By Jerri-Lynn Scofield, who has worked as a securities lawyer and a derivatives trader. She is currently writing a book about textile artisans.

The COVID-19 pandemic has inflicted widespread damage worldwide: people are suffering from a novel illness, while economies are collapsing as public health authorities sequester us in our homes and shut down social and commercial activity.

Yet widespread lockdowns have also given nature a temporary breather, allowing us to see anew the natural life that surrounds us and reflect on the damage ‘normal life’ inflicts on the environment, as I wrote in, COVID-19 Lockdowns: Birds Singing, Flamingoes Flocking, Dolphins Dancing, Cleaner Air and Water.

Last week saw publication of a new study in the journal Biological Conservation attempting to asses the effect hunting has on biodiversity, by examining data from the migation of shorebirds along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway (EAAF), Extent and potential impact of hunting on migratory shorebirds in the Asia-Pacific.

The previous popular explanation for the declining populations of birds, particularly shorebirds, along the EAAF was habit destruction. Yet the problem has previously received scant systematic scientific attention: the distances covered as these birds migrate are vast, and their migration routes, though differing among species, all nonetheless traverse several countries – many of which have scant resources to devote to scientific study, and the hunting records are poor.

Bird migrations that cross through Europe, and the Americas, are much more closely monitored, and somewhat better understood. One of my favorite things to do when I’m on the east coast of the U.S. at the right time of year is to visit Cape May, New Jersey, during the hawk migrations that occur each autumn and spring. Once the season starts to change, thousands of birds fly overhead. An amazing sight – even if you have think little interest in birds, you might want to try to see this at least once during your lifetime

Conservation of Birds

The U.S. has protected these its migrating birds via statute and treaty, beginning with

Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, implementing a 1916 treaty with Canada, and extending to include further treaties with Mexico (1936), Japan (1972), and Russia (1976). Other statutes conserve necessary habitat is conserved as well, due in part to an uneasy alliance between the hunters who like to shoot waterfowl and the birding community. The hunters form a powerful constituency, attested to by the various presidential candidates who’ve suited up for their duckhunting photo opportunities (such as – are you surprised? I remember this event in real time – Bill Clinton

Asia Ain’t Arkansas

But many parts of Asia have yet to progress to conservation of their migrating birds or their habitat. Even if protective statutes exist they lack necessary resources to enforce them.

Several years ago, whilst attending a textile conference in Kuching, Sarawak, on the north shore of Borneo – e.g.,the Malaysian part – I was invited further south into Kalimantan, – e.g., the Indonesian part- by a Dutch expat priest to judge both a kiddie’s fashion show and a textile exhibition. Whilst visiting, I also learned a bit about orangutan rehabilitation, and a bit more about destruction of the traditional lifestyle of the Dayak people, the original inhabitants of this massive island. Over nightly glasses of tuyak – which we were supposed to be assessing to decide to which samples to award prizes as best in show – the pastor told me about how the rainforest had been destroyed in the decades he’d been living there. Although he nominally attended to the spiritual needs of his flock, this tuyak priest didn’t try to impose his religious beliefs on the people but in fact, was more interested in helping them retain their traditions, in a place where the government was largely concerned with exploiting their resources.

I spent about a month exploring the area, the pastor sending me off on several excursions with trusted local contacts. I rode pillion on the back of a motorbike into ever more remote places, often on roads that traversed palm oil plantations into villages nestled in what rainforest remained.

One thing that struck me was the absence of birds. Now, one thing I know from birding I’ve done elsewhere is that it’s often hard to spot birds in dense rainforest. In deepest darkest Kalimantan, at least in the places I visited, this was partly because there was no conservation ethos: local people shot and killed the birds they could find. I don’t think they did so for for food, but to sell feathers or other parts.

Migratory Shorebird Study

Back to the recent study. As the Guardian tells the story in Endangered shorebirds unsustainably hunted during migrations, records show:

More than 30 shorebird species that fly across oceans each year to visit Australia – including nine that are threatened – are being hunted during their long migrations, according to a study that analysed decades of records from 14 countries.

The study, which experts said filled a major gap in the world’s knowledge about the impact of hunting on declining shorebird numbers, found that more than 17,000 birds from 16 species were likely being killed at just three sites – Pattani Bay in Thailand, West Java in Indonesia and the Yangtze River delta in China.

Prof Richard Fuller, a co-author on the study, said that figure was “terrifying”.

“We know hunting is going on at hundreds of other sites around the flyway. It’s highly likely that unsustainable hunting levels are being executed for many species,” Fuller said.

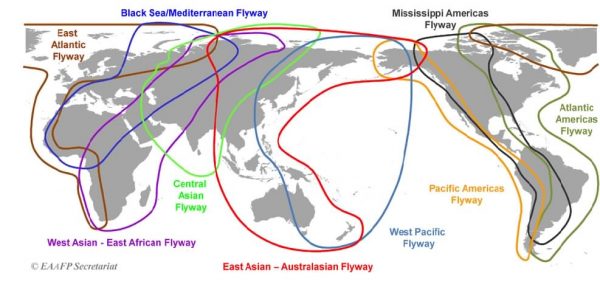

All the birds use the East-Asian-Australasian Flyway – one of nine recognised migratory routes around the globe. Two species – the far eastern curlew and the great knot – are listed as critically endangered under Australia’s environmental law.

The routes that migratory waterbirds traverse on an annual basis are known as ‘flyways.’ This map is largely based on Shorebird routes.

[Jerri-Lynn here: For more information about the flyway, I found the following website a good place to start, EAAF.]

Study Methodology

The Guardian explains how the study was conducted. As with many birding studies, citizen science comes to the fore:

Eduardo Gallo-Cajiao, a researcher at the University of Queensland, coordinated the study, which took five years to complete and appears in the Biological Conservation journal.

More than 100 logbooks, newsletters, citizen science projects, academic studies and “dusty old technical reports” going back to 1970 were gathered from 14 countries.

“We knew since the 1980s that hunting was still going on, but there was an idea that hunting wasn’t really a concern. It has gone under the radar for a long time,” Gallo-Cajiao said.

“Because these birds fly across vast areas, hunting needs to be measured and monitored considering the cumulative levels of hunting at various places throughout the region.

“Up to now, all we had was bits and pieces of data on hunting from different individual sites, but nobody had pooled them together to get a better picture. It was just like assembling a jigsaw puzzle.”

Part of the problem in understanding what is happening to birds migrating along the EAAF is a dearth of hunting records, which are only available for the part of the flyway that traverses Alaska. According to the Guardian:

… the only place where hunting records came from regulated activity was in the Yukon-Kuskokwim delta in Alaska,

Much of the remaining hunting along the flyway – which stretches across 22 countries and Taiwan – was unregulated and likely illegal, [Gallo-Cajiao] said. Some 61 species were being affected, 37 of which were seen on Australian shorelines.

Migrating shorebirds tend to gather in high concentrations to rest and feed as they make their long migrations, making them predictable and easy to hunt.

What Is to Be Done?

Alas, thus far, the only joint action undertaken so far by the numerous countries through which the flyway passes to arrest the decline in numbers of shorebirds is ‘voluntary’, and hasn’t got much beyond the level of identifying the problem. There has so far been a lack of any coordinated monitoring of the birds that pass overhead. Over to the Guardian:

The study found there was a lack of coordinated monitoring along the flyway, despite at least 12 of the 61 species appearing on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s red list of threatened species.

“We need to have a conversation among the many countries in the flyway,” Gallo-Cajiao said.

Two taskforces have been formed to look at hunting impacts – one as part of a voluntary organisation of countries covered by the flyway and another under the UN’s convention on migratory species.

“Hunting is a hidden threat that we’ve known about, but haven’t been able to quantify just how big the problem is,” Fuller said.

From what little I know from observing the hawk migration at Cape May is just how vulnerable birds are during their annual migrations. Many of them are funneled by geography, wind and weather patterns through narrow chokepoints, where they are ‘sitting suck’ for any hunter who hangs out and picks them off. I fear many of these vulnerable species may be wiped out entirely before birds migrating along the EAAF are protected from further slaughter.

And the experts consulted by the Guardian concur:

Prof Richard Kingsford, a UNSW ecologist who coordinates an annual waterbird survey, said: “This study has filled a major gap.

“It’s great that we are getting a handle on this issue, but it’s not a good story. We know these birds are in trouble anyway, so this is a big concern.”

Dr Steve Klose, manager of the migratory shorebird program at BirdLife Australia, said the flyway could be seen like a pipeline and potential “leaks” from hunting had “moved into focus” in the past two years.

“We can see that the flow to Australia is diminishing and we have suspicions that there are holes somewhere. We know populations are going down and we are heading for extinctions,” he said.

Reports like this are heartbreaking. Hard to read them. Part of that Mediterranean Flyway includes Egypt which displays frightful behavior toward migratory birds—trapping, torturing, killing, often for sport. This behavior is a component of Mediterranean culture and pervades Greece, France, etc. Google “lime sticks.”

Indonesia has one of the world’s worst records for habitat- and biodiversity-destruction.

Some Hornbill species are near extinction as people use their bills to make and sell jewelry. Malaysia seems to have a somewhat more defensible approach (not toward palm oil, obviously). When you visited Malaysian Borneo, you may have gone birding on Mount Kinabalu and environs, where birds were plentiful, at least six years ago. Same was true on Langkawi, across the peninsula and in the strait.

Never made it birding to Mount Kinabalu but did one year attend the annual jazz festival at Kota Kinabalu. A treat!

There is plenty of evidence of hunting of migratory birds when they cross the Med via Lampadoza, Malta, Sicily and Italy. it is largely an Italian sport. The hides are valuable and exchange at high prices. No amount of protest seems to affect the extent of the annual cull. The limiting factor has recently been the reduced numbers of birds making the trip.

This post resonates. I suspect there are other causes for the reductions in bird populations in addition to hunting; such as pollutants, habitat destruction, and diminished food sources. Concerning shorebirds, a sense of loss: A pair of osprey nested in a tall nearby fir until a few years ago. That year only one returned in the spring from their annual migration south. Called for its mate for several days before leaving the nesting site, then returned intermittently over the subsequent couple weeks. It returned to the same tree the following spring, again calling to no avail. No other osprey have used the tree for nesting since. This year a pair of eagles spent a couple of hours together there, presumably considering it as a prospective nesting site before moving on. There also don’t seem to be as many songbirds nesting in the arbor vitae as there were some years ago.

But natural life does seem to be benefiting from reduced human activity, and not just the birds. We have heard sea lions in the bay this year, and I read on BBC this morning that the First Nations people in Bella Bella on the BC central coast, entrepot to the Great Bear Rainforest and home of the spirit bear, are self-isolating and barring outside visitors due to the pandemic. Lockdowns are also reportedly helping bees by reducing the detrimental effects of pollutants on their foraging. So the current situation is not entirely without some redeeming aspects. I do hope the recovery of nature is more than temporary.

12,000 acres of wetlands were added to tthe SF Bay a few years ago along the border between Sonoma and Solano Counties.

Access is from Hwy 37.

It was terraformed to provide breeding grounds and this last year saw the first substantial growths of shrubs and groundcovers.

It is wonderful to watch the change and there are many walking paths to enjoy.

Closer to home a pair of bald eagles have taken up residence along the Russian River not half a mile from where I sit, I spotted the nest early Sunday Morning while fishing for trout.

I’m seeing many more ducks and geese along the River this year as well., food for the eagles!

I spent years as part of a Cooper’s Hawk citizen watch group in Alameda, CA. Amazing to watch the same tree house 6 generations of hawks.

I’m also a member of Ducks Unlimited and a couple of other fish and game conservation groups.

And I hunt and fish (when I can which isn’t often).

I can’t abide the destruction of the natural world for profit or vanity.

Hunting isn’t the problem.

Illegal hunting or as we hunters call it, POACHING, is.

Please don’t confuse the two.

Thanks for your comment. You emphasize an important point.

For those under lockdown who are able: This is a good time to make and install bird houses ( or bat, bee, and bug hotels), or to garden in a way that offers support to the creatures that should share our environment. The guests you attract will appreciate your efforts. You can make a difference by setting an example. Everything you do has an impact on the biosphere. Keep it mindful.

Fascinating. It really wouldn’t take much international effort and monetary support to raise this issue in the agenda.