By Ashish Sinha, Professor of Earth and Climate Sciences, California State University, Dominguez Hills and Gayatri Kathayat, Associate Professor of Global Environmental Change, Xi’an Jiaotong University. Originally published at The Conversation

Ancient Mesopotamia, the fabled land between the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers, was the command and control center of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. This ancient superpower was the largest empire of its time, lasting from 912 BC to 609 BC in what is now modern Iraq and Syria. At its height, the Assyrian state stretched from the Mediterranean and Egypt in the west to the Persian Gulf and western Iran in the east.

Then, in an astonishing reversal of fortune, the Neo-Assyrian Empire plummeted from its zenith (circa 650 BC) to complete political collapse within the span of just a few decades. What happened?

Numerous theories attempt to explain the Assyrian collapse. Most researchers attribute it to imperial overexpansion, civil wars, political unrest and Assyrian military defeat by a coalition of Babylonian and Median forces in 612 BC. But exactly how these two small armies were able to annihilate what was then the most powerful military force in the world has mystified historians and archaeologists for more than a hundred years.

Our new research published in the journal Science Advances sheds light on these mysteries. We show that climate change was the proverbial double-edged sword that first contributed to the meteoric rise of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and then to its precipitous collapse.

Booming Right Up to an Unexpected Bust

The Neo-Assyrian state was an economic powerhouse. Its formidable war machine boasted a large standing army with cavalry, chariots and iron weaponry. For over two centuries, the mighty Assyrians waged relentless military campaigns with ruthless efficiency. They conquered, plundered and subjugated major regional powers across the Near and Middle East, as each Assyrian king tried to outshine his predecessor.

Ashurbanipal, the last great king of Assyria, ruled this vast empire from the ancient city of Nineveh, the ruins of which lie across the Tigris River from modern Mosul, Iraq. Nineveh was a sprawling metropolis of unprecedented size and grandeur filled with temples and palace complexes, with exotic gardens that were watered by an extensive system of canals and aqueducts.

And then it all ended within just a few years. Why?

Our research group wanted to investigate climate conditions over the few centuries when the Neo-Assyrian Empire took hold and then eventually collapsed.

Building a Picture of Climate 2,600 Years Ago

For clues about rainfall patterns over northern Mesopotamia, we turned to Kuna Ba cave, located near Nineveh.

Our colleagues collected samples from the cave’s stalagmites. These are the cone-like structures that point upward from the cave floor. They grow slowly, from the ground up, as rainwater drips down from the cave ceiling, depositing dissolved minerals.

The rainwater naturally contains heavy and light isotopes of oxygen – that is, atoms of oxygen that have different numbers of neutrons. Subtle variations in the oxygen isotope ratios can be sensitive indicators of climatic conditions at the time the rainwater originally fell. As stalagmites grow, they lock into their structure the oxygen isotope ratios of the percolating rainwater that seeps into the cave.

We painstakingly pieced together the climatic history of northern Mesopotamia by carefully drilling into stalagmites, across their growth rings, which are similar to those of trees. In each sample, we measured the oxygen isotope ratios to build a timeline of how conditions changed. That told us the order of events but didn’t tell us the amount of time that elapsed between them.

Luckily, the stalagmites also trap uranium, an element that’s ever-present in trace amounts in the infiltrating water. Over time, uranium decays into thorium at a predictable pace. So the dating experts on our research team made scores of high-precision uranium-thorium measurements on stalagmite growth layers.

Together these two kinds of measurements let us anchor our climate record to precise calendar years.

Unusual Wet Period, Then Massive Drought

Now a direct comparison of the stalagmite climate record with the historical and archaeological records from the region was possible. We wanted to place the key events of Neo-Assyrian history into the long-term context of our climate reconstruction.

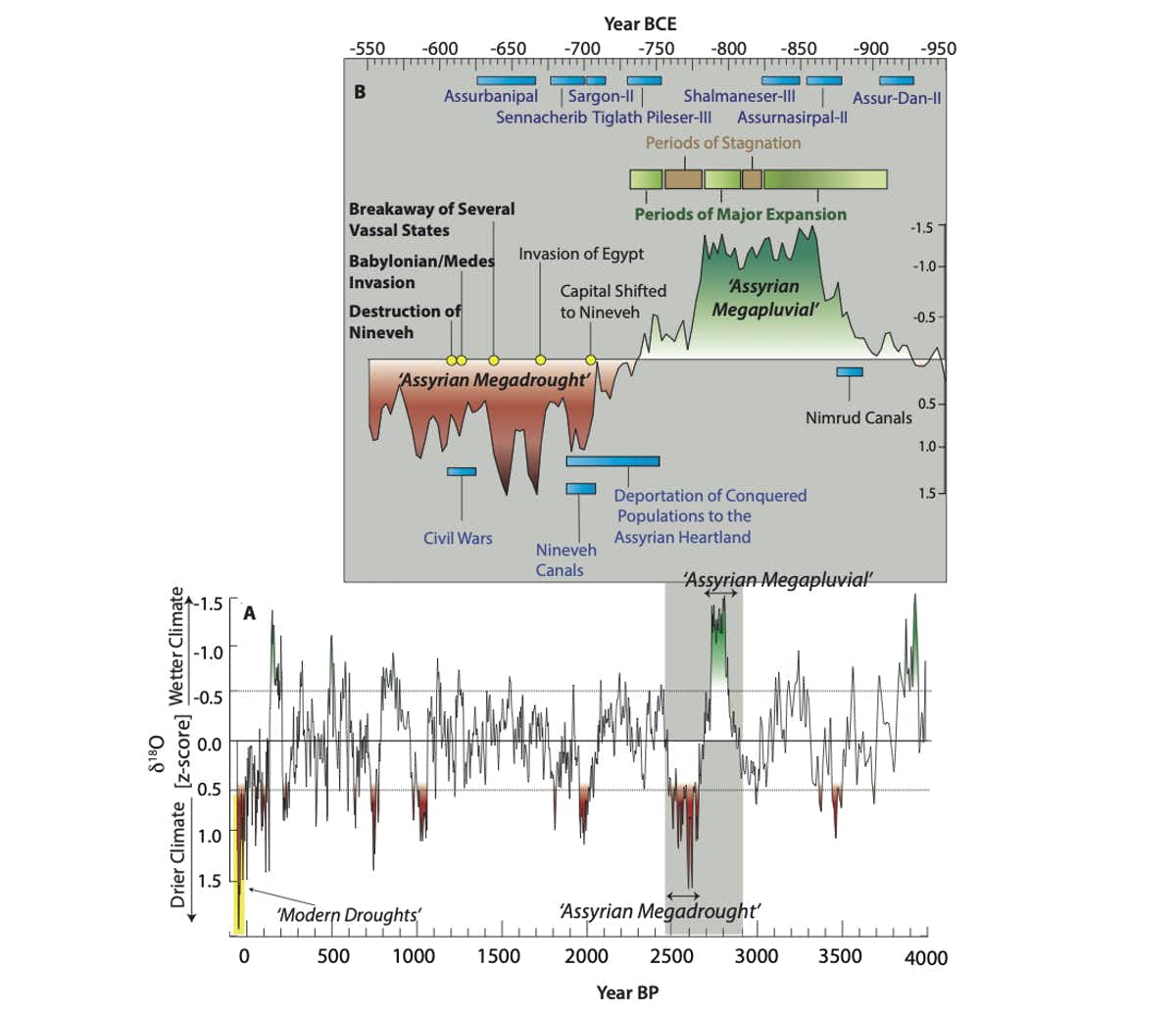

We found that the most significant expansion phase of the Neo-Assyrian state occurred during a two-centuries-long interval of anomalously wet climate, as compared with the previous 4,000 years. Called a megapluvial period, this time of unusually high rainfall was immediately followed by megadroughts during the early-to-mid-seventh century BC. These ancient dry conditions were as severe as recent droughts in Iraq and Syria but lasted for decades. The period marking the collapse of the Neo-Assyrian Empire occurred well within this time frame.

Mindful of the caveat that correlation doesn’t imply causation, we were interested in how this wild climate swing – an unusually rainy period that ended in drought – could have influenced an empire.

While the Neo-Assyrian state was huge in its final few decades, its economic core was always confined to a rather small region. This relatively small area in northern Mesopotamia served as a primary source of agricultural revenues and powered Assyrian military campaigns.

We argue that nearly two centuries of unusually wet conditions in this otherwise semi-arid region allowed for agriculture to flourish and energized the Assyrian economy. The climate acted as a catalyst for the creation of a dense network of urban and rural settlements in the unsettled zones that previously hadn’t been able to support farming.

Our data show the wet period abruptly ended and the pendulum swung the other way. In the grips of recurring megadroughts, the Assyrian core and its hinterlands would have been engulfed within a “zone of uncertainty” – a corridor of land where the rainfall is highly erratic and any rain-fed agriculture comes with a large risk of crop failure.

Repeated crop failures likely exacerbated the political unrest in Assyria, crippled its economy and empowered the adjacent rival states.

Uncertain Climate, Unsustainable Growth

Our findings have current-day implications.

In modern times, the same region that once constituted the Assyrian core has been repeatedly struck by multiyear droughts. The catastrophic drought of 2007–2008 in northern Iraq and Syria, the most severe in the past 50 years, led to cereal crop failures across the region.

Droughts like this one offer a glimpse of what Assyrians endured during the mid-seventh century BC. And the collapse of the Neo-Assyrian Empire offers a warning to today’s societies.

Climate change is here to stay. In the 21st century, people have what Neo-Assyrians did not: the benefit of hindsight and plenty of observational data. Unsustainable growth in politically volatile and water-stressed regions is a time-tested recipe for disaster.

I can’t help but think of California after reading this. After piecing together the cluster*bleep* of increasingly ferocious wildfires, years long droughts (that’ll likely become decades long soon enough), the housing crises, the general unwillingness of California politicians to impose any kind of water restrictions on the corporate farms and whole swaths of the state slowly becoming uninhabitable, it’s easy to see California collapsing. I recently considered the possibility that, while I grew up here, I may not grow old here.

The sad thing is…we’re still at a point where these problems can be solved. It won’t be easy, but it is doable. The problem is the political class are more interested in pandering to wealthy boomers clinging to a bygone era at the expense of the livability of younger generations. I don’t see that changing anytime soon and by the time we have a political class willing to do something meaningful, it’ll likely be too late.

“The problem is the political class are more interested in pandering to wealthy boomers clinging to a bygone era at the expense of the livability of younger generations.”

What are you specific suggestions to solve these problems?

Very good find – excellent research both by the authors and NC.

Unsustainable growth in politically volatile and water-stressed regions is a time-tested recipe for disaster.

I’d restate this a little:

Unsustainable growth in politically volatile and water-stressed regions is a time-tested recipe for disaster, and similar growth could also trigger political volatility in stable regions.

See Empire of Chaos.

Chaco Canyon is a regional example of similar stress here in New Mexico. An excellent account is David E. Stuart’s “Anasazi America” which has the subtitle “Seventeen Centuries on the Road from Center Place”.

I quote from the back cover blurb:

“At the height of their power in the late eleventh century, the Chaco Anasazi dominated a territory in the American Southwest larger than any European principality of the time. Chacoan society thrived for over two hundred years, then collapsed dramatically in a mere forty years. Why did such a great society collapse?…”

I second that book recommendation, and urge you all to visit Chaco Canyon, which is the finest ruins in these United States as far as i’m concerned.

“Chacoan society thrived for over two hundred years, then collapsed dramatically in a mere forty years.”

Remarkable coincidence in the timelines. Weather is always a big factor in farming and for any society dependent on it, but I wonder if there’s a human dynamic involved, too. That is, that’s about how long ANY empire will last. How does it compare with the height of the Roman empire? Or Britain’s? I was struck by “They conquered, plundered and subjugated major regional powers across the Near and Middle East, as each Assyrian king tried to outshine his predecessor.” IOW, they were building up ill will among all the neighbors. How long before that catches up with them, as it evidently did?

Probably until they show weakness – like a major drought, or a dynastic squabble (“civil war”).

The truth is that political regimes, especially imperial ones, have lifespans. They burgeon and decay, and to some extent that process is built in. The PEOPLE live on, most of them; there are still Romans in Italy and English in Britain, but they no longer have empires and their political system has changed radically since then. Incidentally, there are still Medes, too; last I heard, they’re now called the Kurds (correct me if I’m wrong – old information).

The Chacoan culture was post-peak when a punishing drought came calling…

Very similar to what will be hitting us, and it used to be that we were Johnny on the spot when it came to natural disasters in our response, now we’re unable to put things right again. a harbinger likely to only get worse.

And soil erosion.

Conquest of the Land Through 7,000 Years

“Lowdermilk studied the record of agriculture in countries where the land had been under cultivation for hundreds, even thousands, of years. His immediate mission was to find out if the experience of these older civilizations could help in solving the serious soil erosion and land use problems in the United States, then struggling with repair of the Dust Bowl and gullied South.”

“He discovered that soil erosion, deforestation, overgrazing, neglect, and conflicts between cultivators and herders have helped topple empires and wipe out entire civilizations. At the same time, he learned that careful stewardship of the earth’s resources, through terracing, crop rotation, and other soil conservation measures, has enabled other societies to flourish for centuries.”

Download and read free here. Your tax dollars at work for something productive:

https://archive.org/details/CAT31293292

nature stresses states and other states stress states. the US is stressing how many other states around the world? No particular point implied just a question. The Soviet Union’s collapse, I assume, is explicable in other ways and no criticismm implied of the methodology. Existence is stress in one sense would be the platitude.

Though this is very interesting–and drought no doubt played an enormous role in the weakening of the Assyrian Empire–I think the article under-appreciates how easily large creaky empires can crack when challenged by smaller, nimbler polities.

For an example, see the glorious Persian empire, truly the Mediterranean super power of its day, and the spunky Greek city states, fractious yet with a decentralized system that allowed for social creativity. It did not take long for the Persian Empire, its arrogant bubble burst after its first defeats by the Greeks, to totter and fall, no drought needed.

From my historical studies, I’ve come away with an interesting observation: people tend to idolize large, centralized systems as the epitome of human achievement in the political and social realms. However, history shows us time and again that such systems, though seemingly indestructible once established, soon fall suddenly away like so much dust, shocking not only their enemies but also the very populations that live under their yoke! For a recent example see the collapse of the Soviet Union. Generally, people–even the most learned among us–overestimate the resilience of these political formations, which, at their most centralized (and glorious) are often in their decrepitude!

“I think the article under-appreciates how easily large creaky empires can crack when challenged by smaller, nimbler polities”

Something similar occurred to me, as well.

Large pre-industrial empires have major problems that are very difficult to solve, and may be forced into short term strategies that eventually lead to other very difficult problems.

The Roman empire, for example, was of a size that made peripheral difficulties very hard to manage. Roman legions, given good roads, could move at a sustained rate that can be expected to destroy cavalry based armies. Before mechanization, the only faster way to move forces would be good ships, but even given the rapid pace of their infantry, the empire was about 122 days across.

Given movement times and communications delays, provincial forces could not expect help from other parts of the empire in the same campaigning season. They were on their own, and would succeed or fail purely on the strength of their local assets. In order to defend the provinces, forces must be spread among them, so that only a small fraction of the imperial strength was available to face any external threat.

Similarly, central reserve forces would be too far away to intervene promptly, and if committed, would get farther away from other potential conflicts. This can be mitigated by developing a protective assemblage of client states to contain anything other than major assaults, but over a century or three, the need to reign in those same states drives an expansion of the area of direct imperial control, thus increasing the perimeter that must be defended, and spreading available forces even farther. Eventually things tend to get out of control, largely aided by exceeding a reasonable size for timely communication and transportation.

If you are interested in such things you can find a discussion of these issues, as well interesting gems like an explanation for the height of Hadrian’s Wall in the excellent “Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire” by Edward Luttwak.

And I read an article about Rome that climate change killed it, because a drought was bad, and was driving ‘ barbarians to Rome. But they couldn’t support adding so many. It was an ancient empire, with more slaves than citizens. And they started using ‘ barbarians ‘ in their military.

The article appears to assume that the outside invaders to Assyria had territory that did not suffer a drought – or not so much? Was this true? If not, then the collapse may have been hastened by other causes, such as the ones you mention.

As I read this post I became aware of a peculiar impact such studies and findings could have. I believe there is a soothing element in these discoveries from the past. The change in rainfall this post documents does fit the definition of climate change and I do not doubt the impacts that would have on a civilization or geographic region. The climate change we face — I prefer to call it Climate Chaos — will be nothing like this regional variance in rainfall. The Climate Chaos we face promises to be several orders of magnitude worse than this climate change that helped bring down the Assyrian Empire. It is worthwhile to notice the impacts of shifting patterns of rainfall on agriculture and the impacts that can have on human societies. We already see shifting patterns of our rainfall. But it must be remembered the Climate Chaos we face has broader reach, brings far greater changes, and these ‘changes’ will move with unprecedented speed as they accelerate toward an unknown destination.

Thanks for this post. Archeology is brain candy as far as I’m concerned, and of course this item has contemporary relevance – although I’d 2nd Jeremy’s caveat: worldwide is likely to be a bit different, as in worse. And the globalizers have gone to great lengths to assure there are no refuges – we all go down together.

Hmmm – exception: climate chaos will choose winners and losers. Basically, everything moves away from the equator; hot dry places become uninhabitable, northern, wet places will be able to grow crops they can’t now. The big winners, once they get over the transition, will be Canada, Alaska, and Russia. Go North, young man, if you can.

A thousand years ago, European-born Greenlanders used to raise cattle. Then, they all died because a cold era began.

Should modern Greenlanders expect to grow wheat in the near future? That would be something.

Increased agricultural productivity during the megapluvial period could help explain how the Assyrians were able to conscript much of their adult male population into their army. By all accounts their military was unprecedentedly large, 200,000 total with a typical expeditionary force numbering 70,000. Armies this big could have overcome any opposition by sheer attrition.

Also interesting to note that the large-scale deportations of conquered peoples coincides with the start of the dry period. With Assyria now committed to holding down an enormous territorial superstate with its big army, some way had to be found to compensate for the falling agricultural productivity caused by the dry weather. The answer? Forced labor from the conquered regions.

Adding the usual caveats about correlation/causation, post hoc ergo propter hoc etc., etc.–an interesting line of speculation.

Makes sense. I have read credible sounding theories how in pre-modern times good productive conditions lead to population growth and this leads to oversupply of people as the amount of arable land doesn’t grow with population. Easiest way to put this oversupply to productive use is conquest as otherwise the fundamentally unneeded oversupply might cause internal tensions. Conquest then allows the elites to entertain their power fantasies and egos while the oversupply fighting in military goes through this evolutionary competition where victors (those who live through it) are rewarded with reproductive opportunities and those who die are naturally lost from the genepool. Yes, I’m being very male-centered, but that’s how pre-modern times operated. But while it was male-centered, being male in those times wasn’t always such a nice thing, many died fighting pointless wars. From this male-centered oversupply narrative, the expansionary military action is beneficial for that empire’s local and absolute elites. It reduces the male competition and also frustration from the inequalities that could cause internal tensions in the society because the inequalities of hierarchical agricultural societies can’t be realized when you are a cog in machine fighting glorious war away from home.

Luckily enough especially the western countries seem to limit our reproduction naturally, so the young men aren’t sent to fight foreign wars in the name of the ruling elites, right?

Sure enough these fairly primal motivations aren’t very popular in the modern days of enlightment, but have we really and absolutely grown to some more developed next level, or is the relatively long period of peace and plenty blinding from us from our underlying animalistic and primal motivations?

For those who like this sort of article Richard Bulliet ‘s “Cotton, Climate, and Camels in Early Islamic Iran: A Moment in World History” tells a very similar story of a regional climate shift that did in a thriving society. In this case it occurs a little bit to the west and later in time: Eleventh Century Persia.

It is an important event because it ushered in the Seljuk Turks into the area. And when the (now- Islamicized) Turks met the Christian Pilgrims in the Holy Lands, they didn’t get along so well.

The book has a similar investigative feel to it as this article does.

To add some balance to NC climate discussion: Legacy of Climategate 10 Years Later – by Judith Curry.

https://judithcurry.com/2019/11/12/legacy-of-climategate-10-years-later/#more-25412

Nice piece of deductive reasoning here in the techniques that they used. If this region went into a mega drought, it would have all sorts on consequences. If the Assyrians used cavalry and chariots to a large degree, then drought conditions would have meant that there would have been nothing for the horses to eat too far from home and they would have starved. Most armies lived off the land where ever they went but grains to seize must also have been in short supply.

Cannot say that I am sorry to see this empire becoming toast. The Assyrians had a reputation for being extremely ruthless and cruel and they must have been hated by their neighbours. When they went down, you can bet that there was a lot of pay back in mind at the end-

https://www.ancient.eu/Assyrian_Warfare/

I do not know how true it is but I have read that the colonization of the Australian colonies took place during a ‘wet’ period but as everybody knows, all good things come to an end.

I have believed now for soon a year that the climate example described here is the way todays Global Economy and many countries with it will collapse. Most of food production is still strictly annual, there aren’t some huge stockpiles to sustain for example the whole of Europe for multi-year megadrought. Sure if the megadrought becomes limited only to Europe then enough food supplies can be probably imported. But with the proven global warming there is very little reason to expect all the future droughts are local, the hot and dry Summer of 2018 was hot and dry also in many other places than just Europe.

When the food supply collapses without suitable replacements the states, economy, and the world as we know quickly collapses. Even personal preparation in form of own small scale subsistence farm is no guarantee of survival because the organized state can turn totalitarian command state in blink of an eye when the officials realize even they and the city populations (the elites tend to dwell in the cities themselves) are going to starve. I do not mean to antagonize anyone, I have the deepest sympathy for most people, but it’s pretty well established fact that human cooperation stops when peaceful cooperation means one party will die, i.e. we leave the world of plenty. Standing military personnel are really going to peaceful starve in their barracks when they have guns and firepower available. These are very real and humane reactions, which I understand, I’m just saying it’s not going to be nice ride and I think we are on the clock – this is the future waiting for us. I hope I’m wrong, but when and if the time comes none of us will be posting about it in the internet because there won’t be internet at that point.

Yes, I’m very cynical, but it’s really hard to be positive about this climate mess and the mind boggling amount of inaction and outright denial. Also the food supply considerations are rarely discussed, instead most of discussion is about melting glaciers and rising oceans which by my view are only an afterthought with the food security issues. The world is going to keep warming at current trajectory for many decades, and how this will affect agricultural questions is a massive question. By my understanding significant portion of our supercomputer capacity is used for near term weather modelling, which just goes to prove that decadal modelling is far more difficult because we struggle even with annual modelling. Most long term climate models extending to 2050-2100 are at best well informed guesses.

Ten years ago, I argued that Australia was going to have massive problems, because of water. It is the driest inhabited continent (Antarctica is the driest), but most of its exports are massive water-consumers. Basically, for all terms and purposes, it exports water, its scarcest commodity. How does that end well?

Aussie friends I have laughed at me at the time. They don’t anymore.

Totally agree here. The CSIRO came out with a report about a decade ago that said that each ton of wheat shipped overseas was mostly shipped water that was never coming back. And that the rain belts which fell on the mainland had shifted south and now fell into the oceans south of the continent. But our governments have allowed crazy stuff like growing rice and cotton in the middle of a desert using diverted river water which starves farms downstream of vital water. Gaaach!

It’s not just agri, the whole extraction industry uses a lot of water. Some is recovered, but a lot of it’s lost..

Get this. The mining industry is so hungry for water that a proposal was made to build a dam in Papua New Guinea, as in somebody else’s country, and then pipe it to the mines in northern Queensland. Unbelievable.

Yep. Been saying this for awhile…water wars are next…