By Lambert Strether of Corrente

Readers may recall that I’ve written about edible forests in the past (2012; 2013; 2013; 2014; 2015) and it might be thought that the topic would provide a welcome respite from Coronavirus news. Not necessarily:

The Before: I'm social distancing at the moment by turning my partner's garden into an edible forest garden. Most of what is here was planted by the previous owners, and they covered most of the garden in cheap landscaping fabric and gravel. pic.twitter.com/uu1gure7B0

— Isaac Marsh (@isaac_laurence) March 21, 2020

So if you’re up for keeping your social distance for a few weeks or months, an edible forest — no matter the scale — might be just the project for you. What is an edible forest, you ask? I wrote:

What Is an Edible Forest?

I’m going to give this operational definition, sourced to Gaia’s Garden by Toby Hemenway, not because it’s the only possible definition, but because it creates a very clear picture in my mind of the possibilities (and, though I say it, the beauty):

The Seven – Layer Garden

An edible forest is a layered garden. The seven layers of a for est garden are tall trees, low trees, shrubs, herbs, ground covers, vines, and root crops. Here are these layers in more detail.

1. The tall-tree layer. The tall trees in an edible forest are mostly fruit and nut trees, such as apple, pear, plum, cherries, ch estnuts, and walnuts. There needs to be lots of space between the trees to let light in to the lower layers.

2. The low-tree layer. The next layer is made of smaller trees, such as apricot, peach, nectarine, almond, and mulberry. Dwarf varieties of bigger trees are also good choices for this layer. These trees can be pruned to have many openings to let lots of light through to the lower layers.

3. The shrub layer. This layer includes flowering, fruiting, and wildlife-attracting shrubs. Examples include blueberry, rose, hazelnut, and bamboo.

4. The herb layer. The “herbs” in an edible forest are plants with non-woody, soft stems. They can be vegetables, flowers, cover crops, cooking herbs, or mulch crops. They are mostly perennial, but sometimes gardeners choose to plant a few annuals .

5. The ground cover layer. These are very low plants that grow close to the ground, such as strawberries, nasturtiums, and thyme. They are very important because they make it difficult for weeds to grow.

6. The vine layer. In an edible forest , some plants, like grapes and kiwis, grow up the trunks of the trees.

7. The root layer. A forest garden grows both up and down. The last layer is plants that grow underground. These should be plants with shallow roots, like garlic and onions, which are easy to dig up without disturbing the other plants.

(In my own tiny practice, I have planned for #3, and not even thought about #6 (vines) or #5 (ground cover). #5 is especially important to me because weeding is work. I don’t like work.) And (as NC readers know) you don’t need a lot of land to start one

As I said, although this definition creates a very clear picture, it’s possible to derive the same result from a more principled and sophisticated approach, such as that provided by Dave Jacke and Eric Toensmeier’s Edible Forest Gardens, Volumes I and II, publshed by Chelsea Green Publishing (August 30, 2005). How could I not have known about this gorgeous book? (There are long-downloading PDFs online, from which I took the images that follow, but you really ought to buy this one.)

Since I’m pressed temporally — I have to finish up a coronavirus post, and some Water Cooler posts — I cannot do the book justice. Instead, I’ll make three points:

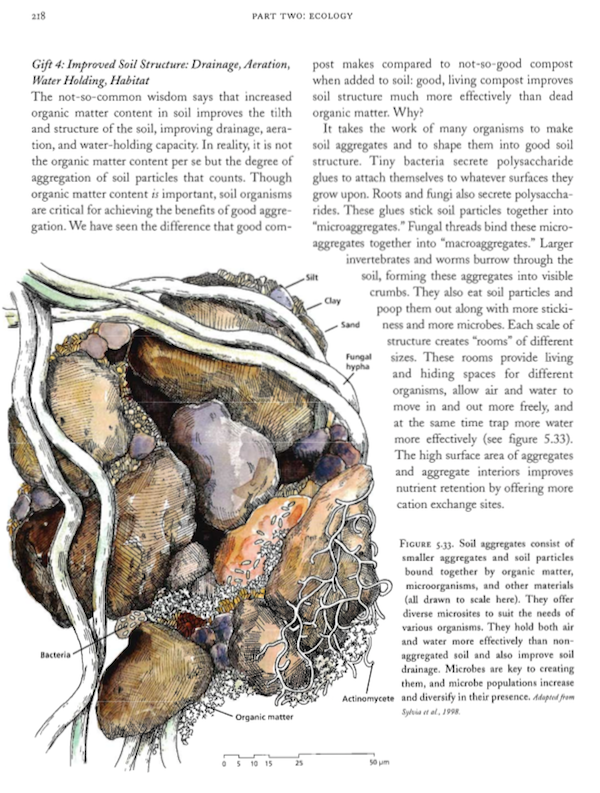

1. Edible Forest Gardens is indeed a beautiful book. I know we have soil fans on the blog; here is a lovely drawing of soil aggregates:

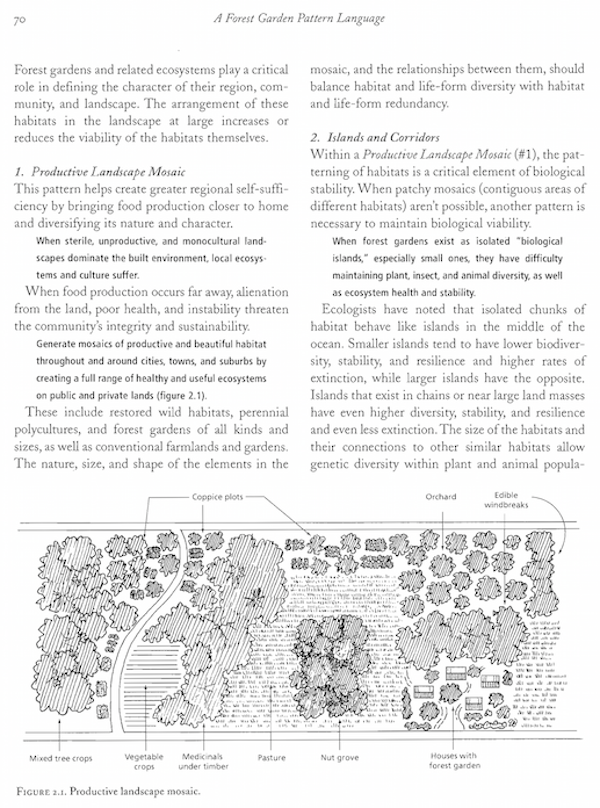

2. Edible Forest Gardens uses the pattern language pattern language concept developed by Christopher Alexander (NC 2013; 2015). Here is an example of this powerful method:

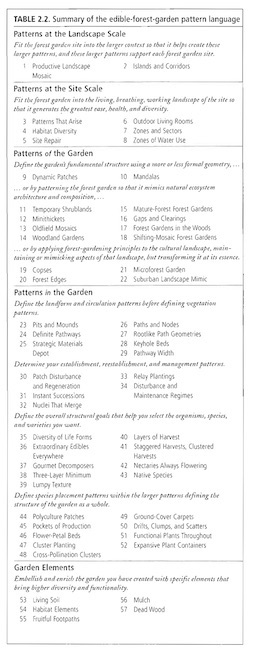

Pattern #1, “Productive Language Moasic,” is very, very far from the typical way gardens are organized into beds, with no thought of “balancing habitat and life-form diversity” (except, to be fair, as in the form of companino plants. Here is the complete list of patterns:

#42, “Nectaries Always Flowering” is particularly evocative. More sophisticated and less mechanistic than the seven-layer approach (which could be decomposed into these patterns, I am sure; I leave that as an exercise for the reader).

So, readers, if any of you are still in the planning phase for your garden, or are looking for a good project in the yard or property, this is a beautiful and very thought provoking book.

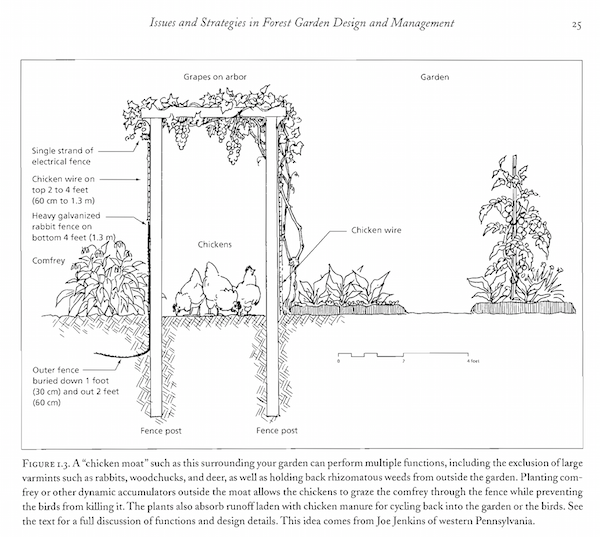

UPDATE Being pressed temporally, I forgot to add the “chicken moat”!

ZOMG, what a brilliant concept. Talk about stacking functions! Have any readers implemented something similar? Those of you with similar problems to solve — e.g., varmints — does this look like a good idea?

I love this idea, but from reading on their site it looks like their books would not be as helpful for my area, suburban Houston. Can anyone suggest a book that would work for that climate zone? Thanks!

Volume I has a chapter section on suburbs. I would be surprised if nobody has applied these principles to the suburbs.

A guy called Jake Mace the Vegan Athlete has a series of youtubes on how he transformed his Tempe AZ suburban yard into a food forest. The neighbouring ‘lawns’ are mainly gravel with a few cactus, as was his to begin. There was a marital breakup and last I heard he and his new lady were WOOFing in Spain. Haven’t followed up recently, but his old stuff should still be up on Y’tube.

I would think the design principles apply, but you need a different plant list – can’t help you with that.

The original Permaculture books, by IIRC, Mollison, are meant for Australia and consequently have long lists – one entire book – of tropical and subtropical, drought-resistant useful plants (the longest description of all is of that archetypal suburban plant, dandelions). The solar direction is opposite, so an intriguing lesson in geography.

Those books also have a LOT about fending off wildfire, so very apt for southern California.

Put all your energy and money into becoming a modern day nomad.

Urban Harvest has a lot of classes taught by experts in gardening in the challenging environment of Houston: https://www.urbanharvest.org/education/

And John Panzarella teaches grafting:

http://www.panzarellacitrus.com/aboutjohn

Thank you for all the suggestions!

And, for those of us in the great Southwest, here’s the go-to book, Eat Mesquite. Link:

https://www.chelseagreen.com/product/eat-mesquite-and-more/

Yours Truly is looking at the front yard mesquite tree with great anticipation. It’s my source of mesquite flour. Hoping for a bumper crop of mesquite beans, what with all the winter rain we’ve had.

Not quite growing a forest, but I’m just back from a forest walk with a friend with a bagful of wild garlic. She uses them for making egg and wild garlic dumplings, pesto, and salad. I’m lazy, I’ll just add them to a smoothie. Since I’m working from home I won’t have to be too concerned about anyone complaining about my garlic breathe….

Made wild garlic pesto yesterday. Picking more tomorrow. It is, to say the least, abundant here right now.

Not sure foraging counts as an essential reason to leave the house (UK) but fortunately we have a dog.

These and so many other wonderful books can be downloaded for free, or “borrowed”, probably copied, I’m tech ignorant of that:

This may not last forever, so build your library now if you don’t have the real thing on your shelves.

Here’s

A Pattern Language

https://www.greenbuildermedia.com/design/free-ebook-download-christopher-alexanders-classic-a-pattern-language

Here’s hundreds of gardening books:

https://archive.org/details/GardeningBooks/page/n9/mode/2up

Isaac Marsh, that brick building in your picture will absorb a lot of sunlight and radiate heat. It might be enough to grow citrus in England?

Don’t forget clear material to form a roof over the tops of your fence, a built in hothouse, even if open at one end, makes a huge difference in what you can grow.

A bar-owner here in Toronto has a ‘patio’ similar to that, long and narrow and buildings on either side. The place is full of espaliered fruit trees espaliered to the side walls, including a fig. Yeah, fig tree, outside, in Toronto.

Looking at the chicken moat. I’d take the rabbit fencing all the way to the top and maybe over. The raccoons here are very smart and they love chicken.

Kiwis are another large vine that needs an arbor. Besides the familiar fuzzy ones, there are hardier ones that are more like grapes. One is even variegated, so highly decorative.

However, in my experience, they seem incompatible with our clay soil.

Iowa Kiwi report: my wife has 3 on our former clothes line, and while they survive the winters and keep growing, the fruits have been tiny and shriveled.

She has espaliered apple trees on the back fence but no fruit there either. She’s adding a crab apple this year hoping it will help.

We placed a big order from Seed Savers Exchange yesterday. They are stating that they are in back order mode with no guarantee of delivery time.

Observe the strand of electric fence at top. I’d probably go for 3 but it should keep raccoons out until they bring up the bridging teams.

I’m in Montana, so cold winters and hot dry dry dry summers are my challenge. I’m in a town lot — 50 x 100 feet. Fifteen years of planting fruit bushes and trees (cherry, apple, plum, gooseberry, red and black currants, raspberry and grape — although I kill grape vines, we’ll see if the one I planted last summer lived), and building a big veg garden + chickens. Had to enclose the veg garden in cattle panel + chicken wire because you do NOT want fresh chicken shit in your food crops (also to keep the cat/dog out). I planted a lot of shrub roses on the outside of the veg fence because I like them, and they’re pretty. I can’t quite support myself out of the garden, but I come fairly close, especially if I’m good about blanching and freezing veg for winter. I blogged about it for ages at Livingsmallblog.com, although the last couple of years I’ve been working on a book project so blogging has fallen off. But feel free to go take a look!

With your grape vine, go old world. Cut it back and keep it low to the ground. Cover it with loose soil in the winter after pruning it way back. (Leave this year’s wood with two buds for next year’s fruit).

I’m sure he means well, but landscape fabric, especially the translucent spun kind, is work of the Devil. They’re not effective and roots will grow through them, and they are an absolute pain to get rid of. Newspaper, cardboard, or just a lot of weeding in year one are much better options for weed control.

I would recommend The Backyard Homestead as a starter guide. It’s not complete by any means, but covers a lot of topics very clearly, in a relatively small book. For advice on individual crops, Johnny’s Select Seeds and Southern Exposure Seed Exchange have great guidance on each vegetable.

Okay, not reading carefully. I guess he’ll get rid of the landscape fabric.

Thank you. I bought a house with landscape fabric, and as you describe it is a haven for weeds. I believe the landscape fabric manufacturers and weeds have some form of kickback deal….

I’ve been looking at permaculture for years now. One thing that becomes glaringly obvious when you put aside all the hype and pretty words is that there has never been anything like a rigorous study to see what the actual inputs / outputs are for permaculture. Let alone a comparison to other methods (not only monoculture)

Try reading through some forums where these discussions come up and you quickly will see the cult-like groupthink. This is yet another woo woo fantasy not grounded nor even informed by reality and scientific rigor. It’s all about the idea and the feelings behind it.

There is alot of useful stuff there, absolutely. But too many chug the koolaid and see this as some sort of cure for the world’s ills.

This sums it up pretty well:

https://medium.com/@spensergabin/getting-the-cult-out-of-permaculture-eb363230d72d

Getting sunlight to the vegetable plants I find is a challenge. I only have one tree left in my backyard, a locust- so it is dappled shade, but my neighbours have huge maples. Shade is great in the hot summers we have, but I’ve had to tuck my vegetables in wherever I can find a sunny spot.

I do have an Elderberry and a Serviceberry I also grow rhubarb and I made a raised bed in the middle of the lawn(in the sunny spot) that became a strawberry patch.

I think my point is that I can do a piecemeal sort of food forest depending on the available sun.

Integrated Forest Gardening by Weissman and The Vegetable Gardeners Guide to Permaculture by Shein. Are both useful. Thanks for posting about this and the PDF download. The book is a little pricey and I have not bought it yet. Maybe used…

Here are good resources for plants that you can create your forest garden with:

https://pfaf.org/user/Default.aspx

http://perennialvegetables.org/

In response to al apaka, I think Ernst Grotsch has demonstrated that nature will provide all the inputs you need even at the commercial scale: https://agendagotsch.com/en/

Well you have to put in human labor and the plants.

As well as the work of Singing Frogs, which is not really forest gardening as they mainly focused on and sell annual crops:

http://singingfrogsfarm.com/

For people interested in books about soil, here is a link to Acres USA bookstore about the soil-specific book titles collected together from their more general March Sale notice.

https://www.acresusa.com/collections/soils?utm_source=Acres+U.S.A.+Community&utm_campaign=0eab5d5094-HSS-3-20_Keynote-Announcement&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_65283346c2-0eab5d5094-184789077&goal=0_65283346c2-0eab5d5094-184789077&mc_cid=0eab5d5094&mc_eid=f874b279b6

I would most recommend those books which were written in German and have been translated into English for the first time. These books offer detailed soil information and knowledge which I have seen NOWHERE in ANY of the written-in-English soils literature. I would also recommend books by William Albrecht. I would recommend others but there is no space or time.

I had originally tried including this in a comment also about the Acres USA Soil Summit in California this summer. But this computer system destroyed that whole comment going between screens. So I have just written this mini-comment instead.