Yves here. This analysis shows that generalizations about trade are fraught. While most of the developing countries studies showed both increases in incomes and inequality, some had the best of all possible worlds, of higher incomes and a decline in inequality, while some showed losses in income overall and/or among the poor.

One frustration is that this paper does not acknowledge that more unequal societies score worse on social indicators, such as happiness, crime rates, and health, even of the rich. Thus it would have been helpful to know more about the typical severity of the rise in inequality where that occurred.

By Erhan Artuc,Senior Economist, World Bank, Guido Porto, Associate Professor of Economics at the University of La Plata and Bob Rijkers, Senior Economist in the Trade and International Integration Unit of the Development Research Group, World Bank. Originally published at VoxEU

Questions about who benefits from free trade – and at what cost – have resurfaced as part of the backlash against globalisation. This column uses data from 54 low- and middle-income countries to show that in a majority of cases, trade liberalisation increases both incomes and inequality. Most of these trade-offs resolve in favour of liberalisation; despite exacerbating income disparities, trade liberalisation creates overall social welfare gains.

The recent backlash against globalisation and a resurgence of protectionist tendencies have renewed interest in the distributional impacts of trade policy (Baldwin et al. 2017, Fajgelbaum et al. 2019). In developed and developing countries alike, trade liberalisation has left large swaths of the population jobless (Autor et al. 2013, Kovak 2013), despite boosting growth and innovation (Coelli et al. 2016). Moreover, trade is often alleged to exacerbate inequality. Should free trade be opposed on inequality grounds?

In a new paper (Artuc et al. 2019a), we answer this question by providing estimates of income gains and inequality costs resulting from unilateral import tariff liberalisation for 54 low- and middle-income developing countries. Inequality considerations are especially important in these countries given that substantial shares of their populations either live in poverty or are at the brink of falling into it. Whether a trade-off exists between the income gains and inequality costs of import tariff liberalisation is thus a crucial question.

How much each household in a given country gains or loses after trade liberalisation depends on how much tariff cuts reduce prices, and how these price changes impact different households. As consumers, households benefit from lower prices; but as income earners, lower prices imply lower profits and wages. Because households consume different types of goods and have different income portfolios, trade impacts are likely to vary across the income distribution. Poor households, for instance, tend to spend a larger share of their income on food products than do rich households, and derive a lower share of their income from wages.

Painstakingly harmonising household survey data with trade data allows us to quantify, to first order, how each household is affected by liberalisation-induced changes in the prices of a disaggregated and representative set of goods.

The evidence for income gains from trade is overwhelming: Trade liberalisation creates gains from trade in 45 countries, and losses in the remaining nine. The losses arise from governments losing tariff revenue. Average income gains across all countries are 1.9% of real household expenditure on average, driven to a large extent by lower food prices.

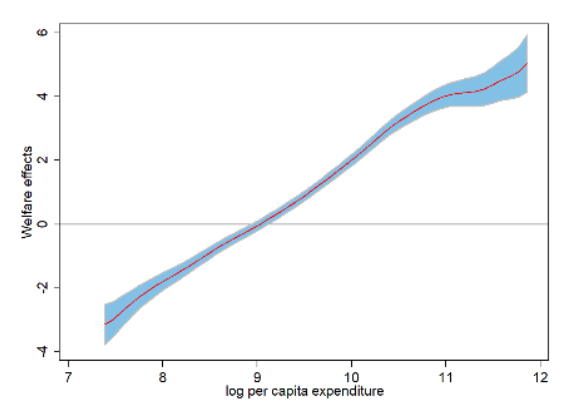

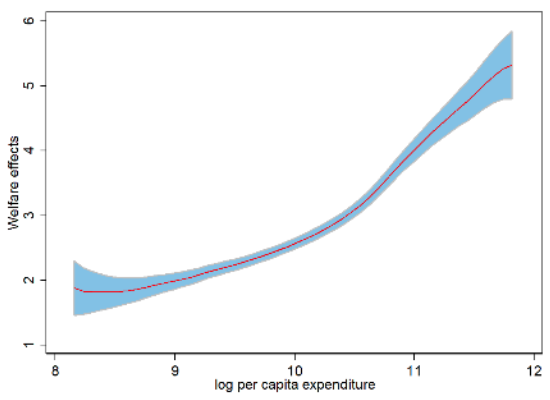

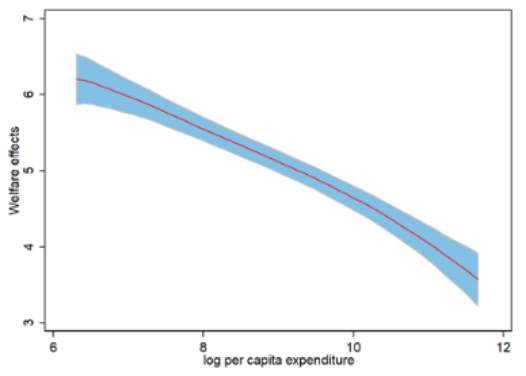

Yet, these gains come at the expense of exacerbated inequality. In 37 countries, the top 20% of the richest households would gain more from liberalisation than the bottom 20%. Examples include Benin and Uzbekistan, where rich households gain more than poor, as shown in Figure 1, which depicts average income gains against log per capita expenditure in the status quo. In Uzbekistan, households throughout the income distribution gain on average, but rich households gain more than poor. In Benin, poor households lose real income while rich households gain. In 17 countries, liberalisation would reduce inequality; in the Central African Republic, for instance, liberalisation disproportionately benefits the poor.

We then assess how estimates of the gains from trade change once we take into consideration impacts on inequality, allowing for different views on how inequality-averse one should be. Trade-offs arise when income gains are accompanied by increased income inequality.

In a handful of countries, there are no trade-offs; trade both improves incomes and reduces inequality (or leads to both a reduction in income and worsening inequality). In the Central African Republic, for example, the gains from trade are amplified depending on the magnitude of amplification increasing with inequality aversion.

In the overwhelming majority of countries, trade-offs arise. In Uzbekistan, for example, trade improves incomes but worsens inequality. Factoring in the impact on inequality reduces the inequality-adjusted gains from trade, but they never turn negative; liberalisation would be associated with higher welfare. This is not the case for Benin. When inequality aversion is low, liberalisation is preferred; when people care a lot about inequality, the status quo yields higher levels of social welfare. Put simply, whether liberalisation is desirable depends on how much one cares about inequality. Across countries, the majority of trade-offs resolve in favour of liberalisation; even though trade exacerbates income disparities, it brings social welfare gains.

Figure 1 The distribution of the gains from trade

A1 Benin

A2 Uzbekistan

A3 Central African Republic

These results underscore important heterogeneity in the impact of trade policy, both across countries and within countries across households. Not everyone gains from trade, and some households lose significantly. The results also pose a puzzle, for they suggest that countries would be better-off if they were to liberalise. Yet, they choose to implement trade protections instead. Understanding why is an important topic for future research.

Authors’ note: In an accompanying paper (Artuc et al. 2019b), we introduce a simulation toolkit to calculate changes in income distribution of households following specific tariff shocks that can be entered with a user-friendly web interface. The toolkit and underlying data are available at https://www.worldbank.org/en/research/brief/hit.

See orignal post for references

One thing the EU is doing now, re Brexit, is warning the UK that it will take a very long time, after January 31st, to come to a new trade agreement because the EU, unlike some individual country, must have all those separate agreements in order to prevent an “unfair trade advantages” for the UK if the UK does not qualify on various restrictions to do with adequate social welfare; wages; no mercantilist practices with other countries I assume, and on and on. So the EU is in effect imposing behavioral tariffs on the UK to protect the EU from any race to the bottom the UK might have in the works. The EU is a liberalized trade organization but as a block they are anti free trade.

Just wondering about this analysis – was any research devoted to the need for individual governments having to step in and provide social welfare because free trade impoverished so many of its citizens? Doesn’t sound like they wanted to go there.

I would think that the nature of the products the “developing” country is exporting, and importing, would play an important factor in the effect trade has on income gains and inequality. For example, let’s say you have one subsaharan African country that primarily exports coffee, and another that is exporting rare earth minerals from recently-discovered deposits. The former is less likely to experience disruptive social changes, as trade is taking already-existing subsistence plus farming and scaling it up. The latter is going to pull people where they had been living to the deposit sites, and the work itself may induce greater health costs. Going the other direction, if imports are more likely to be luxury items, that will make the populace less dependent on imports, and ergo less beholden to foreign capital, than if imports are displacing formerly domestically produced essentials, like with Venezuela and basic grain foods.

Very wrong actually. Sub Saharan countries that export coffee (e.g. Rwanda) are so much better off than those (like Congo) that discovered precious minerals. And for countries that primarily import luxury items (e.g. Nigeria) the whole country depends mostly on imports for even the basic things.

There is something to be said for production and consumption but it’s not this

Such analyses are ridiculously simplistic as they do not consider the dynamic development of an economy, i.e. the ability to upgrade industrial and service sectors. Opening up to a much stronger set of competitors will crush the ability to develop these. That is why NO country has successfully industrialized without trade barriers to protect infant industries:

–

– Thats how the US developed: read “America’s Protectionist Takeoff 1815-1914” by Michael Hudson

– Thats how the Asian tigers did it, and how China is doing it – read “Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism” by Ha-Joon Chang.

– The British textile industry (the base of its industrialization) would have been destroyed by much better quality Indian imports without very high tariffs protecting it – and then the British Empire explicitly destroying the Indian textile industry.

Endorsed — I see where we’ve had similar reading lists …

Poor households, for instance, tend to spend a larger share of their income on food products than do rich households, and derive a lower share of their income from wages.

Have I missed something, or is this a typo?

1.9% i.e.

This was the first reference to income (on Google) that I found and was for the US.

So, 1.9% seems small historically (is year on year—tho probably not?), framed anyway by change in the US (& elsewhere) if we’re trying to explore standard of living and fairness, & that as well includes comparisons between wealthy & developing economies.

Standard of living might also include broad questions of welfare (& quality of life?) as perhaps alluded to by Yves in her intro.

More households benefitted more from a closed US economy than an open one. Its interesting that mainstream economists don’t know are have no interest in this interesting historical ‘experiment’ by a very large economy. The extremely open economy (to capital and people btw) of the US circa 1870 to 1930 was really really bad for the 99% including the large number of immigrants amongst them. The pretty closed economy of Smoot Hawley (1930’s) to 1975 was pretty good for the 99%.

The rest if the think tank discussions is a bunch of econometrics in search of a question.