Yves here. A few days ago, we ran a post on how different the Covid-19 infection rates were in two neighboring Queens communities, Flushing, which has a large Chinese population, and Corona, which is strongly Hispanic. One reader pointed out that the Latin culture likely played a role, with hugging, backslapping, and physical closeness in social interactions common. Looks like he was on to something….

By Jean-Philippe Platteau, Active Emeritus Professor of Economics, University of Namur and Vincenzo Verardi, FNRS Associate Researcher; DeFiPP, University of Namur. Originally published at VoxEU

One puzzle that arises in connection with the spread of Covid-19 is why there is such large variation in infection and death rates both across as well as within countries. This column argues that differences in the way people, and in particular different age groups, interact can explain part of this variation. Simulations show that the measures Belgium would need to take when re-opening its economy would be more moderate if it had the same interaction patterns as Germany, and more strict if it had Italy’s interaction patterns. A key lesson is that there is no one-size-fits-all solution that could be applied to all countries, or even to all regions within a country.

One puzzling question that arises in connection with the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is why there are such large variations in its incidence (the infection rate) and its lethal consequences (the death toll) across countries as well as across regions within countries (Economist 2020: 16-17). In Europe, there is a striking contrast between the relatively low rates of infections, hospitalisations, and/or mortality in countries like Germany, Austria, Scandinavia (with the exception of Sweden) and in Eastern Europe and the relatively high rates observed in countries like Italy, Spain, France, the UK, Belgium and the Netherlands. Equally striking are the intra-country variations found within some countries, such as Italy, France and Switzerland. In the latter, the French-speaking part, Romandy, has epidemiological statistics close to those of France, the German-speaking, Alemanic part shows a strong similarity with Germany and Austria, while the Italian-speaking part, the Tessin, shows a strong similarity with northern Italy.

Many confounding forces are obviously at play, including geographical factors (population density, the role of super-drivers, etc.), genetic determinants, public health policies, and social or cultural characteristics. In current debates, attention has been mostly focused on explanations that privilege public health facilities and policies, including the capacity of the government to plan and anticipate and its ability to act decisively early enough in the propagation of the virus.

Recently, however, awareness of the role of genetics has been raised by a team of researchers from Ghent University in Belgium. According to this team, part of the intra-European differences in the intensity of the epidemic are attributable to genetic variations: some population groups carry a gene (ACE1) that facilitates the fixation of the SARS-CoV-2, while other groups exhibit a higher frequency of the polymorphism D of the same gene, which makes them more resistant to this virus (Delanghe et al. 2020). Interestingly, the more one moves toward the eastern parts of Europe, the higher the incidence of this favourable variant of the ACE1 gene. It is not only Eastern European countries but also Austria-Germany, Scandinavia, and southern Italy (where the Norman conquest left its biological imprint) that are within the zone where the polymorphism is found. Spain, Northern Italy, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom are not.

The Role of Culture

In our current research, we aim to bring to light the possible influence of local cultures. So far, cultural variations have been mostly conceived as differences in the attitudes and gestures displayed by people when they meet. The Japanese habit of keeping a reasonable distance, for example, is in stark contrast to the Western European habit, especially in southern Europe, of kissing and hugging friends, relatives, and acquaintances. Moreover, in some countries like South Korea, China, and Japan again, people are accustomed to wearing face masks as a way of protecting themselves against air pollution – an attitude which is something of an oddity in Europe. It is clear that these East Asian cultural habits are a big advantage under an attack from a virus when it is precisely these attitudes that are conducive to effective protection from contamination.

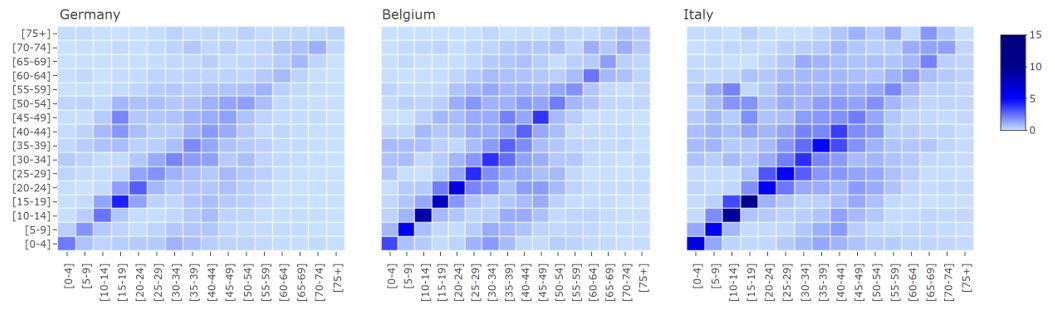

Here, we look at another component of culture, namely, the frequency of contact between people. For example, the Italian society is strongly centred on the family, and relatives pay frequent visits to each other. In Scandinavia and in German-speaking areas, by contrast, interpersonal contacts are less frequent. Fortunately for our purposes, ‘contact matrices’ have been estimated for a large number of countries, which display such contact frequencies, assumed to be pre-determined, both within and between different age groups. A simple glance at these matrices shows, for instance, that the density of contacts is comparatively high for Italy and much lower for Germany; Belgium occupies an intermediate position (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Interaction matrices for Germany, Belgium, and Italy

Source: Prem at al. (2017)

To use this information in the most persuasive manner, we have carried out a thought exercise in two steps.

- First, using a standard epidemiological model (the age-structured SEIR model), gauged on Belgian data, we simulate the effects of different lockdown exit strategies on the evolution of the epidemic, once its peak has passed.

- Second, we repeat the same simulations after having replaced the Belgian contact matrix successively by that of Germany and that of Italy on the date of the exit from lockdown (Platteau and Verardi 2020).

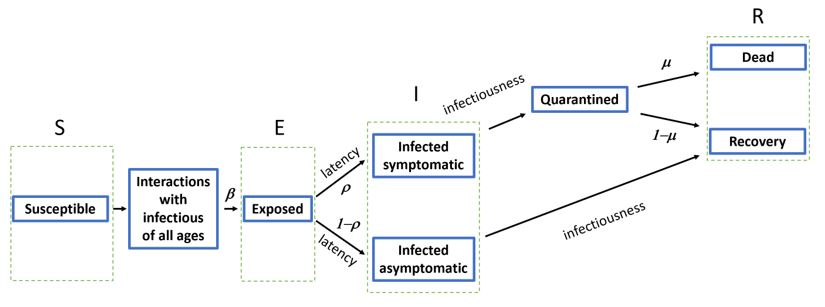

The SEIR model is widely used by epidemiologists to simulate the evolution of a pandemic (Adam 2020). Its underlying structure is described in Figure 2 (for one reference age group) where we see that the population is divided into four groups (compartments) of individuals. Group S are susceptible individuals, that is, those at risk of being contaminated;1 group E are individuals who have been exposed to the virus; group I consists of individuals who were in group E but for whom the latency period is over so that they have become infectious; finally, R is the group of individuals who were contaminated but had an outcome (either a recovery or death) and are no longer infectious.

Figure 2 The SEIR epidemiological model

Economists are increasingly trying to improve our understanding of several aspects of the Covid-19 crisis (Baldwin and di Mauro 2020a, 2020b), and they have characteristically chosen the same model as their basic scaffolding, onto which some behavioural function is possibly grafted (e.g. Alfaro et al. 2020, Brotherhood et al. 2020, Forslid and Herzing 2020, Ichino et al. 2020, Jarosch et al. 2020). Our own efforts consist of making the SEIR model ‘speak’ in terms of exit strategies aimed at (gradually) re-opening the economy, with the aim of then examining the specific influence of particular contact habits.

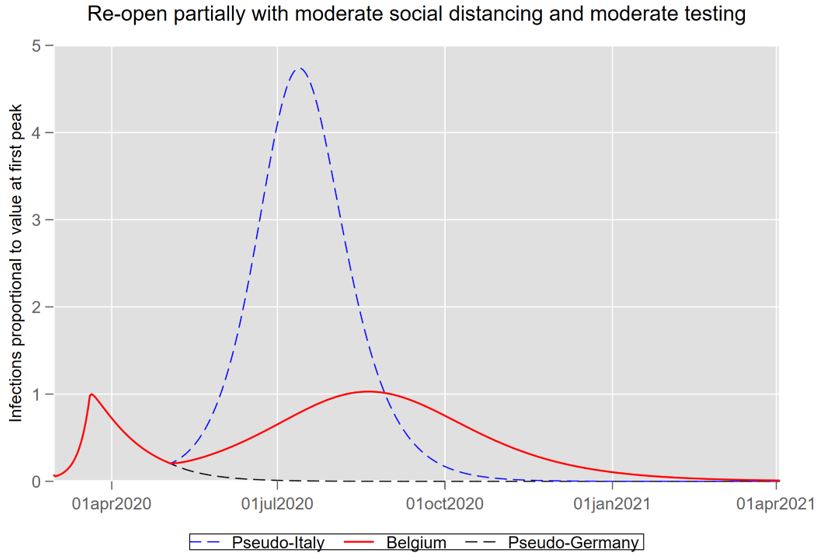

The results are striking. If Belgians had the contact habits of Germans, they would be able to (gradually) re-open their economy by resorting to milder measures than they actually need. And, conversely, if they had the contact habits of the Italians, they would need to use much harsher measures. More concretely, with their own culture Belgians must implement rather ambitious testing (and contact-tracing) schemes and enforce rather strict social-distancing measures if they want to avoid a significant rebound of the epidemic while re-opening their economy. If they had German interaction habits, they could avoid a rebound by implementing more moderate measures of testing and social distancing. But if they had Italian interaction habits, they would have no choice other than to implement more severe public health policies and proceed much more slowly in re-opening the economy. In particular, testing would have to be more established before starting to re-open and social distancing would have to be more stringently enforced in the course of the re-opening. This is essentially what Figure 3 is telling us with a stereotyped exit strategy.

Figure 3 Comparative evolutions of the Covid-19 epidemic under a moderate lockdown exit scenario: Belgium, pseudo-Germany, and pseudo-Italy

Conclusion

An important lesson is that a country like Germany is probably benefitting from all the advantages that work towards a comparatively smooth lockdown exit: (1) it possesses a strong public health infrastructure and has chosen sound public health policies that prepared the ground for an effective battle against Covid-19; (2) its social norms that guide individual behaviour, including habits regarding meetings and visits, help slow down an epidemic; and (3) its people might possess genetic characteristics that make them less vulnerable to the virus.

Contact frequencies may also provide a (partial) explanation for the aforementioned variations within Switzerland, where, in terms of rates of infection and deaths, the French-speaking part is close to France, the German-speaking part is close to Germany and Austria, and the Italian-speaking part is close to northern Italy. It is true, on the other hand, that important variations, such as those observed between northern and southern France, are not accounted for, confirming that there is no one explanation for all the geographical differences observed. However, there is a key lesson to draw from our work and from the foregoing discussion: there is no one-size-fits-all solution that could be uniformly applied to all countries, or even to all regions within a given country. It is perhaps no coincidence that the EU has been unable or unwilling to suggest, let alone prescribe, a common lockdown exit strategy for all its member states, leaving them free to make their own decisions on the matter. The diversity of peoples and cultures within Europe is too large to allow for a general solution to the complex problems raised by the present pandemic. The same conclusion also applies to large federal political entities such as India, Russia, and the US.

See original post for references

There are some claims that Asians are genetically less susceptible to Covid-19 than westerners:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41421-020-0147-1

I think this is considered bogus by many, though:

https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202002.0258/v1/download

And China certainly had bad outbreaks, though if the claim is true then it could have been even worse.

A current morose joke in Finland: “These social distancing guidelines are crazy! 2 meters?! Why so close?”

I don’t think there is any other form of joke in Finland than morose ones… (but they can be very funny).

this is also pretty funny and relates to the inherent Finnish cultural need for social distancing.

https://www.boredpanda.com/finnish-nightmares-introvert-comics-karoliina-korhonen/?utm_source=google&utm_medium=organic&utm_campaign=organic

My favourite uncle was from Finland and he would recognize these jokes.

I’m reminded of a Finnish Joke;

A Finnish man is looking out the window;

“Ah the children are coming home from school. There would be more of them, but there are wolves in the woods.”

That’s actually VERY funny. Almost as good as the one I saw in the UK:

“The people of Scotland can exercise more than once a day”, says Nicola Sturgeon

“Whoa, whoa, whoa, let’s not get carried away!” says Scotland back

Holy cow that captures my viewpoint. I hate crowds and urban areas.

This is a massively complicated issue, and one important reason of course as to why so many existing models have proven to be pretty poor at predicting the virus’s march. Other issues I’d add to the list would be immunisations (there seems to be a link between some types of TB immunisations and protection) and things like diet and Vitamin D levels.

But when you look at a very granular level, there are huge variations even within relatively homogenous societies like Ireland. If you look at the spread in Ireland, there is an arc from the main city (and airport hub), Dublin, up the north coast and across the sparsely populated border areas. The south of the country is almost entirely free, with just one cluster in the south-west which, I’ve been told, is associated with a school group that got infected on a ski trip to Italy. Northern Ireland is relatively free, although the slower response there to reporting and testing might have distorted the figures.

On culture, its undoubtedly significant, but I wonder if again, the differences are more apparent than real. Anyone who’s travelled north to south along Europe will know that there is a very significantly increase in social difference the further north you go. Just sitting at a table in a bar or restaurant feels different, there is much more space the further north you go. But then again, there are counter example ‘hotspots’, as anyone who’s been along the Reeperbahn in Hamburg on a Saturday night would have experienced.

Even in Asia, the cultural issues can be complicated. The Japanese maintain a strict social distance in most of life, but when they go out drinking, its the entire opposite – lots of small, cramped bars with dubious toilet facilities – much the same in South Korea, and in the more Chinese influenced areas restaurants can be similarly less-than hygienic. Thats one reason why I was so surprised that they didn’t shut down bars in SK and Japan, but perhaps they knew that any outbreaks there were controllable.

Just one factual point about the article – it states that mask wearing is a protection against air pollution. I’d always been told by Chinese and Japanese friends that mask wearing was mostly by people who have sniffles and colds and it is seen as protecting others. In other words, it has always been about reducing infection and a courtesy to others, not a form of personal protection.

Yes, I’m a bit sceptical about this Friedmanite tendency to make cultural generalisations. In Japan a lot of what people see as social distancing is actually giving people psychological personal space in a country where only 5% of the land surface is habitable, and many people live and work crammed together in far less actual personal space than would be the case in the West. But it’s all very context dependent : as you say, go to bars or yakitori restaurants, travel by train at rush-hour, try to cross a road at a major intersection or walk through a station entrance and you understand what “crowded” actually means. SK is the same, though from observation there’s less social distancing because there’s more space.

Incidentally, this bit quite defeated me:

“It is not only Eastern European countries but also Austria-Germany, Scandinavia, and southern Italy (where the Norman conquest left its biological imprint) that are within the zone where the polymorphism is found. Spain, Northern Italy, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom are not.”

So the former have this useful polymorphism, but the latter, not having had any contact with the Normans don’t? Pardon me?

interesting purported fact: the average home in England (dunno about Scotland) has less sq footage than those Japan or Germany.

don’t take my word for it….I heard it on a BBC interior design show.

wife’s mexican familia are huggers, in line with the above.

so are my czech and irish lineages.

the more german idealist ancestry a person has out here, the more opposite they trend(our Lutheran Churchfolk are noticeably standoffish in aggregate)

I’d never thought of this before…behavioral aspects of ethnicity…in relation to public health like this…until “Backslapping Gregarity” came to figure so prominantly in our local outbreak.

Haven’t culturally ingrained contact habits been replaced by a new form of supranational habit called social distancing? We black Africans hug and touch frequently during social interactions, perhaps even more so than Italians and those from the Iberian peninsula but I’ve seen people snap out of that behaviour pretty quickly since the messaging around social distancing started saturating the airwaves. My friends in Botswana, Namibia and Mozambique tell me it’s the same over there.

I obviously can’t speak for Europe but isn’t the musing on culturally ingrained interaction habits vis a vis lockdown exits rather moot if everyone regardless of culture is practicing the new normal aka social distancing?

PS: sorry if this ends up being a double post, my previous, identical comment disappeared.

Thuto

excellent observation. up til two months ago mexican’s greeting each other here in California gave each other abrazos, hugs and kissed closest friends. i see very little of that anymore (as you point out with black Africans) day laborers typically stay masked up til they get home and social distancing also typical. it makes sense as behavioral theory but unless there was a significant drop in cases following lockdown/shelter in place orders i would say this requires closer tracking. possibly there are graphs of cases with demographics at county level. worth looking into.

gonna look at tulare county. 7 billion in agriculture, 65% hispanic/latino populace. difficult to locate past data. currently 1,334 reported up 32% deaths 64 up 45%. giving further thought, with the fomites type of spread (cramped housing and horrible latrine facilities on job) even observing social distance/masking up, without access to other hygiene supplies still gonna be like life in a petri dish

The Greek situation is another example like yours. The are doing just fine, albeit with the cultural background/habits that the authors would be identifying as dangerous. They took the right precautions early on. I understand that Cyprus, Greece, Lebanon and Israel have lifted travel restrictions, but only for residents of the other three countries.

Very interesting analysis. Lots of variables (contingent and otherwise) to unpack.

My personal observation on social distancing is that some people do it better than others. In my town there are groups of young (teens) and older moving about town and congregating in non-familial groups. Some intentionally move within “social distance” of strangers. It’s a game; likely with a poor outcome.

It’s likely that “re-opening” the economy is very likely to spread Covid-19 more deeply in the US, and elsewhere. The more people infected the greater likelihood of a chance encounter with a pre-symptomatic virus carrier will lead to greater stress on health workers and more death.

Some will take their cultural behavior to the grave.

>other groups exhibit a higher frequency of the polymorphism D of the same gene, which makes them more resistant to this virus (Delanghe et al. 2020). Interestingly, the more one moves toward the eastern parts of Europe, the higher the incidence of this favourable variant of the ACE1 gene.

Admittedly, only skimmed this article. But, does not the high prevalence of Covid-19 in Russia undermine this claim? What am I missing? (and, while parts of Russia are in Asia, Russia is considered an eastern European nation).

‘Tis the exceptions disprove the rule.

Too many things don’t quite fit the ‘Norman gene’ picture.

Here’s a link to an element of culture that the article author may not have considered:

https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-05-16/coronavirus-mothers-day-church-service-butte-county (paywalled)

The article is about a Mother’s Day church service attended (unwittingly?) by a person subsequently testing virus positive. Butte County, CA health officials opposed the “re-opening” by elected officials. The cost of testing and tracking the ~180 service congregants will fall to the general public, not the church.

Think of the rising unemployment, all of this new “cliquishness” that will arise from Covid, and online job applications at the mercy of these algorithms….

If you don’t already know some people in the field you are trying to work in, you will have a hardee time making connections.

I don’t buy these “Zoom” video meets will benefit people trying to form new networks like striking up a conversation in public or at an event.

And I’m already hearing about “secret” events being held for people with connections.

My Thai wife hadn’t seen her mother in 4 years. No hugs, but lots of waiing. I found it very moving.

I don’t understand the need to hug acquaintances or even friends, it’s like everyone’s on the set of the Oprah show.

IME the hugging is a mark of insincerity – the biggest huggers aren’t around when you help you move or visit you in the hospital.

And then there is hostility. As I walk around my PMC neighborhood, there are loads of people out, and I always, always am the one who crosses the street or walks in the middle of the road in order to be polite. But yesterday I was distracted for once; I was on my cell phone talking with a friend who is stuck inside. Yes, I erred. Suddenly a woman my age and ethnicity walked closely past me. It was intentional; it was the strangest thing. She was angry because I had not given way, and she expressed it by walking close to me. The funny thing was that of course that wasn’t good for her either. I’m not thinking there was some big hazard, except for her psyche. My religion requires that I not be annoyed at that sort of thing, so I wasn’t; just startled.

I wonder if some subcultures have larger quantities of self-defeating hostility.

This is interesting. I am surprised that no one has made a hierarchy of coronavirus risks. Nursing homes, prisons, meat packing plants, choirs, cruise ships, aircraft carriers and church services are super spreader sites. Neoliberalism in the USA, UK and Russia heightens the risk. Communism in China, Vietnam and Cuba lowers the risk. Hugging and kissing is way too close. Retired in a suburban home, resupplied by Amazon, should lower the near-term risk to near zero, until cabin fever or health forces a recon outside.

What makes the severity and length of the risk of a COVID-19 infection unknowable is the failed federal government that does not do universal testing or contact tracing; over-laid by magical thinking in the White House. The risk of unrest increases with time.

The reality simple as it seems is that Covid-19 is an infectious disease. The formula for catching it is viral load x time. So, a sneeze near you will do it. 30 minutes with someone infected breathing will do it. The effect of getting infected slowly v. all at once. Then there the disease – As in how sick you get, when you get sick, how long your sick, if you need intensive care, and lasting disabilities. Then there are special cases for children, those over 75, and adults from 25-50 who may develop heart, liver, & brain damage in an unexpected manner. In general 20% of those infected get sick, 50% of those very very sick, and of the initial 20% – 5% or so die. Obviously, there are about 100 variables in play. In the United States given the state of the federal Gvt and trump’s insistence on undermining everything, the best advice is ‘don’t get infected’. Given enough time and the mobility of Americans and, what, the desire to flaunt reality, everyone in time will get infected. There is no reason to believe in long term or strong immunity from having it, nor given the science, history and what is required to make 330million vaccines, that everybody getting infected won’t be the case. It be better for life on earth if that didn’t happen all at once. Given the law of entropy, trying to sustain everything as it and not get infected and treat the sick means life is going to get simpler for everyone. And that is the way it is. Next up Climate heating.