By Lambert Strether of Corrente

In my perambulations through the biosphere, I have not yet entered the animal kingdom, so I thought perhaps it was time.[1] Why locusts? Because the Horn of Africa is experiencing one of the world’s periodic locust invasions, and a Plague of Locusts seems very on brand for 2020 so far. From Science Direct:

Schistocerca gregaria the desert locust is a species of locust. Plagues of desert locusts have threatened agricultural production in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia for centuries. The desert locust is potentially the most dangerous of the locust pests because of the ability of swarms to fly rapidly across great distances. It has two to five generations per year.

(We’ll get to “gregaria” in a moment.) Since writing “desert locust” would get tiresome, when I write “locust,” “desert locust” is what I mean.

Locusts are “the oldest migratory pest in the world“; the Bible has a good deal of information about them. For example, locusts, individually, are nutritious. Matt 3:4:

4 And the same John had his raiment of camel’s hair, and a leathern girdle about his loins; and his meat was locusts and wild honey.

Locusts, when swarming, also have an interesting social structure (as we shall see). Proverbs 30:27:

27 The locusts have no king, yet go they forth all of them by bands.

Finally, swarming locusts are often seen as symbols of evil and harbingers of change in the social order: Exodus 10:1,4, 12-14:

1 [ The Eighth Plague: Locusts ] Now the Lord said to Moses, “Go in to Pharaoh; for I have hardened his heart and the hearts of his servants, that I may show these signs of Mine before him, 4 Or else, if you refuse to let My people go, behold, tomorrow I will bring locusts into your territory….12 Then the Lord said to Moses, “Stretch out your hand over the land of Egypt for the locusts, that they may come upon the land of Egypt, and eat every herb of the land—all that the hail has left.” 13 So Moses stretched out his rod over the land of Egypt, and the Lord brought an east wind on the land all that day and all that night. When it was morning, the east wind brought the locusts. 14 And the locusts went up over all the land of Egypt and rested on all the territory of Egypt. They were very severe; previously there had been no such locusts as they, nor shall there be such after them.

(Of course, in the time of Moses, COVID-19 was not known. Or private equity.)

Skipping over the nutritional value of locusts (“They’re healthy; they’re plentiful; they’re kosher“), we’ll first look at the extent of today’s locust swarms. Then we’ll look at how locust swarms form and move (all without a king, as the bible says). Next, we’ll look at possible effects of this year’s locust invasions. Finally, we’ll look at locusts, climate change, and failed states.

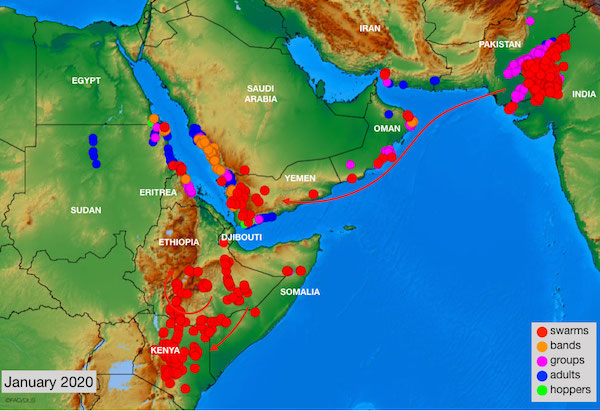

Here is the extent of locust swarms in 2020 so far, which the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) regards as “alarming”:

(I don’t know what the arrow from India to the Horn of Africa signifies; the FAO does not say that today’s invasions began in India, and I don’t think locust swams fly across the ocean. Perhaps individuals are carried by wind?) And soon there will be many more swarms. Deutsche Welle:

The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) warned Sunday that nymph (baby) desert locusts maturing in Somalia’s rebel-held backcountry, where aerial spraying is next to unrealizable, will develop wings in the “next three or four weeks” and threaten millions of people already short of food.

Once in flight and hungry, the swarm could be the “most devastating plague of locusts in any of our living memories if we don’t reduce the problem faster than we are doing at the moment,” said UN humanitarian chief Mark Lowcock.

The locusts were now “very hungry teenagers,” but once mature, their progeny would hatch, generating “about a 20-fold increase” in numbers, warned Keith Cressman, FAO locust forecasting officer.

Here are images of a locust swarm in Pakistan; there are similar images from the Horn of Africa:

In pics: locusts swarming in eastern Pakistan's Punjab Province. pic.twitter.com/M1Y6D5OxOG

— People's Daily, China (@PDChina) February 16, 2020

So, how do locust swarms form and move? I had thought, as I had done with previous excursions into the biosphere (mangroves, estuaries, soil) to seek a classification system, and then fit locusts within them. In fact, a locust is a grasshopper (with big hind legs for leaping, like crickets) that under certain environmental conditions becomes “gregarious.” I hate to quote Wikipedia, but this really is the best explanation I could find in my research:

Locusts are the swarming phase of certain species of short-horned grasshoppers in the family Acrididae. These insects are usually solitary, but under certain circumstances become more abundant and change their behaviour and habits, becoming gregarious. No taxonomic distinction is made between locust and grasshopper species; the basis for the definition is whether a species forms swarms under intermittently suitable conditions. In English, the term “locust” is used for grasshopper species that change morphologically and behaviourally on crowding, forming swarms that develop from bands of immature stages called hoppers. The change is referred to in the technical literature as “density-dependent phenotypic plasticity”. These changes are examples of phase polymorphism; they were first analysed and described by Boris Uvarov, who was instrumental in setting up the Anti-Locust Research Centre

Swarming behaviour is a response to overcrowding. Increased tactile stimulation of the hind legs causes an increase in levels of serotonin. This causes the locust to change colour, eat much more, and breed much more easily. The transformation of the locust to the swarming form is induced by several contacts per minute over a four-hour period…. When desert locusts meet, their nervous systems release serotonin, which causes them to become mutually attracted, a prerequisite for swarming.

The mutual attraction between individual insects continues into adulthood, and they continue to act as a cohesive group. Individuals that get detached from a swarm fly back into the mass. Others that get left behind after feeding, take off to rejoin the swarm when it passes overhead. When individuals at the front of the swarm settle to feed, others fly past overhead and settle in their turn, the whole swarm acting like a rolling unit with an ever-changing leading edge. The locusts spend much time on the ground feeding and resting, moving on when the vegetation is exhausted. They may then fly a considerable distance before settling in a location where transitory rainfall has caused a green flush of new growth.

(The brain of a gregarious locust is 30% larger than a solitary locust’s. Locusts also, apparently, have an internal “sky compass,” but there’s no evidence that they navigate, as opposed to simply heading downwind or seeking greenery.) Locusts — and I can easily say this, since I am not a farmer whose fields are being eaten by them — are truly a wonder of nature. (Also, “density-dependent phenotypic plasticity” and “phase polymorphism” are surely Words of the Day, somewhere.) Locust swarms can be truly enormous. From the Economist, one swarm contained “nearly 200 billion of the creatures and occupied a space in the sky three times the size of New York City.” Who needs a king when you have serotonin?

Turning to the effects of locust swarms, food security for millions is at risk (and East Africa has 19 million people are already food insecure)[2]. From the BBC:

The East African region could be on the verge of a food crisis if huge swarms of locusts devouring crops and pasture are not brought under control, a top UN official has told the BBC.

A massive food assistance may be required, Dominique Burgeon, director of emergencies for the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), said.

Ethiopia, Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda are affected.

There are fears that the locusts – already in the hundreds of billions – will multiply further.

The FAO says the insects are breeding so fast that numbers could grow 500 times by June.

From the Guardian:

The desert locust is considered the world’s most destructive migratory pest. A single locust can travel 150km and eat its own weight in food – about two grams – each day. A swarm the size of New York City can consume the same amount of food in one day as the total population of New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

What we are seeing in East Africa today is unlike anything we’ve seen in a very long time. Its destructive potential is enormous, and it’s taking place in a region where farmers need every gram of food to feed themselves and their families. Most of the countries hardest hit are those where millions of people are already vulnerable or in serious humanitarian need, as they endure the impact of violence, drought, and floods.

We have acted quickly to respond to this upsurge. Local and national governments in East Africa are leading the response, and our respective offices are working closely together to keep this outbreak under control. The UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs has released $10 million from its Central Emergency Relief Fund to fund a huge scale-up in aerial operations to manage the outbreak.

The FAO is urgently seeking $76 million from donors and other organisations to help the affected countries fight the outbreak. The amount required is likely to increase as the locusts spread.

$76 million doesn’t seem like a lot (reminding me of the world’s collective failure to fund the development of vaccines for, e.g., COVID-19). Particularly since the Return On Investment, if that’s how you want to think about it, is enormous. From the Associated Press:

Major locust outbreaks can be devastating. One between 2003 and 2005 cost more than $500 million to control across 20 countries in northern Africa, the FAO has said. It caused more than $2.5 billion in harvest losses.

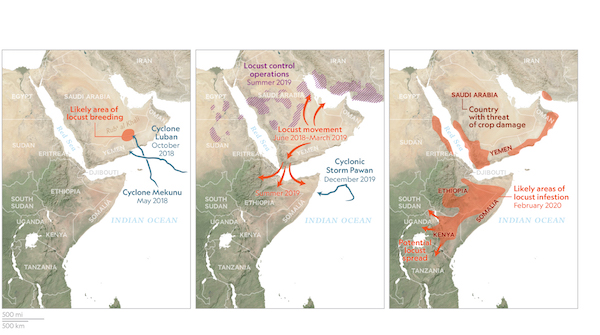

So we’ve seen how swarms of gregarious locusts originate, and their effects. But what triggers the swarms? Environmental effects. For example, climate change. The National Geographic has a fine explanation that includes this map:

(Click through for a larger version.) They explain:

Experts say a prolonged bout of exceptionally wet weather, including several rare cyclones that struck eastern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula over the last 18 months, are the primary culprit. The recent storminess, in turn, is related to the the Indian Ocean Dipole, an ocean temperature gradient that was recently extremely pronounced, something that’s also been linked to the devastating bushfires in eastern Australia.

Unfortunately, some experts say it may be a harbinger of things to come as rising sea surface temperatures supercharge storms and climate change tips the scales in favor of circulation patterns like the one that set the stage for this year’s trans-oceanic disasters.

“If we see this continued increase in the frequency of cyclones,” says Keith Cressman, senior locust forecasting officer with the Food and Agriculture Organization, “I think we can assume there will be more locust outbreaks and upsurges in the Horn of Africa.”

According to Cressman, the desert locust crisis traces back to May 2018, when Cyclone Mekunu passed over a vast, unpopulated desert on the southern Arabian Peninsula known as the Empty Quarter, filling the space between sand dunes with ephemeral lakes. Because desert locusts breed and reproduce freely in the area, this likely gave rise to the initial wave. Then, in October, Cyclone Luban spawned in the central Arabian Sea, marched westward, and rained out over the same region near the border of Yemen and Oman.

Then the locusts started to migrate. By the summer of 2019, swarms were leapfrogging over the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden into Ethiopia and Somalia, where they enjoyed another bout of successful breeding in subsequent months, Cressman says. This might have been as far as the locusts got were it not for the fact that last October, East Africa experienced unusually widespread and intense autumn rains, which were capped in December by a rare late season cyclone that made landfall in Somalia. These events triggered yet another reproductive spasm.

And if I wanted to control the outbreak — insecticides do work against locusts — then having the locusts make landfall in Somalia is not what I would have chosen. Because Somalia is a failed state:

Small and wingless, the hopping young locusts are the next wave in the outbreak that threatens more than 10 million people across the region with a severe hunger crisis.

And they are growing up in one of the most inaccessible places on the planet. Large parts of Somalia south of this semi-autonomous Puntland region are under threat, or held by, the al-Qaida-linked al-Shabab extremist group. That makes it difficult or impossible to conduct the aerial spraying of the locusts that experts say is the only effective control.

(Of course, states can fail in any number of ways, as we have seen recently in China.)

In past posts, I would point to or recommend some form of mobilization to prevent or mitigate environmental disaster; but there doesn’t seem to be a way to mobilize against locusts, except at the state level (or, I suppose, God level). Kenyan farmers, for example, are attempting to scare the locusts away with loud noises, like drumming or shouting. These measures seem unlikely to be effective. I can only hope that the donor class stumps up, and FAO gets its $76 million.[3]

NOTES

[1] I previously cross-posted on locusts in East Africa, but found the lack of detail very frustrating, so this post tries to remedy that.

[2] There is little information on long-run, life-long effects of locust invasions, although educational attainment of children is affected.

[3] I believe that locusts stop swarming when the weather cools. But that’s a long way away.

Locust(s) in the Bible

I’m trying to decide who Moses is, who Pharoah is, and what the locusts represent. To wit: “as symbols of evil and harbingers of change in the social order”.

For if you refuse to let My people go, behold, tomorrow I will bring locusts into your territory.

Reading #1: Bernie is Moses and DJT is Pharoah. But what are the locusts?

Reading #2: Bloomberg is Moses and DJT is Pharoah. Locusts could be Bloomberg’s dollars (near enough anyway, the latest swarm contained 365 billion insects). They lay waste to the land, eat everything, and leave nothing behind. “They will eat every tree which sprouts for you out of the field” Exodus 10: 3-5. And the people he wants “let go” would be the children of Israel, Bloomberg’s spiritual homeland.

” The desert locust is considered the world’s most destructive migratory pest “,

Locusts & all the other non-members of the human race would if they could probably disagree with that assessment.

A 4 minute BBC , Planet Earth segment about the desert locust. They eat every green plant in their path. Their eggs can lie dormant in the ground for 20 years, hatching when environmental conditions are right.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6bx5JUGVahk

Thank you for your highlighting this deeply troubling issue, Lambert. Fascinating physiological changes that occur in these insects, including their release of serotonin and related swarm behavior. Experienced a locust swarm firsthand years ago in an agricultural region of Pakistan highlighted on the FAO map and in the embedded tweet. Hard to imagine until one has seen it, and the swarm I witnessed was of relatively modest size. As the article and photos from CBC Radio described, this is prospectively catastrophic for the people in the region.

Apparently they’ve made it to China’s border (per Daily Star, i know).

The mediterranean locust is not as destructive in part because the terrain is more ecologically diverse than the desert. The same with locusts in Southamerican plains or Madagascar. Pheromones have been proposed as a more eco-friendly alternative to insecticides in some cases. Anyway because Somalia is Somalia,because the desert locust is the desert locust (brilliant, isn’t it?), and because weather, this one looks to be epic.

What about using nets as a barrier to protect at least some cultures or is this just another stupid idea brought by insomnia?

Don’t be mean to my old friend Insomnia. And I think that smaller scourges like flocks of birds have dealt with by nets, but this is likely a gigantic flying mountain of locusts. The insects would probably crush any netting ever and anyways we are also talking about really poor people who don’t have much resources at all. Too bad that the American military could not do some good by going after the actual terrorists in Somalia that would interfere with the bug spraying over the breeding areas of the locusts.

Considering nutritional value of locust this plague might just be a blessing in disguise.

I would worry that locust porridge doesn’t have a long shelf life.

Dried and freeze-dried crickets (used a lot as pet and chicken food) lasts for years if stored in a dry place.

No, locusts are higher up the food chain. Rough and ready rule is going one level up means you get only 10% of the calories if you’d eaten at the level below. Obviously, there is still big variation (chickens are very efficient compared to cows…)

And locusts probably very bad on that scale by virtue of how much they consume every day.

In the phrase “locusts and honey”, “locusts” refers to a fruit, not an insect.

LOCUST Any of several trees of the pea family bearing long pods, especially the black locust, honey locust, and carob.

Yes they can fly across the sea. When I lived in Trinidad, some turned up from W Africa, must have been flying for about 5 days.

If human activity in East Africa and environs could do it – I assume it would already have happened in those highly populated & ‘not-particularly-worried-about-the-environment’ areas – but its always fascinated me how locust plagues in the US just…disappeared.

The Rocky Mountain Locust theorized to have been driven to extinction by the ubiquitous plowing and changes wrought upon the plains environment by all the settlement and agricultural changes: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rocky_Mountain_locust

From an 1875 swarm ‘estimated at 198,000 square miles’ to just….gone. extinct. extirpated.

If the rainfall from cyclones helps provide the water for locus swarms, its easy to see why ancient people took locus to be divine punishment – there worst swarms come after an area has been slammed by cyclones. It would be hard not to see this all happening in your area consecutively back in the day and not conclude “wow god must be very angry with us.”

They say that they are tasty and healthy if cooked properly. Drone deep fryers maybe?

Crickets are certainly very tasty. They’re a bit savoury, like the flavour of potato crisps (US potato chips?) or roasted peanuts, and kind of fry in their own oil. They’re often caught at night using lights and nets.

Unfortunately, not much use for getting rid of swarms of zillions.