Lambert here: Nice to have a natural experiment concerning the “Why don’t they just move?” argument beloved among liberal Democrat meritocrats.

By Sebastian Heise, Economist, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and Tommaso Porzio, Assistant Professor of Economics, Columbia Business School. Originally published at VoxEU.

Thirty years after reunification, a stark and persistent wage gap between East Germany and West Germany remains. This column studies why East Germans do not migrate to the West to take advantage of the higher real wages there. Analysing data from more than 1 million establishments and almost 2 million individuals over 25 years, it suggests that moving people across space is difficult and costly. Reallocating workers to better jobs at their current location could be a more cost-effective avenue to increase aggregate wages, and even accelerate regional convergence.

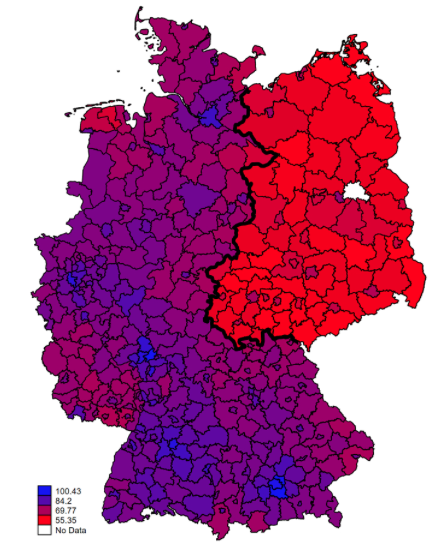

Thirty years have passed since German reunification. Workers anywhere in Germany speak the same language, face the same legal system, and are free to accept jobs anywhere in the country. Nevertheless, a stark and persistent wage gap remains between East Germany (the former German Democratic Republic) and West Germany. Figure 1 plots the average wage, adjusted for cost of living differences, in each county in Germany. A 26% real wage gap persists between the two regions.

Figure 1 Average Wage in Germany by County

Notes: Average daily wages obtained from a 50% random sample of establishments via the Establishment History Panel (BHP) of the Institute for Employment Research (IAB). Real wages are expressed in 2007 euros valued in Bonn, the former capital of West Germany, using county-specific prices. East–West border is drawn for clarification; there is no border today.

This persistent divide is puzzling because economic theory would predict that East German workers would migrate to the West until wages are equalised in the two regions. However, Germany is not unique in its experience of significant regional inequalities: wage differences across regions are present in many countries (Moretti 2011, Gollin et al. 2014). Understanding the sources of these wage gaps is crucial to inform labour market policy. Should governments try to encourage migration from low- to high-wage regions?

In a recent working paper (Heise and Porzio 2019), we study why East Germans do not migrate to the West to take advantage of the higher real wages there. We track up to 25 years data on more than 1 million establishments and almost 2 million individuals to obtain a detailed picture of their employment histories. When the data are not sufficient to provide an answer, we turn to economic theory.

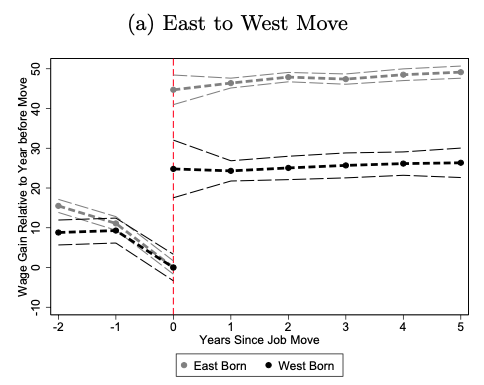

We find that observable differences in workers’ demographics or industry composition do not explain the wage gap. Instead, we find that 60% of the gap is accounted for by establishment characteristics: establishments in the West pay a given worker a significantly higher real wage. To illustrate this point, Figure 2 shows how the wages of a typical East-born worker and a typical West-born worker change upon a move from East to West Germany (panel a) and from West to East (panel b). We find that the real wage of an East-born worker increases by a staggering 40% when moving to the West. Moreover, we document that East-born workers obtain significantly higher wage gains when moving to the West than West-born ones, and vice versa, suggesting that workers need to be compensated in order to leave their home region.

Figure 2 Changes in Wages of TTypical East-born and West-born Worker upon Moving across former East–West German Border

Notes: The figures plot the point estimates of wage changes from an event study of a migration move across the former East–West border, where the wage change is computed relative to the year of the move. East German workers are in grey, West Germans in black. The dotted lines represent the 95% confidence intervals.

Source: Linked Employer–Employee Data (LIAB).

Why Don’t All East-Born Workers Move to the West?

It would be tempting to conclude that large moving costs must be preventing migration. However, this argument is flawed because cross-regional movers are special in two ways: they must have received a job offer to move, and they must have decided to accept this job opportunity.

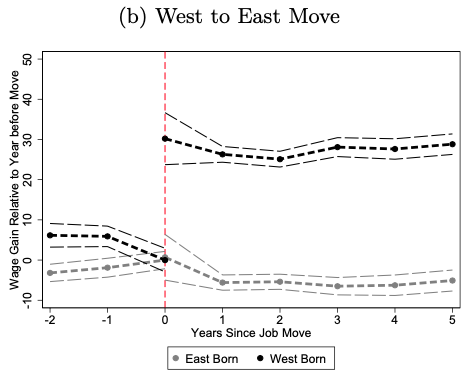

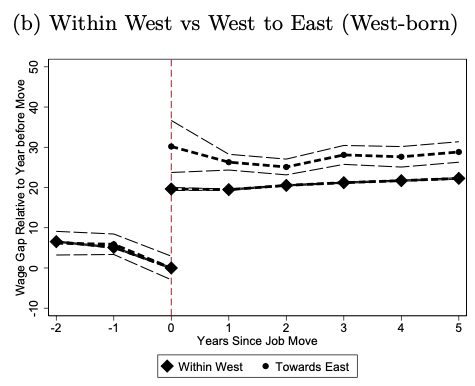

Figure 3 compares the wage gains of East-born workers moving to the West to their wage gains when switching jobs within the East (panel a), and similarly for West-born workers (panel b). Workers obtain substantial wage gains even when switching jobs within their region, and hence not all of the wage gains when moving across regions are due to the spatial component of the move.

Figure 3 Wage gains of East-born and West-born workers switching jobs within their region versus across the former East–West border

Notes: The figures compare the wage changes of a move across the former East–West border (dashed lines) to the wage changes from a job switch within region (solid lines).

Source: Linked Employer–Employee Data (LIAB).

Workers are in fact remarkably mobile between East and West Germany: about one-third of workers born in the East have at some point been employed in the West. However, we find that workers have a high likelihood of returning to their home region.

Consider an East German worker currently employed in the West German city of Frankfurt who considers switching jobs. We find that the worker is about twice as likely to move to the city of Leipzig in her home region of East Germany than to Munich in the West, even after we control for the amenities of Munich and Leipzig and despite both cities being the same distance away from Frankfurt.

To fully account for workers’ selection and to unpack the spatial barriers into its components, we develop a model of worker reallocation across firms and across regions. Our estimated model shows that the moving costs faced by workers are relatively modest, equal to roughly 4% of lifetime income. This figure is significantly smaller than estimated in the previous literature (Kennan and Walker 2011).

Instead, we estimate that workers have a strong attachment to their birth region. An East-born worker is indifferent between €1 earned in the West and 95 cents earned in the East. Furthermore, we find that workers only rarely receive opportunities to move across regions: a typical East-born worker receives 20 times more job offers from the East than from the West. Finally, we estimate that individual skills are perfectly transferable across regions.

How Did We Reach These Results?

Our model infers them from data on wages and workers’ job-to-job flows both within and across regions. For example, we estimate workers’ strong home attachment from the relative wage increases when moving across regions (see Figure 2). East-born workers receive significantly higher wage increases when moving East to West than West-born workers, even though both types of workers face the same distribution of job opportunities. Our model justifies this behaviour with a strong home bias: East-born individuals need extra compensation to leave their home region.

Policy Implications

We simulate two alternative policies in our estimated model. First, we show that subsidising workers’ migration costs does not, in fact, improve aggregate welfare. While average GDP and wages rise slightly, these gains are completely offset by workers’ disutility of living away from their home region. Simply put, East German workers get higher wages when we subsidise their move to the West, but they are less happy.

We compare this result with an equally costly policy that subsidises firms’ hiring costs to make it easier for workers to match with a good job where they are. While this alternative policy delivers just slightly lower average wage and GDP gains, it generates significantly larger welfare gains for the average worker, who does not need to relocate to obtain a higher wage. Thus, policies that improve local labour markets can be more cost-effective than equally costly policies that promote migration to better-paying regions.

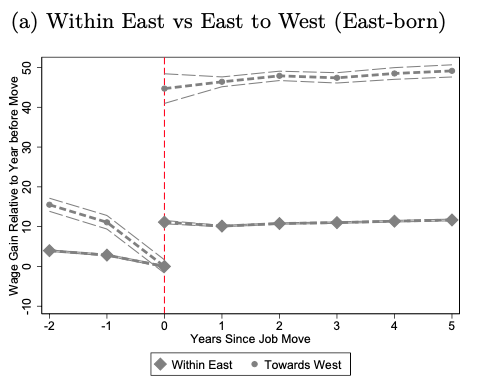

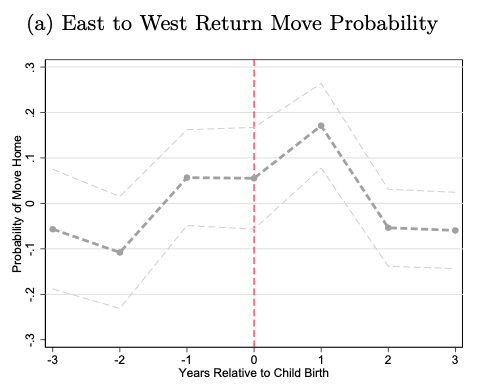

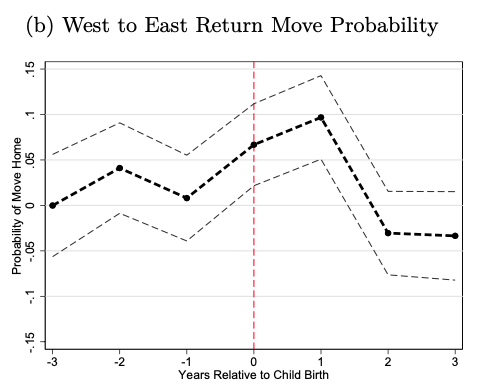

A key factor explaining our results is the workers’ attachment to their region of birth. We provide some evidence on its potential sources. Figure 4 analyses the likelihood that workers currently outside of their birth region return ‘home’ after they become parents. We find a significant increase in that likelihood, possibly because workers seek family support.

We also show that workers’ attachment to their home is not specific to the East and West regions, but also holds at the state level. For example, workers born in Bavaria would rather live in Hesse (in the West) than in Saxony (in the East), but still firmly prefer Bavaria overall. This result shows that the home bias is a general phenomenon, not specific to the East–West separation.

Figure 4 Likelihood that workers living outside of birth region return ‘home’ after they become parents

Notes: The top panel shows the probability, around the event of the birth of a child (t=0), that an East-born worker that previously migrated to the West returns back to the East. The bottom panel shows the same for a West-born worker.

Source: German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP).

Was German Reunification an Economic Failure?

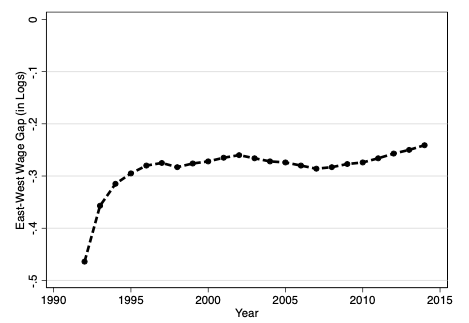

Despite the significant wage gap between East and West Germany today, the gap is much smaller than it used to be. Dauth et al. (2020) study the process of reunification and document large initial wage improvements in the East. Figure 5 shows the wage gap between East and West Germany over time: as is well known, East German wages rose steeply in the first years after reunification, but then convergence essentially stopped.

Figure 5 Wage gap between East and West Germany, 1992–2014

Notes: The figure plots the wage gap (in log points) between East and West Germany over time from the first year from which data is available, 1992, to the last one, 2014. It shows that East wages caught up quickly in the first few years, after which convergence essentially stopped.

Source: Establishment History Panel (BHP).

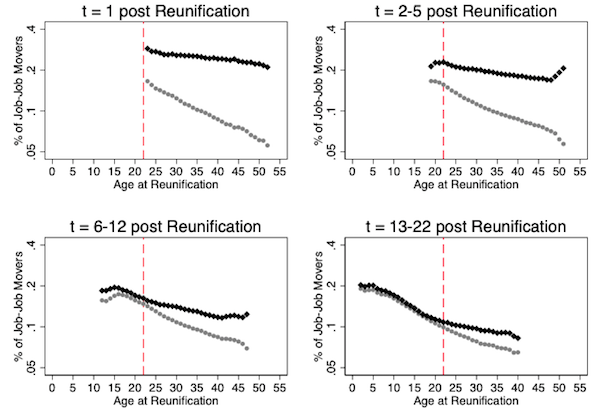

Dauth et al. find that the initial wage convergence was not mainly driven by migration from East to West, but instead by the reallocation of labour within East Germany. Older birth cohorts, which were most exposed to the static labour market in the German Democratic Republic, were the most likely to switch jobs across firms within East Germany (Figure 6). This reallocation of labour within the East German labour market delivered significant aggregate wage gains.

Figure 6 Age at reunification and share of East-/West-born workers that change jobs between two years, 1992, 1993–1996, 1997–2003 and 2004–2013

Notes: Black: East-born workers; grey: West-born workers. For each cohort and each time period, and separately for East- and West-born individuals, we compute the share of workers that make a job-job move between two years. The top-left graph plots these computed probabilities as a function of age at reunification, for the first year for which we have data right after the reunification, 1992. The East-born workers, in black, are more likely to change firms. The differences between East- and West-born are more pronounced for relatively old individuals. The top-right graph plots the same probabilities averaged across the period 1993–1996. The bottom-left covers the period 1997–2003. The bottom-right the period 2004–2013. The young cohorts that enter the labour market after reunification behave the same, irrespective of their birthplace. Instead, the cohorts exposed to the German Democratic Republic labour market are more likely to change employer even 20 years after reunification.

Source: Universe of employees subject to social security from the IAB Employee History File.

Our work thus points to the following conclusion: moving people across space is difficult and costly. Reallocating workers to better jobs at their current location could be a more cost-effective avenue to increase aggregate wages, and even accelerate regional convergence.

Authors’ note: The views and opinions expressed in this column do not necessarily represent the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. This study uses the weekly anonymous Establishment History Panel (Years 1975 – 2014) and the Linked Employer-Employee Data (LIAB) Longitudinal Model 1993-2014 (LIAB LM 9314). Data access was provided via onsite use at the Research Data Centre (FDZ) of the German Federal Employment Agency (BA) at the Institute for Employment Research (IAB) and remote data access. The study also uses data made available by the German Socio-Economic Panel Study at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), Berlin. Neither the original collectors of the data nor the archive bears any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here.

Home has a value.

The second chapter of “Good Economics for Hard Times” covers the topic of why migration occurs and why it does not occur. It is complex, but “Home has a value” is part of it.

https://www.amazon.com/Good-Economics-Times-Abhijit-Banerjee/dp/1610399501

There are so many disincentives for migration that generally people need to be virtually driven out of their homes or provided a great deal of information and support to make the move. The US policies that assume the US is a magnet do not understand what is actually going on. Generally, people have to get to a point of desperation before they make the move unless they have enough knowledge and resources at the destination to inform them it would be a good move.

This makes sense. People are social creatures. They like to have social and cultural ties to the place where they live. Most people don’t want to uproot themselves from a place that has meaning for them. People should not be treated like atomised units in a labour market. The national government should create jobs where people are, instead of expecting people to move.

Yes but this article while bursting with data is thin on relevant detail. How do they define “strong attachment”? Of course everybody wants to believe that there’s no place like Heimat and many of us treasure our hometown experience. And how do they derive the numbers for likelihood to move from the relatively big data that they used?

The DDR was a dictatorship. Brothers and sisters ratted on each other, 1 third of the population was coopted by the Stasi. Even the real benefits of socialism like accessible childcare, education and health care were too often tainted.

The authors are selling fusion research but it tastes like economic modelling without the special sauce.

Ah, I’d like to see job by job comparisons, like mds, engineers, factory workers, construction workers, etc.,. Also training and educational opportunities. Contrary to what the article implies, there are in fact different levels of minimum wages in Germany as well as regulations. This is by design. Working at Siemens as president of Siemens medical, I was encouraged to think of the “East” as the US “South”. Meaning to Southern Germans, poor & stupid. (I don’t make the news I’m just reporting it). There are also tax incentives for corporations in Germany to build factories in the “East”. But I have to say, that the people of the Northern, Southern, and Eastern areas of Germany really do not like each other. As in really do not. Siemens is in the south, where the people are wonderfully friendly just as long as your not from the North and worse the East. Stories I could tell.

A couple of things:

1. Employers prefer to hire someone who does not need to relocate (the person already close can start working relatively quickly but the ones who has to relocate…)-> Recruitment from afar is done when skills cannot be found locally

2. Moving to find a job is slightly tricky as landlords prefers tenants who have jobs -> Moving in the hope of finding a job often means finding shared accomodation from far away and even then the ones who are looking for someone to share with prefers people with jobs. Younger people might be more willing to share accomodation

3. Moving production (or whatever is meant by:Reallocating workers to better jobs at their current location) to the east of Germany is easier than moving the production to a country where wages are even lower (Poland, Czech republic, Slovakia etc) but if the wage differential gets too high then the production might end up abroad -> Bargaining power of the workers is reduced.

& yes, people often return home to their home region after some time.

Might also be rephrased to be: Some people move away and endure some hardship while building up capital (savings) which they can bring back home where the savings have better purchasing power. The plan was not to move permanently, the plan was to earn and save enough money to buy a house (as an example) back home and then move home. Hopefully the people writing the report have encountered that kind of migrants.

My personal opinion about the ‘encouraging people to move’ is that it does increase property prices and rents in the areas where people are encouraged to move. It does also push wages down in those same areas. All of the above leads to increase of unearned income, some economists who promote meritocracy would say that policies increasing unearned income are bad policies…. Cynics would say that those same policies wins votes….

+1

Maybe the East Germans won’t move because they’re racist and West Germany is more diverse? /s

More seriously, how anyone could look at the outrageous ratio of cost of living:material quality of life in the big “blue” metros of the US, not to mention the housing shortages, and think, millions of people should move there!

Housing cost in big metro areas is definitely a big factor in Germany as well.

My cousin and her partner are both engineers – she’s a mechanical engineer and he is a civil engineer. Both in good, stable jobs that pay well by German standards. Both work in the Hamburg metro area, but they live well over an hour outside (which is a long commute by German standard) as that was the only way they could afford a place of their own without being completely house poor.

When people are very mobile, or are driven to be very mobile, it is hard to develop community. Community is anti-capitalist, when you have a functioning community more goods and services are exchanged in a barter system or at minimal cost. When you uproot everyone then you create a strong capitalist consumer culture where you have to purchase everything at whatever cost the market will bear.

Having a baby pushes many people back “home” because community becomes a priceless commodity at this point.

It is no mere coincidence that as people are herded into more congested urban spaces housing becomes more and more expensive and the rentier class becomes wealthier.

It has the added benefit of making the land you migrate from available to the same rentier class for a pittance.

What is not to like? for the 1%?

Mostly posting to amplify what peon wrote. Community and family ties are definitely economic benefits, often way beyond more money. We see that in rural US where extended families are more prevalent than in cities (in my experience, anyway) and they take of each other, especially with children and elders. Many people stay who could make a lot more money elsewhere.

As a German – although I’ve lived in the UK and US for the last 20 years – there are a couple of semi-obvious omissions in that report, at least from my perspective:

* The cost of living in the East is still substantially lower than in the West, especially when it comes to housing costs. The cost difference is high enough that my aunt and my mom (who are both in their 70s and on fixed incomes) were actually seriously considering to move to a rural-ish area in East Germany.

I think just looking at the wage difference leaves other important factors of the equation.

* Germany – at least back when I lived there – used to be a country of mostly renters, but the rental contracts tend to be longer term than we’re used to in the Anglosphere. Back when I lived there, it wasn’t unusual for a more settled person or family to have 5 year+ rental contracts that weren’t that easy to get out of.

* A lot of employment contracts have 3-6 months notice periods to the end of the quarter, at least if you’re in a regular job and not a 400 Euro “mini-job”. Of course that’s different if you’re a contract worker instead of an employee, but even as a contract worker, people tend to be multi-month contracts that one can’t just walk away from. Especially as a new employer will want to see a written reference from the previous employer. Not to mention that then you are on 3-6 months probation with the new employer, so unless your skills are very much in demand in your new location, it’s a pretty high risk proposition to move.

Again, please note that my information is somewhat out of date – since I left, Germany has been playing catchup on the neoliberal austerity train of thought, so both some of the social system and some of the protections for employees have been eroded. Either way, one has to look at the bigger social and political picture on this topic.

Thanks for the added detail.

Translation of article: There’s no place like home.

All this begs the question why firms would not have long since set up shop in the east on the basis of labor arbitrage? The skill sets appear to be the same. Transportation infrastructure? Distance to markets? Raw materials? What?

Partially because the ones who are big enough to do so kept going through East Germany and ended up places with even lower labour rates

Answer: because of the EU.

However cheap E. Germany may be, Bulgaria’s even cheaper.

As a Bulgarian, yes, Bulgaria is cheaper. Yet Germany does not set up factories there. In recent months Bulgaria and Turkey fought it out for a Volkswagen factory, Turkey won. Why? Brain drain and able body drain. Bulgaria is the fastest shrinking population in the world, so who would actually invest in that. I suspect East Germany suffers from much the same factors, albeit not to the same extent

Or try another view.

You are a business in West Germany. You try to attract qualified workers at the lowest possible wage. Certainly, there should be a pool of such workers in East Germany that you could recruit, that potentially could be eager to move to the west in search of wages that are still higher than in the East.

Or: you could just recruit workers from Turkey, who are even poorer and even more motivated to take relatively lower wages: and depending on circumstance, possibly able to be treated like indentured serfs with fewer rights.

Possibly the reason that East German workers aren’t moving in large numbers to West Germany, is because the labor market there is already saturated with low-wage immigrants. Remember: in the United States after the civil war, southern blacks did not move north in search of industrial jobs, because these jobs were all taken by refugees from (at the time) third-world Europe. It was only after mass immigration stopped, that southern blacks started to migrate north in search of better jobs – because it was only then that northern industries really needed their labor.

Let Germany radically reduce immigration, and create a genuinely tight labor market, and western industries will be desperate for eastern workers and offer large bonuses etc. But right now, there is no need, is there?

Just a thought.

In related “news” rich people don’t move because of taxes:

https://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=27987

All of which is to say that “homo economicus” does not, and never did, exist

So it took some modest researchers in Germany, without the rabid “free market” bias, to do something this clear. It blows away all the propaganda for being free to find your own way, to move to a better job market, buy a house with a picket fence. This research is a stealth bomb. Even if it does have such meticulous graphs that nobody will actually look at them. This could go over the heads of most of us Americans who are so mobile we never really stop to enjoy the moment. Those German phrases like enjoying “the everyday sweetness of life” are pretty lost on us. And god forbid that this research ever gets traction and somebody says, But I don’t wanna move anywhere – because then the proposal will have to be what these guys discovered – it’s better to earn-in-place. For everyone except the neoliberal masters of the universe, that is.

– it’s better to earn-in-place. StO

And the ultimate of that is not a Job Guarantee but a Citizen’s Dividend to replace all fiat creation beyond that created by deficit spending for the general welfare.

That and land reform so that every citizen has some land to work and work on (cf. Leviticus 25), not to mention live on.

To me, this is another of those “I’m glad somebody finally did some research on this so I can point to it in conversations” and “Well, no sh*t, Sherlock” kind of papers.

I mean, it just seems so obvious to me that the vast majority of people want to stay close their family and existing social networks, and that marginal, or even sizeable, economic gains would have difficulty overriding that, that it’s kind of crazy it even needs to be formalized like this. Shows to go you how out-of-touch with reality the mainstream of economics is, that the standard theory has so many problems predicting how people actually behave, in real-life situations.

I have read that ‘Ossies’ [East Germans] are regarded as being not as motivated and productive as other Germans.

I don’t know if that was true, or is true.

That certainly was considered true at least in certain places, not sure if this is still the case. There used to be this old joke in the GDR on how the socialist economy worked – “they pretend to pay us, we pretend to work” (basically because the money didn’t buy you anything).

What a lot of people forgot was how hard you had to hustle to make your life a bit better. Acquaintances from the former GDR would explain to me that whenever they saw a line at a shop, they’d join the line and basically buy what was available, so they could trade it to other people if they didn’t it whatever it was themselves.

The East German industry wasn’t that productive by Western standards, but you had to work pretty hard at having a half decent standard of living.

The joke I heard was, “The Soviets achieved the impossible: they made Germans lazy”.

Kevin, In reality no, but by perception absolutely. In the German version of the universe one finds all the money is in the south. Southerners attribute this to their very keen sense of hard work and enjoyment of life. The north is full of pushy Prussians and the East might as well be the Soviet Union, just an awful place – to this very day.

Titus,

How does the North-South divide in Germany map with the historically Protestant-Catholic divide?

Also, was what became East Germany ever as industrialized as what became West Germany? Was East Germany more severely affected by the truncation of Germany from what had been its easternmost regions (which are now mostly in Poland and reached even to the Russian enclave at Kaliningrad)?

I have wondered if the current configuration of German speakers in nations couldn’t have turned out differently, for example one Protestant North German hoch Deutsch nation and one Catholic Austro-Bavarian one.

This persistent divide is puzzling because economic theory would predict that East German workers would migrate to the West until wages are equalized in the two regions.

Differences in culture, family relationships and cost of housing all contribute.

I read something a while ago, it said women have moved west, to the point that it’s affecting marriage and birth rates. The ones left are those who aren’t educated or have the habits to do white collar work.

Just like old Irish and Italian neighborhoods in NYC. Those that could have moved away, all that’s left are the guys that want to be in Mob

From what I hear from a cousin, family lived up by the Baltic coast, the young people move west, the elderly are gentrified out of a 50Km ocean front belt.

This fits with a study of people moving to Montana, back in the late 90s/early 00s, that found a majority of people moving in within any given time period were actually moving back home, and not technically new arrivals.

Before 1945, I suspect wages in west Germany were higher than in the east. Prussian laborers and industrial workers generally had worse conditions and fewer freedoms than their counterparts in the Rhineland. Prussia came late to western civilization and remained a frontier land until the 1600s, and from about 1700 (when it became an important country) onward it always was a highly militarized and stratified area.

An interesting factor may be the cultural drift from nearly two generations living under such radically different political regimes. Personal morality, sexual mores must have diverged a lot in the different educational systems leading to deep-rooted discomfort in at least some of the easterners. Some people are more adaptive than others.OK then we could just call it love for “heimat” in general.

The fact that human beings are not prepared to give up family and social ties for money would seem to be the not-surprising finding of this study. It’s too bad we needed on of the posters–often more perceptive than the OP authors here–to point out that the COL is much higher in the West. . .