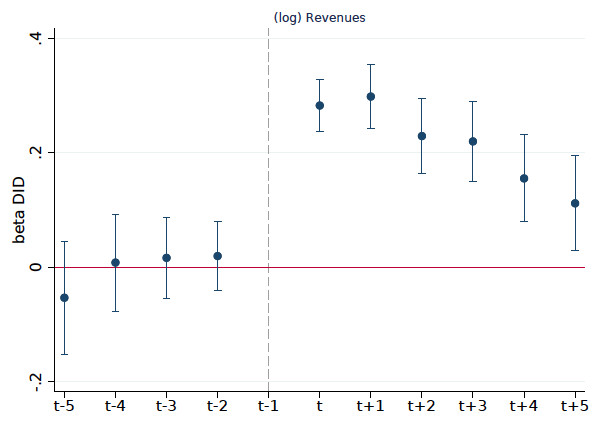

According to our most restrictive specification, ‘ndrangheta infiltrations increase the revenues of the treated firms by approximately 24%. Such increases are not permanent, but fade out gradually in the years after the infiltration (Figure 1). The positive impact of infiltration is the result of a marked increase in the revenues of the treated firms vis-à-vis the fairly stable patterns among control units.

Figure 1 The impact of ‘ndrangheta infiltration on firms’ revenue over time

Notes: Each point is the estimate of the treatment effect on the log of revenues for different years, before and after the infiltration (leads and lags); vertical bands are the corresponding 95% confidence intervals; t-1 is the reference category.

When considering the production inputs, we find that infiltrations generate an increase in the labour inputs but not in capital investments. This pattern is particularly enhanced among firms that operate in activities most closely related to the public sector, such as education and training, health, public utilities, and the whole construction business (mining and quarrying, construction itself, and real estate activities). Among the other activities, the increase in the production inputs is significantly less pronounced, suggesting that the higher revenues reported may be an accounting artefact to mask money laundering rather than real growth.

The Long-Run Effects of Mafia Spread

We then adopt a long-run perspective to shed light on the effect that such criminal infiltrations may generate broadly on the local economy. We build on the fact that, at the beginning of the 1970s, the ‘ndrangheta was essentially absent in the centre and north of Italy, while it progressively infiltrated these areas in the following decades. Its current extent in the centre and north of Italy can thus be interpreted as the result of the progressive penetration that occurred over the past 40 years.

Using our proxy for ‘ndrangheta infiltrations, we trace the patterns of penetration of the criminal organisation in the centre and north and match information at the municipal level with local economic activity indicators built from census data.

To account for the possible endogenous sorting of the ‘ndrangheta in certain areas, we rely on an instrumental variable approach that draws on hand-collected historical data about the forced relocation of ‘ndrangheta affiliates in ‘mafia-free’ areas from the 1970s on. Specifically, we instrument the presence of the ‘ndrangheta in a given municipality, as proxied by the share of local firms that we classify as infiltrated, with the (minimum) distance to a municipality where at least one ‘ndrangheta affiliate was forced to resettle.

We find a strong negative effect of the ‘ndrangheta on long-term employment growth: moving from a municipality at the bottom decile of the extent of ‘ndrangheta penetration to one at the top decile would lead to a decrease in employment growth of about 28% over a forty-year period. Such an effect is mostly driven by those sectors in which organised crime is likely to operate with the objective of making business, i.e. activities most closely related to the public sector.

Concluding Remarks

A deeper understanding of where and how organised crime operates in the legal economy is crucial in the view of containing its spread and ensuring smooth functioning of market competition and economic growth in the long run. In particular, effective monitoring of firms’ governance and of public-private sector relations can be especially helpful to fight the expansion of criminal organisations.

Authors’ note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Italy.

Notes and references available at original.

Maybe I’m misinformed but I’m pretty sure the banking industry accounts for way more than 2-5% of global GDP…

Agree – I’m sure this undercounts the money under the table, and does not see how the banking industry as a whole of Mafia-ized. Oh, well lies, damn lies, and…

Re undercounting, his methodology, with the weight given to last names and area of origin, seems very conservative. If anything, you’d think criminal organizations of that size and extent would learn to hide better.

This kind of economic analysis of persistent, accelerating predation is much needed.

The economic and political effects are Mobius-like in their slippery nexus; strangely conjoined.

They devolve exponentially, and trigger phase changes of economic and environmental dysfunction.

It’s sort of racist to limit “mafia” to Italians. Scratch Private Equity and you’ll start to find certain ethnic/national/religious affiliations more highly represented than in the general population — along with many of the “family” and “mafia” forms of corruption, intimidation, and predation.

Social Anthropologists will tell you that “mafias” arise in any society where the Rule of Law has broken down — as it has under Chicago School libertarianism/neoliberalism. Too Big to Jail has led to the rise of American mafias, the lawless Private Equity industry and the National Security metastasis of the Military-Industrial Complex foremost among them.

As malignant as the American FIRE sector is, it’s not a close analog to the Mafia…or the Camorra, or the ‘Ndrangheta. Closer analogs include the Yakuza, triads, Mexican cartels, Colombian cartels and the Russian mafia. These groups’ baseline income sources are illegal gambling, theft by violence, and illegal drug sales. Without this income, they’d be nothing. In the US, Italian/Jewish organized crime cartels were grafted on to the economy as a major economic force by Prohibition, which they violently exploited to earn vast sums of money. They continued on after Prohibition for several reasons: strong local Italian and Jewish communities where they were major forces, willful ignorance on the part of the FBI (read Hoover), and local and state corruption using their wealth. Their local ethnic support has vastly diminished as the population Americanized and dispersed from major cities. Then the FBI was forced to act after the publicity arising from the Apalachian meeting and Valachi hearings. Stronger laws and technological superiority enabled the FBI to penetrate and compromise the Cosa Nostra. Today, the organization is a shadow of itself forty years ago. There is no violence-based organized crime cartel/mafia that’s a major player in the US.

Re …”Of course, in this country we have private equity. So there’s that.”: seems to me the Soprano’s “bust-outs” analogy alluded to in this concise intro statement is not limited to leveraged buyouts and asset stripping by private equity firms and other shadow bank entities. There is also the issue of internal stock buybacks and massive cash dividend payouts by the CEOs and boards of large banks and corporations as Pam and Russ Martens discussed in their post this morning:

https://wallstreetonparade.com/2019/10/the-fed-fears-an-explosion-on-wall-street-heres-how-jpmorgan-lit-the-fuse/

In my view, this again points to the need to reinstate the Glass-Steagall Act to separate and shield the nation’s depository banks and payments system from this type of behavior and market speculations in highly leveraged financial derivatives.

I have been doing a lot of reading about the East India Company in it’s early days & Imagine that the likes of Luciano & Lanski would have likely behaved in the same way. The company got a big lift when a ship sent to the Indies to seek trade, decided instead to ransack a Portuguese Carrack of a million in loot. Clive the CEO was once a gangster who ran protection rackets & could be portrayedi in a Ye Olde Shrewsbury version of the Sopranos.

After looting the dying Moghul empire of which the largest collection of treasure in the World is still stashed away at the family seat under the control of Clive’s descendants. They went on to asset strip over a 5 year period, contributing to the causes of a famine that killed millions, hung thousands for not paying their taxes & eventually went broke requiring a TBTF bailout.

They were above the law & even when TSHTF only Warren Hastings was called to account & he was relatively innocent & largely got off with it. Personally I don’t see much difference in moral vacuity between the Mafia, EIC & those who run corporations today & I know that Clive would have fully understood someone like Michael Corleone wanting to go legit.

Using our proxy for ‘ndrangheta infiltrations, we trace the patterns of penetration of the criminal organisation in the centre and north and match information at the municipal level with local economic activity indicators built from census data.

Italy is among the European countries with a larger middle class than US, UK, and Canada according to a study done a few years ago.

https://www.aier.org/research/measuring-the-middle-class/

Measuring the Middle Class

And an American urban planner who now is spearheading movement for change in US urbanization because it is financially unsustainable, got his wakeup call in Italy:

https://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2019/10/21/why-decline-is-not-normal-2019

Why Decline Is Not Normal

Financialized housing has led to oligopolies in US, Canada and UK. Canada has an oligopoly that is strangling Maritime Provinces’ economies.

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/how-the-maritimes-became-canadas-incredible-shrinking-region/article23554298/

How the Maritimes became Canada’s incredible shrinking region

https://www.canadalandshow.com/podcast/family-owns-new-brunswick/

The Family that Owns New Brunswick

https://mondediplo.com/2019/04/13canada

Family that own a province

When there’s market concentration and the costs of entry are high—as they are in every industry in Canada that’s dominated by an oligopoly—incumbents don’t have to worry that an upstart might pop up out of nowhere and try to take them down.

https://thewalrus.ca/why-canadian-businesses-need-to-think-big/