Yves here. What is particularly appalling is that, as you’ll read, a winning bidder wanting to turn the refinery land into a real estate development is now facing having his offer rejected by hidden interests who want to keep the refinery going. There also appears to be no particular unique economic value to this refinery. And there’s no indication that these competitors even offered more! What sexual favors were exchanged for this to have happened?

Before it exploded last June, Philadelphia Energy Solutions (PES) — the largest crude oil refinery on the East Coast — was processing 335,000 barrels of oil each day. It was also producing some of the highest levels of benzene pollution of any refinery in the country, according to a new report by nonprofit watchdog group the Environmental Integrity Project.

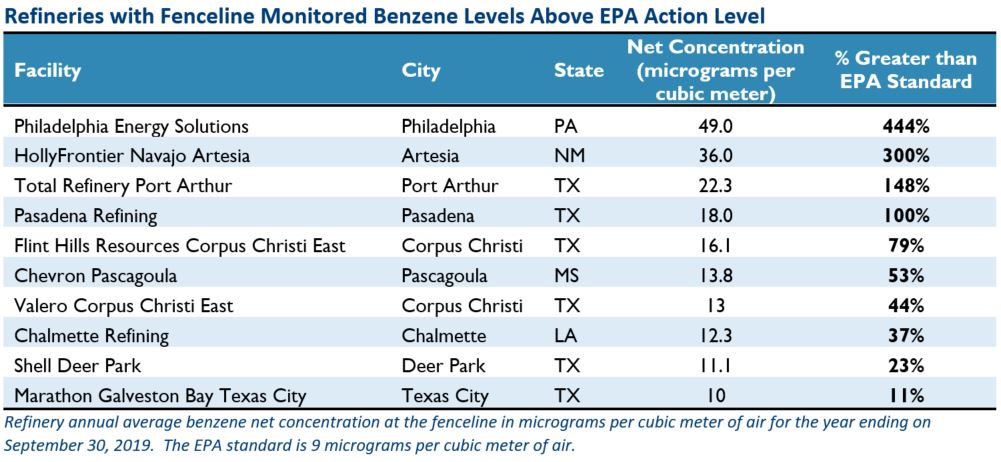

The report, which follows a recent investigation of PES’s benzene pollution by NBC News, found that 10 refineries across the U.S. were releasing cancer-causing benzene into nearby communities at concentrations above the federal maximum in the year ending in September 2019. Under 2015 EPA rules, facilities are required to investigate where their toxic emissions are coming from, then take immediate action to reduce impacts — both of which PES failed to do. The refinery had an annual average net benzene concentration that was more than five times the EPA standard, beating a long line of refineries in the oil-friendly state of Texas. Out of the 114 refineries that the group examined across the country over the course of a year, PES emitted the highest levels of benzene.

That includes the period after the refinery was shut down following the explosion.

Residents of South Philadelphia say they were awakened in the early hours of June 21, 2019 by a loud boom. Large pieces of debris poured down on the streets followed shortly by the smell of gas. Neighbors looked out their windows and saw clouds of dark smoke billowing from the nearby complex, which already had a history of safety issues.

For a while, that seemed to be the end for the refinery. Rather than make repairs and clean up the mess after the June incident, PES shut down the facility and filed for bankruptcy. The company put the 1,300-acre waterfront property up for sale, either to be maintained as a refinery or to be turned into housing or mixed-use development. And last month, after a closed-door auction in New York City, Hilco Redevelopment Partners, a Chicago-based real estate company, was the selected winner. But just when it seemed the PES refinery complex would shut down for good, the Trump administration got involved, offering its help last week to spurned bidders who are challenging Hilco’s victory because they want to keep the property processing crude oil.

The idea of keeping the refinery active doesn’t sit well with some environmental activists, especially in light of the new benzene report.

“Today’s report is just one more factor and data point on why this plot of land should not be put back into a use that puts local communities at risk,” said David Masur, executive director of PennEnvironment, a statewide environmental group working for clean air and water.. “Whether it’s an explosion or a constant threat of pollution from known carcinogens, the choice of putting a refinery there is just too dirty and dangerous.”

A Community Fuming

South Philadelphia has long been a diverse cultural hub for the city. It also faces multiple sources of pollution. In addition to the PES refinery complex, the largest source of particulate air pollution in Philadelphia and a repeat violator of the Clean Air and Water Acts, South Philly also has major arterial highways, the Philadelphia International Airport, large industrial factories, and other processing facilities.

More than 5,100 people live in the area within a one-mile radius of the PES refinery. Most of the residents are black, and 70 percent of the residents live below the poverty line. These residents also suffer from disproportionately high rates of asthma and cancer.

In a letter sent to the City of Philadelphia Refinery Advisory Group — a group the city created in wake of the June 21 explosion — at the end of October 2019, Drexel University researchers summarized the health impacts of living near the PES refinery based on data they’d gathered. They listed negative birth outcomes, cancer, liver malfunction, asthma, and other respiratory illnesses. They also included mental health impacts such as stress, anxiety, and depression that come with living near a large industrial site like PES.

“Because the PES refinery is immediately surrounded by several neighborhoods, communities near the refinery will be disproportionately affected by compounds released by it,” Kathleen Escoto, a graduate student at the Dornsife School of Public Health at Drexel who was one of the authors of the letter, told Grist. “If the refinery released the highest levels of benzene in the country, especially considering its proximity to densely-populated areas, then the burden of disease that the refinery has on the surrounding communities is even worse than we thought.”

Benzene, a colorless chemical with a somewhat sweet odor that evaporates from oil and gas, is used as an ingredient in plastics and pesticides. According to the U.S. Center for Disease Control, exposure to benzene can cause vomiting, headaches, anemia, cancer, and in high doses, death.

Philly Thrive, a grassroots environmental justice group that has been raising awareness about the public health costs of living near a fossil fuel facility since 2015, has been organizing community members from South Philadelphia to fight against PES and to ensure that they have a seat at the decision-making table.

“Part of what Philly Thrive has faced when residents tell their stories about the impact of the refinery on residents’ health is confrontation from politicians and leaders, who challenge our personal stories, lived experiences, and wisdom,” said Philly Thrive organizer Alexa Ross. “It’s always been offensive, perplexing and confusing to be challenged on the basis of facts.”

The Refinery’s Fate

Despite the Trump administration’s efforts to keep the refinery in operation, the fate of the land is still up in the air. On Thursday, Philly Thrive organized a call bank session for members to make phone calls to Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney and the Industrial Realty Group, an alternative bidder on the property that wants to keep it as a refinery. They cited the new report as part of their reasoning that the refinery should remain closed.

“This report just leaves us fuming, speechless, dumbfounded, and reeling about how residents have known for so long that the refinery has been killing generations of Philadelphians, but politicians still ask us to prove it,” Ross said.

“Imagine if we actually have the right kind of air monitoring system we need,” she added. “Imagine what else would come to light about what facilities like the refinery has been doing to human health.”

A hearing to finalize the details of PES’s 11 bankruptcy sale is now scheduled for February 12 in Wilmington, Delaware.

I think that keeping this plant going has nothing to do whether it is economical or is needed but is simply has an ideological reason behind it. Just saw an example in the news just now where here in Oz the government wants to throw millions to get a coupla coal-fired plants up and running that investors will not have a bar of.

Something like this happened several years ago when a dirty coal plant was being shut down as being non-viable but the Coalition government was promising millions to the owners to keep it going. In the end they could not keep it open and so it closed.

https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/feb/08/private-investors-wont-touch-new-coalition-backed-coal-plant-labor-says

This Philadelphia refinery sounds like more of the same and once it reopens – it it does – then the argument used afterwards to keeping it open will be jawbs, jawbs, jawbs.

The government stepping in to keep an inefficient plant open just to provide workers with jobs reeks of socialism.

The problem with making the property a real estate development is pollution. The land it sits on has to be very polluted with toxic chemicals from decades of refining crude. To clean up this type of property is expensive beyond belief. I wouldn’t personally want to ever go onto this land. Even if it is cleaned up. The land in effect is useless until it is cleaned up. The question is who is going to pay the bill. Since they went bankrupt the polluter is off the hook. Developers won’t foot the bill but instead get taxpayers to pay the cost. It’s the American way.

A lot depends on the type of pollution and its distribution – I’m sure the developers aren’t completely stupid. Pollution within a refinery is most likely to be within hotspots rather than generalised (although much depends on the underlying geology – sometimes if you have a porous subsurface over an impermeable zone any hydrocarbon spillage with spread laterally). If its hotspots, then its not necessarily very expensive as you can design your way around the problems. In many cases, the most environmentally sensitive approach to subsurface contamination is to leave it untouched and design your way around it.

Much depends on the local building regulations of course, I really don’t know anything about how they approach this sort of thing in Pa.

IIRC, the Refinery is over 100 years old. Equipment – and locations – will have changed a lot through that time, and I’d bet the records are spotty. If Hilco thinks it knows where the contaminants are, they’re stupid or crazy. Plumes would have spread far, in unpredictable directions, across that time. Plant presumably produced leaded gas back in the day, so there will be heavy metals in there too. It will be a long time before it’s safe for children and other living things.

More likely that their lawyers assured them they would be able to develop selected areas (Schuylkill waterfront?) and foist off the rest of the mess onto someone else.

Agreed. The old Willow Grove Naval Air station has been closed for years, but the land is still vacant because of PFAS contamination. And that’s despite the area’s super high property values and a building boom!

The old Navy Yard in South Philly had contamination problems, too, from the buried fuel tanks, but the area is pretty well built up now. I wonder if they actually cleaned any of it up, and if so, who paid for it?

The EPA and US Navy did the heavy clean up of the Navy Yard before it was turned over to the city & PIDC (local public-private economic development corp) in 2000. If I wanted to rile myself up, I could write a treatise on the way Philly “incentivizes” development, but really have a hard time knocking the federal gov’t spending the money to perform major environmental clean up. Seems like a good use of its unlimited spending power, to me. There are also “innocent owner” clean up programs that vary state-by-state that help developers remediate polluted sites. I’d rather see the state (or more ideally, the feds) step in to make remediation viable than wait for “the market” to value the land highly enough for the site to merit clean up without that support.

Completely agreed with PK in the sense that a developer bidding on a project this large likely knew what they were getting into – this isn’t a case of a small-scale developer unknowingly buying a retail site where there was an unknown historic polluter like a dry cleaner or leaking underground tank in the vicinity. Anyone who has flown into PHL has seen and/or driven past the ugly monstrosity that is that refinery. It doesn’t take a trained eye to understand that needs to be an early and substantial part of your diligence process.

PFAS is an emerging contaminant that generally doesn’t have regulations set on it yet. For the military bases, one of the most common sources of it was firefighting foams, so fire fighting training areas as well as areas that had real fires are major sources. These are very common on many military bases.

Refineries aren’t that bad to clean up. Most of the contamination tends to be biodegradable compounds (like benzene) so in situ technologies like enhanced bioremediation (add nutrients and oxygen) and oxidation (inject compounds like peroxides to react with compounds) are very effective in providing for near-total destruction of most of the contamination present on these sites. Some soils will be contaminated with metals (especially lead, from leaded gasoline production) which is usually very immobile in soils, so capping with soils and pavements, in situ solidification with cement, or encapsulating in a landfill usually works very well. There will be local challenges, but probably well over half the site could be made ready for development within a handful of years.

Environmental remediation technologies are light years ahead of where we were in the 1980s. Refinery sites are commonly cleaned up across North America and re-used for numerous purposes cost-effectively.

Jackiebass, tou are correct.

I would not dream of buying or occupying any form of residential, office or even warehouse space on this property assuming it was “cleaned up”. I often think of Ft. Devons in Massachusetts as a classic example of these issues which has not worked out very well. This one pre-dates the Civil War.

One tragedy is we are going to have to have some continuing refining of petroleum into gasoline and other petro-chemicals as we transition or evolve our economies into more sustainable and clean modes to meet our collective and personal responsibilities as stewards of this great planet which is our home.

While I am not endorsing nor am I condemning the “Trump administration” (whoever that may be) or any other, on first blush, rebuilding a new refinery on this same site may make some sense.

The infrastructure in the “oil area” from pipelines to refineries within USA are nearly uniformly rather old and beyond engineered life. Thus, new ones are critically needed. Thus, we need to deal with these matters in a responsible manner.

This seems to be a very complex bankruptcy with a lot of moving parts. The union, the USW, also wants the plant reopened, and the competing bid was higher than the winning bid, I don’t know how common that is in bankruptcy filings. And the unsecured creditors, which appear mostly to be suppliers, are very unhappy, including over the decision to give the executives bonuses, including those that were given out between the fire and bankruptcy filing.

https://www.inquirer.com/business/bankrupt-philly-refinery-plan-flawed-creditors-reject-executive-bonuses-hilco-irg-20200207.html

It’s a messy, messy situation, but my guess is that the refinery will never reopen, regardless of the winning bidder. Trump is probably just using this as a way of appealing to blue collar workers.

I note the large presence of Texas sites on the top ten list of polluters. No surprise here, my state is a leader in pollution, and has been for years. The extremely high cancer rates on the Gulf Coast are just one of the many benefits.

Back when the State of Illinois had a somewhat functioning government including in the office of AG they shut down two notorious polluting refineries of Clark Oil (later Premcor, then Valero) in Blue Island Illinois (Chicago suburb) and Hartford Illinois. Don’t necessarily need the Fed EPA involved to do so.

Not related to oil refineries / benzene, but recently local neighbors to a commercial sterilization facility, Sterigenics in Wiilowbrook, IL, had a couple of years of “peasants with pitchforks” activism where they grilled the company, the IEPA, and local government about the massive gradual air emissions of ethylene oxide (carcinogen) over the course of many decades. The state was finally forced by the locals to close the place. The locals also did a nice job in tracing the ownership through the LLCs and private equity pirates, including a prior ownership stake by the most recent former governor. None of these people ever sh-t where they live. The people did not put up with allowing the state or local government agencies not taking responsibility / blame for allowing the conditions in the first place.

According to the U.S. Center for Disease Control, exposure to benzene can cause vomiting, headaches, anemia, cancer, and in high doses, death.

It is aromatic hydrocarbon. (Benzene ring). I understood all aromatic hydrocarbons are carcinogenic (Cause Cancer).

The enforcement provisions of the Clean Air Act (at least as I remember them) are devolved to the state, regional or local air quality boards. In this case the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Quality Bureau of Air Quality should have the responsibility for maintaining the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS). When the responsible agency demonstrates its inability to monitor or enforce the NAAQS or refuses to implement a plan to meet the NAAQS, that agency can be decertified and the responsibilty assumed by the EPA. This happened to the state of Ohio in the late nineties.

It seems that the there is no longer even a fig leaf of protection for the citizenry. Here is a clear case of point source pollution for which the mitigation is well known and easy (although perhaps expensive) to implement. It looks like complete dysfunction to me.

Couldn’t agree more – solutions do exist particularly when the point source is known. Again and again the problem is identified, the source known, the effects documented.

What is lacking is the will to protect the citizenry.