Yves here. Even though this Chile case study describes how supposed “less lethal” weapons are used, too often deliberately, to inflict permanent damage, the potential for widespread misuse is obvious.

The weapon of choice for official abuse in the US appears to be the taser. Below is one of many examples of legal torture. Notice how the officer twists the passenger’s arm into a painful position, assuring he’ll try to pull away to prevent damage to his shoulder, then uses that as an excuse to taser him into submission, including tasering his genitals. This video is only for those with strong stomachs:

For a broader look, see this 2018 New Yorker story. Sadly, it is about the self-licking ice cream cone of the leading Taser firm Axon going gung ho into police body cameras. Key section:

Critics argue that, in the wrong hands, Tasers can be equally brutal. Civil-liberties and anti-torture groups have long complained that police officers, rather than resorting to Tasers strictly as an alternative to deadly force, often use them in situations that would never warrant firing a gun. Two years ago, after police in North Carolina Tased a mentally ill man five times in two minutes while trying to pry him off a stop sign—he was pronounced dead at the hospital—the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit ruled that using a Taser against someone resisting arrest was “unconstitutionally excessive.” A recent Reuters investigation found that, since 1983, a thousand and five people had died in the United States in incidents that involved Tasers, as part of a “larger mosaic of force.”

I also wish the article had described whether there were any good ways for protestors to protect themselves from eye mutilation by “less lethal” rubber bullets. But then again, in the US, meant to be helpful advice that doesn’t work too often can be the grist for litigation.

By Luciana Pol, an Argentine sociologist, and a Senior Fellow in Security Policy and Human Rights at the Center for Legal and Social Studies (CELS). Her main areas of work are drug policy and human rights, security policies and social protest. Originally published at openDemocracy

Sebastian Piñera’s government confused the human rights NGO with an armament manufacturer and requested a quote for 100,000 tear gas cartridges, 50,000 rubber bullets and 7,000 liters of pepper spray. Social protest had sparked a week before and the government was getting equipped to face it.

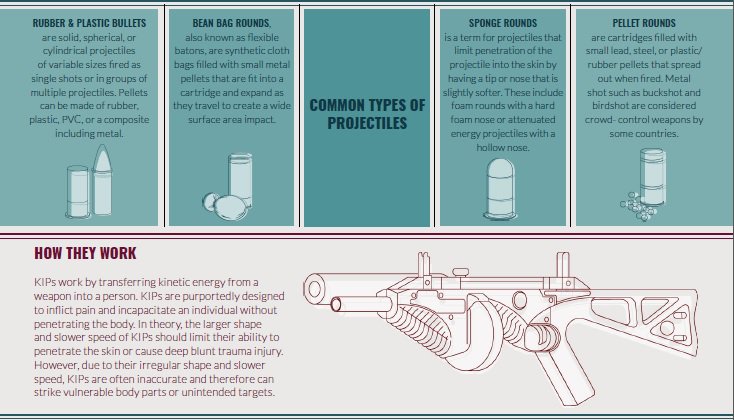

Police and military repression in the last 6 weeks in Chile has left a toll of arrests, injuries and deadly victims unseen since the days of Pinochet. These events have made clear that the use of less-lethal weapons (LLW) is unfit for crowd control. They are misused by the forces who manipulate these weapons without any supervision or evaluation. This situation renders it impossible to diminish, prevent and investigate abuse in the forces’ management of social protest.

It’s Not the 30 pesos, It’s the 30 Years

The last two months in Chile have been exceptional. An increase in the price of subway tickets in mid-October paved the way for a generalized cry of discontent that brought millions of people to the streets questioning the social and economic model of their country. “It’s not the 30 pesos, it’s the 30 years”, was the expression of exasperation that could be read on protest signs lifted from North to South of the Andean country, about the lack of social reform since the democratic transition of 1990.

Since the beginning of the unrest, the authorities’ reaction has been hard, repressive, sustainedly violent and indiscriminate. Multiple organizations of civil society and public institutions are monitoring human rights violations. Murder, torture, sexual abuse, arbitrary arrests, persecution of community leaders and illegal use of force are some of the situations reported by the international observers who traveled to Chile early November 2019. When the human rights organizations mission arrived in Santiago, the protests’ death toll had already reached 20 and hundreds had been injured. The mission’s conclusions and recommendations are eloquent.

Non-Lethal vs. Less-Lethal weapons

A notable trait that the mission observed in Chile is the widespread abusive, disproportionate and illegal use of rubber bullets and pellet rounds by Carabineros. The police have provoked until now over 200 eye injuries which have lead to total loss of vision in some cases. As the Chilean Red Cross reported to the Reuters news agency, more people have lost an eye in the first three weeks of protest than in the past 20 years.

The use of less-lethal weapons –which also namely include tear gas and water cannons– has been disputed for a few years in different parts of the world. Lebanon, Irak, Hong Kong, Ecuador, Colombia, and Chile are but a few examples of countries that have resorted to LLW in the past three months, resulting in injuries, permanent disabilities or even death of protesters and passersby.

On one hand, the reiteration of these events invalidates the original designation of “non-lethal” weapons, wrongly applied by media, police and military forces in Chile and elsewhere. Given their potential, it is fairer to qualify them as “less-lethal”. Most of these weapons were developed for military purposes and are today used for crowd control. A version of wooden bullets, for instance, was introduced by the British colonial forces and used against protesters in Malaysia, Singapore, and Hong Kong in the 1960s. They were later transformed into PVC bullets used in Northern Ireland.

On the other, these weapons are heavily questioned because there are no standards that control their production and trade nor their use in protests. International mechanisms haven’t been able to keep up with the rapidly evolving technology and strategies of crowd control. Governments have implemented their use with no appropriate regulation or training.

Is the Use of Less-lethal Weapons Necessary in Protests?

The answer varies depending on the type of weapon and its application.

Law enforcement authorities are bound by international standards to make rational and progressive use of force and in that sense, they require an option between batons and firearms. LLW in social protest may appear as an intermediate alternative, however, practice shows that their indiscriminate use provokes serious injuries.

The absence of regulation means that supply and demand dictate what gets produced and commercialized. The development of this type of weapons has expanded worldwide during the last two decades and the number of manufacturers has grown substantially. Before the absence of guidelines on the safe use of these weapons emitted by competent authorities, the current situation is that user manuals for these weapons are handed to the police by the manufacturers.

This sector has expanded substantially in the past decades without any type of public regulation, sometimes putting innovation to the service of increasing the harmful potential of LLW, enhancing their destructive potential or extending recovery periods at an unacceptable human cost. How hard or large should rubber bullets be? What are the correct concentrations of chemicals in tear gas cartridges? How hard should the water be spayed by the cannons? What is the right composition of pepper spray? All of these questions today share a common answer: whatever the manufacturers decide.

The Human Cost of Repression

Six weeks into the social protest in Chile, the price that people have had to pay because of the government’s reply is incalculable. The Chilean case dramatically showcases all of the problematic aspects of these weapons, particularly when it comes to pellet rounds and rubber bullets.

First, the weapons used are too dangerous and should in no case be used for crowd control. The composition of the ammunition used in the protests is under scrutiny ever since the Engineering School of the Universidad de Chile conducted analyses and found that Carabineros’ rubber bullets are composed of only 20% rubber, the rest being mainly lead and other hard substances. These results clash with the information provided by ammunition manufacturers.

Second, the use made of these weapons is inadequate. One of the most noticeable examples of this in the region including in Chile is the use of rubber bullets to disperse crowds in protests. This method, normalized within police institutions, carries enormous risks: shot at short range, rubber bullets can be as deadly as live ammunition. From afar, their trajectory is imprecise. Injuries on the back and buttocks reveal that individuals are fired at while trying to escape and the shots were executed to prevent their retreat.

Excessive force by police is not exceptional in Latin America. Carabineros, like many other institutions in the region, has a heavy military influence which reflects in some ongoing practices from the dictatorship era (1973-1990). It hasn’t undergone any substantial reform since the democratic transition.

And third, the Chilean case highlights the wrongful and abusive use of these weapons with the specific goal of causing harm. The 241 eye injuries are evidence of shots fired to the face, at short range, and on purpose, as reported in numerous testimonies. According to Dr. Rohini Haar, medical expert of Physicians For Human Rights and researcher at Berkeley University, California, “from a medical point of view, these weapons should not be used in protest. Dozens or sometimes hundreds of small pellets are shot simultaneously. When they impact sensitive areas such as the face and neck, they can cause death, blindness, brain contusions and other disabilities”. Since the beginning of the protests in Chile, more than 8000 detentions have been reported and 2800 people were wounded. Among these injuries, 1180 were caused by rubber bullets or pellet rounds.

Observers, Scientists, and the International Community

According to Andrés López Caballo, a lawyer at the Center of Legal and Social Studies (CELS) and member of the mission of International Human Rights Observers that visited Chile in early November, “the courts have failed to protect protesters and control state violence. They’ve merely adopted a reactive posture and have limited their actions to investigating already perpetrated abuse. There are no true elements of prevention or protection. In parallel, the government’s position is to defend the forces”.

Lack of monitoring and accountability is another troubling aspect of the use of less-lethal weapons in Chile. Since LLW are considered innocuous, there are generally no supervision mechanisms to control its use, creating yet another obstacle in controlling responsibility in the event of inadequate or excessive use.

Coincidentally, while protests were unfolding in the streets of Santiago and other Chilean cities, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights published the first international guidelines on the matter, the United Nations Human Rights Guidance on Less-Lethal Weapons in Law Enforcement. The UN advises to limit the use of less-lethal weapons to the last resort solution and to encourage in its place tactics of de-escalation of violence, avoiding panic and confusion.

Shots to the face and upper body constitute an illegal use of these weapons.

An encouraging sign in the current context has been the position of the medical community in Chile. The Medical College and the Ophthalmology Society have voiced their disapproval of the authorities’ use of less-lethal weapons. It’s time to consider the abundant empirical evidence to terminate the indiscriminate use of these weapons for crowd control.

****

CELS, a member of the INCLO network, has been working for years with other social organizations and experts on the use of less-lethal weapons in social protest. Based on our monitoring and research, we consider that rubber bullets and pellet rounds are not adequate for crowd control and therefore their use should be prohibited in protests.

Thinking about that video clip and how it relates to what is happening in Chile – or France for that matter – I began wondering if there was a correlation between the equipment that police use and how they handle a situation. That is, the more tactical gear that police have, the more they will be inclined to use it whether it is needed or not. That it encourages a different mind-set.

That video, by the way, should be played in Police Academies as a case study on how to escalate a situation without necessity which potentially lands your city in a civil lawsuit. The guy in this video was held for a few months and then all charges were dropped. Probably afraid to take the video to court. And an expert has said that the reason the cop used to pull the car over was made up as it was not possible for him to see what he claimed to see that led to pulling over that car.

So you can see they all had on the tactical gear and because the cop had a taser, it was his job to use it whether it was required or not. Borrowing a concept from the US military – that of ‘overmatch’ – they already had him outnumbered and had the drop on him but still it was escalated several levels in order to whack more charges on that guy. I sometimes wondered if the stupid haircuts that some of the police had helped shaped how they thought of themselves.

But to be fair, there are all sorts of cops. You have good one, bad ones and those just doing their job and I have a video illustrating this. There is a practice called ‘swatting’ where you call the police on a guy live-streaming him playing a game to see the police arrest him – a practice which has had fatal consequences. Here is a 10-minute clip of ten ‘gamers’ being swatted on live stream and note the different types of police responses. The police in one military-style raid were very disturbed to realize that they were being watched online and talked about (6:45 on) even though they had all the guns. And note these responses to what gear they are carrying-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gedVHbgIt7c

Re from article: “Shots to the face and upper body constitute an illegal use of these weapons.”

An 18-year old Colombian (Dilan Mauricio Cruz Medina) recently passed away as a result of an injury to his head caused by a projectile fired by an agent from this country’s special tactics police force, known by its initials as ESMAD. His act? Picking up and throwing a tear gas canister back from whence it came.

And on cue, government officials (e.g. president, ex-president, cabinet ministers) defended the police person who shot the bullet since, according to the defenders, use of these weapons is internationally sanctioned and permitted in cases of threats against public order.

From the link below (in Spanish):

Colombia’s Chief of Police, Óscar Atehortúa, indicated that the agent who shot the young person has been identified, the police agent, “has been separated from his functions…The police officer who fired the weapon acted legally…”

https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-50526848

Firing a teargas canister at the unarmed is peachy and lawful while throwing it back at the armed and armored security forces is what the Bad People do. Well, that makes it all okay to extrajudicially murder the Bad People.

Can I assume we all know that teargas canisters have injured, blinded, and even killed people albeit, I also assume, unintentionally?

Yellow Vest demonstrators against Macron in France have lost twenty-four eyes and five hands to “less lethal weapons.”

https://www.newstatesman.com/world/europe/2019/11/year-gilets-jaunes-have-lost-24-eyes-and-five-hands-and-made-deep-mark-french

It’s important to keep in mind that this is what a strong EU central government, commanded by Macron-type neoliberal technocrats and having its own military, would be like.

That doesn’t follow — the EU isn’t structured like France, which has a strong presidency. It could be worse, it could be better, it could be no different, it’s a difficult analysis because of all the dimensions. But France doesn’t model “the EU’ any more than the UK, Hungary or Malta.