By Jerri-Lynn Scofield, who has worked as a securities lawyer and a derivatives trader. She is currently writing a book about textile artisans.

Earlier this month, US Public Interest Group (US PIRG) published a short squib discussing one modest recent development in the battle over the right to repair, LOBBYING AGAINST RIGHT TO REPAIR IS RISKY. The post concerned Comp TIA, which certifies repair and IT technicians.

Alas, although Comp TIA provides repair services, the organization found that when it lobbied in a manner that was consistent with its pro-repair orientation, its advocacy upset some of its customers.

Here I’m going to reproduce most of US Pirg’s post, as I think this is an important and reasonably optimistic development, which deserves wider attention. Advocates of the right to repair need to celebrate the small victories they can eke out, as the forces arrayed on the opposing side are vast and powerful, despite the inherent popularity of right to repair perspectives.

Right to Repair laws, which make it easier for consumers to fix their own stuff, are broadly popular with the public. So when companies lobby against it, it can upset their customers. CompTIA, a leading provider of certifications for repair and IT technicians, found this out the hard way.

As Right to Repair aims to expand opportunities for repair technicians, you might expect that CompTIA would support the campaign. After all, 96 percent of hiring managers in the IT repair field use their A+ certificate as recruitment criteria. With this huge portion of the technicians CompTIA certified, they have built a very visible presence among repair technicians.

Instead, CompTIA was one of the leading groups advocating against Right to Repair reforms. In doing so, they opposed the idea that manufacturers should provide access to the parts and service information needed to repair modern gadgets, a policy that would help many of their members.

But earlier this month, CompTIA changed their tune.

Now, the reason for this shift was a change among the policy views of its membership, catalyzed by increased scrutiny of its lobbying practices arising from Right to Repair hearings:

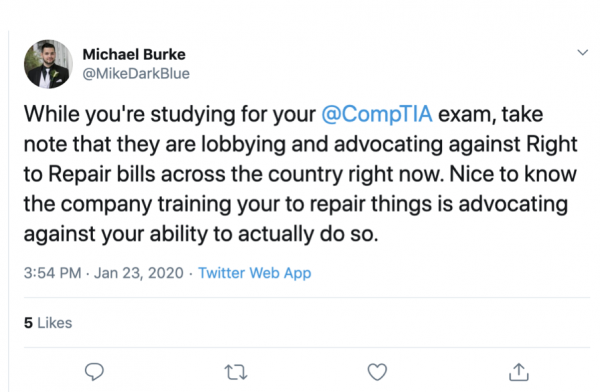

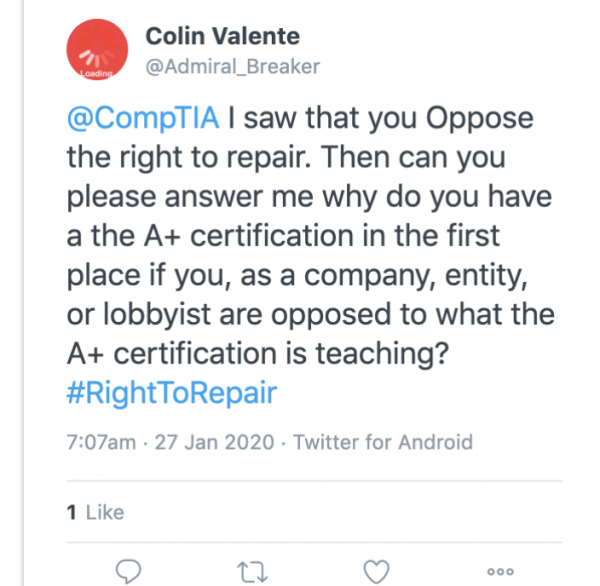

Louis Rossmann, a repair shop owner and Right to Repair advocate, has built a significant YouTube following that includes many CompTIA members. His recent coverage of Right to Repair hearings increased scrutiny on the trade organization’s lobbying efforts, and holders of the A+ certification started speaking out. They took to Twitter with confusion and outrage, and were among the more than 3,000 individuals to sign Rossmann’s petition rebuking the trade group’s lobbying practices.

I must say I find it somewhat odd that an organization that seeks to provide repair and certification services would lobby to the contrary. so COMP TIA’s policy shift now seems to be a bit more aligned with the natural order of things.

CompTIA quickly took notice. Right to Repair advocates used the public outcry to convince CompTIA to stop lobbying on the Right to Repair issue, telling Rossmann, “We’re stepping back from the debate going forward.”

The reason CompTIA was simultaneously representing repair technicians and lobbying against Right to Repair is potentially linked to the 2014 acquisition of the lobbying firm TechAmerica. At that time, CompTIA was primarily focused on its education and certification business, but had little influence on public policy. They acquired TechAmerica to amplify the “industry’s already powerful voice in Washington, D.C.”

Apple, one of the leading voices opposed to Right to Repair reforms, is reported to be a client of that lobbying work, and has lobbied alongside CompTIA in states including California.

CompTIA bowing out of the Right to Repair conversation is the latest demonstration of the broad and deep support for these reforms. With Right to Repair legislation in Massachusetts and Hawaiialready clearing important hurdles, and the American Farm Bureau making the issue a legislative priority, the campaign has built significant momentum in the early days of 2020.

Getting in the way of that momentum, even when funded by a trillion dollar conglomerate, is risky, and industry is starting to buckle.

******

Another thing I want to mention: the right to repair and the US military. Readers may recall that last November, Captain Elle Ekman published a NYT op-ed that shocked even this cynical observer of US politics, Here’s One Reason the U.S. Military Can’t Fix Its Own Equipment:

As I posted shortly shortly thereafter, Lack of Right to Repair Limits Ability of US Military to Maintain its Own Equipment:

Apparently, even the US military doesn’t enjoy a right to repair for materiel it purchases, and instead must ship some equipment back to the states, for maintenance and repair by the original manufacturer, rather than fixing it locally.

No joking.

Why?

Over to Captain Ekman’s op-ed:

A few years ago, I was standing in a South Korean field, knee deep in mud, incredulously asking one of my maintenance Marines to tell me again why he couldn’t fix a broken generator. We needed the generator to support training with the United States Army and South Korean military, and I was generally unaccustomed to hearing anyone in the Marine Corps give excuses for not effectively getting a job done. I was stunned when his frustrated reply was, “Because of the warranty, ma’am.”

At the time, I hadn’t heard of “right-to-repair” and didn’t know that a civilian concept could affect my job in the military. The idea behind right-to-repair is that you (or a third-party you choose) should be able to repair something you own, instead of being forced to rely on the company that originally sold it. This could involve not repairing something (like an iPhone) because doing so would void a warranty; repairs which require specialized tools, diagnostic equipment, data or schematics not reasonably available to consumers; or products that are deliberately designed to prevent an end user from fixing them.

I first heard about the term from a fellow Marine interested in problems with monopoly power and technology. A few past experiences then snapped into focus. Besides the broken generator in South Korea, I remembered working at a maintenance unit in Okinawa, Japan, watching as engines were packed up and shipped back to contractors in the United States for repairs because “that’s what the contract says.” The process took months.

…

I also recalled how Marines have the ability to manufacture parts using water-jets, lathes and milling machines (as well as newer 3-D printers), but that these tools often sit idle in maintenance bays alongside broken-down military equipment. Although parts from the manufacturer aren’t available to repair the equipment, we aren’t allowed to make the parts ourselves “due to specifications.”The right to repair has become more prominent on the political agenda, with both Senators Sanders and Warren endorsing versions of the concept, as has the editorial board of the New York Times (see Right to Repair Initiatives Gain Support in US). The Federal Trade Commission debated the idea during a workshop this summer, and Ekman and captain Lucas Kunce submitted a comment letter, Comment Submitted by Major Lucas Kunce and Captain Elle Ekman, which provides details that support her NYT op-ed.

Now, for those readers who missed my earlier post – or who read it. and fancy an update – this week Popular Mechanics published a piece that makes clear that right to repair in the military is a persistent problem, which has not gone away:

U.S. troops in the field are running up against increasingly restrictive licensing agreements signed by the Pentagon that limit their ability to service their own equipment. This presents a readiness and equipment confidence issue, which could make American forces less effective in wartime.

An article at Foxtrot Alpha takes a look at the “right to repair” issue faced by today’s military. The article reports on how changes to the military procurement system allowed the Pentagon more leeway in buying civilian equipment—a good thing by any measure. Unfortunately, those agreements often include similar versions of the civilian warranty, which effectively prohibits civilians from servicing their own equipment.

The right-to-repair issue is relatively new in the world of consumer rights. Restrictive warranty agreements, from iPhones to John Deere tractors, often prevents consumers from making repairs to their own devices or having a third party perform the repairs without voiding the warranty. Manufacturers claim the warranties are necessary in order to ensure the repairs are done correctly, but the repairs are often expensive and more time consuming than allowing the consumer to do it.<

Even for those of us not already completely worn down by accounts of overpriced, bloated weapons systems not fit for purpose, the lack of an ability to repair military equipment – an absence of any military right to repair – is just another variation on the theme of how the US military manages to waste resources in new and ever more rococo variations.

I’ll close by suggesting that a right to repair is an idea whose time has come – for both civilian and military applications.

I repair my own stuff, dont care about threats from companies, nothing I cannot fix unless its just plain old finished.

I hope I don’t meet your self-repaired self-driving Tesla coming down the highway some day.

You can relax, no one who can repair their own machinery, or who thinks independently, would be dumb enough to buy a Tesla in the first place.

That’s for naive, credit addled minds that have no concept of value or what quality is. People who buy Teslas will be the first to be beaten, eaten and helpless when the SHTF.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H78AhRik04I&list=PLHgCeKJSmJdMTn1ppPvc50g8ia85dKXNH

It happens.

Don’t worry, the stock version doesn’t work either.

It would be extremely unexpected for self-driving, once it becomes a mass product and not just a toy of the technorati, to not be regulated and certified under the same sort of regime as designated emissions components already are, including on-board self-diagnostics and the exclusion of suspect sensor inputs from controlling the system.

Thanks for keeping us updated on this issue, Jerri-Lynn.

It’s an important attack vector on the neoliberal capitalism that is destroying our society.

As I was reading the post, the thought occurred to me that this kinda fits right in with Matt Stoller’s writing on monopolies. Companies want to keep control over every aspect of our daily lives so they can extract ever increasing profits, especially those firms that have monopolistic power.

And the military? Geez, you’d think that Pentagon procurement officials would realize how much trouble and expense is being wasted due to this issue. In a rational world the military could use it’s vast purchasing power to insist on changes to standard civilian warranties that would allow them to maintain their own machinery. I reckon if you have almost unlimited funds it doesn’t really matter, except to the soldiers in the field who have to do without until machinery can be shipped back and forth to the US. Sad! (And disgusting, but not entirely surprising.)

Of course, if you’re only consideration is maximizing profit, the soldiers and the general public can just go whistle in the wind.

“Boycott John Deere”

Gee, what a wonderful name for a new political party – “Right to Repair”!

It absolutely applies to the condition of the country at large – and voters should have a ‘right to repair’ the voting system, crapified as it now is! We are the ‘users’ of said system, so we should get to repair it!!!

We bought our Waterford Natural Gas Heater 30 years ago when we fixed up our new-to-us old house. I pushed for retiring the traditional fireplace and sticking a freestanding stove w/fake logs in front, closing off the chimney after running the new vent pipe up it. It was great backup heat when/if the furnace didn’t work, in fact it could heat the entire house, built in 1910.

One of the nice features was the SIT valve, enabling the burners to quietly reduce in flame size as opposed to booming on and off. We had moved from a different old home that had an oil furnace w/a heat exchanger that boomed on relentlessly then chug-chugged the hot air through dusty vents until “bang” it all shut off, soon to repeat the cycle. Boom chug-chug. Boom chug-chug. Off to see the allergist!

Blissfully our new old home had old and quiet hot water radiators that did not blow dust throughout the house. Radiators are great, but any thermal mass heat system is an improvement over blowing nasty hot air all over.

After 20 years of running well, providing both back-up and comfort, the Waterford died. I called the guys we had bought it from. They couldn’t fix it. “They don’t make parts for this one anymore.”

I shut off the gas valve and with trepidation ventured to fix it myself. I laid an old towel in front, opened it up, took out the ceramic logs… the burners looked simple enough, steel tubes w/holes… the thermocouple looked simple… the pilot flame kept it warm and if not, the thermocouple would, using milivolts, shut off the gas for safety. After I replaced the thermocouple (cheap and easy) and the stove still shut itself off, I determined that the gas valve was the culprit. I called the guys again. “They don’t make parts for this one anymore.”

From the “they don’t make parts” store I bought a newer, crappier stove that was bristling w/safety and convenience features destined to confuse and fail, along w/yet another remote controller. I put it in the garage. I dismantled the old stove, being too heavy to carry out. I looked at the pieces sadly arranged on the living room rug. Damn. This stove is beautiful and like an old friend. Made in Ireland of brown-red enameled steel, aesthetic, functional and simple. Yeah and it wasn’t cheap.

I looked at the old SIT valve in my hand, typed some numbers from it into ebay and found the exact valve NOS (New Old Stock) valve for $200. What the hell. I ponied up paypal.

When it arrived, once again w/trepidation (I’m not a mechanic) I installed the valve, hoping I wouldn’t burn the house down and reassembled the stove. It ran great. I gave away the new stove in the garage to one of our sons. It’s in his garage.

There have been a few issues and it requires attention and adjusting, but what old friendship does not? If it dies again I will revive it.

Great story. Thank you.

How much of modern repair would include access for source code?

Much equipment today carries embedded programming, code. If one argues for right to repair than that should include source code, as I suspect that many pieces of equipment which contain code cannit be repaired without that access.

The source code could contain the “crown jewels” of the product, making replication easy, or include expensive “options” enabled by setting a few bits, or be the “crown jewels” of the produce, or reveal the “fix hardware deficiencies in the code” mentality exhibited by Boeing.

To provide people with the right-to-repair with modern equipment, must include copies of the source code for embedded programming, to enable the end user to correct any fault.

And that opens up a whole new world of patches, hacks and liability work into the world of “fix it yourself.”

Modern fix it yourself is more than nuts, bolts and spare parts, it includes embedded programming.

That’s exactly the point that some manufacturers make. To a lot of people ‘fix’ includes hack, alter, modify and otherwise do things that can cause both physical and economic damage… then the manufacturer ends up in court needing to prove that is was the fault of the ‘fixer’.

“Right to Repair” is a kneejerk slogan soaked in prejudice against the big companies who must, perforce, be ‘evil’ and that kneejerk attitude fails to address the legitimate complexities of the question.

It makes me wonder whatever happened to personal responsibility? I take it for granted that I’m on my own when I get into something. If it goes wrong, I’m on my own and must eat the consequences.OTOH I’m actually qualified to do so, I do it for a living.

I think its not so much the owners as it is the ambulance-chasing lawyers who are the problem.

The ‘concern’ about the untrained trying to make repairs and failing doesn’t explain big industry attempts to shut down independent, A+ certified, and often brand certified repair shops. Big Corp is trying to shut down independent shops because they’re independent, they aren’t part of the corporate entity. It’s a strong arm tactic to make more money and drive competitors out of business, imo, and then price hike repair prices with monopoly control of access to repairs.

+1000

Right to repair is generally construed as the right of 1. anyone with requisite skill to remove/install components of some equipment, 2. without the manufacturer’s consent, 3. to restore it to the condition in which it was first sold. If embedded programming skill is required to repair a device, then at least one of these three statements is true: it was designed specifically to hinder reparability, which is a clear infringement on the right to repair; the components and information necessary to effect the repair are not readily available from the manufacturer or others, which is also a clear infringement on the right to repair; or you are trying to modify the device to a condition other than that in which it was first sold, which does not infringe the right to repair as construed above.

I agree that the right to modify or the right to hack is an important consequence of first-sale doctrines in “intellectual property”, and an intrinsically valuable touchstone in the freedom of the bound consumer-serf to produce value for themselves without permission of the market. But I feel it has consequences that reach deep into the entire consumer electronics value chain, is separate from the cause of reducing waste by improving the service life of consumer goods, and is unlikely to be significantly thwarted further in the course of implementing a right-to-repair, and so is better pursued under its own banner.

If I can read the ROM, then I can disassemble it and create a new one. Most of this programming is pretty simple. Depending what else is going on I usually can fix whatever it controls or now controls very easily. Great way to add features to older out of date products. Unless you’ve got a knack for it, or have the education and experience it can be frustrating. Everything always seems to be in the middle of something else. I found “Zen and the Art of Motor Cycle Maintenance” an excellent way to get out and avoid frustration. Once it clicks it can be quite a bit of fun.

Whew. Reverse-engineering assembly code from a ROM, especially given the now current use of surface mount and microcontrollers — sounds like entering a world of pain.

Thanks very much for this post. The idea a company certifying repair techs would then work against the repair techs’ economic livelihood – and not tell them – because it got in bed ,through an acquisition, with a Silicon Valley behemoth that’s against RTR is horrible. Very glad the repair techs won this round.

Also, glad military field personnel are speaking up about R2R negatively affecting readiness.

This is encouraging news.

correction: the lack of RTR is negatively affecting military readiness.

50 to 100 years from now, when industrial production slows to a crawl, everybody will have to make do with used gear. We will all live like Cubans with their 1950s era cars they fix endlessly.

RTR makes modern gear reusable in this ugly future.

I generally support the right to repair, but there are some kettles of worms:

– It used to be popular to redo the ROMs of stock automobiles to improve performance. If you wanted to show off on Queens Boulevard, you stopped off at one of the shops on Northern Boulevard near 69th and popped in new controller software. The worm is that these performance improvements violated emissions standards and possibly other safety standards. It’s even a more serious problem now since things like stability control in many cars is a software, not a hardware, feature. You’ve broken the oversteer correction code and slammed into a lamp post. Who pays for what?

– There’s the whole problem of computer security. If you want to build computers that operate securely, you have to make them hard to repair. Apple bundles a lot of security features into their T2 chip, and disconnecting the chip disables the whole system. Only Apple knows how to pair them up again, and for all I know it is actually impossible, but Apple eats the added cost. Back doors, like the maintenance and administration back doors in many server chips are attack surfaces that many would like to enclose. In theory, we want something like locksmith certification which is about more than simple technical knowledge, but why be secure only in practice when one could be secure in theory instead?

It might help the right to repair cause to acknowledge these issues and address them. What kinds of repairs should people be able to do? Who is responsible if the repair causes subsequent problems? What kinds of repairs should void a warranty? If you’ve ever tried to something as simple as splicing a four wire USB cable, you know that the spliced cable is rarely as reliable at high transfer rates as the original. (My experience is that it is rarely usable for data transfer at all.) Is this just big USB cable profiteering or am I an idiot trying to save five bucks?