Yves here. This study supports our hypothesis that CalPERS’ Marcie Frost, who has managed to greatly increase her compensation since she joined the public pension fund, is overpaid. In general, in public pension funds, CEOs engage in administrative oversight and politicking, neither of which have much impact on performance.

I wonder if these findings can also be generalized to US not-for-profit hospital systems, which have been invaded, locust-like, by MBAs who seem much better at personal rent extraction than service delivery.

By Katharina Janke, Lecturer in Health Economics Modelling, Lancaster University; Carol Propper, Professor of Economics of Public Policy, CMPO, University of Bristol; Professor of Economics, TBS, Imperial College and CEPR Research Fellow; and Raffaella Sadun Thomas S. Murphy Associate Professor of Business Administration in the Strategy Unit at Harvard Business School. Originally published at VoxEU

Studies have shown that in the private sector, top managers and CEOs can make a difference in the performance of their organisations and have a ‘style’ that is portable across firms. This column uses the setting of hospitals in the English National Health Service to examine whether CEOs can make a difference in large and complex public sector organisations. The findings suggest that the CEOs of large public hospitals do not have a significant impact on performance, casting doubt on the ‘turnaround CEO’ approach to management in the public sector.

Governments seeking to improve productivity in public services frequently turn to the private market for inspiration. A popular reform model is to give CEOs greater autonomy to run their organisations, accompanied by manager-specific compensation policies, performance-related pay, tighter monitoring, and dismissals (Besley and Ghatak 2003, Le Grand 2003). Such policies have been advocated internationally by organisations such as the World Bank and the OECD and have been implemented in countries across the globe.

These ideas build on findings that in the private sector, top managers and CEOs can make a difference in the performance of their organisations, and that CEOs have a ‘style’ that is portable across firms (Bertrand and Schoar 2003). Devolving decision making to the top managers of small organisations that provide public services – such as schools and development projects, or public-service organisations with simple tasks – has been shown to improve outcomes for service recipients (Bohlmark et al. 2016, Bloom et al. 2016, Fenizia 2019). But the effect of top managers on large and complex public sector organisations has hardly been examined. Can CEOs make a difference in this context?

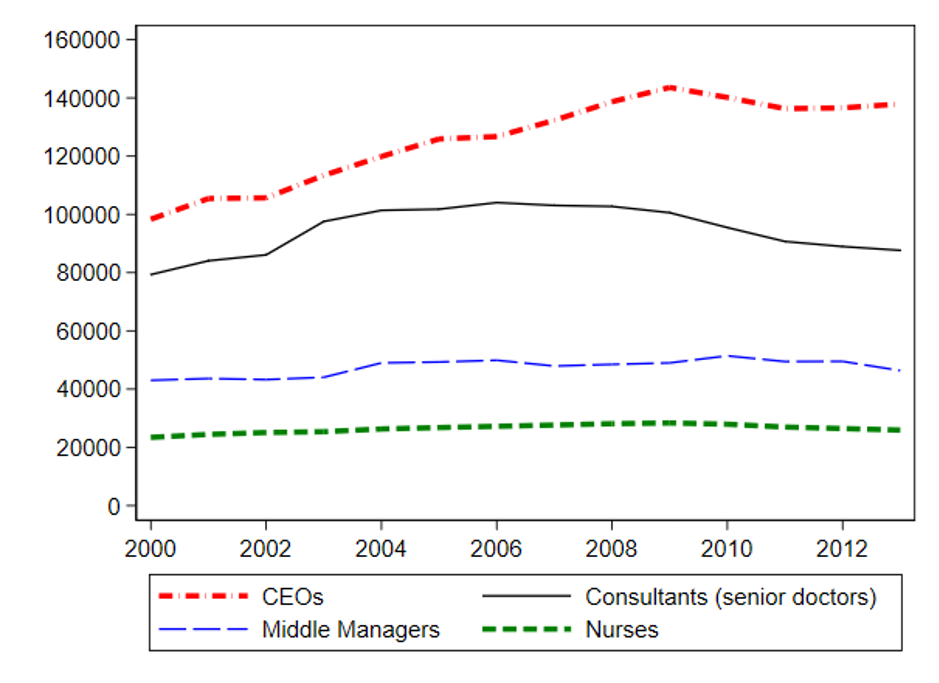

To answer this question, we examined the impact made by the CEOs of large and complex organisations operating in the public sector – specifically, in public hospitals in the English National Health Service (NHS) (Janke et al. 2019). The NHS is the fifth largest employer in the world, with approximately 1.2 million employees. NHS hospitals maintain an average of 4,500 employees, multi-million turnovers, and labour costs accounting for around 70% of the costs of production. NHS CEOs are well paid compared to other top managers in UK public service organisations. As we show in Figure 1, they are also well paid relative to NHS doctors and nurses, a fact that has led to press headlines decrying the pay of ‘fat cat’ bureaucrats in the NHS.

Figure 1 Mean annual pay of NHS staff by job type (CPI adjusted)

NHS hospitals provide an ideal setting in which to examine whether managers have a style that can be taken across organisations to bring about change, creating policies that give greater autonomy to managers who effectively improve productivity. In the late 1980s, the English government embarked on a large reform programme that replaced an administrative approach to hospital management with a highly decentralised model in which CEOs were given responsibility for the management and performance of individual public hospitals, and hospital boards could select and reward individual CEOs autonomously. Meanwhile, frequent moves by the same CEOs across different but comparable NHS hospitals make it possible to separate the role of manager-specific discretion for hospital performance from other persistent differences in hospital characteristics. Finally, government-published data on NHS hospitals cover inputs, throughputs, and outputs – both financial and clinical – and require hospitals to publish the pay awarded to their top managers. This allows us to complement the analysis of CEO performance with an examination of their compensation, and compare perceived differences in managerial ability (as proxied by their compensation) to actual differences (from our analysis of objective production measures).

We find considerable and persistent differences in CEO pay across NHS hospitals. These differences persist as CEOs move between hospitals and suggest that the independent NHS hospital boards, which hire CEOs and set their remuneration, perceive some to be better than others. Does this perception reflect actual differences in performance?

We find the answer is basically ‘no’: there is little consistent evidence that CEOs generate persistent performance effects across the organisations they lead. Put another way, we find that a CEO who has improved financial performance, decreased waiting lists, or improved clinical performance in one hospital cannot simply replicate this effect in the next.

We examine a number of possible reasons for this apparent lack of CEO effects in hospital production, which stands in contrast with the substantial and persistent differences in pay. First, we examine whether the lack of persistence across hospitals in production is driven by the assignment of good CEOs to poorly performing hospitals, or hospitals that have structural features that negatively affect the possibility of achieving good results. If this were the case, differences in pay across CEOs would not necessarily be mirrored by differences in hospital performance, since the best CEOs would be assigned to harder-to-change organisations. Second, we examine whether the lack of persistent CEO effects could be driven by the fact that mobile CEOs in the NHS tend to have short tenures (the average CEO is in one post for less than four years). In this case, CEOs might in fact differ in terms of their potential effect on hospital performance, but the effects could fail to materialise over short time horizons. Finally, we examine whether evidence exists of CEO-hospital match effects – i.e. whether specific types of CEOs perform better in specific types of hospitals, which would imply that CEOs matter, but only when there is a good fit between manager and hospital.

We find little evidence of endogenous assignment: a good performance is not followed by a bad one because the CEO moved to a difficult-to-manage hospital. But we do find some evidence of tenure effects: those CEOs who stay for a longer-than-average tenure seem to have more success generating change. This finding – combined with the evidence of substantial and persistent pay differentials – suggests that employers may overestimate the ability of CEOs to effect change over short periods. We do find some evidence that certain types of CEOs perform better in certain types of hospitals: those who are medically trained deliver higher clinical quality when running teaching hospitals, whilst those with a private sector background turn in a stronger financial performance when placed in hospitals which face more competition. But these effects do not persist when the CEOs move to another type of hospital, again suggesting that employers may overestimate the ability of CEOs to bring about change regardless of the circumstances they face.

Overall, we find that the CEOs of large public hospitals do not necessarily impact hospital performance, a result that contrasts sharply with earlier findings relating to the private sector and to smaller public sector organisations. Various structural factors may account for this lack of effect, including the public sector nature of the NHS, which may have inclined the effort of NHS CEOs towards the pursuit of political targets rather than performance-enhancing policies. The lack of a CEO effect may also be due, more broadly, to the complexity of hospital production, which transcends the fact that the NHS is publicly owned. From either perspective, our results cast doubt on the effectiveness of a ‘turnaround CEO’ approach – the model in which top managers frequently rotate across hospitals in pursuit of performance improvements – for large and complex public sector organisations.

See original post for references

I find this statement rather puzzling:

“…[CEOs] with a private sector background turn in a stronger financial performance when placed in hospitals which face more competition”

Competition??? Is there really some sort of competition facing NHS hospitals?

In related health care crapification news, the Chief Marketing Officer of Starbucks has joined the Board of Directors of Kaiser Foundation Health Plan/Hospitals. (I wish I were making this up…)

It would be interesting see a similar study of public sector university administrations. With the corporatization of higher education in recent decades, we’ve seen the same kinds of CEOs metastasizing throughout these institutions, bringing with them similar personality traits (psychopathy) and career paths (serial job hopping as they fail upwards).

Yours Truly has worked at a couple of public sector universities.

I would LOVE to provide information for this study. Oh, would I ever. Especially about the psychopathy and serial job hopping while failing upwards.

I agree. Might it be possible that CEO’s do not have much of a positive effect if the service or product is pretty stable, such as in education or health? One could go further and state that stable areas are stable because things have been pretty much optimized already. So trying to introduce supposed “advances” will likely backfire unless a manager knows the product/service extremely well. I mean business people have been using the same playbook for decades so the bag of tricks have probably been tried already. If you create a commodity, consistency of service/product would become much more important I think. Yet is that valued? Anyways, interesting article.

I don’t need a study to know that the administrators in the community college system for which I recent retired (Ontario colleges) are ineffectual – with the college presidents in particular being a waste of money. I can easily trade CEOs for Ontario college presidents in this sentence from Yves’ intro: “CEOs engage in administrative oversight and politicking, neither of which have much impact on performance.” The business-ification of academia and most non-profits has been ongoing for some in our neoliberal world. The bean counters are running amok and the higher level college administration positions I.e President, VP, Dean and Directors have become seen as good government jobs, given to people who know nothing about education or pedagogy. I am very happy to have recently retired and am now able to only Have to see it from afar instead of suffering within the system.

If CEO performance improves by paying them more I would conclude the wrong sort of people are being selected as CEOs. It is a great honor and privilege to call the shots in any organization. How much other compensation is really needed to attract talent? [Of course great care should be taken to filter out those who receive too much ‘compensation’ through their ability to control and direct the actions of others.] For many years until the discovery of Neoliberal Markets, Corporations were run reasonably well by very well compensated CEOs — a decimal point and some single digit multiplier better paid than rank and file. CEOs are just managers — not entrepreneurs [and entrepreneurs are allowed to keep entirely too much].

The scary part of CEOs in hospital management comes from determining how to measure their success. Neoliberal economics offers “stronger financial performance” which I would translate as maximizing profits — or for ‘non-profits’ — bang-per-buck derived through proxy measure(s). Hospitals are not supposed to deliver “stronger financial performance” — they are supposed to deliver medical care.

Interesting to see that the surge of the snake at the top of the graph largely coincides with Blair’s tenure. An age of ” Targets ” for public services which appear to have required the employment of the likes of whoever it was at the NHS, who came up with the nifty ruse of taking the wheels off the trolleys stacked with patients in corridors & classifying them as beds in order to fiddle the waiting lists for the real thing.

Adam Curtis covers the above & much besides in his 3 – part docu series ” The Trap “, some of which rang bells with my own experience as a young trainee manager in charge of production control for 3 small mineral plants, which were part of a much larger entity. One thing I did notice was the obsession with direct labour costs whereas the ever growing overhead fueled largely by constantly growing management costs was always ignored. The Works manager would be yet again urged to crack the whip as I sat there trying to appear something other than unconscious throughout yet another boring & IMO pointless meeting.

Later on as a freelancer I had dealings with a relatively large & world famous company who got big into marketing. They employed some tit from a then company called ” Tie Rack ” ( they did not manufacture ties ) & novelty supplanted quality, while they plastered ” Investors in People ” all over the place while sending virtually all of the production to the Far East. This eventually did not go down well & sales plummeted when it became public knowledge, not helped by the fact that the quality had also slipped significantly.

The majority of a once large industry went the same way with many companies going bust with the exception being those who followed the advice a TV troubleshooter, named Sir John Harvey-Jones formerly of ICI before Thatcher carved it up. He focused on Quality of product & design as did it seems the Germans whose once much smaller matching industry now dwarfs it’s British counterpart with a thriving export industry to the Far East.

And don’t forget the increase in mid-level paper pushers in the NHS (and I imagine in the US healthcare trainwreck), who can’t positively impact anything, but have tremendous power to deny, reject and refuse.

A trend I like to call “adminisflation.”

We have two types of people in the world – those with wealth and those hoping to acquire it. The latter have persuaded universities to offer courses in wealth accumulation as something progressive and it is these graduates who are infecting every human activity with their philosophy whether its business or art or humanitarian. Its the nature of our financial and economic systems that we follow the man with the money.

Competing ideologies – think Corbyn, China, Islam – have to fall so we can progress.

There are more than two types of people in the world. I believe you are very wrong. There are people with wealth and there are those who like me would like to just live life without worry about becoming homeless; live a life without worry that I cannot provide for my children; just live a life without worry that my children cannot get by and perhaps do better than I did; just live a life without worry I could be ruined by a medical emergency or medical problem. I am also worried that the world I leave to my children is a world which will try them in horrific ways I cannot imagine or foresee.

Did you drink too much of the KoolAid or are you as troubled by the direction of our world as I am?

Corbyn, China, Islam have to fall so we can progress? I don’t know about Corbyn — I’m a Yank so Corbyn isn’t my problem. and China and Islam brought us much of the progress we presently enjoy — so why should I root for their fall?

I think he is correct in that they have to fall as they are competition to that which has held up the West since about the time that Shrewsbury gangster, glorified as Clive of India took control of the subcontinent. Resources are getting much harder to extract due to depletion & growing competition from the East. As for Corbyn he would be a threat to extraction in another way.

I suspect perhaps incorrectly that RB like myself sees it as just a fact of life for those who are running or ruining things, rather than something that we both desire.

Perhaps it’s part of a cycle – In Elizabethan England when the East India Company first reared it’s ugly head, the countries world GDP share was 2% as opposed to the Mughal empires which was 42%. It might be remembered as an era whose beginning & end was roughly marked by 2 queens of the same name.

CEOs get paid more because they are inherently more valuable than say, you or I!…And because they are paid so much more; they are more valuable! A circular logic, of sorts…some kind of circular thing…

I thought about your comment and my head exploded.

The NHS is an organization with no marketing and sales needs.

It is a service organization, which is skilled people intensive, and the people subject to peer review.

Why does it need a CEO?

Sales and Marketing are ferociously expensive. The NHS needs to have no such expense.

The NHS is an organization with no marketing and sales needs.

It is a service organization, which is skilled people intensive, and the people subject to peer review.

Why does it need a CEO?

I remember, way back when, when the college district I was working in decided that their CEO needed to be paid as well as the CEO in the neighboring (and richer) district. I wrote an op-ed that that was all well and good but … why weren’t the qualifications and accomplishments of the two CEOs also included in the comparison, which I went ahead and did (there really was no comparison, the two sets of accomplishments could not have been more disparate). I heard from a Board member afterward that they hadn’t consider doing that and was a bit chagrined at having been duped by the CEO.

It was interesting to me that there were standard procedures for hiring and firing faculty and staff and union negotiations to set salaries and working conditions, but the CEO “negotiated” with the Board for his/her salary. There was no “opposition” or public advocate involved. This has always been part of the problem. CEOs consider their #1 responsibility to be Board management.

Excellent point made by Yves in her preface above re non-profit hospitals. Meanwhile, South Carolinians around the capital city are now reading this “sad news” from the state’s largest non-profit hospital system.

https://www.wltx.com/mobile/article/money/business/prisma-health-layoff-streamline-staff-southcarolina/101-2ba70532-7d6d-4721-b03b-318c99e927e7

CEOs in the private sector have by law one task – to increase shareholder value. Management in the public sector much consider multiple stakeholders. If there are only two stakeholders, the complexity doubles; if three it triples and so on. The reason the private sector seems simple is because it is simple. To reduce labor costs, it is the duty of management to seek cheaper labor, which right t now is in China, with terrible long term consequences for social disruption elsewhere. The public sector is just orders of magnitude more complicated. And now the private sector is producing in the direction of planet-wide destruction because it is not even obliged to consider the problem of its own waste.

This is a myth.

From Cornell Law School;

( BURWELL v. HOBBY LOBBY STORES, INC. )

And;

There is no law requiring focus on shareholder value.

From Cornell Law School;

Pure myth, or BS depending on your sense of charity towards ignorance.

Moderation is cramping my lack of style.

>>”CEOs in the private sector have by law one task – to increase shareholder value.”

Please go to the search box to the right, and type “shareholder value” for some excellent refutations of this statement. Links in articles going back decades are included in the articles.