The press is finally becoming skeptical of private equity’s claims that it generates superior returns, demonstrated by a Monday Wall Street Journal story, Private-Equity Cash Piles Up as Takeover Targets Get Pricier1 and a Bloomberg article yesterday, ‘Peak’ Private-Equity Fears Are Spreading Across Pension World. This follows a Mark Hulbert piece in MarketWatch, whose title gave the misleading impression that it was just about the proposed KKR acquisition of Walgreens, when it was really a takedown of the prospects for private equity generally, starting with the subhead: No evidence that public companies perform better after being taken private.

What is striking is investors who have long been captured and desperate, are finally admitting that private equity’s key selling point looks to have hit its sell by date.

While we’ll recap both pieces, they curiously miss that the one of the big drivers of private equity’s success, that of the long-term decline of interest rates that started in 1982, is no longer giving the industry a big tail wind. Declining interest rates boost financial asset prices, with risky assets benefiting the most. Public stocks are the riskiest liquid assets. And what is even riskier? Leveraged equity, which is the exposure you get with private equity.3

We’ve been writing for years about how the private equity industry has not been earning enough to compensate for its additional risks. And has time has passed, the evidence that the returns are not adequate has only strengthened. For instance, Oxford Professor Ludovic Phalippou determined that since the crisis, private equity has not outperformed the stock market. Recall that private equity performance benchmarks for decades have stipulated that private equity needed to beat an equity index, which until recently was typically the S&P 500 index, by 300 basis points.2 In her Congressional testimony last month, Eileen Appelbaum independently confirmed Phalippou’s assessment, that measured on a public market equivalent basis, as opposed to using the misleading internal rate of return measurement, private equity has not outperformed stocks since 2008.

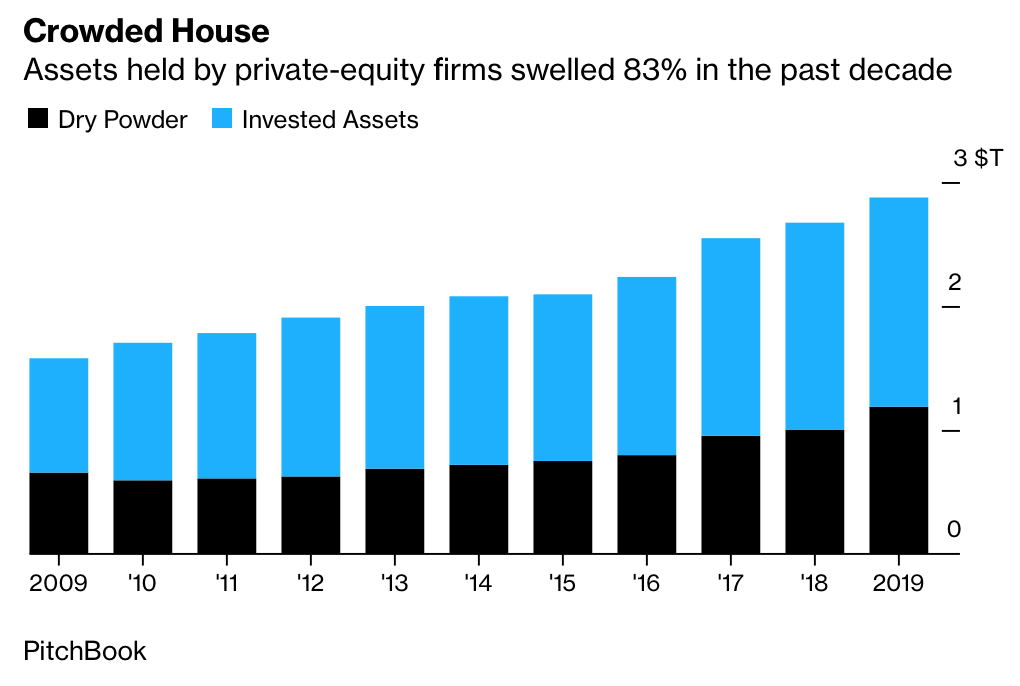

The Fed has made clear it’s not keen about negative interest rates, and in fact has been trying since the 2014 “taper tantrum” to ease its way out of its super low interest rate corner. Private equity returns have faltered not just due to the loss of the extra juice of a long-term trend of lower interest rates, but also desperate long-term investor reactions to negative real yields, which deprived them of safe but profitable long-term investments as a core component of their portfolios, and forced them to put more money on “reaching for yield” strategies like private equity. Since 2004 the share of private equity has more than doubled relative to the global equity market. So the end of return tailwinds has been exacerbated by too much money chasing too few deals.

It is hardly news that private equity valuations have been at stratospheric levels for years. CalSTRS’ Chief Investment Officer Chris Ailman described private equity deals as “priced almost to perfection” in 2015 and concluded: “So it’s a tough time to make investments and hope we make money.”

The Wall Street Journal describes how private equity firms are sitting on a lot of what the industry calls “dry powder,” or committed funds that have yet to be invested.We’ll recap some of the key points in a bit, but the bottom line from the Journal is that the funds are displaying investment discipline because, save for a few sectors, it’s hard to find attractive deals as a result of prices generally being at record levels.

While this is true as far as it goes, this narrow framing unfortunately misses the real story, which is that this phenomenon is yet more evidence of the deteriorating prospects for private equity. The Bloomberg article was far frontal, discussing how pension funds are fretting over faltering private equity returns, when they’d mistakenly pinned their hopes for salvation on them.

The Journal tries to put a pretty face on this picture. But not putting money to work creates two problems. The first is that investing money more slowly will hurt returns as measured by the misleading internal rate of return, and properly measured, would hurt actual returns, since investors will have to park a significant portion of the committed but yet uncalled capital in liquid investments. Second is that investors will also fall short on their asset allocations for private equity. From its article:

The aggregate value of U.S. buyouts fell 25% year to date through October, compared with the same period a year earlier, according to data provider Preqin. Deals totaled $155.2 billion during the first 10 months of the year—the lowest since 2014.

The restraint buyout firms are showing suggests a level of discipline that wasn’t present during the last market peak in 2007, when they struck $365.9 billion worth of deals in the U.S. Many of the companies they bought then struggled during the ensuing global financial crisis, and a number have filed for bankruptcy protection.

The drop in deal activity comes as private-equity firms’ unspent cash dedicated to North American buyouts reaches a record $771.5 billion, up nearly 24% since the end of last year and more than double where it stood at the end of 2014, Preqin data show.

The article tries to find cheery facts. Deal volume is not down, which suggests it’s the big deals where most money is put to work that is flagging. It plays back the sales talk of some of the largest firms as to how they are supposedly finding attractive sectors, and also highlights niches like business software where it’s supposedly possible to find buys.

First, private equity returns are reported on a one-quarter lagged basis. Correcting them to the proper quarter takes away most of the fictive differentiated return profile.

Second, private equity firms have been established to lie about their valuations at predictable times: when raising a new fund and during bear equity markets, and late in a fund’s life, when most of what is left are dogs that need to be written down. Correcting valuations for these misrepresentations would further tighten the correlation.

However, a further complicating factor is that borrowing has become more stringent and pricey too.

The Bloomberg article, by contrast, focuses on investor desperation. Why they are so late to wake up and smell the coffee is beyond me. Industry leaders have been warning for years that returns were likely to fall. That’s one reason they’ve been trying to push into retail, since they’d be dazzled by the chance to finally get past the velvet rope and invest in private equity…because they are the dumbest money.

Similarly, another big warning sign has been the recent fad of longer-dated funds, branded as “Warren Buffet-style investing”. If you are tying up your money longer, you should expect an even higher premium over public stocks than the historical rule of thumb of 300 basis points for the greater illiquidity risks. Yet investors were told to expect lower returns than for traditional private equity. Huh?

The Bloomberg piece has an even better “dry powder” chart:

Globally, the outperformance of PE over the S&P 500 fell to 1.07 times in 2017 from 1.69 times in 2001, according to data from PitchBook….

Calstrs chief investment officer Christopher Ailman is uninspired and under-invested. The second-largest U.S. pension had 9.3% of its $242.1 billion of assets in private equity as of Sept. 30, an allocation it plans to raise to 13% eventually. But Ailman is in no rush.

“Everybody is trying to chase what they perceive as the cream of the crop in private equity,” he said in a Bloomberg TV interview in November. “The median private equity portfolio return or GP return is usually actually equal or less than what you can get in public stocks.”

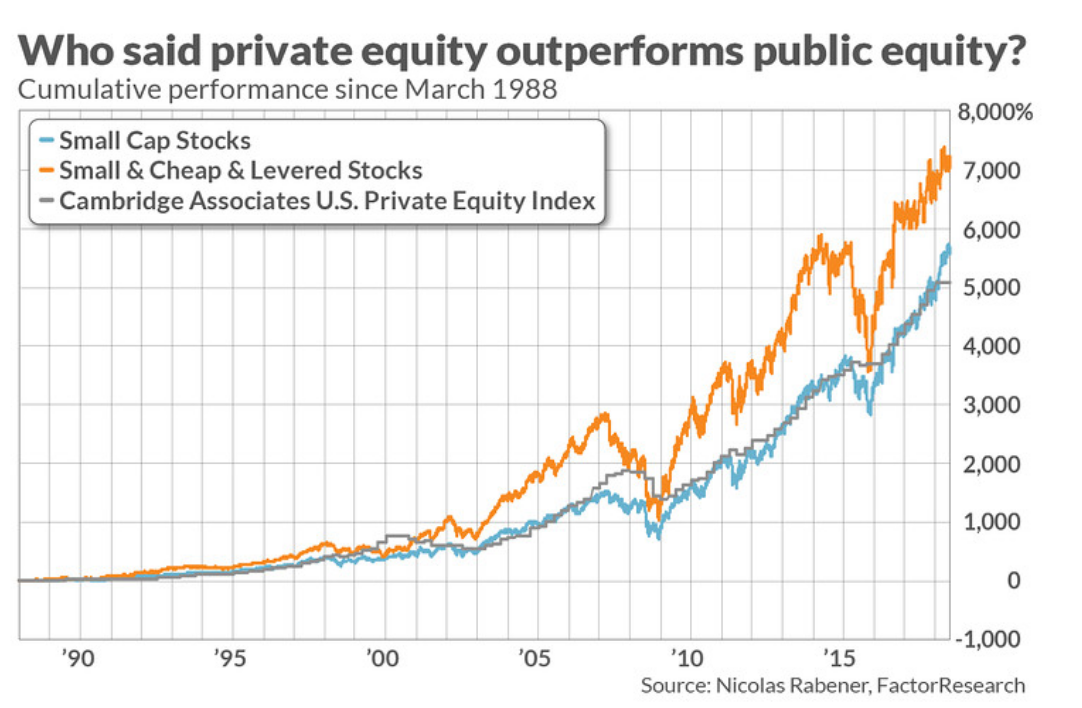

This is borne out by findings from Nicolas Rabener. The managing director of FactorResearch created an index of the smallest small-cap stocks and discovered in research last year that they performed in line with the U.S. Private Equity Index.

However, the article bizarrely praises CalPERS for gaming its benchmarks so as to pretend private equity returns aren’t deteriorating:

California Public Employees’ Retirement Systems reported its PE portfolio delivered 7.7% in the fiscal year through June 2019, down from 16.1% in the previous period. The pension giant foresaw a future of shrinking private-equity earnings two years ago, when the board cut targeted margins above the FTSE All World All Cap index to 150 basis points from 300 basis points.

It would have been nice if someone had sent the memo to the House Financial Services Committee hearing on private equity last month. Republican and money-captured Democrats kept thumping on returns, refused to consult with the one expert in the room, Eileen Appelbaum, and instead kept pumping Wayne Moore of LACERA for the factoid that historically, private equity had been the fund’s best performing asset class. Someone needs to remind them that the past is no predictor of future performance.

____

1 As too often occurs, the headline is misleading, since it suggests that private equity firms have hoards of investor cash sitting around. Investors in private equity firms, unlike other types of fund management, do not send money when they invest in a fund. They instead agree to send money, usually in five to ten business days, when the private equity fund makes a capital call to investors so it has the equity capital it needs to close on a deal. Investors also agree to pay management fees on a set schedule.

2 Phalippou has pointed out that many investors have switched to other stock indexes because the S&P 500 has been doing better and other indexes are more permissive. From e-mails in 2017:

Have you noticed a change over the last two years? From mid 2000s to mid 2010s, people were always comparing PE returns to that of the S&P 500. Over the last two years it is always MSCI world. Guess why? Because the S&P 500 has been doing very well over the last three years, unlike the MSCI world index.

Phalippou did not need to point out the implication: making the benchmark easier to beat also increases the odd of staffers at limited partners getting performance bonuses.

3 Some loyalists will try claiming that private equity returns do not covary much with public equities. This is false, or more accurately, is true only due to bad accounting.

Yep! To your point about other stock indexes as measurements: the skankmiester PE guys who have burrowed into my pension fund claim an 11.3% return on assets over 10 years. This, of course, based upon their own secret measurement sauce. It allows them to claim a sizable bonus because they exceed the agreed upon benchmark. Now, if our trusty public servant had, between cigarette breaks, simply invested in the Russell 3000 over the last 10 years we would have had a return of 14.7%. Where is RICO when you need it.

i don’t really have a squirrel in this race(no money=no “investments”–save for TRS, which is pretty opaque and subject to my general distrust of texgov :https://www.trs.texas.gov/Pages/active_member_annual_statement_guide.aspx)

…so i’m hardly savvy on this subject, although i tend to regard most of this sort of thing as pretty much 3 cups and a pea and/or entirely imaginary.(my idea of “investment” is things like fruit trees)

nevertheless, reading through, i’m reminded again of the utter necessity of Growth for all this to even pretend to function.

the california guy they quote a couple of time appears to indicate that the PE market has topped….ie: nobody expects further growth, so no one;s buying for higher numbers, so the reason for doing all this is really no longer there.

this feels to me like another facet of a larger problem…which includes what’s going on(or fixin’ to) in the Permian with all the fracking…no profit, but burning through whatever pools of money they can get their hands on, until they can’t, when it goes belly up of a sudden.

i guess my question(remember, i’m pretty heavily medicated, atm,lol) for the resident badassery: how prevalent is this phenomenon of “irrational exuberance” bumping up against more or less physical barriers(like the limits of surface tension in an actual bubble)?

I can practically go onto the porch and listen to the highway, a mile or more distant, and have an idea of how things are going in the oil patch,lol…but the ur-salesmen(bear and bull, notably), hypercomplexity, etc obscure what’s happening elsewhere, unless one devotes more time and brain than i;m willing in order to study such things.

is there an Index for that?

You do have a dog in this fight because your local and state taxes are funding public employee pensions. Shortfalls in projected performance results in combination of higher taxes and when permitted, pension cuts. In California and Illinois, government bodies backstop the pension, so they can’t be reduced. They can only be cut back on a going-forward basis.

i’m of the Ow Holmes school(“i like paying taxes…”)

that said, i get what you’re saying, absolutely.

but none of the people in charge of..say…TRS(teacher retirement, Texas), let alone the Texas Lege, give a fly’s butt what i think about the running of their fiefdoms. they have “experts” who are just as enamoured of the latest thing from on high as they are.

so it’s a dog, but several times removed from the actual race.

my dog and i are way over here, in a pasture.

there are fences and moats and much bigger dogs and such.

“the rich do what they can, the poor do what they must”(until the rich inevitably make a fatal error and collapse the very thing their wealth relies upon)

i’ll be over here, in the pasture, with the dog.

Add to this the more general fact that as the boomer cohort retires, they will slowly go from investing (both directly and through pension funds) to pulling money out to live on. That will place downward pressure on investments that is only counteracted by the concentration of ever-more money in the hands of those wealthy enough to invest. That concentration too, may be reaching peak. All of which will mean that the special sauce of more leverage may stop working with a bang, just as it did for mortgage bonds.

Reversion to meanness, accompanied by nasty, brutish, short and a whimper.

Should include in that sequence the expected and obligatory and usually fruitful appeal to on-board, bought-and-paid-for, legitimizing institutions with keys to the MMT locker. Aka “bailout,” which ought more accurately to be called “bail-IN.”

Also — that word “disinflationary.” Is that a comforting euphemism for that dreaded “deflationary”?

Hedgefundy folks became ‘green’ hedgefundy folks by buying up bunches of solar pv farms. I have always wondered what happens to those valuations if inflation/interest rates goes the other way.

I have been told by industry folks that they always made sure that the PURPA (Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act) mandated contracts matched up with the investor contract timelines, but Duke Power (at least) has been pushing back hard on the length of the PURPA contracts.

As a Head of a Performance department (many years & roles ago), I once tried to figure out what the returns were that the PE guys (in a sealed room, by the by) were giving me. They are finger in the air (based on general equity returns!) with some added dreamwork and the rubbish that is IRR (Internal Rate of Return). The CFA Institute (the “voluntary” GIPS or Global Investment Performance Standards) and the SEC should really crack down on this nonsense as it’s completely misleading. The SEC has nailed firms for how they report GIPS “compliant” returns and this is a very target rich environment.

“It is hardly news that private equity valuations have been at stratospheric levels for years. CalSTRS’ Chief Investment Officer Chris Ailman described private equity deals as “priced almost to perfection” in 2015 and concluded: “So it’s a tough time to make investments and hope we make money.”

I don’t know, but that sounds like a demand problem as much as a stock price problem.

Isn’t this classic inflation? Too much money, not enough assets to buy; the price of assets too expensive. This is a more interesting kind of demand – it is profit demand which is created by… profit. But, tsk tsk, you can’t demand profits when your chosen economic ideology has just screwed the entire world. Pension funds should invest in-state to create jobs and repair both society and the environment. If California and Massachusetts can ban gas/oil furnaces and appliances the pension funds should be able to invest in a better decentralized grid and electric appliances, factories and workers. There’s no place left for PE because it extracts all the value; it doesn’t create it. I think there’s a metaphor here somewhere. ;-)

Well said Susan. I hope your’s is not a voice crying in the wilderness.

QE, $250 Trillion worldwide debt and interest rates driven to (and in Europe, through) the floor. Welcome to Alice in Wonderland economics, sailing into uncharted territory.

I think this is an example of the fact that roughly speaking at least, the efficient market theory is correct. The driver for p e, like mutual funds and other professionally managed funds, is not return for investors but opportunity for looting by the principles.

I don’t mean necessarily illegal rewards, but outsized rewards available due to the hype and investor gullibility.

You shouldn’t look for motives of institutions, which have none, but motives for individuals.

Another example is not-for-profit businesses. Executives can pay themselves extremely generously and count is as a business expense, not as profit.

Only people have motives !!

Lotsa money to buy public firms and loot them. No shortage of dough to pour into money losing fracking. Plenty of cash to finance arms and wars. But cannot afford healthcare, education or alternative energy. It is beyond me how capitalism can be defended.

More Alice in Wonderland economics.

It used to be that the environment was threatened and sacrificed in favour of profit: the Holy Dollar. Now we have fracking not only wrecking the environment and threatening or polluting groundwater, but losing money too.

How low can we get before we collectively make change for the better ?(survival even)

To repeat a very important para (too often discounted in its importance to all of this, imo):

While we’ll recap both pieces, they curiously miss that the one of the big drivers of private equity’s success, that of the long-term decline of interest rates that started in 1982, is no longer giving the industry a big tail wind. Declining interest rates boost financial asset prices, with risky assets benefiting the most.

Now that interest rates have effectively bottomed out, there’s not much way to move/redirect business money formerly paid in interest into PE fees. This chart of historical stock market price/earnings (p/e) ratios is interesting.

https://www.macrotrends.net/2577/sp-500-pe-ratio-price-to-earnings-chart

Thanks for this post and your continued reporting on Private Equity (PE) and pensions.

I know this is a bit simplistic, but if interest rates went up, it could expose highly leveraged companies and increase the number of prospects for take over, or bankruptcy (and eventual take over). Isn’t that the whole fundamental thesis of why there is so much capital on the side for PE and also Distressed/Special Situation Credit Funds?

Worth also noting that the PE model used to be one of buying public companies fixing them and then re-listing them, the current model is buying private or public companies and then adding on various transactions with PE firm insider opcos to bleed out all the newly borrowed funds to line the PE companies principals pockets, mark up the valuations to levels they can never be sold at, tell the pension funds they are making 20% IRR on the investments and ask for more funds …

The whole Ponzi will collapse at some point and then the pie in the sky valuations and related party transactions will come to light, of course at that point the pension fund trustees rather than the PE principals will take all the heat ….

Just to follow up on Flora, the true cause of high equity values is institutional wage repression over five decades since 1970. To a tolerable approximation, Tobin’s q or the ratio of stock market valuation to the replacement cost of capital is equal to the ratio of the corporate profit rate net of depreciation, interest costs, and taxes to a real interest rate. That is, q approximately equals the net profit rate capitalized by interest cost. Institutions (union-busting, right-to-work laws, globalization, fissuring labor markets, etc.) have held money wage growth below productivity growth. The consequences have been higher profits, slower inflation, lower interest rates, and a 400% increase in q. Private equity has been a major beneficiary.