This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 707 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser and what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current goal, funding comments section support.

Yves here. I hate to provide a long warm-up to this instructive articles about Gandhi’s views about corporation and commerce, but the post below treats the Business Roundtable’s recent lip service to the notion that corporations should serve broader corporate interests as genuine. Until Business Roundtable members put their money where their mouths are by changing CEO compensation metrics, and in particular making it less dependent on stock option goodies, this looks like an empty gesture to ESG (“environmental, social, and governance”) advocates.

However, it is important to understand how the toxic “shareholders come first” came to be widely accepted in American boardrooms. Hence this extract from a 2014 post:

One of my pet peeves is the degree to which the notion that corporations exist only to serve the interests of shareholders is accepted as dogma and recited uncritically by the business press. I’m old enough to remember when that was idea would have been considered extreme and reckless. Corporations are a legal structure and are subject to a number of government and contractual obligations and financial claims. Equity holders are the lowest level of financial claim. It’s one thing to make sure they are not cheated, misled, or abused, but quite another to take the position that the last should be first.

If you review any of the numerous guides prepared for directors of corporations prepared by law firms and other experts, you won’t find a stipulation for them to maximize shareholder value on the list of things they are supposed to do. It’s not a legal requirement. And there is a good reason for that.

Directors and officers, broadly speaking, have a duty of care and duty of loyalty to the corporation. From that flow more specific obligations under Federal and state law. But notice: those responsibilities are to the corporation, not to shareholders in particular…Shareholders are at the very back of the line. They get their piece only after everyone else is satisfied. If you read between the lines of the duties of directors and officers, the implicit “don’t go bankrupt” duty clearly trumps concerns about shareholders…

So how did this “the last shall come first” thinking become established? You can blame it all on economists, specifically Harvard Business School’s Michael Jensen. In other words, this idea did not come out of legal analysis, changes in regulation, or court decisions. It was simply an academic theory that went mainstream. And to add insult to injury, the version of the Jensen formula that became popular was its worst possible embodiment.

One good source for the fact that economists, rather than legal decisions, were the basis for the acceptance of this idea, is a 2005 article by Frank Dobbin and Dirk Zorn, “Corporate Malfeasance and the Myth of Shareholder Value.” This paper looked back to the 1970s, the era of diversified and often underperforming firms (remember the conglomerate discount?). Deregulation, high inflation, and a lax attitude towards anti-trust enforcment stoked a hostile takeover boom. Economists celebrated this development as disciplining chief executives and moving assets into the hands of managers who could operate them more productively. In reality, the success of these early deals depended mainly on asset sales, both of non-core operations and of hidden sources of value, like corporate real estate, as well as leverage and slashing bloated head office staffs (the across-the-company headcount efforts became more prominent in the 1990s).

But I’m now reading an advance copy of terrific book, Private Equity at Work by Elaine Appelbaum and Rosemary Batt, which adds important detail to the Dobbin and Zorn’s account. It’s done a remarkably impressive job of marshaling data about the private equity industry and explaining how it operates, which means debunking its claims about how it adds value. And even its asides are rigorous. For instance, its four page treatment on the origins of the “maximize shareholder value” line of thought showed real mastery of the source material.

Appelbaum and Batt trace the origins of the managerial model of capitalist enterprise to the New Deal securities laws. They helped institutionalize dispersed shareholding, and with it, a separation of ownership and management. From the 1930s onward, there was an active debate between two schools of thought. Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means were concerned that this new approach neglected shareholder interests. By contrast, Harvard law professor Merrick Dodd contended that large-scale corporations had broader social aims, including providing employment and useful goods. By the early 1950s, the Dodd view had clearly prevailed.

Although the writers of that era would never have used this framing, large corporations created reasonably efficient internal markets. Both employers and their workers benefitted from investing in a workforce that was also their main source for supervisors and managers of all levels. Indeed, middle and senior level executives hired in from the outside often found it hard to adapt to these well-established, tightly knit corporate cultures (note that well-established does not necessarily mean “well functioning”). The tendency of companies to promote from within versus the generally lower odds of succeeding in another company meant that most employees’ best prospects were within their current company, which gave them strong incentives to make it successful.

This was also the era when unions had clout. That assured that productivity gains were shared among workers, management, and investors. The fact that labor participated in these improvements helped propel a robust consumer economy, fueling more business growth. These enterprises typically took a long-term view, and used retained earnings to fund investments and research.

This model prevailed until the 1970s. Even though corporate profits as a percent of GDP grew in the 1970s even under stagflation (after the oil shock recession of 1974-5 had passed), return on capital had plunged from 12% in 1965 to 6% in 1979. Appelbaum and Batt describe the rise of the diversified corporation as one of the biggest culprits. They’d become popular in the 1960s as a borderline stock market scam. Companies like Teledyne and ITT, that looked like high-fliers and commanded lofty PE multiples, would buy sleepy unrelated businesses with their highly-valued stock. Bizarrely, the stock market would valve the earnings of the companies they acquired at the same elevated PE multiples. You can see how easy it would be to build an empire that way.

But these sprawling conglomerates had lots of managerial downside. Top brass often didn’t understand the operations of these new businesses. They became more dependent on finance staff to impose metrics across businesses to have a handle on what was going on. The formerly virtuous internal labor markets became balkanized and less salutary. And at a higher level, the various businesses were more likely to operate like fiefdoms competing for corporate resources. Finally, because the top executives treated these units as portfolio holdings that could be sold at any time, they were less certain of the necessity and value of investing in them.

By Geoffrey Jones, Isidor Straus Professor of Business History, Harvard Business School and Sudev Sheth, Senior Lecturer, The Lauder Institute, University of Pennsylvania. Originally published at The Conversation

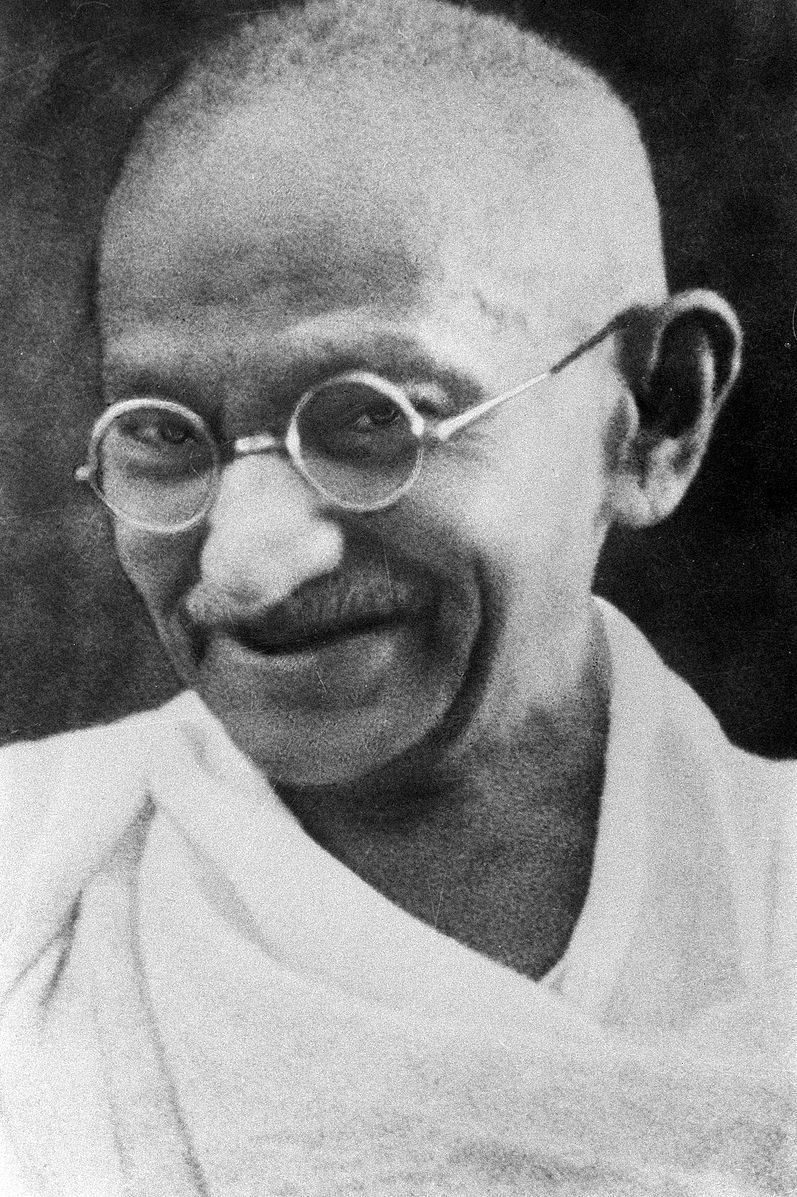

Mahatma Gandhi is celebrated across the globe as an idealist who used civil disobedience to frustrate and overthrow British colonialists in India.

The popularity of his nonviolent teachings – which inspired civil rights activists such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela – has obscured another important facet of his teachings: the proper role of business in society.

Gandhi argued that companies should act as trusteeships, valuing social responsibility alongside profits, a view recently echoed by the Business Roundtable.

His views on the purpose of a company have inspired generations of Indian CEOs to build more sustainable businesses. As scholars of global business history, we believe his message should also resonate with corporate executives and entrepreneurs around the world.

Shaped by Globalization

Born in British-ruled India on Oct. 2, 1869, Mohandas K. Gandhi was the product of an increasingly global age.

Our research into Gandhi’s early life and writings suggests his views were radically shaped by the unprecedented opportunities that steamships, railroads and the telegraph provided. The growing ease of travel, the circulation of print media and the increase in trade routes – the hallmark of the first wave of globalization from 1840 to 1929 – impressed upon Gandhi the myriad of challenges facing society.

These included vast inequality between the rich West and other parts of the world, growing disparities within societies, racial tension and the crippling effects of colonialism and imperialism. It was a world of winners and losers, and Gandhi, although born into an affluent family, dedicated his life to standing up for those without status.

The Horrors of Industrialization

Gandhi studied law in London, where he encountered the works of radical European and American philosophers such as Leo Tolstoy, Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson and John Ruskin – transcendentalists who advocated intuition over logic.Ruskin’s moving discussion of the ecological horrors of industrialization, in particular, caught Gandhi’s attention and led him to translate Ruskin’s book “Unto This Last” into his native Gujarati.

In 1893, Gandhi took up his first job as a barrister in the British colony of South Africa. It was here, not in India, where Gandhi forged his radical political and ethical ideas about business.

His first public speech ever was to a group of ethnic Indian businesspeople in Pretoria. As Gandhi recalls in his candid autobiography “The Story of My Experiments with Truth”:

“I went fairly prepared with my subject, which was about observing truthfulness in business. I had always heard the merchants say that truth was not possible in business. I did not think so then, nor do I now.”

Gandhi returned to British-occupied India in 1915 and continued to develop his ideas on the role of business in society by talking to prominent business leaders such as Sir Ratanji Tata, G.D. Birla and Jamnalal Bajaj.

Today, the children and grandchildren of these early Gandhi disciples continue to lead their family businesses as some of not only India’s but the world’s most recognized conglomerates.

The Role of Business

Gandhi’s views of what trusteeship really means were expressed in great detail in his widely popular Harijan, a weekly periodical that highlighted social and economic problems across India.

Our study of Harijan’s archive from 1933 to 1955 helped us identify four key components of what trusteeship meant for Gandhi:

- a long-term vision beyond one generation is necessary to build truly sustainable enterprises

- companies must build reputations that foster trust across transactions and with all sections of society

- business enterprise must focus on creating value for communities

- while Gandhi saw the value of private enterprise, he believed the wealth a company creates belongs to society, not just the owner.

Gandhi was murdered in 1948, just after India secured independence. However, his ideas have continued to resonate deeply with some of India’s leading companies.

Interviews conducted for Harvard Business School’s oral history archiveturned up surprising evidence in recent decades of Gandhi’s role in guiding modern companies in a variety of countries toward more sustainable business practices.

“We have to take care of all stakeholders,” says billionaire Rahul Bajaj, chairman of one of India’s oldest and largest conglomerates, recalling his grandfather’s association with Gandhi. “You can’t produce a bad-quality and high-cost product and then say, I go to the temple and pray, or that I do charity; that’s no good and that won’t last, because that won’t be a sustainable company.”

Anil Jain, vice chairman and CEO of the second largest micro-irrigation company in the world, recalls:

“My father was greatly influenced by Mahatma Gandhi who believed in simplicity – he believed that the real India lives in villages, and unless villages are transformed to become much better than how they are, India cannot really move forward as a country.”

What Would Gandhi Say

Gandhi’s views were constantly evolving in dialogue with the business community, and this is one reason why they remain so relevant today.

Imagine a Gandhian perspective on today’s tech companies. He would perhaps ask proponents of self-driving cars to consider the impact on the lives of hundreds of thousands of cab drivers around the world. He would ask proponents of e-commerce to consider the impact on local communities and climate change. And he would ask shareholders whether closing factories to maximize their dividends was worth making communities unsustainable.

Gandhi didn’t have had all the answers, but in our opinion he was always asking the right questions. For today’s business leaders and budding entrepreneurs, his wise words on trusteeship are a good place to start.

This article needs to include the *original* purpose of incorporation, which I believe-at least in the late 19th century US – was pretty limited to a single task-at-hand.

Here’s an overview of the origins of corporations, emphasizing that the earliest corporations were government subdivisions (i.e. the Corporation of London) and that most corporate charters were only granted for 20 years or so. The fiction of perpetual corporate life leads to a lot of these antisocial issues.

I’ve been thinking now for a while that we expect corporations to have split personalities. We give them an impossible task. We expect them to be socially responsible but we turn them into cutthroat competitors and cheaters. Instead of pushing our (now fading) delusion that “survival of the fittest” means survival of the most ruthless in pursuit of profits and growth, we need to get real as a capitalist country. Capital and capitalism have lost any significant meaning today. We aren’t building wealth and well being, we are building poverty and misery. We see big enterprises failing and we give them a tax break; we see our towns getting poorer and we induce Bezos to come in for a huge subsidy that will never pay off except as kick backs to politicians; we loan money hand over fist to a failing business paradigm; etc. We actually let the Fed buy up stocks to keep prices high. What we should do is discipline competition. Put a cap on profits. Stop subsidizing profiteers. Have a set of expectations that are doable and expect corporations to meet them. Actually prosecute fraud instead of calling it “immorality”. Legislate a few things. Maybe a standard for incorporation requiring them to improve society. The honor system is too conflicted to work.

The honor system is fine, but it doesn’t work on those who have no honor. About capping profits, etc. I think the way to go is “wage and price controls” which IIRC Nixon was the last one to entertain that idea. Agree wholeheartedly about prosecuting fraud. It would be a death blow to the US economy. Let all the stoners out of jail and fill the prisons back up with fraudsters.

Honor system never going to work, and the lack of “honor,” whatever that means, is just one reason. And remember that corporations now operate our branches of “government” as wholly owned subsidiaries that accept “legislation” wholly drafted to suit corporation purposes and neoliberal mandates. Said legislatures then apply the lipstick of “democratic legitimacy” and turn loose the forces of the state to shackle the rest of us to the corporate wheel.

And we mopes mostly still buy into the notion that electoral Kay Gabe will somehow result in fewer whipping and hangings, or at least better bunting and garland on the publi stocks and scaffolds.

Here’s another telling piece on how limited in scope and duration the corporation form was for many decades: “Our hidden history of corporations in the United States,” http://reclaimdemocracy.org/corporate-accountability-history-corporations-us/

what got me, when learning about the history of the corporation, was how everybody on the planet somehow forgot that these creatures are man made…that they exist at the pleasure of government…wouldn’t exist at all without the fancy paper stamped with a government seal.

and…more importantly…that when they screw up and run amok, that fancy paper can be burned, and they cease to exist. mr amazon, mr ibm, mr exxon, are merely sheafs of pretty paper in a vault somewhere…given form by sufficient belief that this makes them real.

death penalty for corporations is revocation of their charter.

instead, we treat them like a thunderstorm or earthquake…an act of nature(or nature’s god) that cannot be undone.

granted, like someone above alluded to, if we collectively found the stones to even threaten to tear up the charter for egregious violations of the social contract, our house of cards economy would likely collapse…still…given the alternative(becoming clearer by the day in the trendlines, to me at least), maybe a reset to zero is exactly what’s needed.

of course, now these things are supranational, having escaped the westphalian fences and become hypercosmopolitan first citizens of the earth…so without some supranational governing body(one that answers to actual humans, not wto, etc—which i see as a preemptive move by corpseworld to head off just such a global governance) I’m not sure what could be done to rein them in, let alone kill them off when they go too far.

I think it’s going to collapse either way, the question is simply whether the participants will ever have to take responsibility for it. The reason I think this is because fraud is just not a sustainable business model — it does nothing to create real wealth.

Ad on your site below the headline:

“By Agora – New Market Health

Atheists Left Shocked

New Evidence from the Great Flood is Proving Atheists Wrong. Click here to find out more…Read More”

You’re better than this. I come to this site to NOT have my intelligence insulted.

It’s too bad the site software does not impose a different color, type face and formatting for the advertisements like the one you confuse understandably as content authored by site participants. I don’t think NC, which like other still free sites depends in part on advertising and click revenue to keep operating, gets to choose the ad content that gets injected. My guess is that most participants recognize and push off the ads, though there have been some wildly humorous juxtapositions of ad copy and serious content…

Easy there, sport….

It’s just an ad. Helps pay for the stuff you DO come here for.

Imagine how different our world would be if the boards and senior managers of major corporations and banks had adopted this view as policy rather than the shareholder/CEO primacy of our recent past and current reality. Would globalization and labor arbitrage have happened? Would the financial crisis have happened? Would the effects of global warming and climate change be preoccupying thoughtful policy makers? Would we be concerned about such issues as invasions of our right to privacy or curtailment of our civil liberties as an outgrowth of domestic surveillance and information gathering by big companies? Would the looting of corporations through LBOs, corporate stock buybacks, huge cash dividend payouts and curtailment of R&D expenditures, product safety concerns, and many employee layoffs have occurred?… the high cost of prescription drugs or 737Max safety issues?… I think not. And perhaps we would also not be experiencing and addressing the debilitating social, economic and political effects that have resulted from the remarkable concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a relative few.

Unrelated, but needed “The Gandhi Affair” episode from the Seinfeld comedy series. Brief clip: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7–ZDROlhjE

The Gandhi content from the Business Roundtable was really quite lite. I’d be interested in understanding the context of his comments to possibly glean deeper insights. Based on my reading of the Experiments with Truth, I was so impressed by Gandhi’s work ethic and sense of honesty and perhaps these would also be his greatest contribution to a managerial philosophy. He believed that education was synonymous with moral development – not content assimilation – and believed such development came from hard work. On his Tolstoy Farm – which lived out another ideal he held of self-sufficiency – all the kids were expected to work very hard and meet exacting moral standards.