Yves here. It would be welcome, and overdue, if COVID-19 were to wreak as much havoc with the “markets uber alles” as it has with with people’s lives. But if the elites can patch things together so as to suit them, we may instead see an even nastier version of the counter-revolution. Crises tend to favor strongmen over collective action.

By Samuel Bowles, Research Professor and Director of the Behavioral Sciences Program, Santa Fe Institute, and Wendy Carlin, Professor of Economics, UCL; CEPR Research Fellow. Originally published at VoxEU

Like the Great Depression and WWII, the COVID-19 pandemic (along with climate change) will alter how we think about the economy and public policy, not only in seminars and policy think tanks, but also in the everyday vernacular by which people talk about their livelihoods and futures. It will likely prompt a leftward shift on the government-versus-markets continuum of policy alternatives. But more important, it may overturn that anachronistic one-dimensional menu by including approaches drawing on social values going beyond compliance and material gain.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a blow to self-interest as a value orientation and laissez-faire as a policy paradigm, both already reeling amid mounting public concerns about climate change. Will the pandemic change our economic narrative, expressing new everyday understandings of how the economy works and how it should work?

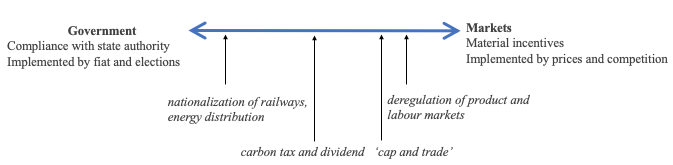

We think so. But it will not be simply a lurch to the left on the now anachronistic one-dimensional markets-versus-government continuum shown in Figure 1. A position along the blue line represents a mix of public policies – nationalisation of the railways, for example, towards the left; deregulation of labour markets, for example, towards the right.

Figure 1 The government–market continuum for policy and economic discourse

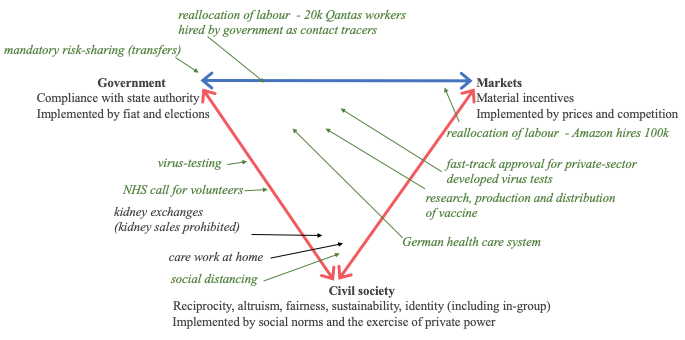

COVID-19, for better or worse, brings into focus a third pole in the debate: call it community or civil society. In the absence of this third pole, the conventional language of economics and public policy misses the contribution of social norms and of institutions that are neither governments nor markets – like families, relationships within firms, and community organisations.

There are precedents for the scale of changes that we anticipate. The Great Depression and WWII changed the way we talked about the economy: left to its own devices it would wreak havoc on people’s lives (massive unemployment), “heedless self-interest [is] bad economics” (FDR),1 and governments can effectively pursue the public good (defeat fascism, provide economic security). As the memories of that era faded along with the social solidarity and confidence in collective action that it had fostered, another vernacular took over: “there is no such thing as society” (Thatcher)2 – you get what you pay for, government is just another special interest group.

Another opportunity for a long-needed fundamental shift in the economic vernacular is now unfolding. COVID-19, along with climate change, could be the equivalent of the Great Depression and WWII in forcing a sea change in economic thinking and policy.

And the battle for the COVID-19 narrative is already underway. The Economist sounded the alarm: “Big government is needed to fight the pandemic. What matters is how it shrinks back again afterwards. … A pandemic government is not fit for everyday life.”3 Government overreach, we hear, led to America being unprepared. “Stringent and time-consuming FDA requirements are preventing academic and clinical labs around the country, with capacity and willingness to develop and deploy testing within their communities, from being able to do so.”4

But many Americans, Britons, Italians, Japanese and others probably wish that their governments, like South Korea’s, had done more not less at the outset, and that their fellow citizens had the civic mindedness that made the South Korean government’s policies so effective.

South Korea will be a major theatre in the battle for the COVID-19 narrative. We will hear a lot about how their success in containing the pandemic was due to their long experience with SARS, H1N1, and other epidemics in the region. Or is it the history of authoritarianism in South Korea’s politics? Or that South Koreans are, well, just more cooperative than, say, Americans?

We are not convinced. According to the authoritative Polity IV data set, South Korea is as democratic as the UK or the US.5 The US has had ample experience with epidemics. A never-released government report half a year ago simulated a hypothetical pandemic almost exactly anticipating what is now unfolding. Residents of Seoul are not, in fact, distinctive in their cooperativeness, at least not compared with people from Bonn, Boston, Zurich or Copenhagen in experiments about contributions to public goods (Herrmann et al. 2008).

Yet others will point to the immediate and massive testing, tracing and social distancing (all for the most part voluntary) that the South Koreans adopted, their quick mobilisation of expertise bearing on the outbreak, the extraordinary number of intensive care unit beds that were available, and their comprehensive health care system that facilitated and reduced resistance to these measures. South Korea has avoided extreme personal travel or movement restrictions and closure of airports.

But the struggle for the COVID-19 narrative need not rehearse the “more government versus more market” battle lines. Three snapshots of the unfolding pandemic explain why.

- In the UK, the National Health Service asked on 24 March for 250,000 volunteers to assist them. Recruitment to the scheme was temporarily halted five days later so that the initial 750,000 applications could be processed.6

- As of 9 April, 494,711 South Koreans have been tested for the virus, a level of participation that would have been impossible to enforce on a recalcitrant citizenry by governmental fiat.7

- Attacks on people of Asian descent are mounting around the world, encouraged, some think, by President Trump’s continued reference to the “Chinese virus.”

The COVID-19 narrative that emerges in the aftermath of the pandemic will have to embrace three truths. First, there is no way that government – however well organised and professional – can address challenges like this pandemic without a civic-minded citizenry that trusts the public health advice of its government and is committed to the rule of law. Second, people facing extraordinary risks and costs have indeed acted with generosity and trust on a massive scale. And third, the fact that the individualistic and self-interested depiction of people in economics has been shown to be wildly inaccurate may also be a cause for alarm: people may care about others in negative as well as positive ways. The frightening upsurge of xenophobic attacks is a warning.

A consequence is that we have no choice but to reconsider the liberal creed that philosophers call preference neutrality, or what in economics is associated with the title of a famous paper, “De gustibus non est disputandum” (“There is no arguing about tastes”; Becker and Stigler 1977). The liberal creed and its economic variant effectively place the idea of better-or-worse values out of bounds for public debate and policy. But because the nature of our values is essential both to combatting the COVID-19 epidemic and to preserving a democratic society, we will have to get used to “arguing about tastes”, however uncomfortable that will be.

Among our values, fairness will be something that we will argue about a lot. We are now facing decisions daily – everything from grading students who are learning remotely with differential patchy internet connectivity, to triaging access to ventilators. Compliance with lockdown regulations will fray if they unfairly penalize those unable to work from home. The result will be to place ethical considerations at the centre of our national and global deliberations. These include but go considerably beyond placing a value on human life. And their intrusion into our daily conversations will enrich our economic vernacular.

No combination of government fiat and market incentives, however cleverly designed, will produce solutions to problems like the pandemic. What we call civil society (or the community) provides essential elements of a strategy to kill COVID-19 without killing the economy.

The dual elements of the new theory – the limits of private contract and governmental fiat, along with a new view of a (sometimes) socially oriented economic actor – open up a space in which economic discourse can engage with the pandemic, as illustrated in Figure 1. The blue line at the top is the left-right (government-versus-market) continuum of choices that has dominated policy debates for a century. We develop these ideas further in a related paper (Bowles and Carlin 2020).

Figure 2 An expanded space for policy and economic discourse

Note: the green arrows place COVID-19 related policies in the space; the black arrows are other examples.8

A point in the space opened up by the third pole, which we label civil society, has a similar meaning to a point on the bipolar blue government-versus-markets line. It represents how solutions to societal challenges can be implemented through a weighted combination of government fiat, market incentives, and civil society norms. (Coordinates of a point sum to one. The weight of each of these is the shortest distance of the point from the edge opposite the vertex in question. So, a solution represented by the vertex itself, such as “mandatory risk-sharing (transfers)” in the figure has a weight of 1 on government and zero weights for market and civil society.)

We characterise the motivations central to the workings of civil society by a series of other regarding or ethical values including reciprocity, fairness, and sustainability. Also included is the term identity, by which we refer to a bias in favour of those who one calls “us” over “them.” We draw attention to this aspect of the civil society dimension to stress that in insisting on the importance of community in fashioning a response to the pandemic, we recognise the capacity of these community-based solutions to sustain xenophobic, parochial, and other repugnant actions.

Figure 2 illustrates the location in “institution-space” of different responses to the epidemic. At the top left is the government as the insurer of last resort. Neither market nor household risk-sharing can handle an economy-wide contraction of activity required by containment policies; and neither can compel the near-universal participation that makes risk pooling possible.

Closer to the civil society pole are social distancing policies implemented through consent. The triangle opens up space for modern-day analogues of the so-called Dunkirk strategy – small, privately owned boats took up where the British navy lacked the resources to evacuate those trapped on the beaches in 1940. An example is the public-spirited mobilisation by universities and small private labs of efforts to undertake production and processing of tests and to develop new machines to substitute for scarce ventilators.

These examples underline an important truth about institutional and policy design: the poles of the institution space – at least ideally – are complements not substitutes. Well-designed government policies enhance the workings of markets and enhance the salience of cooperative and other socially valuable preferences. Well-designed markets both empower governments and make them more accountable without crowding out ethical and other pro-social preferences.

Much of the content that we think is essential to a successful post-COVID-19 economic vernacular is present in two recent advances in the field.

The first is the insight – dating back to Hayek – that information is scarce and local. Neither government officials nor private owners and managers of firms know enough to write incentive-based enforceable contracts or governmental fiats to implement optimal social distancing, surveillance, or deployment of resources to the health sector, including to vaccine development.

The second big change in economics gives us hope that non-governmental and non-market solutions may actually contribute to mitigating problems that are poorly addressed by contract or fiat. The behavioural economics revolution makes it clear that people – far from the individualistic and amoral representation in conventional economics – are capable of extraordinary levels of cooperation based on ethical values and other regarding preferences.

As was the case with the Great Depression and WWII, we will not be the same after COVID-19. And neither, we also hope, will be the way people talk about the economy.

But there is a critical difference between the post-Great Depression period and today. The pandemic of that era – massive unemployment and economic insecurity – was beaten new rules of the game that delivered immediate benefits. Unemployment insurance, a larger role for government expenditures and, in many countries, trade union engagement in wage-setting and the introduction of new technology reflected both the analytics and the ethics of the new economic vernacular. The result was the decades of performance referred to as the golden age of capitalism, making both the new rules and the new vernacular difficult to dislodge.

It is possible, but far from certain, that the mounting costs of climate change and recurrent pandemic threats will provide an environment that supports a similar symbiosis between a new economic vernacular and new rules of the game yielding immediate concrete benefits.

See original post for references

South Korea got “lucky” in that their initial hot spot was easily traceable to the religious group. Not sure if that is reproducible.

I suspect HK’s excellent response is due to their dislike of China, and skepticism over data coming out of China early on.

I disagree. Koreans extended testing well beyond the religious group. They tested everyone that could have had some contact with anyone infected, religious links apart. Whole neighbourhoods tested. According to David, In l´Alsace, France, it all started in a religious group but they did not control the spread. France was as “lucky” as SK in this sense.

The church membership list certainly seemed to give them a good head start. They could easily chase up those on the list, then test and trace a large number of potential cases. That must have allowed them to nip a lot of infection chains in the bud, before they blossomed and got to more elderly and infirm Koreans. Wouldn’t you think?

SK don’t just have Covid in Daegu – there has been a constant level of infection in Seoul and elsewhere, but (so far), they have managed to stop it spreading and going out of control.

They have done this primarily through aggressive track and trace through systems they had already developed and refined during the MERS and bird flu outbreaks.

As Ignacio suggests, the difference between SK and France seems to be the quality and speed of the response, not the nature of the initial outbreak.

Just worth noting also that, unlike in SK, the principal outbreak in France was at a religious festival, not within an established local church. Because of that, it was very hard to know exactly who attended, and for how long, and where they came from and where they went afterwards. Many of the attendees came from long distances, and some came from abroad. The French probably could have done better, but only the organizers had the data, and some of them were sick or disinclined to help.

It’s ironic, given the drift of the article, that many of the current problems arose from the activities of civil society groups, including churches. Other civil society groups meanwhile are lobbying for exemptions, organizing dangerous gatherings and spreading conspiracy theories, all around the world. We mustn’t fall into the trap (as I think the article does) of equating “civil society ” with the population at large. The volunteers in the UK are individuals, not “civil society” in any meaningful sense.

Yes, I found the triangular depiction odd in the way you point out that there may be “anti” civil society actors as well as “pro”

Why no Cartesian grid instead?

It is very important, and this can be deduced from your comment David, that SK success, less call it so, was not only consequence of bold action from authorities and institutions. One has to count, and this is important, the citizenship. The population at large was very much collaborative with the effort to contain the disease. This is quite important as I believe that denialism is still embedded in Western societies and this spells failure in our attempts to return to some kind of new normal.

The HK government does not dislike China – it is China’s puppet government and does pretty much what it is told by Beijing. But HK does have a far more advanced health system than China and a more focused and centralised government system, which no doubt helped. Ironically enough of course, you could argue that this is Britains colonial legacy.

Yes, that and their legal system. HK law and arbitration for international contracts was actually considered superior to Singapore or England & Wales until about 2016, when the thumb of the PRC started becoming evident on the scales with Chinese-linked counterparties.

One former expat exec I knew was prosecuted for unwittingly reclaiming HK Provident Fund contributions, acting on bad advice, when he left. It took him almost a year, but he was cleared of malicious intent by the courts, over the objections of the authorities who wanted some big fish to fry to show that such people are not above the law. The judiciary, a mix of Chinese and Westerners, was still independent then, but probably wouldn’t be today.

HK’s response was also due to the frontline healthcare staff willing to strike if greater measures weren’t taken. They had an institutional memory of past epidemics.

And there is Taiwan’s even greater skepticism. They are bullied by mainland China in the WHO, and had their own open source intelligence. Moreover, I think watched what China did (as opposed to their words). Taiwan was as vulnerable as any province in China, considering how much travel goes back and forth.

I suspect that HK and Taiwan also had many professional, informal and/or personal links between the healthcare and public health communities. The frontline workers could communicate and see WTF was going on, without a language barrier.

About language, Hong Kong people mostly speak Cantonese, while Taiwanese people mostly speak Mandarin. The written language is the same though.

The evidence does not support this from multiple countries around the world including Germany Australia South Korea Taiwan Singapore and Hong Kong. All of them have used agressive contact tracing testing and quarantine to shut this infection up

Yeah, we need a Covid-19 WPA for all the people losing their jobs asap. It’s the perfect answer to the problem.

It seems to me that South Korea got unlucky precisely because part of the outbreak occured within a religious group. Patient 31 seems to have been particularly idiosyncratic. She is thought to be responsible for at least 60% of South Korea’s outbreak and spread the virus while symptomatic for a week, and probably a couple of days more before that, before being pulled off the street. Italy and Spain were unlucky to start as well; Patient Zero in Italy was traced to the Atalanta-Valencia Champions League match in Bergamo attended by tens of thousands, including several thousand Spaniards. In the US we were fairly lucky in that our first cases were in a relatively contained nursing home — only Mardi Gras in New Orleans served as a massive vector.

The brilliant South African golfer Gary Player, used to say, “the more I practise, the luckier I get”, whenever he was accused of making a ‘lucky’ shot.

Well before that , French chemist Antoine Lavoisier said” Luck comes to the prepared mind”.

But a church list does not explain Taiwan”s success. Taiwan heeded China’s initial warnings to WHO on 2019-12-31 & 2020-01-07 and immediately activated their pandemic response teams. As of 2020-01-11, 385 cases & 6 deaths.

Nice start, and I’m wondering if perhaps a figure 3. creating a diamond shape with “personal liberty” at the top may be a more compelling model.

The tension between government and markets is similar to the tension between individual liberty and a civil society – for one cant exist without the other. When this diamond gets spinning like a top, each part contributes to the balance.

In the centre, regulating this tension, could be “transparency,” seemingly eroded for some time now, to assist in keeping government and the markets uncorrupted. Also in the centre, “our planet,” or perhaps “nature,” which we all rely on for our sustenance, the weight which stores the energy of the flywheel to keep the top spinning sustainably.

I’m sure there are many more figures incorporating further ideas from this fine audience.

A nice example of third-pole paradigms is detailed by E.F. Schumacher in A Guide for the Perplexed.

In his approach, two are divergent sides of a human problem and the third is the arbiter.

Two examples:

Liberty, Equality and Fraternity. Without the third, Liberty would favor the strong and Equality would discourage initiative. Fraternity arbitrates when.

Justice, Mercy and Wisdom. Without the third, Justice would require eye-for-an-eye with no extenuating circumstances. Mercy would forgive over and over. Wisdom, on the part of a judge, arbitrates when.

Schumacher held that convergent problems are those that are concerned with the non-living universe. Divergent problems are concerned with the universe of the living. The solution to divergent problems is to transcend them.

It may be time for ordinary people to develop a skill for analyzing between two points and know “when-to.”

Excellent comment!

Second

There is going to be plenty of blame to go around.

The WHO is not mentioned in the article, Nor are the statements from the Chinese foreign ministry and the articles in the Chinese press talking about how an American bought the virus to China. The article does cover our Idiot in Chief.

While I believe the following was not forced I believe it would be possible for a government to force something like that. As an example, how many Uighurs are in camps in China these days? How hard would it be to force those people be tested? Or any group in a similar situation? Any truth to the stories that they were forced into factories during this to continue working?

“As of 9 April, 494,711 South Koreans have been tested for the virus, a level of participation that would have been impossible to enforce on a recalcitrant citizenry by governmental fiat.”

Blaming China or any other country for America sitting on its hands and botching the response to this pandemic is a cop out.

At the end of December, 2019 the entire world knew about the novel coronavirus, which was confined to China at that time, and had plenty of time to get ready for its inevitable spread across the globe. The United States and many other “advanced” countries waited quite literally until it was on top of them to take action, which even then was half-hearted.

Is China also responsible for the success countries like Germany and South Korea are having in containing the virus? It is really embarrassing, not to mention dangerous, how the United States, land of innovation and rugged individualism, always blames its own failings and shortcomings on its self-created foreign enemies du jour. It’s the USSR, it’s Saddam, it’s Russia, it’s China….give me a family blogging break.

It’s called propaganda and the stuff about the WHO under the “thrall” of the CPC is fiction cooked up by neoconservative think tanks and happily disseminated by our feckless media.

Judging by the pervasive China-bashing, unfortunately many otherwise on-the-ball people are falling for it. Again.

You don’t even realize that the western media, by pointing fingers at the evil foreigners rather than holding those responsible in their own countries to account, is doing exactly what they are blaming China of doing.

When Mike Pompeo stands in front of his State Department podium and bitterly denounces China, Russia and Cuba for helping countries with much needed equipment, personnel and expertise, that really tells you all you need to know.

The United States of America can’t stand the fact that it is being beaten at its own game. And instead of improving itself and trying new approaches, our wise and learned leaders double down on the stupid and repeat the same failed policy (i.e., playing the unipolar superpower) ad nauseam.

I think the remark about Trump and the whole xenophobia thing seemed weak. I mean it’s Trump after all. Given that, it was probably put there to placate their social circle. You find that in many articles: person is being fair and reasonable but then they throw in some random cheap shot at the current out of favor person, be it Trump, Sanders, etc. As if to tell their establishment friends, who are being unsettled by reading the truth for once, that “I’m on your side really”! You can only be an outsider by so much I guess.

See Vygotsky’s “zone of proximal development”

That was interesting. Thanks.

Is not the “Civil Society” underpinned by “Rule-of-Law”?

Rule of Law which requires a respected Government, Not a Government of Oligarch boot lickers, always seeking money, and spending more than half their time looking for money to stay in office?

A very interesting initial discussion.

What triggered my curiosity is that there are a number of examples (in Fig 1) on the line ‘government – markets’, and other examples on the line ‘government – civil society’ but none on the line ‘civil society – markets’.

There is a definition that says that economics is the science of efficient allocation of scarce resources.

But who decided what objectives are targeted? If I have one field, do I grow a crop for export and earn money (as long as there are buyers) or do I grow a crop to have food on the table? There are risks and rewards in either option, and one needs a ‘choice’ (ie renouncing at the non-selected alternative). Economics should enter into play once the choice is made, but not in determining the objectives. That translates in something along the ‘government – civil society’ line on setting targets, and something else on the ‘government – markets’ line in achieving those targets. But there is no space for ‘markets’ to drive the choices of society.

A $ 6 Trillion and counting blow to Market ideology…

Venture capitalist in interview says we should let hedge funds fail.

Interview is going viral.

Does a Hedge Fund serve anyone but its principals and its investors? Does it have any value to society at large? If they are such rugged individuals, let them absorb loss as avidly as they suck up profit. Anyone and any institution that seeks to privatize profit and socialize loss does not deserve to exist.

I’m hoping that in the case of the UK that there will in the case of an inquest into the epidemic, that the non-implementation of recommendations from the 2016 Cygnus exercise are exposed, but I won’t be holding my breath.

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/03/28/exercise-cygnus-uncovered-pandemic-warnings-buried-government/

Enforcing Freedom of Information is critical. I can just hear the pearl-clutching “buts”. If you give the rabble all the current info they will get confused and run off a cliff like so many lemmings. I don’t think this is even close to reality. Give us all the information as clearly as possible and we will actually surprise you with how good and measured our judgement is. The true skill of a government is understanding how rational their subjects are. Actually all information is measured by the momentum of rational decisions. The decisions that are rational will outpace the other stuff. Not that government should “butt out” – not at all – it should go ahead with its own best advice, and also give it to us.

I’ve been calling for opening all the books, as it were, for more than 30 years…beginning in high school civics(where i was regarded as a dangerous crazy person, even then)

hyper-classification and secrecy first are anathema to the very idea of a free republic.

everyone still uses the rhetoric of liberty and consent of the governed and “it’s Our country”, etc. waving flags…and getting cross with weirdos like me who ask uncomfortable questions and have no use for blind patriotism.

we should either Be that way, for reals…, or stop the pretending…the Bosses cannot have it both ways forever.

hypersecrecy has played no small role in undermining the legitimacy of government…all these years later, and few can agree on “what really happened” with JFK, RFK, 9-11, and on and on.

with the initial escape of the internet, suddenly there were all these FOIA Docs just laying around(what i spent my first few years online doing), and it turns out “our” gooberment(and corps, etc) have done some pretty terrible things in our name….if not To us.

It’s natural that the perps and their heirs would want to put that back in the box…

but that’s not a good enough reason.

open it all up, with a lot of amnesty to go around, save in the most egregious cases, and move on as a stronger polity.

it’ll never happen, of course.

the Machine runs on the chaos.

the only american flag on my part of the place is a scarf covering a globe in my Library, as a sort of art piece.

norm de plume

April 12, 2020 at 12:55 am

Very well said ATH.

I recall a discussion with fellow travelling friends circa Iraq about the US – we were arguing about which word, if you had to chose just one, would best describe or explain America’s tragic and dangerous decoupling from the rest of humanity in the wake of the Cold War.

The usual suspects came first – hypocrisy, hubris, greed, the will to power (which is three words I know, but). Later someone suggested ‘fear’ which I thought had more explanatory power as it could be argued that it lay underneath some or all of the above, in a Thucydides Trap kind of way. Then someone suggested ’secrecy’. It fails to cover as much ground as some of the others but it can’t have too many rivals as a key characteristic.

This was around the time the US was trying coerce the rest of the world into official approval of the Iraq ‘War’, really ‘Massacre’. Part of this effort, we discovered involved a massive operation to infiltrate the phones and laptops of every single member of each nations’ delegation, down to the secretaries and drivers. Mics and cameras remotely accessed, etc. Later reports indicated that this approach had already been used in corporate settings, so that US firms had illegally obtained private information upon which to base strategies for negotiation. Did even one US official admit this? Did one emit even an iota of shame?

You may recall a Pew report (I think) that shockingly showed that the rest of the world thought the US the greatest danger to them. There was even a mooted globally televised ‘What we want to tell America’ event planned, I can’t recall if it even went ahead but it was certainly not appreciated in the Land of the Free. The basic message to the US was – you had it coming and this is why.. but fingers remained firmly stuck in earlobes. In these Trumpian times it pays to recall that the global mistrust amounting to disgust at US behaviour is of long standing.

All this was at a time when demonstrable falsehoods were being peddled by empire flacks like Powell and Blair, perhaps the only two who could, if they’d bothered to try, have derailed the train to an illegal war. Rumour had it that plans for invasion were ‘on the table’ even before 911. Then once it had begun, we were told fibs on a daily basis, and we realised that these lies were only being manufactured to cover atrocities that hadn’t been obscured successfully enough, leading us to wonder what else might lay hidden. Some of us saw confronting images of the abuse of dead Iraqi bodies one day on the net and were unable to find them the next. 9 billion bucks went missing from a dollar shipment, was it ever found? Who knows?

‘hypersecrecy has played no small role in undermining the legitimacy of government’

Yes – each iteration of attempted secrecy may ‘work’ and so might the use of disinformation to muddy the waters – mission accomplished, heckuva job – but the cumulative effect is as you indicate fatal to perceptions of government’s trustworthiness.

I guess this can be placed within the very useful frame provided by the late Chalmers Johnson:

‘A nation can be one or the other, a democracy or an imperialist, but it can’t be both. If it sticks to imperialism, it will, like the old Roman Republic, on which so much of our system was modeled, lose its democracy to a domestic dictatorship’

Noble lies of the Leo Straussian variety are necessary to maintain an empire abroad, but are eventually fatal to democracy at home.

The response in the US has been so bad, I don’t think the messaging is going to matter much. I think it will be similar to Lyndon Johnson during the Vietnam War where every order of magnitude increase in casualties caused a 10% dip in his approval rating.

Apparently, it is now getting into the rural communities, many of which have aging populations and no hospitals. https://news.yahoo.com/coronavirus-slow-spread-rural-america-122824791.html

Unless they are taking social distancing very seriously, the growth can be explosive. NYC only had its first confirmed case on March 1. This is a good presentation discussing social distancing with current data: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xx63-5As-Uw&feature=emb_logo

This isn’t going to be over soon.

So there is hope that the sociopaths will no longer be able to convince the majority that their behavior is normal and to be reinforced and emulated?

That’s a pretty juicy thought.

One has to wonder if the threat of Sanders, which caused such a voracious response by the establishment, had less to do with his possible actions threatening their ill gotten gains and more the threat to their worldview. If so, any article that stresses the importance of community for a functioning society – I mean nation sorry Thatcher – is to be cherished.

Has anyone here see any payment out of the few Trillion in their Bank Account?

Even as little as $ 1.

It would be interesting to track the payment of monies in the same manner as infection and deaths….Lets say three pieces of data Date received, Zip Code, and Amount.

I think age would be a key marker. SocSec. recipients already receive direct deposit disbursements and most will qualify, since the average annual income is about $30K. I know, they didn’t lose a job. But it’s easy and quick and Le Orange can then tout the rapidity of disbursement on TV.

Great! But should not it be L’Orange?

>>I know, they didn’t lose a job.

Really??? I am pretty sure I am not the only one on this site who is on SocSec and DID lose a job. I’m not working after retirement age because I WANT to; it’s because I have to and will have to for the rest of my life thanks to the financial crisis, which turned my whole life upside down. There are many more just like me.

Sorry for the rant, but I really am tired of lazy assumptions that seniors on SocSec don’t have to work or that seniors don’t want to “share” Medicare with everyone else who’s not on it. Just like every other categorized group, we aren’t a monolith of people, set in stone, with a uniform set of ideas/thoughts/circumstances.

“The pandemic of that era – massive unemployment and economic insecurity – was beaten new rules of the game that delivered immediate benefits.”

It was three years after the 1929 Crash before FDR was elected and then another 6 months for his 100 days to be underway. So FDR was elected at the depths of human misery. Simultaneously as FDR being elected, Hitler was taking firm control of Germany so these things can swing in multiple directions depending on relatively minor differences in circumstances.

FDR immediately put in place a series of people who had ideas and knew how to execute them. He wasn’t looking for sycophants, he was looking for doers. They were all willing to experiment and ended up with an alphabet soup of agencies with one aim – get American people back on their front doing productive things from building roads and dams to making art and music. But that only happened after three years of austerity and bad monetary policy.

Neoliberal patron saint ‘Hoobert Heever’ had his own side of the story of course, which Scott Alexander summarizes with equanimity over at SlateStarCodex.

I think one of the proofs of the effectiveness of some of the key New Deal legislation was the absence of financial system collapses and major recession/depressions due to financial system collapses until the New Deal legislation was repealed, a decade after which they started up again. Up until Glass-Steagal, there were numerous “panics” and “depressions” every few years from the Civil War into the Great Depression.

Is anybody even talking about the effectivess of the Chicago School -Laffer tax cut bill from 2 years ago? Its economic impacts are not visible at all but the impacts on the deficit are up there in neon lights.

Sociopaths are in charge. So that’s what you’re up against.

They understand power, not reason.

The classic on the social sector “The Age of Social Transformation” was written by Peter Drucker in 1994, available here:

https://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/issues/95dec/chilearn/drucker.htm

Many, many thanks for this. Rereading Drucker had been on my short list.

Like Marx, there is so much he gets right, but a few key items where he seems to get both the sign and the amplitude of the trend badly wrong.

Before the First World War, farmers still made up a near-majority in every developed country except England and Belgium. The second-largest group in the population and work force of every developed country around 1900 was composed of live-in servants…. But as classes, they were invisible [fragmented, unable to be organized or stay organized].

Fifty years later, in the 1950s, industrial workers had become the largest single group in every developed country, two fifths of the American work force. Unionized industrial workers in mass-production industry had attained upper-middle-class income levels.

But thirty-five years later, in 1990, industrial workers and their unions were [once again] less than one fifth [now one eighth or so].

Fair enough. And now we get into the futurist Drucker:

The newly emerging dominant group is “knowledge workers.” They require a good deal of formal education, and the ability to acquire and to apply theoretical and analytical knowledge. Above all, they require a habit of continuous learning.

Knowledge knows no boundaries. It is not tied to any country. It is portable. It can be created everywhere, fast and cheaply. Finally, it is by definition changing. The knowledge society will inevitably become far more competitive than any society we have yet known.

Fair enough. Now Drucker starts flagging the weak spots, but his assumptions start becoming tenuous:

1. There are obvious dangers to this. For instance, society could easily degenerate into emphasizing formal degrees rather than performance capacity. It could fall prey to sterile Confucian mandarins–a danger to which the American university is singularly susceptible. On the other hand, it could overvalue immediately usable, “practical” knowledge and underrate the importance of fundamentals, and of wisdom altogether.

Hell yes!

2. The knowledge society will inevitably become far more competitive than any society we have yet known–for the simple reason that with knowledge being universally accessible, there will be no excuses for nonperformance…. The world economy, rather than the national economy, is in control.

Check. Drucker correctly read that the online revolution and the end of the Cold War would quickly put the West in direct competition with smart motivated people in Guangdong and Bangalore. That toothpaste is well and truly out of the tube.

3. The essence of a knowledge society is mobility in terms of where one lives, mobility in terms of what one does, mobility in terms of one’s affiliations. People no longer have roots.

So learn to code and move out to the coasts, slackers! away from Mom’s basement and into the waiting arms of your friendly rentiers and usurers.

4. In the knowledge society, knowledge workers own the tools of production. The true “capital equipment” of market research is the knowledge of markets, of statistics, and of its application to business strategy. This knowledge is lodged between the researcher’s ears and is his or her exclusive and inalienable property. Capitalists will therefore need knowledge workers far more than knowledge workers need them.

BZZZZZZZZ!!!!!! So sorry Peter, thank you for playing. Race to the bottom is the actual dynamic you were looking for, no matter how hard you work or how good you are at taking tests.

Deprived of any ability to organize and cartelize his skilled labor via a guild, the fragmented ‘knowledge worker’ has about as much bargaining power and control of the means of production as Amelia Badelia, the stereotypical dumb Irish housemaid of the 1910s.

4. In the knowledge society, know-how becomes performance only when applied in action, and the worker derives his rank and standing from the situation…. The central work force in the knowledge society will consist of highly specialized people, working in teams.

The managers make knowledge productive by bringing people–each possessing different knowledge–together for joint performance. It is the organization, not the individual, that performs.

In its own mind anyway. In fact, the credentialed managers (PMC) set themselves up as a priesthood or courtier class, judges of who gets to join the team and who is ‘effective’ once there. An entire new HR-education-consulting complex springs up to help them decide who is worthy.

Play the game or you’ll be replaced instantly; but frankly, you’ll be replaced anyway the moment you get too expensive.

While Drucker observes correctly that revolutions since 1775 are not in fact bottom up revolts by peasants or proletarians, even though they may take place in the name of those classes, he misses that the leaders are in fact the ‘reserve army of the underemployed governing class’.

That is, they come from the ‘failed’ overeducated baristas and gig workers who, for whatever reason, didn’t attain one of the available slots in the hierarchy and therefore lose little from its overthrow. And the more penniless frustrated coders the system creates….

In the graph a green arrow says; “20k Qantas workers hired by government as contact tracers”. Weeks ago I wrote here that fired Peace Corps Volunteers should be hired to do this. Nada! Donald Trump tried to stop funding coronavirus testing. He backs down. Now he wants to reopen the country on May 1st.

The “marketplace rules” is why the USA is in first place for confirmed cases of COVID-19. Contact tracing is likely why Australia is halfway between the UK and Japan. The Western Empire still fails to admit that it has ceased to exist since it let the coronavirus pandemic run wild. Since the Iraqi invasion in 2003, the US federal government has done what the Global Plutocrats want, not what is best for Americans. Donald Trump’s whole being is wrapped up in being on the top rung in the marketplace, not Barrack Obama.

The USS Theodore Roosevelt is the latest example of stupid ineptitude. American troops in Syria and Iraq are in the same position as commonwealth troops in Philippines after Pearl Harbor. Except Donald Trump is no FDR and Joe Biden still believes that he is the nonexistent empire’s point man. Neither can see that a return to a civil society is what is needed to end the calamity of both a pandemic and a depression at the same time; not to mention, climate change and a nuclear armed multi-polar world which continue to loom large.

Oh, pull the other one!

Just hoping that I can learn Korean at my advanced age. The cuisine is fabulous!

My thoughts too! I’d actually planned to start Korean lessons in September if the colleges here are open. I visited SK for the first time last year and I can confirm, the food is very good (although limited for vegetarians like me). But the good thing about food in Korea is that the people have a very good palate, so even non Korean food prepared by Koreans is really good – one of the best pasta dishes I’ve ever had outside of a ‘real’ Italian place was in Seoul.

Limited for vegetarians but SKorea is the world’s largest consumer of tofu per capita. I suspect that one could find some good spots, there must be some vegetarian social networks in SK. And where did seitan or gluten protein products originate? I’ve heard Buddhist monks ~1000 years ago. I think there have been and are some in Korea.

The Corona pandemic portends changes in the world After Corona. The response of Governments in the U.S. and Western Europe greatly undermines any esteem they may still have held in the eyes of the world. The failures of Government, the Public Health Bureaucracy, and our Medical Industrial Complex in the U.S. have been colossal, as has Globalization with its long lean, and fragile supply lines. The Finance driven economy has been gutted — ready to collapse at the first trigger, and already prepared with a plan for exploiting that collapse. The Corona pandemic makes a perfect trigger to launch another bigger and better transfer of wealth into the hands of Big Money while creating new opportunities for consolidation and plunder. The destruction of small business has a twofold advantage of opening new business opportunities for Big Money expansion and creates a bigger, better, more desperate pool of unemployed — who without some further actions will face several months rent, mortgage payments, loan payments immediately due and payable After Corona.

But this post paints a more pastel picture of events. We have “opportunity for a long-needed fundamental shift in the economic vernacular”. The post contrasts the need for Big Government to handle the epidemic with the overreach of the FDA regulations “preventing academic and clinical labs” from helping out. The discussion that follows then deftly shades effective Government action as somehow authoritative government action but blurs things a little with suggestions of the place of “cooperativeness”.

We come to pronouncement 1: “No combination of government fiat and market incentives, however cleverly designed, will produce solutions to problems like the pandemic.” Which leads to the colorful triangle diagram — a pretty picture reminding me of TED talk slides and Corporate Pep talks, and so many PowerPoint Presentations by this or that expert trainer called in to teach all to behave as good little employees. The diagram doesn’t explain much to me but it does raise my antenna.

After wading through some warm touchy-feely discussion of civil society, community, human goodness we come to this pronouncement 2:

“Well-designed government policies enhance the workings of markets and enhance the salience of cooperative and other socially valuable preferences. Well-designed markets both empower governments and make them more accountable without crowding out ethical and other pro-social preferences.”

How exactly do “well-designed government policies” and “well-designed markets” contrast with “cleverly designed combinations of government fiat and market incentives”? This whole idea of a well-designed market sounds terribly familiar, as does the idea “dating back to Hayek” that “information is scarce and local” — which means what exactly? Why not just make plain that Markets alone can fathom the information needed to create an optimal Society — which dates back to later in Hayek’s thinking of Markets as the ultimate tool of epistemology. The concept of “well-designed markets” as a problem solution could not be more Neoliberal.

The post closes with an odd twist touting “symbiosis between a new economic vernacular and new rules of the game”. Strange what’s in place — the CARES Act — while we wait for this symbiosis — although I still cannot shake my thought that the word parasitism better fits the new version of the old relationships.

Isn’t this the basic idea behind Adam Smith’s “Theory of Moral Sentiments?”

Yes, the triangle was a way to classify things and in so doing trying to simplify a complex situation. Because humans are complex beings. For me, it was too simplistic, so I’m wondering who the intended audience was. It should be gov vs private enterprise, yet then monopoly vs markets, yet communal vs individual, yet then corporate (in the original sense as taking risk) vs conglomerate (minimizing risk). Etc. The choices a society makes should come down to judgement calls based upon the evidence about what is best, often as a compromise between the competing elements in the society or in an individual him/herself. And what will be regarded as best will change with time as new evidence comes in. I was a pinhead libertarian at one time, but I’m not embarrassed about it (ok, a little). Currently, we have a lot of changes that should be made that should be regarded as low hanging fruit in the intellectual sense. Such as universal health care. But if the people doing the judging are corrupted by the very system they are living in currently, what do you do? Move to South Korea as some above flippantly suggest? Or just keep hammering away until the dam bursts? Or??? Civilization is a fragile thing I guess.

Jeremy, my comment was meant to be in your thread. I’m trying a new browser and it’s knowledge of JavaScript could use some work.

I love the analysis, but it leaves out an important fourth pole: technology. Much of the difference between

medieval institutions and modern ones have little to do with philosophy, and much to do with the fact that we have cheap energy and free flow of information.

I live in the same lock down as the rest of the world, and despite the acts of government, almost all aspects of my experience have been due to individual decisions made by my employer, family, neighbors and my internet community about social distancing that long preceded the government and will long outlive their guidance. The 2020 Covid pandemic was stopped far faster than the 1918 spanish flue pandemic for the simple reason that information traveled faster, and technology based industry made the world less on-edge of starvation.

It can be argued that the governments AND markets become less critical as technology supports our natural institutions.