Yves here. This is an important reporting on a natural experiment involving two neighboring communities in Queens, Flushing and Corona. It shows how individual actions make a large difference in coronavirus infection rates. And a telling detail in Flushing, which has a large Chinese population which was tuned into the seriousness of the outbreaks in China, was that even with businesses taking measures to protect workers early, such as mask use for employees and patrons, many still had to shutter in late March because employees were not willing come in.

I also hope readers will bookmark THE CITY and consider making a contribution.

By Ann Choi and Josefa Velasquez, with additional reporting by Christine Chung. Originally published by THE CITY on May 3, 2020

A woman is disinfected after entering a market in Flushing, Queens, during the coronavirus outbreak, April 27, 2020. Photo: Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

On paper, Flushing and Corona, two bordering neighborhoods in Queens, are more alike than different.

Separated by two highways and Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, the working-class neighborhoods have a large share of foreign-born residents. Corona is predominantly Latino, while Flushing is home to a large Asian community.

Both are high-density areas with similar socioeconomic profiles. They’re linked by the usually crowded No. 7 train.

Nearly half of workers in both neighborhoods are employed in food service, construction, cleaning and transportation — jobs that New York State has deemed essential through the pandemic.

Residents of both places typically have household income below the Queens median and a similar share of people who lack health insurance, as measured by the U.S. Census Bureau. And almost half of apartments and houses in both areas have more than one occupant per room, the Census definition of crowded.

Yet when it comes to COVID-19, the differences between the neighborhoods couldn’t be more stark.

Corona emerged as the early epicenter of the outbreak in New York City and shows no sign of slowing down. Meanwhile, the rate of test-confirmed positive cases of the virus among Flushing residents has remained among the lowest in the five boroughs.

Early Measures

The divergent impact of the virus in two similar neighborhoods suggests that low incomes and poor access to health care alone do not predicate the virus’s damage, public health experts say.

The divide between Corona and Flushing also highlights a striking possibility: that early measures many Flushing residents, workers and businesses took to protect themselves — during crucial weeks while city and state government held back — may have made a difference.

“I was very aware when the virus first started in China,” said a Flushing nurse, originally from China, who spoke with THE CITY on the condition of anonymity.

“I knew we’d be hit hard if America didn’t prepare,” she said.

In addition to wearing masks well before Gov. Andrew Cuomo ordered it April 15, she made her husband work from home days before his accounting company required its workers to do so.

In Flushing, locals suspect that early warnings from family and news reports in East Asia, coupled with preventive measures and the shuttering of businesses, lie behind the neighborhood’s low COVID-19 infection rate.

“A lot of Chinese people in New York City were probably more aware of the situation earlier,” said Kezhen Fei, a senior biostatician with PRA Health and Science, a research group.

City data confirms that Asian residents have the lowest rate of non-hospitalized cases.

By mid-March, Crystal, who did not want her last name published, and her 67-year old mother had already gotten into the habit of wearing masks and gloves whenever they left their Flushing apartment.

They had already stocked up on Lysol and had a disinfectant routine. The pair even purchased alcohol to make their own hand sanitizer.

Family in Hong Kong had warned Crystal, 30, and her mother to take the virus seriously. It wasn’t just another flu, they said.

Weeks before city and state officials urged people in public to cover their face and nose to curb the spread of COVID-19, it wasn’t uncommon to walk around Flushing and see people in masks, said Crystal.

“We’ve been wearing masks way before the city told us to do face coverings,” she said.

“A lot of the Asian supermarkets that I went into started requiring people to do it in order to enter the supermarket,” she added.

Then a curious thing happened.

Although New York deems grocery stores are essential businesses, allowing them to stay open during the shutdown, Chinese grocery stores in Flushing closed their doors in late March.

Seeing the destruction COVID-19 was wreaking in China, Flushing grocery store managers were already taking precautions by February to protect employees and shoppers by distributing masks at the front of the store or requiring mask wearing, said Peter Tu, the executive director of the Flushing Chinese Business Association.

Stores installed Plexiglass sheets at cash registers to protect workers from aerated germs.

But that wasn’t enough for workers.

“Because the supermarket is so busy, they have to always come in contact with the customer a lot,” Tu said.

“The supermarkets, they don’t want to close. But their employees — they don’t want to work,” said Tu. “So the owner has no choice but to close because people are scared.”

In unison, roughly 20 Chinese grocery stores closed, as did many restaurants and other businesses since it didn’t make economic sense to stay open. The grocery stores only just began opening back up Wednesday with limited hours, Tu said.

Thursday 4/30, the Flushing community changed somewhat. Supermarkets have reopened from 11 am-5pm for a limited time yesterday. Customers are required to wear masks, gloves, and social distance. With good protection measures, we sow an increase in pedestrians on the street. pic.twitter.com/swFiprnSlH

— Peter Tu (@tu_petertu1117) April 30, 2020

Flushing is slowly going back toward activity levels of pre-COVID days. There are more people on the sidewalks and more cars on the streets, locals said.

‘No Other Choice’

The situation couldn’t be more different, once you cross the Grand Central Parkway into Corona.

Angie, a Queens College sophomore and a Corona native, was startled just last week to see people crowding in Flushing Meadows Corona Park, playing soccer without masks. The city closed playgrounds on April 1, but parks remain open.

She also noticed unusually large numbers of homeless people squatting at an abandoned house on Waldron Street, and a wave of workers coming off their shifts, coughing.

“It’s a shit show,” said Angie, who didn’t want her last name used. “Walking around here has my heart really, really heavy.”

Angie believes that she became sick with the virus around mid-March. She couldn’t taste or smell. She was sweating for days and had difficulty breathing.

Two weeks before she started feeling ill, her grandmother showed similar symptoms. Angie’s grandmother collects bottles and delivers newspapers twice a week.

At work, her grandmother’s boss had tested positive for the virus. But that hasn’t stopped her from working.

“I told her, ‘You can’t be around people that are sick,’ but she just doesn’t listen. She has this debt that she’s trying to pay back. She has no other choice,” Angie said.

People wait on a blocks-long line in Corona, Queens, to collect food from a church. Photo: Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

Working from home or forgoing work is “nearly impossible” for many residents of Corona, who because of their immigration status don’t qualify for food stamps and other forms of federal assistance, said Assemblymember Catalina Cruz, who represents the area.

“If you don’t work, you don’t eat or pay rent. Simple,” Cruz said.

Cruz has been operating a food pantry from her Junction Boulevard office, which distributes 2,200 meals a day.

On Wednesday, the line to her office was 10 blocks long, with no signs of abating, she told THE CITY.

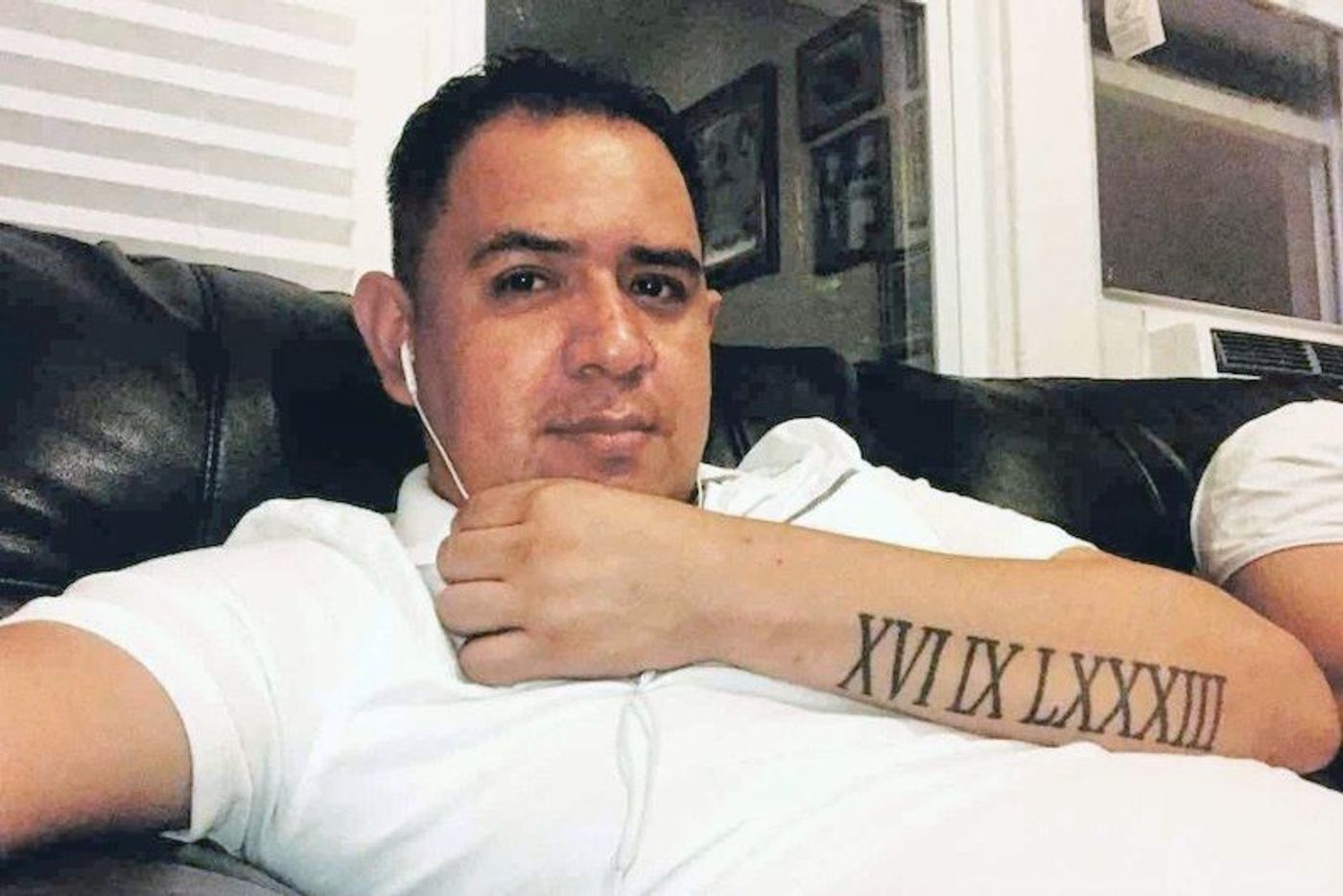

Alfredo Herrera, 36, had only ever lived in Corona since he emigrated from Mexico. He worked at restaurants in Manhattan and cared for his family. He didn’t have children of his own, but is an uncle to 15 nephews and nieces.

Aiderith Sanchez said her uncle was a father figure to her and devoted to his family.

“He would always check up on them because he said that that’s what family was about. Checking on one another,” said Sanchez, 20.

Herrera’s mother visited from Mexico for the first time in late February.

“We threw a big birthday party for her and that was the last day we saw him and he was so happy,” Sanchez said. “Who would’ve thought a month and a half later, he’s gone.”

Infected After Hospital Admission

Herrera went to Flushing Hospital Medical Center in early March over chronic stomach issues and was admitted. The hospital quickly became overwhelmed with COVID patients, so visitors were barred.

A few weeks later, Sanchez received a call from the hospital that Herrera had tested positive for the virus, which the family suspects he contracted during his stay. On April 13, the family was notified that Herrera died.

Flushing Hospital Medical Center did not respond to request for a comment.

“We never got to say goodbye. We never got to see his body. We never got to hear his voice. We just got a phone call saying he’s gone, and that’s it,” Sanchez said.

Alfredo Herrera, 36, died of the coronavirus on April 13. Photo: Courtesy of Herrera Family

A Siena College poll released Monday found that 52% of Latinos in New York know someone who’s died from the virus, more than any other ethnic group.

Angie realizes the pandemic does not impact people and neighborhoods equally. She knows four acquaintances who passed away, and friends who are living in abusive households fearing for their lives. Meanwhile, others from school joke about how they long for a haircut.

“Being a part of two different worlds, that’s hitting me more now,” said Angie.

“I just want my family to live. I don’t want my friends to die.”

A City Divided

Hispanic and black New Yorkers have died of coronavirus at twice the rate than that of whites and Asians, according to the city Department of Health and Mental Hygiene data as of April 30.

COVID-19’s varied spread among neighborhoods and social groups highlights how segregated New York City is, said Bruce Y. Lee, a professor at the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health & Health Policy.

“If you see differences in the spread of infectious disease among different populations, that’s highlighting the differences in social dynamics. If everyone were mixing with each other homogeneously and equally, then you should see relatively comparable infection rates and we’re not seeing that,” Lee said.

Public health experts point to higher rates of the underlying health conditions among black and Latino New Yorkers that make them as a group more susceptible to death or serious illness from the virus.

“What’s happening right now with both Latino and African Americans is a good illustration of the power of the social determinants, economic, environmental and structural determinants of health. Things like poverty levels, access to food — especially healthy food. And right now, for many, many families it’s just food, any kind of food,” said Dr. Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, director of the UC Davis Center for Reducing Health Disparities.

But Asian New Yorkers are not immune to underlying conditions.

Studies show Asians have a higher prevalence of hypertension than Hispanic residents in New York City, the leading health condition coinciding with COVID fatalities — found in 60% of people who died of the virus, according to the state health department.

Black residents had the highest rate of hypertension at 43.5%, followed by Asian (38%), Hispanic (33%) and white residents (27.5%), according to a 2017 U.S. Centers for Disease Control study.

Fei, the author of the study, noted that not getting the virus from the first place is most effective in preventing mortality.

East Asians “were looking into all these strategies early, before the pandemic hit America,” said Fei.

Blaming ‘Density’

As of Thursday, 13,000 city residents were confirmed to have died of COVID — more than in any state in the United States and more than in most countries.

Seeking to explain this extraordinary concentration of fatalities, both Mayor Bill de Blasio and Gov. Andrew Cuomo have both repeatedly cited New York City’s “density.” But places with equal or greater clustering of people have contained the virus’s toll much more successfully than New York City has.

South Korea’s capital city, Seoul — with a 9.1 million population and one of the world’s largest subway systems — has recorded two coronavirus deaths.

San Francisco and other Bay Area counties issued the first shelter-in-place order in the country on March 16, an order that expanded statewide within days. At the time, California had 1,000 confirmed cases.

California reported 1,800 deaths as of Thursday. Meanwhile, New York, which has half the population of California, has 24,000 deaths from the virus — 13 times that of California.

As San Francisco’s policy went into effect, de Blasio contemplated a similar move only to be shot down by Cuomo, who said the mayor didn’t have the authority.

Three days later, after arguing over the semantics, Cuomo announced “New York State on PAUSE,” effectively a shelter-in-place order that started five days after the mayor first floated the idea. By then, New York had confirmed more than 15,000 cases.

For their part, de Blasio and city Health Commissioner Oxiris Barbot spent crucial days in March attempting to reassure New Yorkers to carry on with activities.

“I want to emphasize the risk to New Yorkers of contracting COVID-19 since the beginning has been low,” Barbot testified to the City Council on March 5. “But as we are seeing community transmission, we are really paying very close attention to that. The important thing is for New Yorkers to remain vigilant.”

Asked by Council Speaker Corey Johnson for her current guidance, she said: “We want New Yorkers to use the subway, to go to the theater, to go to gatherings, to go to banquet halls and celebrate life. But we also want New Yorkers to pay attention.”

Even as he urged New Yorkers to avoid physical contact and moved to shut down public gatherings in mid March, de Blasio sent a mixed message by going to the Prospect Park YMCA for a workout.

Asked to comment on the greater toll of the coronavirus in Corona than in Flushing, city Department of Health and Mental Hygiene spokesperson Stephanie Buhle said in a statement: “COVID has disproportionately affected communities of color, particular[ly] Latino and black New Yorkers, exacerbating disparities that have for too long persisted across our city. We are doing everything we can to tackle these disparities head on and remain committed to treating every New Yorker equally.”

This story was originally published by THE CITY, an independent, nonprofit news organization dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.

Nomen omen?

An unfortunate case of nominative determinism…

Why does that apply in this situation?

Please clarify you’re gnomic response.

of course, it should be:

your gnomic response.

The pandenym Corona in the title had me foxed for a moment.

My office is at the edge of what passes for a Chinatown in Dublin, and its very noticeable that the Chinese/Korean community there was far more prepared – they all had stocks of masks in by mid January, and were the first to close down when the country stumbled towards a lockdown (most other businesses waited until they were told explicitly to close their doors). I recall in March doing into a Chinese grocers there and being somewhat embarrassed to realise I was the only person in the entire shop – customers and staff – not wearing a mask.

For another interesting comparison of somewhat dissimilar countries, here is a fairly in depth comparison of Ireland vs Sweden:

What can we learn from Swedens Covid-19 ICU figures?

Cambodia has considerable links to China and Chinese, as well as being in the region geographically, and awareness has been high since January. Many I know here have been amazed to watch Western countries continue doing basically nothing, as if they couldn’t and wouldn’t be affected, while the virus swept through China, then Iran, then Italy, until they woke up to find it had reached them.

I can’t recall where I read it, but years ago I read an account by a French doctor who got his first job in Cambodia and to his surprise found himself appointed the senior medic in charge of dengue fever in one of the main hospitals, despite having little or no background in the disease. He was even more surprised (and he said, embarrassed) when he found that his junior local doctors knew far more about the disease than he did, but deferred to him, as he was a graduate from a famous French university and therefore must, in their worldview, be far more of an expert than any Cambodian. He said he spent a lot of time trying to persuade the local doctors to be less deferential to any authority from the West.

The author of the article says, IMO correctly, that the number of ICU admissions is a better indicator of the state of the epidemics than others (confirmed cases or casualties) and I agree except in the case the healthcare system is overwhelmed as this occurred in the worst days in Madrid with 1700 ICU beds and yet many had to be left without needed care.

Certainly here in Ireland they are using ICU cases as the main indicator of the intensity of the disease outside nursing homes. They are only rarely putting patients on ventilators now.

Man, this is really a tale of two cities, isn’t it? Come to think of it, after reading the differences between these two neighbourhoods, that famous quote from that book seems very apt-

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.”

As we go forward, I think that we will see many more of these comparisons between other neighbourhoods, towns, counties and States. It will be important to tease out what made the differences whether it was leadership, cultural, religious, geography, etc. or whatever. I myself am very curious to know, for example, how the Amish are faring with this pandemic.

I remember, as all my posts begin, having this given.

reinforced by a genuine,human weirdo/hero: Dirk Bogarde, wiki gives a reasonable gloss on such a strange celebrity

The Night Porter – that one stick with me.

My opinion is that the chinese-americans have retained a functioning community via Chinatowns”. Used to ride a city bus through a Chinatown and you can observe that there is a sense of community and civic participation that seems absent or at least less apparent in other neighborhoods. There is more patronage of small neighborhood businesses and less chains. I suspect the children are given more extramural activities and less tv.

I’ve never spent time in an Amish community, but I imagine your mention is very germane because from what I’ve read and seen, a similar source of community prevails there as well.

At the very beginning we thought this was a “Chinese thing”. Info from China passed through the censorship machine might have helped to misguide us into complacency. It could be the case that Chinese residents in Flushing had better insider information.

At the very beginning, maybe.

But by the last week of January? My TV was full of images of the lockdown in Wuhan and so on. Chinese New Year had led hundreds of millions of Chinese to travel around the region and the world. China’s censorship machine completely failed to hide those two key facts, at least from anyone with access to the BBC or CNN. I suspect other reasons for the general Western complacency.

You may realise we are talking here about the not so sophisticated inhabitants in various neighbourhoods in NY (as an example) in countries that have seen in the late decades little in epidemic outbreaks except the flu season. These didn’t have good insight on what was going on in Hubei because of misguiding propaganda was coming from there. Here in Spain, if I see news about, let’s say a flood in New Orleans, I will have the opportunity so have a better idea on the extent of the problem from the personal side, Interviews with people in the epicenter, to the general side (data). A nebulous of propaganda, hidden realities in residential buildings in Wuhan, and difficult to believe data came from Wuhan and the rest of locked China veru much veiling the reality of what was really occurring there. Mistrust on Chinese authorities is on the rise and for good reason.

The Flushing Chinese community was founded by Taiwanese (compare to Manhattan or Sunset Park), and attracts wealthier Mandarin speaking Chinese. There’s a natural counterweight to the messaging and noise coming out of mainland Chinese news sources.

I mean, Taiwan was even faster to react than the CCP.

Not mentioned in the story: The Hispanic culture of touching.

“In social situations, for Hispanics, personal contact is extremely common. Some people joke that for Latinos there is no concept of personal space. Hugs, effusive handshakes, kisses on the cheek and pats on the arm are normal and to be expected during personal interactions, even when the two people have not known each other for very long.”

Five Cultural Differences To Keep In Mind When You Market to Hispanics

That sure makes sense to me. I live in WA state in a county that has a population of around 40,000, 90% being Caucasian. So far we have had only 18 known cases and 1 death, (with very little testing being done as far as I can see). Our county has had around one case per 2000 people.

30 miles away, Yakima county has 250,000 people, of which around 50% are Hispanic, that’s about six times the population of our county. Yakima is the worst county on the west coast for COVID cases, a hot-spot with one case per 130 people, and 60+ deaths. The difference is as stark as it is in Queens.

I actually think that once again the ‘experts’ are lazy and, well, perhaps not all that expert, after all. Reading what these public health experts had to say struck me as kneejerk social justice platitudes. Not to say that there aren’t disparities but the assembled facts would seem to call for a deeper observation — and yet none of them seem to be able to think any deeper than muh racism. Sometimes I wonder if that, in itself, isn’t a kind of soft racism.

I have worked as a health care marketing consultant for over 10 years and I can say with certainty that health care ‘providers’ have been taught that health care ‘access’ is the root of all evil. “If only people had access to healthcare, all would be well!”

While it’s true, it’s a bit of a red herring when it comes to chronic disease, it seems to me. Lifestyle is the primary cause of co-morbidities — obesity, diabetes, etc. — not lack of ‘access to healthcare’. No doctor can ‘fix’ your lifestyle for you. The doctor will prescribe pharma and recommend ‘diet and exercise’.

Being a fat person with high blood pressure, I speak from experience. I know that my lifestyle is the problem. And that’s a much harder problem to fix — as Lambert likes to say “at scale” — than even the thorny problem of ‘access’.

individual choices take place within a matrix of family, cultural, and socioeconomic conditions.

airbrushing out the impact of food deserts on so-called “lifestyle” health issues like obesity, diabetes, and heart disease is disingenuous at best.

the problem with “access” to health care is that it substitutes a fictional egality for the reality that many don’t in fact get needed medical treatment.

this is “hard” racism, among other things.

Perhaps this could be another element: Vitamin D is an essential support for the immune system. Nobody in NYC gets much sun in the winter, but from what I have read, black- and brown-skinned Americans are more likely to be chronically Vitamin D deficient than those with lighter skin tones (darker skin absorbs much less Vit. D from the sun).

Maybe there’s a Vitamin D link in the difference between California and New York state rates of infection as well. Dr. Roger Seheult explains in #59 of his excellent MedCram video series what supplements he takes to support his immune system as he treats Covid-19 patients in the hospital on a daily basis:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NM2A2xNLWR4

This might also help explain why CV never established in New Zealand. It hit in late summer and it is a powerfully sunny country. Only 5% of the population is ‘deficient’ in vit. D and ‘only’ 27% have below the recommended level:

https://www.health.govt.nz/your-health/healthy-living/food-activity-and-sleep/healthy-eating/vitamin-d

I’d imagine the numbers are similar for Australia, which also seems to have dodged the bullet.

It doesn’t explain the difference between Cali and NY, because Oregon’s rate, at the same latitude as NYC, is 1%. We get even less sun in the winter than NY, though this last winter wasn’t typical.

NY does have a lot more dark-skinned people, but doctors here tell everyone to take Vit. D; the sun just isn’t strong enough to do the job.

It might not be very politically correct, but there should be a campaign for dark-skinned people in the north to take D supplements. Milk is the only supplement commonly available now, and a lot of non-Caucasians can’t drink it.

In response to Carla’s point about vitamin D, Dr John Campbell on Youtube has talked about this extensively as well, and he recently described a published study which found that people who had died from Covid-19 within its sampled group were 10x more likely to have been deficient in vitamin D.

The article he referred to is here: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40520-020-01570-8

And Campbell’s explanation of it is here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bga_qG30JyY

Dr. Roger Seheult has many great videos related to the Corvid19 virus. In his video #34 he explains the link between zinc and Chloroquin and how it may effect the virus replication. All his Covid19 videos are extremely informative even though they heavy on biology.

I lived and worked in Flushing a few years back. the one thing that needs to be recognized is that Latino culture is fairly dominate in that area. the sculpture known as the Unisphere is called EL Mundo even by the Asians and we all got by speaking a sort of pidgen spanish.

My point is that the Latino population was energetic and confident. The Asians seemed to feel more vulnerable. Given how close we all lived together, I can’t imagine that the Latino population didn’t have the same info about the virus. We talked a lot. I can, however, see that the Latinos would have felt themselves to be more safe. I also know that the Chinese, in particular, would have been dead on it.