Yves here. Um, ya think what afflicts insects might affect humans too?

By Ellen Welti, Postdoctoral Researcher of Biology, University of Oklahoma. Originally published at The Conversation

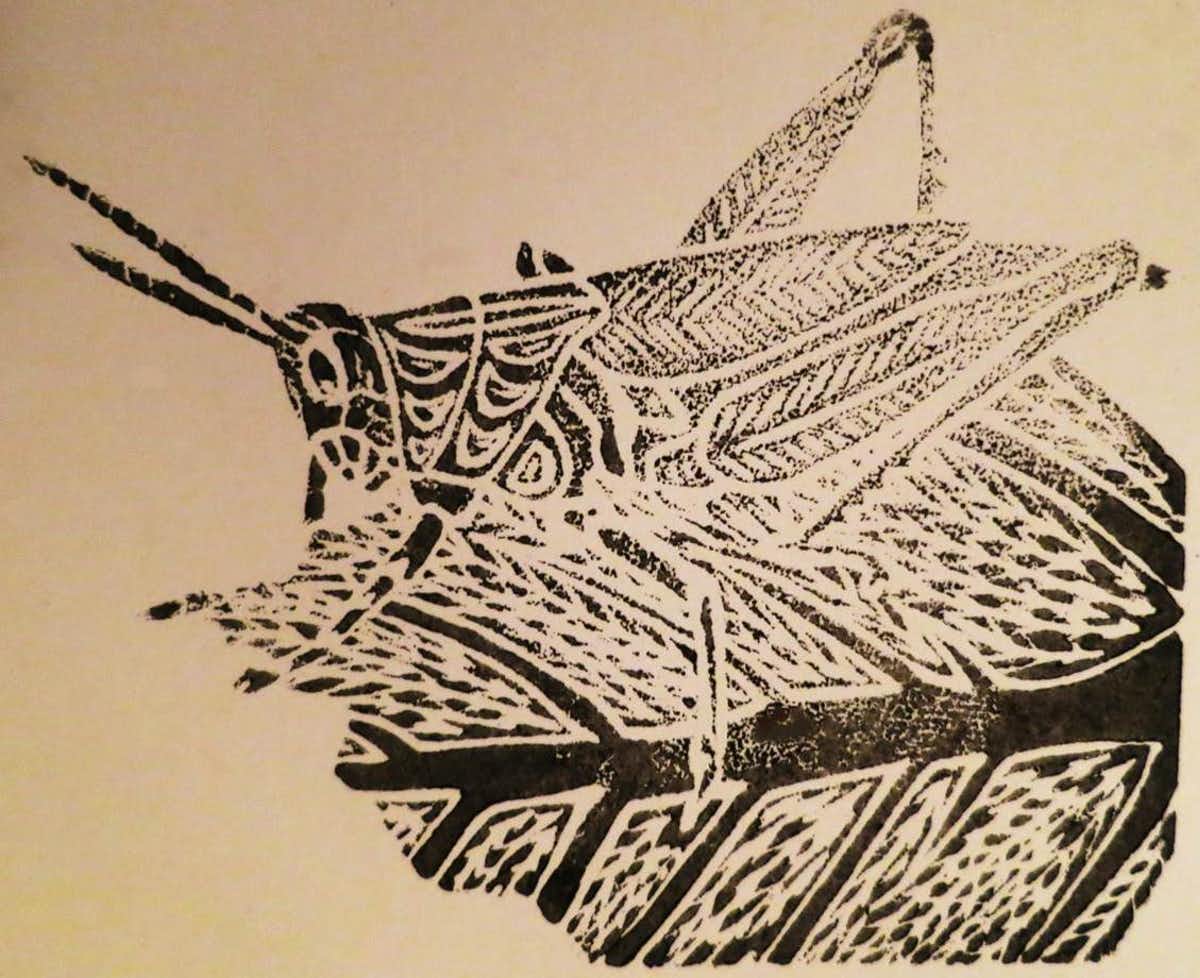

Grasshopper populations, like those of many other insects, are declining. My colleagues and I identified a new possible culprit: The plants grasshoppers rely on for food are becoming less nutritious due to increased levels of carbon dioxide in the air.

Ever-increasing levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere tend to promote plant growth by supplying them with extra carbon. But all that added carbon is squeezing out other nutrients that plant feeders – like insects and people – need to thrive. These fast-growing plants end up less dense in nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus and sodium – more like iceberg lettuce than kale.

On our study site in a Kansas prairie, my colleagues and I show that across more than 40 species of grasshoppers, total populations are falling at more than 2% a year. This led to an overall reduction in grasshopper numbers over the past two decades of about one-third. These population declines parallel the decline in grassland nutrients. Grasshopper populations vary year to year for many reasons, but my colleagues and I believe that the dilution of plant nutrients caused by elevated CO2 is the most likely reason for the decline.

It adds up to what we call the “nutrient dilution hypothesis”: Increased CO2 is making plants less nutritious per bite and insects are paying the price.

Why It Matters

Ecologists have thus far focused on pesticide use and the loss of native habitats as causes for insect declines.

These factors aren’t likely at the large native prairie reserve where I work. Yet the 2% per year decline in grasshoppers our study found is eerily similar to the 2% declines reported from long-term studies around the globe of moths and butterflies, whose young – caterpillars – are also voracious plant feeders.

Other factors, like pesticide use and habitat destruction, are certainly hurting insect populations in many places. But since CO2 is increasing globally, my colleagues and I suspect that nutrient dilution is likely bad news for plant-eating insects across a huge variety of habitats, in both pristine and degraded ecosystems. And since insects are crucial parts of all terrestrial food webs, their loss affects many other organisms from plants to birds.

How We Do Our Work

Konza Prairie is a large protected prairie in northeastern Kansas, and researchers have been collecting data on the grasses, insects, and animals there since the early 1980s. My colleagues and I relied on this long-term data and physical samples from years past to perform our study.

Grasshopper numbers fluctuate on a roughly five-year cycle that follows changes in the climate, like the El Niño Southern Oscillation. Having a decades-long data set allowed my colleagues and me to clearly separate these cycles from the long-term population decline and see how increasing CO2 levels played a part.

This kind of data is surprisingly rare, which has led to a good deal of controversy regarding the ubiquity of insect declines. Sites like the Konza Prairie (part of the NSF-funded Long-Term Ecological Research Network) are on the front lines in documenting Earth’s changing ecosystems.

What Still Isn’t Known?

Nutrient dilution by CO2 is a compelling hypothesis for why widespread insect declines are happening. Our data jibes with other experiments that pump CO2 into ecosystems and drive down both plant nutrients and insect growth.

But solid data on insect numbers over time is still quite rare, and there are still more questions than answers. How widespread is nutrient dilution in ecosystems worldwide? Are plant-feeding insects suffering the greatest declines? Which ecosystems will be hardest hit?

At present, we ecologists lack even basic population estimates for most of Earth’s invertebrate species, which comprise the vast majority of animal diversity.

I suspect that if nutrient dilution by CO2 is indeed widespread, it will likely be affecting Earth’s ecosystems and organisms – including humans – for generations to come, at least as long as fossil fuels burn and CO2 levels continue to rise.

“Carbon-hydrate” rich fast food!

Hello savvy gardeners, I’m going to plant some native Minnesotan flora in my garden this year instead of vegetables. How might the information in this article help me decide what to plant? I was going to do wildflowers for the bumblebees. Any advice?

This news which has been floating around for a while is very depressing. I guess I’d like to see the whole chemical reaction explained and modeled. Exactly how is the CO2 decreasing what has to be complex sugars. And is this true for all plants? The issue is that it is a great idea to plant native plants and maybe a few others specific for bees and butterflies. There are some very beautiful plants in a many non standard colors. The problem is, given this article is there doesn’t seem to be any easy way to make the plants more robust. This leads to all kinds to problems. But something is better than nothing so go for it.

General recommendations:

At this stage in the game, buy plants if possible. Many native plant seed require weeks or months of cold wet conditions (aka stratification) in order to germinate (and that window may have passed.) Be sure and check for information about germination requirements when buying seed packets.

Choose perennials over annuals if room is limited. Perennials, of course, won’t need to be replaced every year. Also, perennials are often preferred by bees due to greater amounts of nectar/pollen compared to annuals.

Plant “large” patches of plants that bloom throughout the season to provide sufficient resources to support a/some colonies of bees. Seem to remember a recommendation of 6′ sq. ft. There is also lots online about encouraging bees in your area. xerces.org is a good place to start for bee info.

I’m sure there is a lot of specific information online about prairie plants and gardens for MN. There is much to learn! Don’t be discouraged by initial setbacks or failures. I’m in year 6 with a native garden, and am still learning and trying to figure things out.

Perennials are certainly the first priority.

But annuals are good too, if you pick the right mix optimized for your zone (There are seed mixes that are good for beneficial insects where some bloom early, some late, so you get a seasonal cycle.) They also cover more ground for the buck than perennials.

Self-seeding annuals are nice because they provide instant gratification. The presence of beauty (as Pollan would agree, I think) is also an incentive to go into your garden. I’ve gotten enormous amounts of pleasure from a few pounds of wildflower mix, and the soil in which the perennials grow too is all the better for that.

Way to go ! Katy .. did ( sorry, I couldn’t help myself ..). Regardless of what you decide for the Bumbles .. save a plot or three for sustenance for yourself … in light of current or future events .. should Capt. Corona make it’s way near you. You never know when sand will gum up the supplychain, uh, gears ! Maybe a state university extention near you has a Michigan ‘Flora’, or some such, that you could access, to find plants that would suit your site. Good luck, and I’m sure the bees will be appreciative of whatever you introduce towards their sustenance.

Oh my goodness! Ellen and her mom are family friends. Feeling a strange sense of pride in something I had literally nothing to do with. But, go K-State and growing up in Manhattan, Kan. among a fantastic group of people!

> Ellen and her mom are family friends

The NC commentariat is the best commentariat.

My personal experience working with creating insect balance (and working with various other critters) comes from the Perelandra Gardening Workbook and other information they share. Machaelle Wright, the author, has been working in a conscious partnership with nature for >40 years. In her books she shares the insights she’s been taught over these many years, and the processes she and nature have developed together so that anyone who wants can have the same two-way conscious partnership with nature for their personal environment.

Every environment is different. What’s needed to restore balance to the insects on my property is not the same as what might be needed for my next door neighbor’s property.

There are many things that impact insect balance. It will be great when more scientists and non-scientists consider nature’s perspective and insight (and not just humans’ best guesses, no matter how well-intentioned).

When working with nature to restore balance to a given insect population, nature will suggest steps that take into account all the variables (including CO2 levels), even the variables that we humans have no idea about.

These processes are meant to be used on the land or property we individually own or rent, or with the owner’s agreement.

One of the things Machaelle Wright learned early on is that insects play an important role in communication with humans. Often, big changes in insect behavior is a big wake-up call that there are imbalances that need to be addressed.

> When working with nature to restore balance to a given insect population, nature will suggest steps that take into account all the variables (including CO2 levels), even the variables that we humans have no idea about.

That is very true. One of the things I have liked about gardening is that I discover I have done the right thing only after doing it. “You can observe a lot by just watching.”

If you ever read any of Wright’s books she describes the importance of observation. However this was most often used to help her understand *natures* understanding of balance or to demonstrate principles different from human approaches to attempt to create balance.

An active equal partnership with nature intelligences with conscious two-way communication is fundamentally different from benign observation and doing one’s best. If you ever read any of Wright’s books you’ll see what I mean. “Behaving as if the God In All Life Mattered” is another excellent starting point.

It would be interesting to know in painstaking detail ALL of the exACT mechanisms by which greater sky carbon is causing plants to dilute their mineral nutrients.

In the meantime, has anyone suggested setting aside just enough of the Konza Prairie to be a statistically meaningful area of insect-hosing land . . . and applying year-in and year-out to that set-aside study-area a small-but-real amount of flour-fine multi-mineral-mixed rock dust to it at whatever time of year is best? To see if offering the system a dose of micronized multimineral rock dust flour offers minerals easier-to-uptake and hence allows the greater growth to be just as nutramineralized as before? The answer would be interesting either way.

I don’t know about ALL of the mechanisms, but I know that a dominant one the effect of greater CO2 concentrations on plant “transpiration” (i.e., the release of water to the atmosphere during absorption of CO2): https://phys.org/news/2011-03-co2-atmosphere.html.

In short, plants now release less water when absorbing a given amount of CO2. And because they release less water into the air, they absorb less water from the ground. [This is a simple matter of conservation of mass.] And because they absorb less water from the ground, they absorb less of the minerals that are dissolved in that water.

Could we compensate with mineral fertilization? Perhaps. But groundwater can only hold a finite amount of dissolved mineral content. If it’s already close to saturation, any added minerals will precipitate out and remain in the ground.

You raise what could be a real problem. I don’t know enough to know if it is. The experiment I suggest would help us find out whether that problem poses an inherent ceiling to our ability to raise the nutrition-load of perennial prairie plants with rock dust applications. We won’t know if we don’t do the experiment.

Now . . . since the nutrition-dilution problem has also been referenced for domestic edible crop plants, I think there are already highly diffuse and hard-to-gather-into-one-place datasets on the mineral nutri-loads of plants on NON-depleting soils under the impact of rising skycarbon levels. In corn, for example, ” test weight” is supposed to be a fellow-traveling indicator of “mineral nutri-load” and to a lesser extent “protein load” in a sample of corn. Have the test-weights of corn been holding steady or going down over the last few decades? And are eco-literate organic growers

getting higher test-weight corn even in the teeth of rising skycarbon?

This link tries to link corn test-weight to percent kernel drydown. And that can often figure in.

But the percent of kernel moisture can be measured, and different corn samples can be dried down to the same moisture percent as eachother, and THEN their test weights compared. ( I sure HOPE someone has been gathering those parTICular data).

https://fyi.extension.wisc.edu/grain/files/2009/12/CornTW09.pdf

Here is a different corn test weight little webicle ( ” web article”). The search-engine blurb claims it says in part that the “standard” test-weight for a bushel of corn “should be” 56 pounds per bushel.

I have read of eco-literate growers achieving higher test-weights and getting higher prices. Have THOSE growers been seeing their test weights go down as skycarbon levels go up?

https://fyi.extension.wisc.edu/grain/files/2009/12/CornTW09.pdf

Well, the computer kept failing and failing to copy-paste the link to the second article. Now I can’t find it. So I give up on that.

The question of whether eco-literate farmers are getting their corn at a set percent moisture content to weigh more than other farmers’ corn at that same set percent moisture content. If they are, it shows they know something about getting ” more nutrition per corn”. Now . . . are THOSE farmers getting lighter more nutri-poor corn as skycarbon levels rise?

> But solid data on insect numbers over time is still quite rare, and there are still more questions than answers. How widespread is nutrient dilution in ecosystems worldwide? Are plant-feeding insects suffering the greatest declines? Which ecosystems will be hardest hit?

> At present, we ecologists lack even basic population estimates for most of Earth’s invertebrate species, which comprise the vast majority of animal diversity.

This would be a job for citizen science, funded by a Jobs Guarantee.

Why not focus instead on what is really killing the insects…INSECTICIDES!

And why not also focus on GLYPHOSATE, GLUFOSINATE and the myriad of other chemicals used by big agriculture and produced by big pharma! These things we can control, Co2…not so much.

Rising piles of evidence and experience indicate that ecologically-literate approaches to organic agriculture tend to net-net suck down skycarbon and bio-sequester some of it into the soil for longish-term storage. And organic agriculture of course involves the non-use of persistent synthetic insecticides as well as the non-use of glyphosate, glufosinate and some of the myriad of other chemicals.

So growing the customer base for eco-literate organic food and shrinking the customer base for toxic-chemical food will have the double effect of reducing these insect-suppressor chemicals AND draining down some of the skycarbon at the same time.

We have the scientific and technological knowledge to be able to lead the CO2 around by the nose to some extent. What we don’t have is political power over and against the carbon mass skydumpers. Getting that political power would require winning a Civil Culture War.