For those of you who remember the multiple Greek bond restructurings, the gimmicks now being used to pretty up the prospects for student loans look awfully familiar.

One of the devices Greece’s creditors used to make it more plausible that broke and prostrated Greece might someday make good was extending maturities to lower the amount due in any year. This was particularly true of the loans that came from European governments, where payments in the 2015 restructuring were deferred to 2020 and 2022. We pointed out that the maturities of various borrowings had already been pushed out so far (40 to 60 years) that additional deferrals would buy little in the way of payment relief.

The Wall Street Journal tonight describes how a similar trick is being used with student loans. Unlike Greece, investors in bonds that have Federally-guaranteed student loans as the source of their cash flows will eventually get their money. However, as the article explains, the timing is in question. And unlike Greece’s creditors, who were more concerned about optics than discounted cash flows, bond investors know that payments that come in late are less valuable than ones that come in as scheduled.

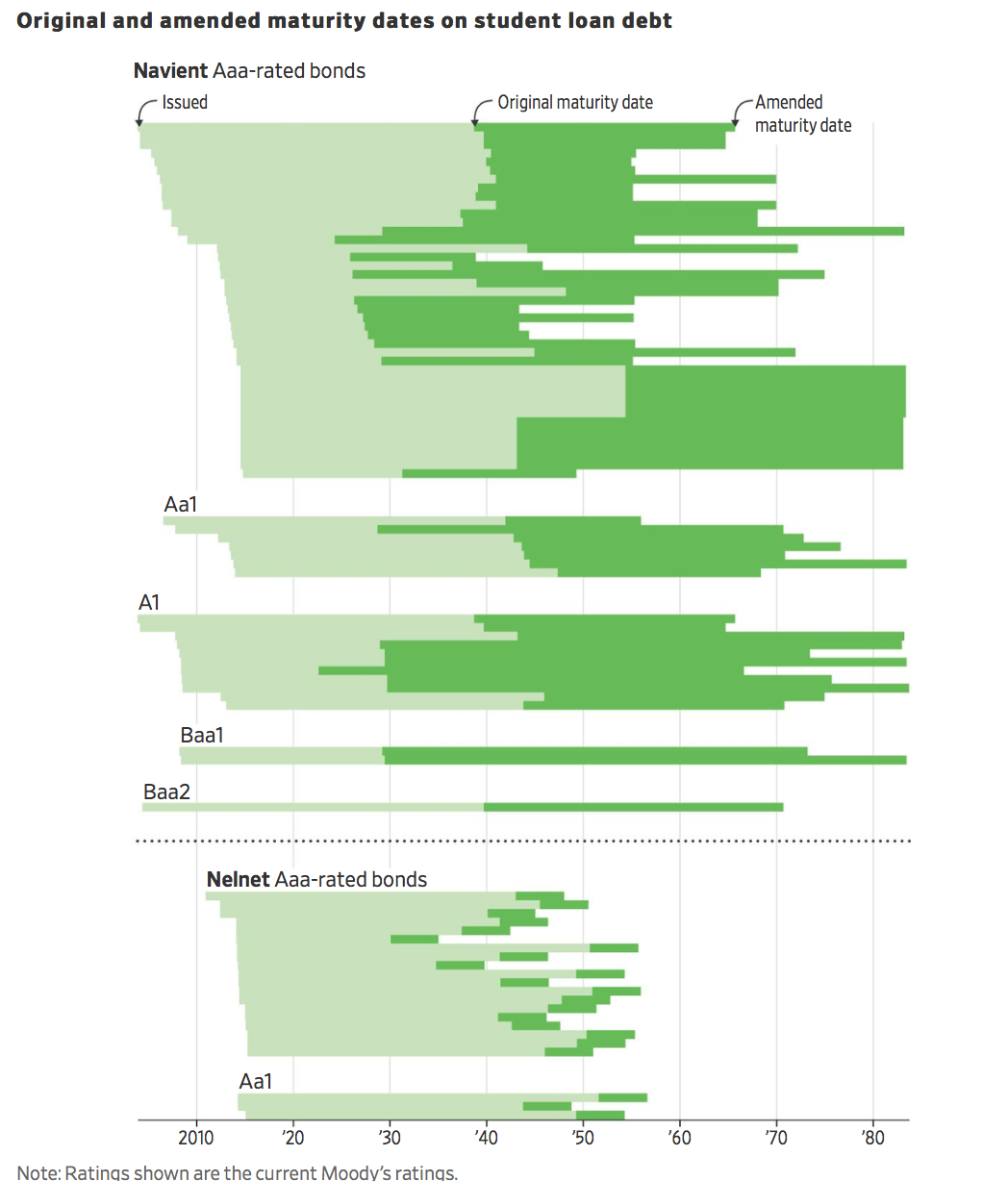

Bond rating agencies are playing along with this “kick the can” strategy, typically issuing a downgrade at the time the maturity is extended, then marking it back up to triple A. From the Journal:

Because borrowers were taking longer to pay off their loans, there was a risk the bonds backed by the loans wouldn’t be paid off in time. Bond-rating firms were watching and getting ready to downgrade the highly rated bonds, potentially causing losses for investors.

The issuer of the bonds and the investors who owned them hatched a plan to avoid the downgrades. Their solution: make sure bonds were paid off in time by extending their maturity dates by decades…

Bond-ratings firms like Moody’s Corp. and Fitch Ratings follow strict rules. They will downgrade a security if they don’t think it will pay off by the due date, even when the underlying loans are guaranteed by the federal government…

Investors who hold on will eventually get paid back, but a downgrade might cause them to suffer a temporary loss….

Some bonds went on a ratings roller-coaster ride, including a $406 million chunk of triple-A debt that Moody’s downgraded to junk on Nov. 1, 2016. Later that month, the maturity date was moved from 2026 to 2055. Within weeks, Moody’s upgraded the bond back up to triple-A.

Other bonds ended up with widely divergent ratings. A $30 million chunk of a 2008 student bond deal is either triple-A, if you believe Moody’s, or deep inside junk territory, if you believe Fitch. That bond is also now due in 2083.

Mind you, this payment delay issue applies only to a subset of student loans, ones that Congress allowed to participate in an income-based repayment scheme, which limits monthly payments to 15% of discretionary income. The program was short-lived, ending with loans from 2010, but still has $262 billion in principal outstanding, of which roughly 26% is in default. The later loans total $1.2 trillion, with about 10% in default.

The Journal points out that investors have incentives to maneuver borrowers into programs that aren’t in their best interest:

The threat of downgrades got the attention of federal regulators at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. In a 2015 report, the agency’s student loan ombudsman cited issuers’ “economic incentive to ensure that bonds backed by these loans perform on schedule” as a concern because it might mean issuers steer borrowers toward temporary payment pauses and away from income-based repayment plans that provide longer-term relief.

In January 2017, the CFPB sued [student loan servicer] Navient for allegedly “failing borrowers at every stage of repayment. ” Navient says the CFPB’s allegations are false and is fighting the lawsuit.

Needless to say, we see in a very small way how securitization increases rigidity in handling borrower distress. We saw it in a far more dramatic manner during the foreclosure crisis, when loan servicers refused to make modifications that would have both salvaged many borrowers and reduced losses to the securitization trust. The immediate reason was that they were paid to foreclose and not paid to modify loans, which is a high-touch, customized activity, as much work as underwriting a new loan. But an additional reason was so-called “tranche warfare”: the riskiest bond tranche that was still getting payouts benefitted from foreclosures, because they would still get advances from the servicer until the foreclosed home was sold, while if a loan was modified, their income would be hit immediately. Those investors were often hedge funds who’d picked up those bonds at distresses prices and were just the sort who would really could and would sue the servicers for arguably hurting their interest.

However the events above illustrate an interesting conundrum. What would happen if Elizabeth Warren’s awfully-slow-in-coming proposal to have student loans be dischargeable in bankruptcy were to become law again? You’d see a lot of broke borrowers doing just that, filing for bankruptcy to get their loans written off or reduced. There is other proposed Federal legislation to provide relief for student loans, including two with new income-based repayment plans with lower required payments (10% of discretionary income versus the old 15% level). So far, investors seem to recognize that government guaranteed student loans are such a gimmie that they aren’t about to squawk much publicly about having some features less favorable to them become more common. But rest assured, they have plenty of proxies they can use to argue their self-serving case.

I don’t understand how income-based repayment plans do anyone any favors. It certainly doesn’t help the borrower, except in the short term. In the long term, many borrowers are finding that their principal keeps going up despite years of payments. Hey dude—do you even know how loans work? If you aren’t paying at least the accrued interest, then you’re going deeper in debt. This ain’t rocket surgery.

“But, but, but….otherwise the borrowers can’t pay!” Then don’t lend them so much money, you dummy!

So, with federal originated loans, at the time the term ends, that principal is forgiven. Of course it counts as income (unless you are one of the lucky pslf winners), but that still may be a better deal for some. When my pslf plan fell through, and the 6 figure partner job didn’t appear, doing income based for my $180k in law school debt was the only way. Now that interest has capitalized 2 times due to forebearance periods of changing employment, then plan is even better. When the principal is due in 13 years, it is almost guaranteed I’ll be insolvent. I’ll definitely pay less than sticker price for my education in that case, which is still too much.

So maybe your assumptions are off?

Can’t you see how awful that is? You are stuck in insolvency with a huge undischargeable loan, and the principal is getting larger and larger. I’m guessing that it hampers your ability to buy a home and take risks in the practice of law, and the best-case scenario you seem to admit is that you will continue to be insolvent in 13 years, so the ginormous principal will be forgiven (if you are lucky) and you will only have to pay what?—20%, 25% of the forgiven principal in taxes?

I graduated law school in 1995 with $52,000 in debt—which may not be that far off from your situation, considering inflation and the interest rate I pay. This was before the shell game that is income-based payment schemes. My first job paid $36,000/yr and payments were $900 per month or so, so I had to consolidate. Unfortunately for me, this was 1996, and they locked in my rate at 9%*, so I’ve been paying $450/mo. for 25 years, and I have three payments left. Never been delinquent and have never been in deferral after consolidation.

At the end of the day, I’ll have paid over $125,000—$75,000 in interest!—for a $52,000 education.

* NINE FRIGGIN’ PERCENT for a FEDERALLY GUARANTEED DEBT OBLIGATION—can you believe it? And by law I am not allowed to refinance to lower my rate.

So I am personally familiar with the raping that is the student loan program. I don’t know why anyone would go to law school today. The top 15% will earn good money and the rest of the schmucks will plod along, stuck permanently in the professional/managerial class.

As a lawyer, does it ever occur to you that government privileges for private credit creation violate equal protection under the law in favor of the banks and the most so-called credit worthy, typically the richer, at the expense, one way or another*, of the poorer?

Ah, if we could only get the lawyers to fight the banks! Winning that battle could earn lawyers honor for centuries.

*.e.g. the automating away of jobs with the workers’ own legally stolen purchasing power/investment opportunity.

You presume that the courts don’t exist to protect the powers that be.

I do think it’s terrible. But better than if no ibr. Also, if I’m insolvent when the principal is forgiven, I’ll likely not have a tax liability. That’s the hope.

It makes the risk trade off more equitable. If the college degree doesn’t pay off for the students career prospects, ultimately Uncle Sam is on the hook for the loan balances.

Student loan debt is on an unsustainable path with ever more debt being foisted on fewer students on a year over year basis.

Yes, I know how the system works (see above), but reducing payments so that they are less than accumulating interest does not help the borrower in the long run, at least until he/she hits the forgiveness jackpot (if that day ever comes), and then they still have to pay taxes. (Shakes head.)

There are other ways it could be done—either pause the loan at 0% interest, or maintain the present amortization schedule, but forgive on a month-to-month basis the amount of the principal/interest that exceeds the “equitable” income-based loan payment amount. In either of those ways, the principal does not continue to grow, and the borrowers “hole” does not get deeper and deeper.

If the true limit to fiat creation is politically acceptable price inflation, then let’s take note that de-privileging the banks would be deflationary by itself* and thus allow a larger equal Citizen’s Dividend during the de-privileging period.

And, of course, a Citizen’s Dividend could be used to pay down private debt.

It’s rather beautiful how reform allows restitution and vice-versa, yes?

*Because banks would be unable to safely create new deposits at a rate to compensate for the repayment of existing bank loans.

And this is why I’m knocking on doors for Bernie in Iowa. Forgive student loan debt, forgive medical debt, wipe the slate clean. On Bernie’s website it says cancel “all” student loan debt and I don’t see any exclusion for graduate school. It also says the interest rate on future loans will be capped at 1.88%.

I’m a big supporter of Bernie, but I think it prudent to fix high ed funding going forward before we eliminate existing debt. Otherwise, we’re going to be right back in the same problem.

They must somehow address financing for public universities vs. financing for private universities. I don’t have any suggestions at this point.

Solution is easy — revert bankruptcy law to pre-Biden era, where *all* debt is dischargable.

Lenders will refuse to hand out college money, and colleges will be forced to drop their prices back to an affordable level.

Then don’t lend them so much money, you dummy! Bill Carson

What money? Our economy runs on private bank deposits, not on fiat itself, and banks create those too* when they “lend.”

And, due to government privilege, private banks can “safely” create vastly more deposits than they otherwise could and thereby drive the population into debt with them.

We could have an honest system with the honest lending of existing fiat (and whatever deposits entirely private banks with entirely voluntary depositors might create) and a Citizen’s Dividend and other ethical measures to keep interest rates low. The question then is what excuse is there for continuing with the current inherently corrupt system?

*The other sources of private bank deposits are fiat creation via deficit spending for the general welfare (at least purportedly ) and fiat creation by the Central Bank for the private welfare of banks and asset owners.

I understand how banks create the money out of thin air, and the unfairness of throwing the borrowers into virtual indentured servitude over a semi-fictional indebtedness. I am all for doing away with the present system.

> Bond-ratings firms like Moody’s Corp. and Fitch Ratings follow strict rules . . .

It all depends on the definition of, strict and rules

The only strict rule is there are no rules. Look for the fine print in the paperwork obliging your children to make the bond owners whole.

Could this be one of the reasons why many students will need over 100 years to pay off their college debt?

Perhaps there might be a way to pass the student loan debts on to their children?

Warren’s bankruptcy plan. Credit Slips endorsement.

Yes, but why did Warren, Americas’ pre-eminent bankruptcy scholar, not propose this the minute after she was sworn in as Senator? Awfully convenient to take it up now when her campaign is fizzling. She can then bogusly claim Americans aren’t behind it.

Here’s a thought: Make the universities lend their endowments to their students.

It would be a good test of the universities’ confidence in the economic value of their product, and perhaps make them more selective about who they enrol.

There could be some adverse selection when the universities [with their superior knowledge of the applicant pool] skim off the candidates most likely to repay them, leaving the other lenders to deal with a picked-over pool of loan seekers.

Universities should definitely be disgorged of their endowments, and they should be used to lower tuition.