Yves here. This post describes how much of the economics discipline has settled on a neat, plausible, and wrong explanation of secular stagnation. The only good news is at least pretty much no one buys Larry Summers’ theory.

By Servaas Storm, Senior Lecturer of Economics, Delft University of Technology. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

The spectre of stagnation

A spectre is haunting the U.S. economy — the threat of stagnation. The anaemic recovery of the American economy after the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09 looked uncomfortably similar to what Alvin E. Hansen (1939, p. 4) in the late stage of the Great Depression had called “sick recoveries which die in their infancy and depressions [….] feed on themselves and leave a hard and seemingly immovable core of unemployment.”

Not surprisingly, therefore, interest is once again growing in Hansen’s ‘secular stagnation’ thesis which stated that an economy could experience persistent stagnation as a result of a structural shortage of aggregate demand. As is all too well known, Lawrence Summers (2013, 2015) played a big role in reviving Hansen’s original idea, but he did this with a distinctly pre-Keynesian twist. In Summers’ analysis, an ageing population, heightened income inequality and a large inflow of foreign finance, by raising savings, created a structural excess supply in the market for loanable funds; this ‘savings glut’, so the argument goes, pushed down the interest rate to its zero-lower bound. However, because, according to Summers, even a zero interest rate failed to remove the savings excess, the macro outcome has been a structural demand deficiency — and stagnation.

Summers’ ‘zero-lower-bound explanation’ of the demand shortage and stagnation splendidly failed to persuade the profession. Neither did it convince policy-makers. One reason is that modelling the financial system as a loanable funds market operating in a ‘corn economy’ is, as argued by Bofinger 2020, empirically misleading and practically dangerous: monetary economies and modern financial systems, as Keynes realized already in the 1930s, work differently — lending by money-creating commercial banks is not constrained by available savings (deposits) and business investment is overwhelmingly driven by (expected) demand (see Cynamon and Fazzari 2017; Kopp et al. 2019) rather than by changes in the interest rate; I have argued this before (Storm 2017 and Storm 2019), writing in the spirit of Samuel Beckett’s famous lines (from the 1983 story Worstward Ho): “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

But there is a second reason why Summers’ zero-lower-bound explanation of the demand shortage and stagnation failed to make the cut: evidence suggests that the U.S. is not suffering from a shortage of demand: the growth rate of actual output during most of the 2000s has been staying close to potential output growth and even has exceededpotential output growth since 2010.

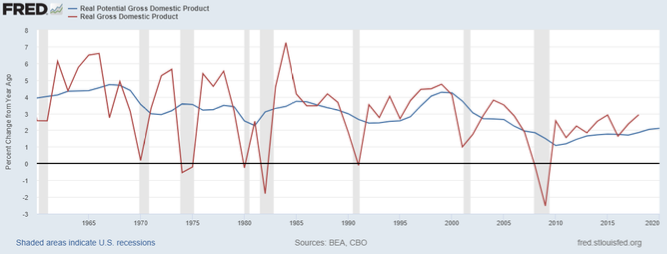

This is shown in Figure 1, which presents the growth rates of actual and potential output of the U.S. economy during the period 1960-2018. The figure shows a rather steady decline in potential growth — from more than 3% per year in the 1960s and 1970s to less than 2% per year during 2007-2018. Actual growth can be seen to fluctuate around potential growth, and to follow the downward trend. Indeed, virtually all empirical studies of both actual and potential growth of the U.S. show a remarkable slowdown, which started well before the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-09 (Fernald 2014; Storm 2017; Kiefer et al. 2019; Fontanari et al. 2019). Most observers conclude that it must have been declining potential growth which forced down the rate of actual (demand-determined) growth, because they have learned to believe that while demand does affect actualgrowth, it does not and cannot influence potential growth – the latter is said to be completely determined by ‘demography’ (labor force growth) and ‘technology’ (productivity growth).

Figure 1: Potential and actual economic growth: the U.S. (1960-2018) Source: FRED Economic Data; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GDPPOT#0

The Slumber of Decided Opinion: Supply-Side Secular Stagnation

Hence, in its modern incarnation, secular stagnation is not so much a matter of a deficiency of demand (as was Hansen’s view), but a symptom of deep structural problems on the supply side of the economy (Fernald 2014; Furman 2015; Gordon 2015). An ageing labor force and demographic stagnation constitute a first supply-side problem. But the real problem is the alarming steady decline in total-factor-productivity (TFP) growth, the main component of potential output growth. Diminishing TFP growth is taken to reflect a deep-rooted technological torpor, which lowers the returns on investment and hence pushes desired investment spending down too far. This, in turn, is argued to have lowered the growth rates of both potential and actual GDP. Thus, the conclusion must be that the U.S. is ‘riding on a slow-moving turtle’, and ‘there is little politicians can do about it’, as Robert Gordon (2015, p. 191) expressed it.

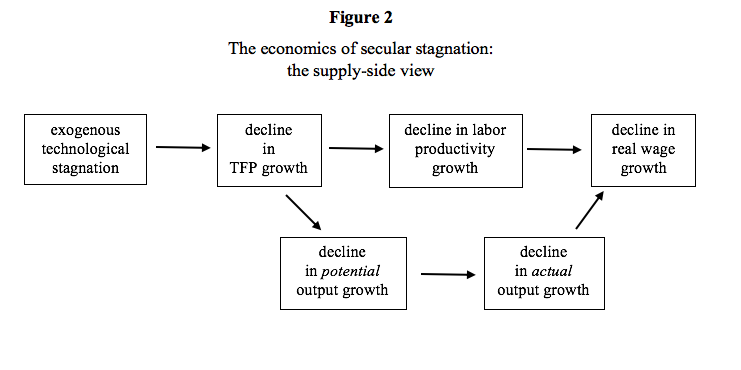

In the accompanying paper and using standard growth-accounting schemes, I present empirical evidence on the secular decline in aggregate TFP growth for the U.S. economy (1948-2015) and on the main components or drivers of this decline. I find that the secular decline in TFP growth in the U.S. is driven almost completely by the long-term slowdown of labor productivity growth and/or the secular decline in real wage growth. In the supply-side narrative, fading labor productivity is supposed to have forced down real wage growth. This ‘decided opinion’ is illustrated in Figure 2: the technological torpor captured by the exogenous decline in TFP growth leads to lower labor productivity growth, which in turn forces down real wage growth. That is, in line with the marginal productivity theory of income distribution, neoclassical supply-side ‘intuition’ holds that real wage growth ‘follows’ exogenous productivity growth, because profit-maximizing firms will hire workers up until the point at which the marginal productivity of the final worker hired is equal to the real wage rate. However, as John Stuart Mill observed long ago, “the fatal tendency of mankind to leave off thinking about a thing when it is no longer doubtful, is the cause of half their errors” and Mill appositely warned about the “deep slumber of a decided opinion”.

Demand-driven secular stagnation

The ‘supply-side intuition’ does not allow for any influence of demand factors on the secular decline in productivity growth and squarely blames the decline in potential growth on the slowdown of exogenous technological progress. However, the problem with this simple ‘intuition’ is that it is wrong. There are sound theoretical reasons, and there is robust empirical evidence, to blame (a substantial part of) the long-run decline in productivity growth on stalling demand growth (Storm 2017; Girardi et al. 2018; Fontanari et al. 2019). This goes against the deep-rooted theoretical belief system which maintains that long-run trend growth is determined by ‘technology’ and ‘demography’ and can be separated from short-run fluctuations of actual demand-determined growth around this trend. Generations of macro-economists have been educated to believe that ‘Keynes’ holds only for the short run, whereas the inexorable supply-side factors ‘demography’ and ‘technology’ govern the long-run. Generations of policymakers have been wont to using notions of ‘potential output’ and ‘output gaps’ to anchor macro-economic, and especially monetary, policy — notions which are derived from exactly this belief that demand does not matter in the long run ( Cynamon and Fazzari 2017; Girardi et al. 2018; Fontanari et al. 2019).

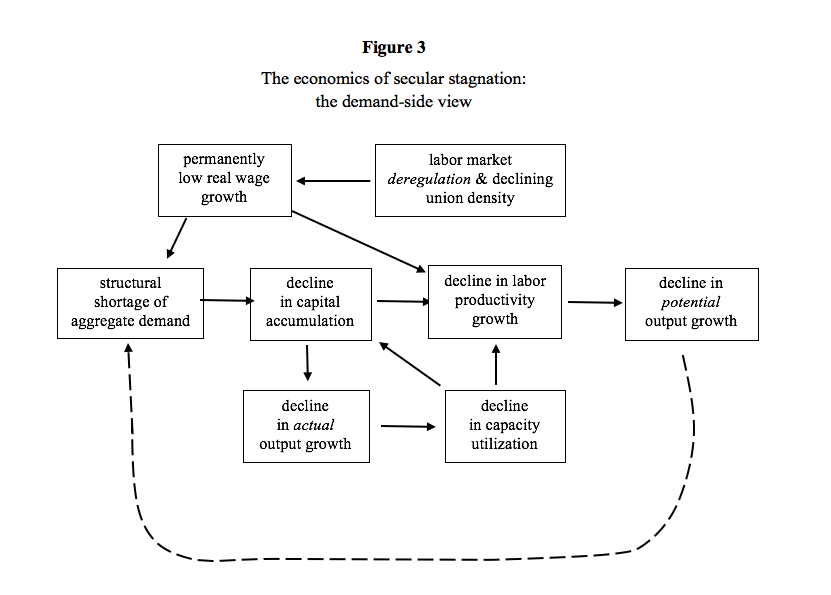

Demand matters in the long run, because business investment is overwhelmingly influenced by not by interest rates, but by ‘accelerator effects’ operating through aggregate demand (Kopp et al. 2019). Business investment, in turn, is the key determinant of labor productivity growth, innovation and technical progress. Accordingly, a structural decline in demand growth does depress labor productivity growth — through dithering business investment and a decline in capital deepening (Storm and Naastepad 2012). As a result, the growth rate of potential output must be low — this causal chain is illustrated in Figure 3. Crucially, once demand deficiency has lowered potential output growth, this means a low “speed limit” for actual growth, as inflation-adverse monetary policymakers, convinced that low TFP growth is due to a technological malaise, will keep actual growth close to sluggish potential growth — as happened in the U.S. (see Figure 1). In Figure 3, this feedback effect is illustrated by the dashed arrow from ‘potential output growth’ to a ‘structural shortage of aggregate demand’: because the ‘observed’ output gap is small (which makes the risk of inflation look large), monetary policy authorities will step on the brakes and raise interest rates in response to a revival of actual growth — nipping the recovery in the bud and creating a ‘sick recovery’ which ‘dies in its infancy’. Stagnation, while being avoidable because potential growth can be raised by higher investment and demand, becomes a self-fulfilling process (Storm 2017 ; Storm 2019; Fontanari et al. 2019).

In addition to all this, productivity growth will slow down when real wage growth declines. The key mechanism is this: rising real wages provide an incentive for firms to invest in labor-saving machinery and productivity growth surges as a result; but when wage growth is low, businesses have little incentive to invest in the modernization of their capital stock and productivity growth falters (Foley and Michl 1999; Basu 2010; Storm and Naastepad 2012). This is illustrated in Figure 3 by the arrow from ‘permanently low real wage growth’ to ‘decline in labor productivity growth’. In the U.S., the secular decline in real wage growth is strongly associated with the post-1980 reorientation in macroeconomic policy, away from full employment and towards low and stable inflation, which paved the way for labor market deregulation, a scaling down of social protection, a lowering of the reservation wage of workers, and a general weakening of the wage bargaining power of unions (Storm and Naastepad 2012). The recent rise in persons ‘working in alternative work arrangements’ or the ‘gig economy’ is merely the culmination of this earlier trend.

Conclusions

No single chart or empirical test can “prove” the case that secular stagnation is due to demand deficiency. Rather the case rests on a historical analysis of multiple pieces of evidence, which (as I argue for the U.S.) all point in the same direction: the slowdown in productivity growth reflects a demand (management) crisis, with the ‘under-consumption’ driven by stagnating real wages, rising inequality and greater job insecurity and polarization. Demand is leading supply, in the short as well as in the long run. The important dynamic macro channels through which demand growth influences productivity growth and hence potential output growth, all listed in Figure 3, deserve more attention in research.

Recognizing the importance of demand growth to long-run growth has profound and upsetting consequences for macro policy-making. Indeed, the all-too-neat separation between a ‘Keynesian’ short run and ‘supply-determined’ potential growth in the long run breaks down — and so do standard notions and measurements of ‘potential’ output growth and ‘output gaps’ (Fontanari et al. 2019). What must be recognized is that structurally weak demand growth forces down potential growth, whereas faster demand growth, supported by more expansionary, full-employment oriented fiscal and monetary policies, raises productivity growth and potential output. Conventional (supply-side) measures of potential output which ignore the dynamic demand-side channels, systematically overemphasize the ‘inflation barrier’ and methodically underestimate the margins for expansion of actual output (Fontanari et al. 2019) and thereby legitimate a structural deflationary bias in macro policy (Storm and Naastepad 2012; Girardi et al. 2018; Storm 2017; Storm 2019). What is not recognized, at great cost to society, is that higher demand may gradually remove the scarcities and bottlenecks which in the short run might create inflation pressures.

Stagnation is a sad instance of iatrogenesis: a pathology caused by the exact economist experts whose task it is to improve the economy’s health. To fail better, we must try again and discard ‘decided opinion’ that secular stagnation is an exclusively supply-side phenomenon and recognize that demand drives growth ‘all the way’ (see also Taylor et al. 2019). Without new economic thinking, macro policy will retain its deflationary biases and secular stagnation remains the ‘normal’.

See original post for references

I kept looking for some acknowledgement that, confronted with a plethora of global limits (Climate change, resource depletion, population growth…), economic growth is no longer possible. The author is looking at historical models that have little or no relevance to today’s situation. …the proverbial “elephant in the room.”

Yes, this is sorely lacking.

If economic growth results in digging the climate change hole ever deeper, perhaps the assumed “measured economic growth is always positive for the world” aspect is quite wrong.

If measured labor productivity is increased due to the higher consumption of hydrocarbons, then the world could be better off with lower labor productivity, as more human labor is substituted for burned hydrocarbon energy providing net incremental CO2 production is lower.

This appears to be an amazing oversight, where damage to the living world from economic growth is not counted in the GDP numbers.

And we have economist Tyler Cowen pushing for population growth while acknowledging a warming world.

“Don’t feel guilty about bringing children into a warming world. Be hopeful that they can help solve the problem.”

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-03-14/want-to-help-fight-climate-change-have-more-children

Strawman. Who is arguing “measured economic growth is always positive for the world”?

The debate Storm is taking on is whether policy should be geared toward demand expansion through full employment vs. Summers et al. who, to the delight of their sponsors, throw up their hands at generalised slow growth and place the blame on demographics and other forces outside the purview of policy.

The problem with the argument that we should not be focusing on growth is that the secular stagnation is nowhere near homogeneous across wealth levels. The extremely wealthy–who consume a far higher per capita proportion of the scarce resources you point to–are not experiencing any slowdown in GDP; they’re growing like kudzu. The bottom 90%, not so much.

There are other valid questions to be raised: is GDP accurate for measuring economic growth? (spoiler: no). Will the current economic model make the planet uninhabitable? (spoiler: yes), etc. But, as can be seen from how increasing inequality and applying austerity have not ameliorated resource depletion and climate change, those questions are not incident to the debate Storm is addressing.

re: Strawman. Who is arguing “measured economic growth is always positive for the world”?

Perhaps I am in error in observing that politicians (and the MSM) point to increasing a country’s GDP as a “good thing” and decreasing a country’s GDP as a “bad thing”.

In fact, the article itself has “This, in turn, is argued to have lowered the growth rates of both potential and actual GDP.”, suggesting that increasing GDP is a good goal.

Joseph Stiglitz has argued that GDP is a bad measure of well-being.

https://www.socialeurope.eu/beyond-gdp

That GDP does not capture well-being for the population and planet seems seldom addressed in the MSM.

Perhaps the way to slow the pace of making the planet uninhabitable is to advocate “austerity for all” that also applies to the wealthy?

This could take the form of taxes on wealthy real estate developments, limiting air travel and tourism and taxes on luxury goods.

If the resource depletion attributed to the wealthy is simply moved to lower income groups, than the severe effects of climate change could manifest at the same time frame.

Thank you.

Perpetual growth is not physically possible nor desirable.

Growth as a consequence of monetary inflation is false and distorts the signals of how we steward this process.

There is ample opportunity to restructure an economy in a thoughtful and proper manner, including compassion, and not end up with the sole metric or measuring stick of “growth in all things” including various measures of income or wages, GDP and so on.

We need to re-think which tool or measuring stick we use to guide us in stewardship. Stewardship does require action and often requires a bit of change personally and in the aggregate.

Correct me if I’m misunderstanding you. Your point is: since there are these imminent global limits, Storm’s policy recommendations (fiscal expansion, full employment) are invalid.

The clear logical consequence then is that the status quo is better than Storm’s proposals, because allowing the bottom 90% of the planet a greater proportion of the disappearing pie would make the pie vanish even faster.

For those of us in the third world, please ‘splain how that does not translate into a giant “FYIGM”.

Doesn’t anyone remember that Henry Ford created explosive growth in his company by paying workers more so they could buy his cars?(Of course he didn’t like it when workers joined unions in reaction to slave-holder tactics.)

He paid his workers more because he worked them sufficiently harder than his competitors that he could not retain them without paying a significant premium.

And if you look at who was actually purchasing automobiles in the teens and twenties, the demographic was not people making what his workers got.

And that’s before we get to 1929.

My reaction to this post?

Well, DUH! The economists finally caught up with the rest of us.

Moderator, please.

Almost all of the links in the post are blank and there are a bunch of references to other papers that aren’t links at all.

Perhaps a bit of editing is called for. ;)

I’ll also take this opportunity to thank the moderators for their excellent work.

That’s how the original article is at INET.

A lot of things like

[a href=”about:blank”]Storm 2019[/a]

(brackets modified, of course.)

The weird thing is that I can’t find this article through INET’s own home page. Neither by just looking, nor by searching on the author, nor by searching on the title.

Click on the link at the bottom of the post above that says “see original post for references”

I think there’s also room for an argument from Animal Spirits, as Keynes coined the term. Once top business leaders look around them and see they have everything they need the way things are, they see no reason to work harder (or, have their people work harder) and produce more. What would change for them?

You have highlighted the Vegetable Spirits corollary, the Potted Plants of that perfect market.

So there is simply no option to a consumer based economy?

How do we get people to drive less, fly less, buy less, waste less, while at the same time increase demand across the board? Seems to me to be a question so idiotic that doesn’t even deserve to be asked. But then again I’m not an economist.

I strongly believe the Amish are onto something.

I think in the same way everyone was encouraged to want more. They spoon feed us these ideas from when we can think, so maybe we ought to be teaching ourselves better values from a young age

Fig. 3 looks right to me.

30 years of flat wages, increased housing/medical/education costs, rising household debt loads, these must put downward pressure on disposable income and discretionary purchases, aka demand.

One example: Enrollments in 4 year colleges have been falling since 2012. New student loans are also falling. The most amazing nonsense is giving for this fall off. One particular “reason” cited is the drop in births between 2008 and 2012. Pretty sure 7 to 12 year-olds don’t attend college. No mention of household debt loads and colleges’ ever rising costs. Shorter: The fall in demand for college enrollment is not caused by a savings glut.

In California the university system is so overpopulated that students who qualify (state standards) are turned

away. Some go to community college and then try again. My local community college has 15k students (only 8k full-time) and it appears school/work arrangements predominate. Many decide that working full-time is their best option, right now. I think many are recognizing the debt load of a 4-year degree isn’t a good idea.

My boss told me prior to the GFC, that a friend of his, a hedge fund guy told him we were about to experience “the biggest transfer of wealth in history“, and so it happened, We the People were ripped off for $trillions.

I recently asked my boss what his friend was saying about our current situation.

He got sort of testy with me, and blurted out that there was “…more money that ever…” and I got the impression he was implying that all We the People had to do was start spending all that money.

At first I thought he mistook all the money that he and his peers have, as an indication that everyone was in the same shape, but now I realize that what he was wishfully thinking was that consumers should turn the newly ‘created‘ equity in their homes into a rerun of the lead-up to the GFC.

Ain’t gonna happen.

It seems to me a clear indicator, if one was needed, that the 1% hasn’t learned a thing about how the rest of us reacted to the GFC, they expect us to once again voluntarily walk the plank of debt fueled consumption.

The lack of consumer demand is their fault, not ours, and our reluctance to transfer our supposed, and mostly illusory wealth into their pockets is a totally natural reaction, and a clear indication that at least We the People learned something from experience that went right over the heads of Professional Managerial Class.

In reaction to his peevish reaction to my inquiry, I told my boss that considering we had had this sort of conversation only twice in 13 years, I didn’t consider it an unreasonable question, or topic.

Thanks for an enlightening comment. Seems it was premeditated down to the anticipated derivative effects and monetary policy prescriptions that enabled transfer of assets from defaulting and financially distressed debtors into “strong hands”, followed by the subsequent ramp of asset prices. As Balzac’s observed: “Behind every great fortune lies a great crime.” But as you pointed out, it does require participation of the marks; whether as a result of financial repression, greed or naïveté.

I can understand how a wide breadth wage increase would increase demand but wouldn’t that diminish profits which would diminish investment. What benefit is there in selling more if you’re not making a profit. The only mechanism that I see is for some entrepreneur to introduce competition using more productive technology to maintain profits. This worked for Ford because he created a market for a new product that few people owned. If McDonalds increases wages and decides to automate I doubt that they will increase the market for hamburgers. The result will be fewer workers making burgers.

>What benefit is there in selling more if you’re not making a profit.

I dunno, ask Jeff Bezos.

>to introduce competition using more productive technology to maintain profits. This worked for Ford because he created a market for a new product

Huh? Did he become more competitive in “the market” or did he create a new market? Methinks you need to rethink this.

> I doubt that they will increase the market for hamburgers.

The market for hamburgers dumped out of a window into a car of a harried person/family does not depend very much on the price or how they are produced. It more depends on the concentration of harried families with low taste and a moderate budget and how that intersects with the location of said window.

Yes, Bezos is a perfect example. He used technology/capital to replace retail workers and store owners. I don’t know the net loss of jobs number in retail but I’m sure it’s substantial. Of course Amazon did not happen because retail workers were getting big pay raises. Actually, I’m forgetting what issue we ‘re arguing.

OK, higher pay for retail workers might have helped Amazon to happen faster but I agree it would have happened anyway. I would also agree that higher pay for Amazon workers would/will increase demand since Amazon dominates retail and consumption is what we do.

This line of thinking doesn’t hold because wages are a fraction of the total cost of firms. If wages are 20% of the cost of sales and you sell at a 100% markup over cost, you can make up a 100% increase in wages with only a 30% increase in sales. That’s in dollar for dollar terms, obviously your margin % would shrink slightly. (from 50% to 33% in this example).

Applied universally, if everyone’s wage doubled don’t you think demand might pick up by more than 30%? Obviously this is an extreme example meant to highly the numbers. If wages go up 25% you only need to see a 7% increase in sales.

If a job can be automated, it will be eventually. Higher wages might convince McDonald’s to automate earlier, but they still would eventually even at lower wages. They just have to wait for the cost of the technology to come down. Therefore I don’t see an argument for keeping wages low to prevent automation.

These economists are like the pagan priesthood of Rome, prophecying future greatness for Rome based on the growth of empire in the past, excusing all manner of pathologies of Roman elite, assuring faith in the empire even unto it’s collapse.

Christians overcame the empire, and ruled for 1500 years. Supplanted by secular science, the vast majority of economists today exist to bolster faith in and subservience to empire and it’s elite.

What will supplant secular science, in the collapse of secular economic empire?

This borders on superficial. I don’t like Larry’s analysis of anything, but all I see here is a too-fine line between potential growth and potential saturation. We need demand but what kind of demand? Maybe controlled demand for all I know. What is emerging is a command economy. There are too many critical variables to not take them all into account. I think the recent post on the efficient use of resources to create viable economies is more to the point than Storm’s discussion of unspecified “demand” because that insinuates supply side investment into the economy to stimulate growth which is our nemesis right now. There’s no question our economies are out of balance. But to try to balance inequalities by raising wages by stimulating unnecessary demand is wheel spinning. If we were to become more “productive” by smarter and more efficient use of resources, thereby stabilizing economies it would be a better long term trajectory of creative productivity. Iatrogenesis is the opposite of evolution and I don’t see much evolution in this post.

In my opinion this article, like most topical Post-Keynesian analyses I’ve seen, ignores several key factors. One that has already been mentioned in another comment is the reality of climate change, pollution, and resource depletion putting a hard cap on growth sooner rather than later. Another that has already been mentioned is profit: capitalists invest when there is an opportunity for profit. This is related to demand obviously, but Post-Keynesians seem to ignore it in favor of demand.

Finally, and most fundamentally, I deeply disagree with the theory and its conclusions on a somewhat philosophical ground. The author claims that a rogue group of elite economists have hijacked the economy and led us down a pathway to stagnation. The remedy is to kick out the sophists and put new, smarter people in charge of the economy. This, it seems to me, ignores the reality of capitalist institutions: the belief systems and institutions are guided primarily by the needs of the powerful (capitalists and their allies), not the other way around (although I will concede that feedback is probable). Within this framework, the ideology of the elite economists matters rather less than the material interests of the powerful, and the powerful will attempt to make sure that the dominant ideology is compatible with maximizing their power. The problem is not simply that we have the wrong economists and ideologues in power; the system itself generates the problems as a natural outcome of the basic relations of society and it reinforces ideologies that reinforce itself. Therefore, the solution to this problem cannot be replacing the economic and administrative elites within existing institutions: those institutions are part of the problem to begin with. We must instead seek to replace and supersede the institutions with ones that 1) better respond to our needs, and 2) are stable and self reinforcing.

Two quick notes:

1) My explanation beats the author’s on the grounds of simplicity and materialism.

2) My explanation is pretty basic Marxist materialism with a tinge of philosophical systems theory, for those curious as to where these ideas came from.

Yes.

Economics is not science (witness its failure to predict much of anything); it’s political ideology decorated and disguised with mathematics. (Obviously, some economists are better than others – but that might be because we agree with them.)

In my experience, most economists are far more interested in the noun rather than the verb.

You cannot swing your arm without hitting a(n) {insert modern activity here} economist.

They can be quite astute observers of the way things are within their own realm/specialty but they always pull up the shutters on the basic stuff.

But that is just my experience.

(though i did feel a twinge of recognition when the late chalmers johnson descibed it as the most imperialist profession)

I agree with much of your analysis, however there is much the author gets right;

OTOH, he does rather badly miss on the issue of where to place the blame;

I believe that most NC readers see clearly the fault lies with those who employ the ‘economist experts’ as tools to further their interests, it is clear, they do not see their task as improving the economy’s health, but rather, making themselves rich.

IOW, Paul Krugman, and the rest of the supposed ‘economic experts’ do not inform Jamie Diamond’s economic outlook and decision making, they cheer-lead for those decisions because that’s their job.

I actually agree that he gets much right. I do think the Post-Keynesians understand the economy a lot better than the Neo-Classical and New-Keynesian ideologues and I regularly read their work (I’m a big Steve Keen fan for example). I think my major critique of the demand centered analysis is that ignores the role of profit in investment. I remain somewhat unconvinced that the slowdown in capitalist economies is primarily due to underconsumption and not to other factors like eg profit. I’ve read good Marxist critiques of underconsumption theory of crisis from Michael Roberts and Boffy as two examples.

I also think that Post-Keynesians are wrong to dispose so easily of value theory, especially the labor theory of value (which at the very least has not been soundly defeated as the mainstream claims and retains good empirical and historical agreement).

You wrote

No that is not Storm’s argument. He wrote textually

He is not proposing new economists, he is calling for a correction of incorrect economic theory, just as you are. Does Storm believe, as you do (and I do too) that “the reality of capitalist institutions: the belief systems and institutions are guided primarily by the needs of the powerful”? Perhaps, but is it necessary to make that explicit everytime one writes an article to rebuke an incorrect doctrine?

That aside, I would be interested to hear how Post-Keynesians ignore profit to favour demand. For example, one of Storm’s key points is

I.e., businesses invest where they think they can obtain profit, and to obtain profit, businesses need customers (demand). If customers don’t have money, the profit motive disappears. How does this framework “seem to ignore [profit] in favor of demand”?

What is the effect of executive salaries that have silently risen from 40% of average worker salary to 400% and sometimes 1000% over the last two decades? Capital is external to the multiple “chiefs”: executive officer, operating officer, financial officer, information officer and more. As directors of other corporations, they are also in place to approve salaries across the board, including the not-for-profits.

The balance sheet has used downsizing to make executive salary+bonus less noticeable, and the shifting of risk in medical benefits followed. All of this is part of “The Economy” but it does not show up in the analyses. It is significant that CEOs are bonused on the bottom line and not on real revenue.

“: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.””

Hmmm – it’s off-topic, but this applies to politics, too. There are many ways to put it, like “trying the same thing while expecting different results.”

It’s so obviously wrong that it reveals a hidden, maybe unconscious agenda.

” But the real problem is the alarming steady decline in total-factor-productivity (TFP) growth, the main component of potential output growth.”

The Law of Diminishing Returns. Also, evidence that computers do not in fact increase productivity overall, something I’ve seen claimed elsewhere. They certainly don’t increase mine. It’s a good question what they actually do.

There’s a frightening amount of econospeak in this article and that’s part of the problem. Most economists see the economy as a financial system when it is in fact an energy system as Tim Morgan has pointed out at https://surplusenergyeconomics.wordpress.com. Econ textbooks talk about the 3 factors of production as land, labor and capital. I think they would be better advised to use matter, energy and information instead as nothing can be produced without these 3 factors.

Morgan states that the economy runs on surplus energy and uses the term Energy Cost of Energy (ECoE) to quantify this, where ECoE is the inverse of EROEI. As we deplete our resources at an ever increasing rate, the ECoE keeps rising and so a greater percentage of energy is used simply to extract energy, leaving less to be used for producing goods and services. This is also true of the ores we extract like copper, iron, and tin, etc. The result is that we use more energy to extract the fossil fuels and ores that we need, leaving less for producing “stuff” we want, and leading to slower growth.

The only solution I see to this problem is to stop growing the economy. An economy based on the idea that we can consume more and more every year while throwing away anything that wears out and buying new stuff is not only contrary to the laws of physics but is frankly insane. Of course, this is a decidedly unpopular option, especially for TPTB. But in the end it is what we will be forced to do.

So for me the cause of “secular stagnation” is mainly resource depletion, made worse by population increase. In fact, it would probably be better to use the term “secular contraction” because that’s where we are inevitably heading. Since economists have been carefully trained to ignore the fact that the economy is part of the natural world and that there are these things called the Laws of Thermodynamics, I expect they’ll continue to treat the problem with econospeak mumbo jumbo about supply and demand as their vaunted economy slowly goes down the tubes. Hopefully the next generation of economists will have a bit more common sense.

+1000!

This lands for me. thank you for sharing.

What arises in me is how we worship at the altar of short term profits that maximize public risk and resource depletion to maximize private gain and personal or even “class” profit.

It seems environmental sustainability isn’t factored into the equation enough to drive any behaviour except avoidance of the issue. Profit uber alles.

I wonder at the moral decay that can occur when the what’s good (profitable) for an individual drives decision making without consideration for the greater good (sustainability).

To put it indelicately, aren’t we just shitting where we eat?

Certainly the long-term impoverishment of non-elite America by financialization, neoliberal rent-seeking, and outright looting (private equity) has been an important contributor to a slackening of demand. But that trend long predates the stagnation experienced since the 2008 debacle, and the global economy experienced robust growth in the years leading up to it. An alternative explanation, as advanced by Jeffrey Snider across many analytic essays, proceeds roughly as follows.

The shadowy Eurodollar system provides dollar-based credit creation by offshore branches of banks mostly outside the purview of domestic central banks and regulators. This entirely credit-based, almost completely unregulated system had been the true engine of globalization through the exhuberant creation of Eurodollars to fund international trade and investment.

In the 2008 crisis, the system broke down as banks were no longer willing to trust each other (nor accept ever-more dodgy collateral as a basis for lending). Without this firehose of ever-expanding credit creation, the system has drifted for more than a decade, suffering recurrent bouts of dollar shortage that manifest in stuttering growth and chronic near-reccession conditions. As such, the possibilities for growth in the global economy have been ratcheted downwards and stagnation is the new normal.

Regarding economic growth and finite resources, it’s well to consider the quality of economic growth. If growth is based on consumption of finite resources it’s naturally capped. But if it instead relies on sustainable production and the satisfaction of human needs with human services, it’s not clear that it has a natural bound, especially since it’s designated in fiat currency which itself has no natural bound. If we devote ourselves sincerely to the responsibility of society to the fulfilment of all of its citizen’s needs in a sustainable fashion, economic growth can probably be left take care of itself.

Fiat currencies?? Not useful. That just manages capital flows. You must change your thinking away from capitalism and usury.