Paul Volcker, the former Federal Reserve chairman often called “Tall Paul” for his 6’7″ stature, is dead at 92. Volcker played an outsized role in shifting the prevailing economic model from one dominated by labor to one dominated by capital. As Mark Blyth put it in a recent talk, the late 1970s and early 1980s, the rise of the “independent” central banker, which Volcker exemplified, was a core element in the economic regime change after the moneyed classes saw workers as being too empowered and revolted. His fixation with reducing inflation favored investors over workers, and lowered labor’s wage share of GDP. As as we’ll see, Volcker sought to achieve that end.

It took me quite some time to get a better perspective on Volcker. I was imprinted by the Wall Street of 1981, when Volcker was in the midst of implementing what he’d billed as a money supply experiment in order to wring inflation out of the system. The Fed money supply figures were announced every Thursday at 4:00 PM, after the market had closed (then at 3:00 PM). Even on the investment banking floors, someone would inevitably hover around the Quotron machine and would broadcast the latest money supply increases, and whatever the hot takes there were on what it meant.

At the peak of his money supply experiment, banks were hemorrhaging losses on their credit card portfolios, which yielded only 19% when it cost 22% to fund them. The economy went into a steep slide, the worst since the Great Depression. Securities firms like Goldman were also suffering. The institutional sales force, both equities and fixed income, was crying for lucrative new issues. But few companies who didn’t have to wanted to sell shares in the “death of equities” era, nor did they want to issue bonds at prevailing rates of 13% to 15%. Structures with tax advantages like zero coupon bonds and debt for equity swaps became popular.

Volcker relented in August 1982. I recall the word going through the firm like lightening that the Fed was going to ease up. There was no news announcement; primary deals apparently got the signal from the New York Fed’s trading desk. Later write-ups of this era suggested that Volcker wanted to persist even longer, but that the Latin American sovereign debt crisis, and the very real risk of US bank failures (recall that that serial near bankrupt Citibank was looking wobbly) stayed his hand.

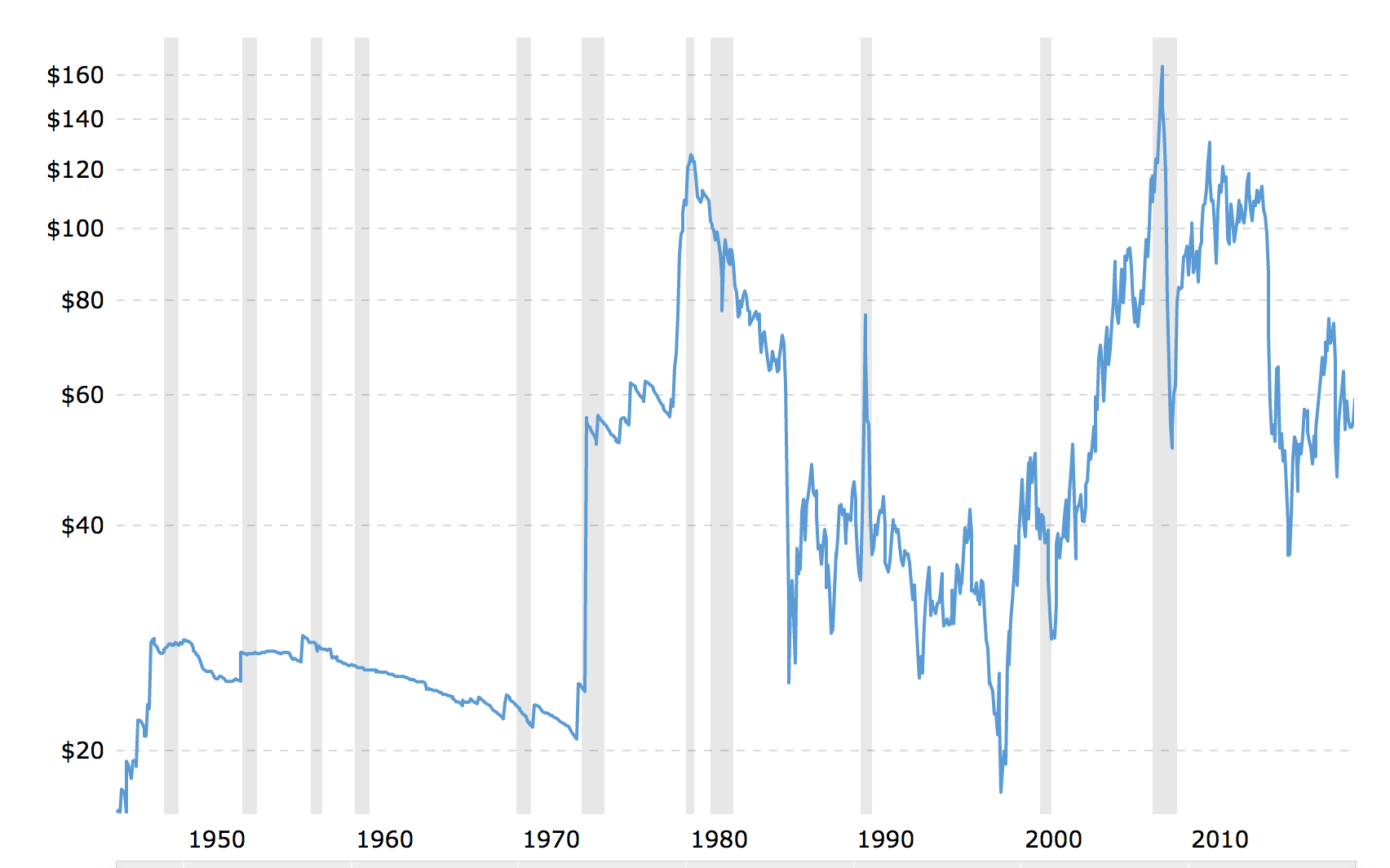

That August was the beginning of long disinflationary period that ended in May 2007. It gave a huge tailwind to financial asset prices and helped make the new neoliberal model, of denying workers real income gains but letting them binge on debt as a way to increase their standard of living, palatable. It was also a major driving force for financialization, which is increasingly decried by economists as a negative for growth. No wonder bankers revere Volcker.

Ironically, economists have deemed the Volcker and parallel Thatcher money supply experiments to be failures. Contrary to the persistent myth-making of Milton Friedman, money supply changes (and lagged ones) correlated with no macroeconomic variable. So it may not come as a surprise that William Grieder found, in his classic The Secrets of the Temple, that Volcker may have suspected as much. Greider provided evidence that Volcker was using money supply targets as an a cover to let interest rates rise vastly higher than would have been deemed sane he had stuck with the traditional central bank approach of targeting interest rates.

Another telling Greider tidbit was that during the time when Volcker was driving interest rates to the moon, Volcker would keep a notecard in a jacket pocket that tracked weekly construction wages. Volcker saw getting them to decline as a key metric that his policies were succeeding. He intoned: “I want unions to get the message.”

Some experts, such as Warren Mosler, point out that the underlying inflationary trends were dissipating even before Volcker launched his money jihad, as shown by oil prices peaking in 1979. Recall that Volcker became Fed chairman in 1979 and started implementing the “Volcker shock” of constraining money supply in March 1980. Thus there is a case to be made that inflation would have abated, particularly since the key practice that had helped reinforce it, widespread formal and informal cost of living adjustments, had been abandoned or weakened.

The suddenness of Volcker turning off his “kill the economy to save it” initiative wound up seriously damaging US manufacturers. Mind you, they had been feeling considerable heat from Germany and Japan in the 1970s. I recall a sense of despair and even desperation in the business press and among my business school colleagues (I went to HBS from 1979 to 1981) about the decline of US competitiveness. Some of it was that many US manufacturers, particularly automakers, were saddled with old plant that was less efficient than that of the foreign upstarts. Germany and Japan also had better infrastructure thanks to post-World-War II reconstruction.

That isn’t to say that far too many US companies were also afflicted with sclerotic management. There are famous stories from that era of GM execs having no idea how bad the company’s cars were because they’d be babied every day by mechanics while they were at the office. Big US manufacturers also often saw themselves as victims of unions who protected slough-off workers. That picture was challenges when Toyota, in a famed joint venture with General Motors called NUMMI, took over the operation of GM’s worst factory, which it had shuttered in 1982. Its workers had regularly called in sick or showed up drunk. Toyota re-hired the 85% of the former employees and let the union play a role in choosing managers. Toyota got the factory’s output to the average quality level of (then widely recognized as way better) Toyota plants.

But the aftershocks of the Volcker experiment put floundering US manufacturers on a faster decline, from which most never recovered. The dollar strengthened considerably and rapidly, which gave foreign manufactures a price advantage. In the 30 months of the super-strong dollar, US automakers lost market share sharply, and they never got it back. The impact was so strong that even the supposed free marketer Reagan Administration was able to secure the Plaza Accord of 1985, a coordinated G-5 effort to push the dollar down and in particular, the yen up.

Volcker remained an uber-inflation hawk, arguing for decades after his leadership of the Fed for zero inflation, an idea that would have most orthodox economists’ eyes rolling. Even though economists dislike inflation, they loathe deflation. If you accept the premise that the central bank is using interest rates to manipulate growth, zero gives you nowhere to go if you think you need to drop rates in a crisis (the US, unlike Europe, remains allergic to the idea of negative interest rates, and we’ve explained elsewhere why this is a sound view).

Mind you, MMT advocates also favor zero interest rates, but their approach is radically different. They don’t want money to play a role in managing the economy; they want to use a Job Guarantee to provide a floor for labor prices and help assure sound development, and use fiscal spending to further regulate activity. By contrast, Volcker was also adamantly opposed to deficit spending.

Volcker also stood for skepticism of bankers and his belief in the need for strong regulation, particularly of consumer products. He was vehemently opposed to money market funds, recognizing (as the crisis demonstrated to be correct) that consumers would incorrectly treat them as equivalent to government-guaranteed deposits. He also didn’t like that money market funds made it harder for the Fed to control credit (money market funds are big holders of commercial paper, which provide short term funding for corporations and later, off balance sheet vehicles). He also pooh-poohed financial services claims of adding special value, saying that the last innovation he’d seen in banking was the ATM.

Volcker’s brand image as a strict regulator led Obama to include him in campaign events in his 2008 run, leading many to assume that Obama would make Volcker his Treasury secretary (one scenario was that Volcker would serve only for a year until the financial system was stabilized and then hand off the job). Obama’s bait and switch with Geithner showed where the incoming President stood on bank. And if you had any doubts, Obama added insult to injury by relegating Volcker to heading a “do nearly nothing” committee.

But the idea that Volcker was actually tough on banks is considerably exaggerated. Consider, for instance, our write-up of a 2010 Volcker speech widely depicted as “blistering”:

Unfortunately, the reactions to Volcker’s speech say far more about politics and PR in the US than they do about what he actually said. Volcker’s comments were delivered in a moderate, occasionally perplexed tone. He was often candid and descriptive, far from “blistering.” And despite the Wall Street Journal headline, “Volcker Spares No One in Broad Critique,” in fact he left many targets untouched (bank pay, accounting chicanery, “free market” ideology, cognitive capture of regulators and the revolving door between regulatory positions and lucrative private sector roles, predatory behavior by financial firms). In fact, Volcker was a defender of traditional commercial banks, noting that they have special role via acting as depositaries and payment services, and complaining of how money market funds were encroaching on their turf and providing similar functions without having the same degree of oversight and capital requirements. He also spent a fair bit of his talk extolling the Fed as the logical party to serve as the lead financial regulator, while somehow missing that the central bank did a horrific job in the runup to the crisis and is chock full of monetary economists who have no interest in financial firms’ inner workings.

Indeed, Volcker actually said (and I am not making this up), that the mess in the economy was NOT the result of the financial crisis. His formulation is rather astonishing. He depicts the financial crisis as the result of real economy imbalances, as opposed to the build up of speculative excesses in a grossly undercaptialized, tightly coupled financial system (starts at 9:30).

But in saying that I don’t mean to blame the crisis on the regulators or even on the market. I mean, this crisis got so serious, it’s so difficult to get out of this recession because of disequilibrium in the real economy. You know the story…when the bubble in housing burst, then the financial system came under great pressure, you don’t blame it for originating the crisis, in fact, under pressure, it broke.

Huh? The idea that the real economy distortions produced the crisis. as opposed to deregulation led to excessive leverage in financial firms and were the primary cause of distortions in the real economy, is barmy. Contrast Volcker’s take with that of Meryvn King, Governor of the Bank of England in a 2009 speech:

Two years ago Scotland was home to two of the largest and most respected international banks. Both are now largely state-owned. Sir Walter Scott would have been mortified by these events. Writing in 1826, under the pseudonym of Malachi Malagrowther, he observed that:

“Not only did the Banks dispersed throughout Scotland afford the means of bringing the country to an unexpected and almost marvellous degree of prosperity, but in no considerable instance, save one [the Ayr Bank], have their own over-speculating undertakings been the means of interrupting that prosperity”.

Banking has not been good for the wealth of the Scottish – and, it should be said, almost any other – nation recently. Over the past year, almost six million jobs have been lost in the United States, over 2 ½ million in the euro area, and over half a million in the United Kingdom. Our national debt is rising rapidly, not least as the consequence of support to the banking system. We shall all be paying for the impact of this crisis on the public finances for a generation.

To put none too fine a point on it, King is the top central banker an a country where financial services constitutes a bigger proportion of GDP than the US, yet he does not hesitate to place blame for the crisis where it belongs, on the banks (and he is willing to eat crow for regulatory lapses). Volcker, by contrast, offers a critique which is hardly controversial, yet gives the industry a pass.

Similarly, Volcker was hauled out of mothballs to press for what is now called the Volcker Rule only after the Administration was on the back foot as a result of losing the old Ted Kennedy seat in Massachusetts to Scott Brown, ending the Democrats’ filibuster-proof majority. The Administration wasn’t keen to have him give even comparatively mild criticism of financiers while it was laboring mightily to bail them out while not reforming them.

And the Geithner Treasury was not all that happy with the narrow restriction of the Volcker Rule.

Volcker’s idea of limiting bank proprietary trading was sound, but as we discussed at length at the time, trying to separate customer trading from other trades was a flawed way to go about it. A financial firm will often take on a large position from a customer because it can do so at a good price; if it flattens its position relatively quickly, which is what the Volcker Rule would want it to do, it’s perverse to look favorably to selling to customers as opposed to other professional traders. We argued, based on input from former in-house risk managers, that this was one place where the notorious Value at Risk model would give regulators a good handle on whether a financial firm was holding unduly large, as in presumed speculative, positions.

Part of Volcker’s stature was due to his famously modest (one might even say cheap) habits and his personal integrity. He stayed at the Fed even though he was nursing a wife dying of cancer. People on Wall Street at the time thought he might quit because the chairman’s salary wouldn’t buy much in the way of nursing care.

Volcker was also slow to cash out, and even when he did, he became the Chairman of the boutique investment bank Wolfensohn & Co., headed by former Salomon Brothers partner, later World Bank head James Wolfensohn. I have no doubt he could have landed a much more lucrative post had he wanted to.

I met Volcker first on an over 90 degree day, when I was in a T-shirt and jeans in a vegetable market around the corner from my apartment. He was wearing a suit and tie and carrying a very worn denim bag. I approached him and told him I remembered from my days at Goldman how everyone had hung on the money supply announcement. He seemed pleased to have been recognized and politely said I was too young for that. I didn’t keep him much longer.

I next saw him at one of Amar Bhide’s book parties, a very small gathering. Volcker was expected to make only a brief appearance but stayed for about half an hour. Oddly, he wound up seated alone for a stretch with no one talking to him. I went over a chatted him up, feeling it was wrong for him to be neglected like that. We discussed some recent news, although for the life of me I can’t recall what precisely.

I ran into him again at some INET conferences, and engaged him briefly at each, and also saw him speak an the Atlantic Economy summit (this when one of the budget debates was a hot topic) and Volcker moralized about the horrors of debt spending. I had gotten sufficiently better versed in macroeconomics to be disappointed.

Volcker’s starchy manner, lack of pretentiousness, and skepticism of bank claims of virtue made him old school. But he played a central role in ushering a Brave New World that was nevertheless better for financiers and rentiers than everyone else.

I finally bought my first car in 1981after walking everywhere I went for 6-7 years, the cheapest car sold in the US at that time IIRC. A Toyota Tercel with nothing but a clutch and a gear shift. No radio, No AC. It was a good car that lasted a long time. The interest rate at the local bank on the $2500 I financed was 17.19%. Our first mortgage in 1989 was at 9%. Thanks, Paul Volcker! Vaya con dios.

In 1979 we were having a house built and as it neared completion the mortgage commitment that had been approved some months before was pulled because I didn’t have enough income for a loan at the then-current 11% interest rate. My income was just below what was required, and the bank had previously signaled rule could be bent but given the market tumult management suddenly decreed it be rigidly interpreted and enforced. My wife, who had been a kindergarten teacher before the first child came on the scene, had been a stay-at-home mom for eight years and intended to resume that career after our youngest, then four, entered school. However with a potential financial disaster staring us in the face she needed a job – any job – for us to avoid it. She saw an ad in the paper for a proofreader at a catalog marketing company about a mile from where we would be living and got the job. By the time the company was shut down twenty two years later because of senior management malfeasance, putting 4,000 people out of work almost overnight, she had risen to managing a group of about 35 artists and copy writers. She’s often said the only management training she’d ever had and all she ever needed was the OJT of teaching kindergarten.

You should write down that story somewhere at home. As a amateur family historian, I can tell you that such stories are priceless for future generations.

Good idea. My niece and I are what passes for family historians in our clan, which in our case is an especially difficult challenge because some of our ancestors were late breeders, and the paper trail is minimal. Hopefully future descendants will thank us.

The first financial bubble i’d ever seen was high 0 silver, away!

It all starts really around the time Volcker becomes Fed chief in August 1979 @ $9 per oz and within 6 months it’s almost $50.

There were lines of people wanting to sell their various holdings of silver to primarily coin dealers, and the tricky bit to the game was the brothers Hunt only wanted pure silver deliverable bars, so anything with an alloy needed to be refined, and the few refineries that could do the work were swamped, so everything that wasn’t pure sold for discounts of 30-40% back of spot on a wholesale basis as things got toppy, we’re talking it taking months to refine it into pure.

Ah, yes. The Hunt brothers* and the silver market.

https://priceonomics.com/how-the-hunt-brothers-cornered-the-silver-market/

The Hunt brothers were the catalyst for the great vacuum of silver, while the ‘We Buy Gold’ firms that popped up like weeds did their deed with the barbarous relic.

One day around 2011 I was driving in Glendale,Ca. and just for fun counted all the storefront places specifically buying old yeller, and there were 17 in the great gold rush in reverse.

Please, Yves, one question:I do remember as well (from Germany) how the decline of US manufacturing started during the Volcker era and the mad interest rates. You are surely right that Volckers obsession with inflation played the largest role. But I then wondered and I still wonder whether the interest rates were also due to Latin American debt. That is the interest rates being used to bring the Latinos to heel via the IMF. (Or to better fleeze them). The other thing I wonder about is whether there is a connection with Reagans insane expansion of the military budget. That is the goverment crowding out all other investment. What is your view?

1. My belief is that Volcker was entirely preoccupied with domestic inflation. Even now, when international capital flows are much greater, when other countries (India, Brazil, etc) complaining that uncoordinated changes in US policies lead to destabilizing capital flows in and out of their countries, the Fed has basically said (at different times) “We don’t agree” and “Not our problem”. However, the prospect of Latin American defaults blowing back to US banks led him to stop strangling the US economy sooner than he would have liked.

2. The “crowding out investment” is a myth, but your idea has merit via a different mechanism. Investments do not come from a limited pre-existing pool of savings. If you want to learn more as to why, please Google or Qwant “loanable funds fallacy” for details.

Government spending has a powerful effect on the overall economy and national priorities. So this level of spending would definitely distort the shape of the economy.

Thank you very much. Things are clearer. If you could please here a follow up question: Could one say that the mass of T-bills hitting the market at unbelievable rates naturally let investors disregard all other investment opportunities? Meaning rates for private enterprise was driven even higher as there was such a safe alternative? Or is that to simplistic?

Paul Volcker was my boss’s boss back in 1964-67 when I was at the Chase Manhattan Bank as its balance-of-payments economist. Thanks to the fact that I had learned speedwriting in college to take notes, and because my writing style was rather 18th-century then (making the speakers sound pretty elite), I was selected to take notes on the big economic talk-talk meetings.

Some time in the 1970s I was asked to drop off at the White House, and Marina von Neuman Whitman asked me what I thought of Paul.

“Well, after a number of people had given their views, Mr. Volcker would say, “You say … and you (another presenter) say …” He would state everyone’s position so clearly that each person thought he must agree with them.”

“That’s the person we want,” Marina said (laughing, as I remember).

Mr. Volcker had left Chase to join the Treasury for a few years, and then ha come back — not too frequent, an officer told me. He always bent over forward a bit as he walked, was always friendly.

I don’t remember a single thing he said or wrote at the time, however.

You’ve described any number of senior managers I’ve encountered – it does seem that for many an ability to convey the impression that they agree with everyone, along with a refusal to espouse any ideas beyond the very narrow management overton window of whatever the subject at hand might be, is an excellent strategy for failing upwards at speed – especially if you can do it with the confidence inculcated by an expensive education and the right parents.

Not so much a comment on Paul Volcker but on the Fed position in general: The headline I first read said something like “Paul Volcker, who stood firm against Congress’ entreaties to loosen the money supply”…. and I thought “You know, nobody elected him. Why do Fed Chairmen have such power?”

I guess that comes from being a Naked Capitalism and MaxSpeaks reader! :)

The misunderstanding of Volker is simply a narrow, and particular misunderstanding that exists within a massive cloud of misunderstandings that define the American peoples almost non-existant grasp of historical reality.

After nearly four hundred years of slavery, genocide, and rapacious looting, we saved the world from Hitler and Hirohito, declared ourselves, baptized in all that blood, a new and exceptional nation, a bright shining city on the hill.

We are innocent of all our wars because we didn’t realize we were being lied to, and we are innocent of all the CIA skullduggery because it was all a big secret we knew nothing about.

And it should go without saying that we are innocent of genocide and the sins of slavery because that was some other people, a long time ago.

Having no ability, or inclination for that matter, to face the truth, we wallow about in our ‘misunderstandings‘, and insist that we are innocent by virtue of our ignorance.

That is our all-embracing misunderstanding.

“…we saved the world from Hitler”: 80% of the destruction of Germany’s military was inflicted by Soviet Russia. Please give credit where credit is due.

…at a cost of some 15% of the Russian population. (The US WWII losses were 0.2%.)

One can easily read that phrase as one of the many intended to reflect then thinking of the typical American.

Exactly

Thanks for this very balanced assessment – it does show the importance of individual character (or lack thereof) in key positions of influence. He way well have had a lot of personal integrity, but it seems pretty clear that history* won’t be so kind as to his influence. While no doubt he was buying into a mainstream narrative at the time, his ideological pursuit of low inflation seems to have been particularly damaging in so many ways that go beyond straightforward economic measurements.

*real history, not the type Wall Street will try to impose.

I searched this thread, once for ‘ideology’, and then for ‘ideological’. Those words appeared just once each, one in Yves post, and the other in your comment.

It seems to me that in nibbling around the edge of the problem, and do not spend enough time on how central the problem of ideology is.

We are facing an enemy who has systematically nurtured a self-serving ideology in the guise of scientific fact, and that until recently that enemy has succeeded.

So they’ve not only damaged our understanding of economic reality, they’ve degraded our faith in the scientific method as well.

I remember Paul Volcker all too well. I had finished grad school in 1979, and the FL Right To Work/Serf job outlook/market wasn’t good. Volcker was already known as a right winger. He was part of the establishment that has controlled this country for ages. We are suffering under the worse of this bunch now.

Yours Truly finished an undergrad degree during the same year. The job market was $#@& for me too. And it remained that way for much of my working career.

So, no found memories of Volcker. None whatsoever.

From the description that Yves gave of him in later encounters, I have the impression of a person that served their purpose and was then dropped from any future roll when they did not want to play the game the entire way through. Just an impression mind. Not exactly a useful idiot but something along those lines.

“If you accept the premise that the central bank is using interest rates to manipulate growth, zero gives you nowhere to go if you think you need to drop rates in a crisis (the US, unlike Europe, remains allergic to the idea of negative interest rates, and we’ve explained elsewhere why this is a sound view)….”

Yes, it has been explained well that negative interest rates are a wrong turn, but that it is exactly why I think the USA is headed for negative interest rates.

Thanks for a balanced assessment and noting that Warren Mosler ( of MMT fame) , point(ed) out that the underlying inflationary trends were dissipating even before Volcker launched his money jihad, as shown by oil prices peaking in 1979.

yes, how we just aren’t tuned in to how the ground shifts; we keep assuming that nothing ever really changes.

In addition, worth noting the ruinous effect the Volcker Shock had on dollar-denominated African debt levels – been a while since I read up on it, but I believe it’s part of what necessitated the later Debt Jubilee, that Ann Pettifor spearheaded.

I always admired his ability in pursuing his true passion:

”The greatest strategic error of my adult life,” Paul A. Volcker says – and I feel sure, listening to his deep, booming voice, that the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board is going to talk about something momentous, like the decline of the dollar against the pfennig – ”was to take my wife to Maine on our honeymoon on a fly-fishing trip.” It cost him dearly, a lost decade of fishing. —Nick Lyons, The New York Times Magazine; May 3, 1987

Very interesting to read about Volcker like this. Thanks.

Whaaaaat? Where would interest rates be were the FED to get to zero inflation? A lot higher than zero, I presume. I suppose if that were the way things were today, there would be somewhere to go, rate wise.

Eclownomists dislike inflation and loathe deflation, which leaves zero as a happy medium.

Anyway, goods and services price inflation is mostly divorced from what changes in input prices are responsible for, in that pricing is whatever can be gotten away with in some markets. The price of insurance, rent, food always increased faster than boss’s increase in pay, so inflation is a detriment from this peasant’s point of view.

In economic parlance savers [tm] loath upper bound inflation and deflation in price mechanics, strangely or not sundry unwashed savers are not what is being discussed – bondholders are.

If you were wealthy enough to have taken a position on the DOW in 1980, the decade following Vollker was a veritable fun house. If you were looking for work a veritable outhouse. Funny how that works.

Yves, thanks for this post.

“The evil that men do lives after them;

The good is oft interred with their bones.”

― William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar

I can imagine Volcker was mistaken but not cynical in his outlook, a modern Andrew Mellon.