Yves here. As you will see from the article below, the Eurozone has mainly been dithering as national economies burn. The refusal to engage in sufficient fiscal spending, which would have to take place at the Eurozone level, will if anything harden further if Ambrose Evans-Pritchard’s reading on a new German Constitutional court ruling proves to be accurate. From the top of the story:

The German court decision threatens to undermine confidence in the euro and kills off any hope of eurobonds or joint debt issuance

Germany’s top court has fired a cannon shot across the bows of the European Central Bank and accused the European Court of breaching EU treaty law, marking an epic clash of rival judicial supremacy.

In an explosive judgement, the German constitutional court ruled that the ECB had exceeded its legal mandate and “manifestly” breached the principle of proportionality with mass bond purchases, now topping €2.2 trillion and set to rise dramatically. The bank had strayed from the monetary realm into broad economic policy-making.

The court said the German Bundesbank may continue to buy bonds during a three-month transition but must then desist from any further role in the “implementation and execution” of the offending measures, until the ECB can justify its actions and meet the court’s objections.

Ouch.

By Annamaria Simonazz, Professor of Economics, Sapienza University of Rome. Adapted from the author’s presentation in a teleconference organized by the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, April 27, 2020; published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

What Did the European Council Meeting of April 23rd Meeting Achieve?

The answer is – not much. It set up a new Troika – the European Stability Mechanism, SURE (or “Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency”), and the European Investment Bank – providing loans worth 540 billion euros, (of which approximately 54b. for Italy). The size of the “rescue package” is risible even when compared with the Italian effort, which is, in turn, minuscule compared to Germany’s. They are loans, whose conditionality and maturity are kept vague.[1] Moreover, there is a proposal for a Recovery Fund, of which nothing is known. Neither its size, nor its timing, linked to the EU’s upcoming Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), and based on member states’ contributions, to be increased from 1 to 2%. Acute disagreement over the proportion between grants and loans divides the countries’ representatives, often on arguments defined “repulsive” and “senseless” by one participant.

What we have so far seen is mere window dressing. Meeting after meeting, the image that is perceived by a struggling population is of a governing class totally unaware of the dramatic urgency of the situation. In two months nothing came of it, in terms of concrete measures, apart from apologies for the inaction. But, to paraphrase the title of a song by a famous Italian chansonnier: If only I could eat an apology. When, and if, anything does come of it, it will be too little, and dramatically too late. It’s a matter of near-term survival: locked-down firms will not reopen, furloughed workers won’t have jobs to go back to.

In the total absence of the EU, countries are left alone to cope with the disruption of their economies. The huge differences between member states’ fiscal situations mean an enormous difference in their ability to intervene. The data on fiscal measures change rapidly, but according to IMF data as of April 23, direct intervention in Germany corresponded to 4.9% of the GDP[2], compared with 1.4 for Italy and 1.6 for Spain, not to mention the gap in state guarantees for business to access liquidity.

We are left with the European Central Bank (ECB). It has changed its rules to accept as collateral assets with credit ratings below investment grade. It has lifted the self-imposed limits on the share of public securities it is prepared to buy, allowing temporary deviations from the capital key and limits to each issue. Under its old and new programmes (QE and Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme, PEPP, launched on March 8th) in 2020 the ECB could purchase 1.1 trillion euros worth of securities (7% of the Eurozone GDP); 10% of the Italian public debt (€ 160- 180 billion), besides rolling over €350 billion worth of securities.

All well, then? Not really. As stressed by The Economist,[3] the ECB is the outlier among its peers: the Federal Reserve, Bank of Japan and Bank of England are doing much more. And Christine Lagarde pledged to do even more if needed. However, ECB intervention is discretionary. It’s up to the ECB whether to intervene or not, and past experience has shown how its choice can affect economic and political developments in the various countries. “Technical” decisions can affect spreads, agency ratings, refinancing conditions, the sustainability of the debt, and indeed the fate of governments. Threats can thus be very effective, as demonstrated by its handling of Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) in the Irish and Greek crises. Finally, by stalling the crisis, the ECB provides the governments with an excuse for inaction.

These considerations are important to understand the climate in the southern countries and the widespread disillusion with the European dream.

What Are the Merits of the Different Proposals on the Table?

Flimsy as it was, the Recovery Bond proposal had the effect of burying any discussion over alternative solutions (such as Eurobonds or Coronabonds). No consideration was paid to the possibility that, by restoring confidence in the continuity of the EMU projects, a “whatever it takes” from the Eurogroup, and the provision of a safe asset (other than the Bund), might have mobilised domestic savings, thus contributing to alleviate the financing problems in debtor countries. The stance was: no mutualisation, period. Thus, there are no other proposals on the table.

There are several suggestions off the table, though, and they are taking worries over the sustainability of the European project seriously, tackling the issues of size, maturity and conditionality. Academics are by now almost unanimous in favouring some kind of monetization (Galì 2020): issuance of perpetuities (consols) or very long term bonds, backed by the ECB (Giavazzi and Tabellini, 2020), or bought by the ECB in the primary market (De Grauwe 2020), and buried for good in its coffers.

Any proposal has to face the fact that piling loans on stricken countries risks causing a new sovereign debt crisis as well as permanent indentured servitude. Italy is the third largest public bond market in the world. There is a concrete risk of disintegration, and there should be a general interest in avoiding it. Exit from the crisis should be dealt with not as a matter of “solidarity”, but of self-interest. As Münchau (2020) put it: collective action should be seen as “insurance risk” against default.

Intervention is dramatically urgent now, because, as also stressed by the former governor of the Dutch Central Bank, Nout Wellink[4], in a month’s time it will be too late, economically and politically. There is a need for income support for households, and credits and subsidies for businesses, now. Many firms won’t be able to survive anyhow, which means that in the medium term we shall need to intervene again to avoid a new, more severe phase of debt deflation. It seems to me that our EU governors are unaware of just how destructive the current situation is.

What Will the Recovery of the EU Economy Be Like?

It depends. If coping with the crisis is left to national policies, with only the ECB left trying to keep the euro from disintegrating, divergence can only accelerate. Lacking adequate support, struggling businesses in the southern countries will disappear, the destruction of productive capacity will produce cumulative effects on the budget deficits (a disaster film that we had already seen in the previous crisis).

With an even more impoverished South, and international conditions radically changed, it is doubtful that the frugal North will prosper. This is all too clear to many industrial and financial interests in the North (and perhaps also to Mrs. Merkel). The game that we had already seen in the previous crisis, waiting to reach the cliff edge before taking action, is extremely risky in the current situation.

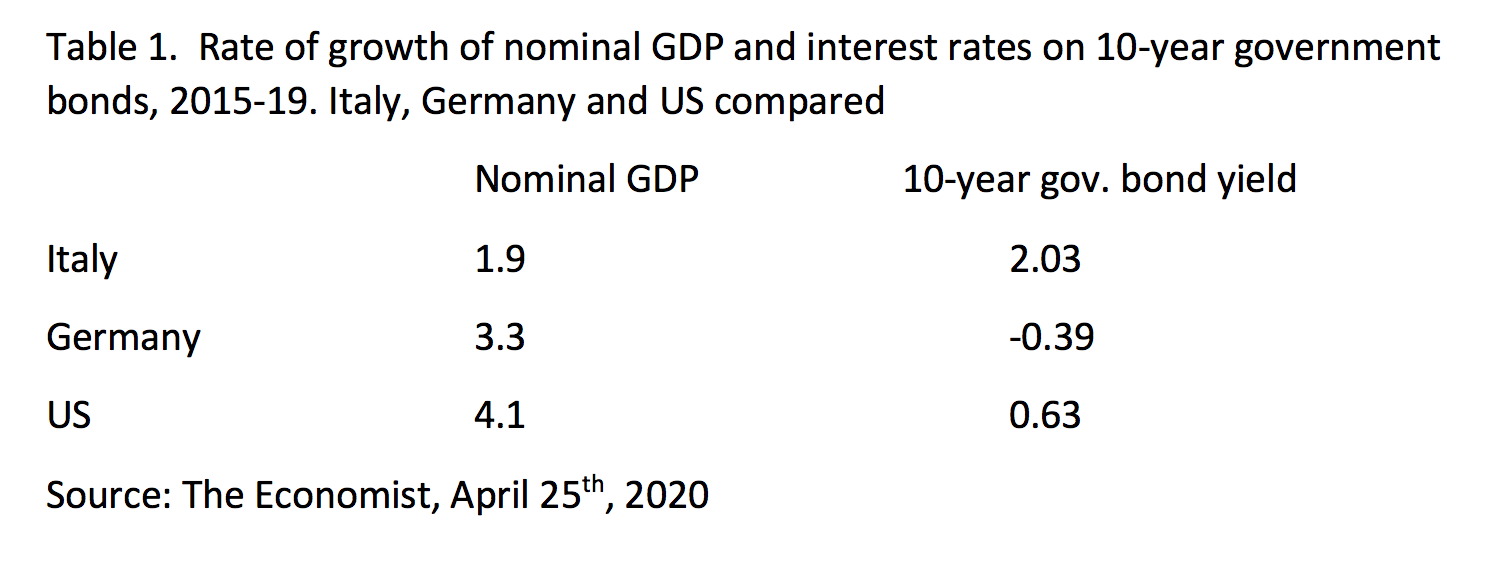

In any case, the solution cannot be returning to the pre-coronavirus situation. Divergence was underway before the pandemic. Structural problems cannot be solved with austerity or market policies (Celi et al 2018). Very long maturities and low interest rates, though necessary, will not help if the GDP growth rate does not increase (table 1). Restoration of the old fiscal rules would hardly go down very well, even with pro-Europe governments since, as Abraham Lincoln put it, “you cannot fool all the people all the time”.

How Concerned Should We Be About the Political Fall-Out from Eurozone Policy Responses?

Europe is now deeply divided. Recrimination is rife in creditor and debtor countries alike, fuelled by many misconceptions. There is a mistaken belief, prevalent in the North, about the spendthrift South. Italy has been running primary surpluses for 30 years, since the 1990s, with the one exception of 2009. It entered the EMU with a huge public debt, but its GDP ratio kept falling slowly to just below 100% immediately before the 2008 crisis. It is true that the rate of tax evasion is high but, on this point, nobody is perfect. We have, within the common market, tax havens[5] and countries competing via subsidies and low wages. And not only do these distortions hit some countries harder than others, but while firms take their profits to and pay their taxes (so to speak) in tax haven countries, it is the countries where they produce that have to disburse the unemployment subsidies in a crisis.

There is another misconception over the refrain: “no more transfers”. When were these transfers made, if we may ask? Greece has been stripped to the bone, first to save French and German banks, and subsequently it was dispossessed of its airports, harbours and firms, bought at bargain prices.

Austerity meant low growth, low wages, cuts in services, increasing and widespread precariousness, and youth migration. It caused impoverishment, greater inequalities, anxiety and popular resentment. The absence of Europe in the various crises – financial and economic in 2008, immigration, coronavirus – has turned the population against the EU.

A change in mind-set is necessary and urgent. And it seems that, in this crisis, more people in the North may be disposed towards a greater degree of solidarity than their governors have been able to perceive. We must act quickly, before things deteriorate to the point of no return.

_____________

[1] Even SURE, a temporary fund of up to €100 billion in total, will provide financial assistance in the form of loans granted on favourable terms from the EU to member states (Vandenbroucke et al., 2020).

[2] In addition to the federal government’s fiscal package, many state governments (Länder) have announced own measures to support their economies, amounting to €48 billion in direct support and €73bn in state-level loan guarantees. (IMF, Policy Responses to COVID-19, https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/…

[3] “Covid-19 and public finances”, The Economist, April 25th 2020.

[4] Oud-president DNB Nout Wellink: Verdubbel noodfonds en maak tempo met maatregelen https://www.nporadio1.nl/binne…

[5] According to Oxfam International (2020), the Netherlands comes third, after Bermuda and the Cayman Islands, in the world’s top corporate tax paradises. Tax avoidance via six EU member states (Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Belgium, Malta, Cyprus) results in a loss of EUR 42.8 billion in tax revenue in the other 22 EU countries. Fiat Chrysler, to name but one, moved its headquarters to Amsterdam in 2014 and, on the basis of special agreements with the Dutch government, it gained tax advantages to the tune of EUR 20-30 million. The EU and the OECD have waged a long, though not particularly effective battle to get the Dutch to change their ways.

See original post for references

The EUR is imo dead in the form it is now. There are only two questions now – when will it die (or transform, to maybe a smaller “germanic” currency union), and whether in the process it will take the EU with it or not.

EUR and/or the EU? As Clive comments below, the most consequential implication of this judgement isn’t so much related to the EZ monetary policy. The ECB has so far indicated it would carry on as before (it “takes note” of the ruling), effectively calling the GCC’s bluff – now it’s going to be up to the Bundesbank to decide where it stands; and even if it chooses to suspend its participation in the ECB programmes, there’s already noises being made about workarounds, namely asking other national CBs to pick up the Bundesbank’s share. The supremacy of the CJEU being openly tested, in rather polemical terms shall we say (the GCC found the European ruling “incomprehensible”), rather than simmering quietly, does seem to represent a challenge to the European Union itself as a rules-bound-and-fudge-augmented construct.

I wish I could read German fluently – I do not know how much support this ruling will have amongst the general German public, as opposed to those who had always opposed the EU/ECB as a violation of German sovereignty and some of what they take as core German interests and/or economic policy principles. My first thought would be that Merkel, cautious and loath to take risks as she is, would have gamed out the potential censure of the GCC beforehand, unless she was moved to let things go ahead as they did out of desperation. It does seem like time is running out for German politicans so inclined to make a persuasive argument that European “solidarity” upholds, rather than undermines, the German national interest. The Greens, SPD, and the more “centrist” fringes of the CDU, if they truly believe that the survival of the EU/euro benefits Germany, must make that clear; no more catering to more sovereigntist opposition while quietly letting the European can-kicking carry on.

Moving across the Oder-Neisse, the Polish Deputy Justice Minister has (to the surprise of few) already made it clear he sees the GCC ruling as validating his government’s prior arguments, ie that interpretation of the legal limits of the European treaties falls to the Member States themselves – not to the CJEU.

Unfortunately, many here don’t really understand that the national central banks including the Bundesbank while existing in a legal sense no longer have the ability to “re-issue” old national currencies without a massive amount of disruption(far beyond Brexit). More than half of the Bundesbank’s critical IT systems are hosted and provided by the ECB and the rest of the Eurosystem. Most of the half that remains internal to the Buba are scheduled to be phased out in just the next two years. None of the NCB’s have printed or designed their own banknotes in over 20 years.

So yes, in theory, the Buba could try to scrounge up some 20 year old computer hardware and OS’s(say hello to Windows 2000 server again) and fire up the old Deutschmark RTGSplus payment system but how many banks in Germany might even have IT the capability to talk to the old RTGSplus software. Also do you want to imagine how many security vulnerabilities might exist in such an old piece of software.

Greece refused to take such steps in the middle of Depression as bad as in the 1930s and even back 8 years ago the NCB’s had more legacy infrastructure left from the national currencies. Today(unlike during the Greek crisis) the ECB is now the pan Eurozone supervisor of all credit institutions so it is not even clear the German government can order banks to prepare to reintroduce a national currency without countermanding the ECB’s bank supervision authority. I just don’t see how Germany as one of the most prosperous states in the world is going to undertake such a chaotic effort just because some obscure academics are offended by the present arrangements.

This is not to say that this state of circumstances is necessarily legitimate or democratic but most “state building” through history hasn’t been either. The Act of Union most historians I think would NOT consider a true democratic merger of equals instead of being PR effort to cloak what was basically an English takeover of Scotland. It is also true in the earliest days of Euro there was some technical and logistical ability for an individual country to back out and the centralization of power towards the ECB away from the NCB’s over the last 20 years while justified on the grounds of efficiency was probably in secret really designed to cutoff any escape route out of the Euro but then again this is the history of most “centralized” institutions. Even in the context of Brexit we don’t really know yet whether it will work and Brexit is far less complex than leaving the Eurozone.

Thank you, illuminating comment!

The German Constitutional Court’s ruling was a slow-burn firework which will put on a more, ahem, colourful display as the years and decades unfold for the EU. For the first time, a Member State has dared to tell the previously untouchable CJEU it can stick its opinions where the sun don’t shine. All, of course, in far more measured judicial terms.

Germany has told the CJEU in no uncertain terms that their previously stated approach whereby the CJEU got to determine the scope of the EU Treaties and their permissibility and interpretability at the edges (and with the law, in our current societies, it always ends up being about what happens at the edges, because everyone is always wanting to push the envelope, even in the supposedly Precautionary Principle EU legal framework) is a bust. The Member States do the determining. For the CJEU to try to make such determinations is judicial overreach.

For reasons which I could never really get my head around, Germany was always far more vexed by the problem of CJEU judicial activism than, say, the U.K. The U.K.’s beef with the EU was always on much more nebulous “sovereignty” concerns. Gluttons for punishment can read this incredibly detailed academic work on the subject. Although couched in bookish — you could even say “Germanic restraint” — terms, the disquiet about how the CJEU advanced its scope is clear in the text.

The result of the German Court’s decision, though, amounts to the same thing as the U.K. expressed much more scruffily and raucously: Germany wants its sovereignty (or some of it) back. It is entitled to it back, because the CJEU picked its constitutionality pockets.

Traditionally, the EU has advanced its integrationist agenda by extending then, eventually, inevitably, overstepping the legally permissible boundaries of its competencies, papering over the cracks as it went, until it couldn’t find strong enough paper any more. Then, it had to resort to Yet Another Bloody Treaty to put the fix in.

That won’t be so easy this time around. Each treaty met with more nationalist opposition in the EU Member States. Largely because each treaty required more and more transfers of national sovereignty. The peoples of the Member States were increasingly reluctant to give their consents (often needing to be asked the same question more than once, as the EU’s treaty adoption process is infamous for, until they coughed up the right answer).

The one needed to sort out the euro / ECB / bailout mess is going to be a doozie. If it turns out to be more than the people of the EU are willing to stomach, then what?

You need to put the German position in context.

Not that long ago it was all about standing on your own two feet in the global economy, apart from bankers who lent on the nanny state crutches of TBTF (just as well for them as we found out in 2008).

Germany carried out the structural reforms necessary to turn it into an exporting powerhouse, but inflicted a lot of pain on its citizens.

“Germany is turning to soft nationalism. People on low incomes are voting against authority because the consensus on equality and justice has broken down. It is the same pattern across Europe,” said Ashoka Mody, a former bail-out chief for the International Monetary Fund in Europe.

Mr Mody said the bottom half of German society has not seen any increase in real incomes in a generation. The Hartz IV reforms in 2003 and 2004 made it easier to fire workers, leading to wage compression as companies threatened to move plants to Eastern Europe.

The reforms pushed seven million people into part-time ‘mini-jobs’ paying €450 (£399) a month. It lead to corrosive “pauperisation”. This remains the case even though the economy is humming and surging exports have pushed the current account surplus to 8.5pc of GDP.”

They have let the infrastructure go into decline; cut pensions, hurting older people in Germany; they have a housing crisis and a problem with homelessness.

Germany doesn’t feel like a rich country to the majority of Germans.

After 2008, the German politicians said the Club-Med countries were in trouble as they hadn’t carried out the structural reforms like Germany, and they should be punished with austerity. The Club-Med nations were lazy, unlike the hard working German people who were always prepared to make the necessary sacrifices

Then EU policymakers changed their minds and decided that richer countries should support poorer countries.

Think of poor German politicians who have been placed in an impossible position.

Making it up as you go along is becoming a problem for neoliberals everywhere, as nothing makes sense to anyone else.

Thank you.

Herr Hartz, Gerd Schroeder’s friend from the board of VW and worse, as per http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/6269113.stm. The pair epitomised capitalism for thee and socialism for me.

Nationalism is not all the same as nationalist. Nationalism, like growing enough food to feed your citizens is good. Nationalist whereby ‘myths’ usual margin of why the country was/is/can be great as in its white people that do all the X – you name it, is bad. I’ve been going to Germany for 40 years and worked at Siemens for a good stretch. I don’t know in 1947 that Germans had committed to becoming an exporting power house, as a pain per se. What was done, was done with the immense help & direction of the USA.

Jared Diamond goes into quite a bit of analysis about Germany in his recent book “Upheaval”. I’m convinced. And I’m not sure the Germans could have been in anymore pain then they were after the War (second). Being diligent is a core German value, so pain doesn’t enter into it. The Germans I know are fine, but under stress they will make your miserable.

Thank you, Yves and commentators above.

In June 2018, the middle in a series of three talks, under Chatham House rules, in the City addressed this issue. Amongst the audience were London-based academics and diplomats from the EU27, including France, Germany and Italy. The ones from these three countries said that the conditions for Brexit existed in their countries and it was not inconceivable that more sophisticated and wilier leaders than, say, Farage, Le Pen and Salvini, Alexander Gauland and Alice Weidel, would emerge to really rock the rotting neo liberal edifice to its foundations. They suggested that the names mentioned were happy to rock the boat and make money from doing so, but had no real interest in getting rid of the meal ticket and doing something for the masses of people suffering. The Italian pair were particularly scathing, but not much more so than their French and German counterparts. What was interesting to British (based) observers was the somewhat public loss of faith in their political elite and the idea of the EU or EU as currently constructed.

Soon after, there was another talk, organised by the same think tank and at the same place. This time about private equity parasites. Another French diplomat turned up. I asked her what brought her there. She replied that French officialdom were getting worried about Macron’s reforms and the company he keeps, so discussions like these provided useful insights into what was going wrong.

Interesting! Have you got a link of some kind?

Further to the Oxfam study quoted above, my TBTF books all trade finance transactions at its Amsterdam branch for tax reasons and often transacts with the local holding company or a special purpose company, often a letter box with little substance.

Tech platforms tend to be traded with in Dublin or Luxembourg. We, along with two much bigger rivals based in NYC and Charlotte, are scaling up operations in Dublin, not just because of Brexit.

No one foresees these arrangements ending any time soon.

Le Monde, which isn’t known for its excitability or its Euro-scepticism, has a story which probably reflects the general reaction of the European elites to the Court’s ruling. The tone is one of measured alarm.

The Court, it said, has “planted a delayed action bomb under the very foundations of the Eurozone.” But it goes on to sound a series of reassuring notes. Essentially, it says, the ECB has three months to explain why its actions were “proportionate” to the risks faced by the Eurozone in 2015. But even if it can’t do so, the famous “sources” close to the ECB think that it will be possible to continue the purchasing programme without involving the Bundesbank, and that the judgement itself is more of a shot across the bows than a serious attempt to affect policy. .

The main worry is clearly one of precedent: there is nothing to stop the Courts of other nations doing the same thing on other subjects, and Guy Verhofstadt has apparently tweeted that if that happens it will be “the beginning of the end.” Poland’s Deputy Justice Minister has apparently been rubbing his hands on the same platform. And of course in Germany the affair is deeply political, because it’s AfD who are behind the challenge, and, as Le Monde points out, their original complaint against Brussels was not related to immigration, but monetary policy.

Bill Mitchell has a long analysis, with quotations, here http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/

Yes, I’d not be remotely concerned about the Constitutional Court in Germany demanding the right to mark the ECB’s homework, rather than letting the craven CJEU give it an unvarying 10 out of 10 and a gold star, plus a pat on the head. The ECB can trot out some wonkish fiction full of tables, graphs and more footnotes than a circus act accordionist who plays instruments with their toes. The Court can (most likely will) say “Mission Accomplished”.

The real fun is in its brazen and public cutting the CJEU down to size. This was, I suspect, the real intention of the judgement they handed down. The Constitutional Court knew exactly what they were doing — saying, unambiguously, “this far, and no further”. And “don’t even think about trying any of that coronabonds crap with us”.

The EU Commission though will simply “nuke” the City of London and people like yourself at the end of the transition period to provide “deterence” toward the Clives of the world and the German Constitutional Court.

Ooh, I’m quaking in my boots (well, slippers to be exact), my hands are trembling such as to make it hard to not spill my cocoa.

I’m still waiting for the EU to implement its much promised (but not yet seen) alternative to LCH at anything like the scale of LCH’s liquidity pool. In fact, it just waved through another Hall Pass in December. And LCH still dominates and is attracting record EU-domain volumes :

Of course, if the Commission really does have the systems, legal and liquidity capabilities to clear $1.2 quadrillion p.a. in swaps, then sure, von der Leyen can happily nuke away. I wish her the best of luck with that.

Oh, and did you miss that the Commission tried to strong-arm Switzerland into submission but the Swiss merely reacted with a resounding “meh”? They lived to tell the tale, so it seems.

I’ve put up with and replied patiently (well, mostly patiently) to all manner of utter twaddle from EU True Believers over the past four years or so. While Leaver’ers were denigrated by Remain for being thick, racist old people, many Remain’ers (you were probably one) simply refused to look at twenty odd years worth of very valid arguments and issues of concern about the EU. Well, that flapping sound you can hear are some very awkward and noisy chickens coming home to roost. You can’t say no one warned you. I know I certainly tried.

BTW, I am not a “Remainer” as you are suggesting nor am I a “leaver” either. I actually can’t be either one as I am not a UK citizen nor have I lived in the UK. I do think that many of the Brits here like yourself seem to have this idea you guys are still the world’s most powerful nation. You don’t seem to realize for example in the case of LCH there are more than a few people in US(Yves is one of them and I can say this from meeting her personally) along with several members of Congress like Carolyn Maloney and Greg Meeks who think the very large portfolio of USD swaps in London should be moved onshore to the US(such as to CME in Chicago). Brexit gives the US a perfect opportunity to gang up with the EU and take down London. US takes the USD swaps business back to Chicago(which the EU has no interest in) and the EU Commission takes the EUR business to Eurex in Frankfurt leaving the LCH with piddly remaining glorious business of GBP swaps.

And before you mention Trump. Trump wouldn’t know what a swap is or what LCH is if it hit him on the head.

You are a Remain’er even if you’re not a U.K. resident. It’s a mentality. It doesn’t require an actual vote.

As for your LCH re-shoring, well, it could happen. Come back to me with legislation timescales, evidence of genuine political will and some big bucks funding.

Otherwise, your entertaining fantasy needs Nancy Pelosi to carry a stone egg into a burning funeral pyre of Donald Trump’s dead body dragging a mad witch doctor (or AOC, if one isn’t available) as a live human sacrifice in with her to give birth to dragon or two introducing into the storyline, to give it some much-needed plausibility.

So I can assume that a “Leaver” is also a “Trumper” even if they are not a US citizen or resident and never voted Trump? As you say it is not a question of whether you actually voted Trump it is the mentality?

The more specific problem LCH has is the Federal Reserve has never liked the fact that LCH does not really come under their control or supervision, unlike the Chicago based CME. Worse for the Brexiteers is Jay Powell and Trump really don’t like each other. So Powell is unlikely to do anything to help the City or Brexit just because Trump wants it. Actually, as a general rule most top level former US Treasury and Fed officials are “remainers” like Hank Paulson, Bernanke, Geithner, Janet Yellen, Larry Summers, Jack Lew etc.

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-05-06/germany-s-constitutional-court-deserves-our-thanks-on-ecb-and-qe?srnd=premium-europe

‘The message from Karlsruhe is that this obfuscation must stop. If you want to save the euro permanently, the judges are saying, write new rules into the European treaties and explain them to your voters. These German judges would be happy to apply them, because they actually love Europe.

But if you’re not ready to have a proper currency union, with joint debt and governance, then at least be honest enough to admit that. In that case, we must have an open and democratic debate about how, gradually and cautiously, to unravel the euro area as it is. This is the fundamental question for Europeans of this generation. The red-robed judges of Karlsruhe deserve our gratitude for trying to force us to confront the choice.’

Exactly! And this is how it should be, the Germans are generally sticklers for rules and protocols and I don’t think that is such a bad thing!

I think this is it and we will notice that the monetary union is impossible to be kept in a widely diverging economic landscape which is now Europe. I don’t know how many realise that separate monetary and fiscal policies is, to say the least, no desirable but i am pretty sure that many know that such a new treaty to save the euro would be impossible given these divergences. May be a breakup into EuroA and EuroB and each country decides what block is more suitable for their interests?

Murphy should instead be writing long form essays on why his fellow citizens prefer Boris over Corbyn instead of piffle like this.

The problem and the solution it would seem is for Brussels to “crush” the Mittelstand and the Sparkassen Public Sector savings banks. If the Mittelstand and Sparkassen want to issue their own monopoly money Deutschmark which no major multinational company or bank will accept let them and watch them fall flat on their face. What is funny is the Sparkassen cry about margin compression for the ECB’s low rates but they don’t have the courage the raise their lending rates on their prized and loyal Mittlestand customers as despite their supposed loyalty to the pubic sector banking system they are afraid they will take their business someplace else.

The other thing I note is these rulings always seem to cause the Euro to drop against other currencies making German exports cheaper outside of Europe but never actually breakup the Euro. There is a bit of punch and Judy show quality to all this.

I’m puzzled by your post. Wth are you talking about?

‘The problem and the solution it would seem is for Brussels to “crush” the Mittelstand and the Sparkassen Public Sector savings banks.’

-> Why and what does this mean? How would it help the eurozone to ‘crush’ the german Sparkassen?

‘If the Mittelstand and Sparkassen want to issue their own monopoly money Deutschmark…’

-> Parallel currencies are illegal in the eurozone. So, what’s the point?

‘the Sparkassen…don’t have the courage the raise their lending rates on their prized and loyal Mittlestand customers’

-> How do you come up with that?

First, what’s with the ‘loyal Mittelstand”? If the main customer base of the Sparkassen are middle-class, where do lower class citizens go to?

The Sparkassen are also the go-to Banks for people with low-income because they have bank branches in nearly every town. They are reachable on foot or by bike. Ideal for people, that don’t have a car or are not handy with a computer, etc.

So, what I would consider as factual is, that Sparkassen are popular with people up to middle class.

Additionally, the middle class isn’t particular loyal with regard to their banks. Germans in general are traditionally hesitant to switch to another bank, although it changed over generations.

And what’s with ‘…raise their lending rates..’? Whoop dee doo, we got the solution: We just raise lending rates! *Padding each others backs*.

If that would work, why don’t all banks raise interest rates on their loans?

Why? When you need a 5-6 digit loan, you pick the bank that offers the lowest interest rate

because even small differences in interest rate will lead to a significant difference in the principal amount. The competition will keep the rates down and Sparkassen customers wouldn’t make a loan a their bank branch.

So, your comment consists of points that are mostly irrelevant to the topic of the article, aren’t backed up at all by anything resembling a ‘fact’ and don’t even sound plausible.

Doesn’t that seem a little like ‘making shit up’?

I would expect the ECJ would strike that down. The EU will not suffer to have every member state’s courts challenge greater macro-level fiscal harmonisation. Bonds are entirely in their remit in that bonds control rates and price stability. Recalcitrant states like Germany may be allowed some sort of discount or a voluntary participation portion, but there will a minimum involvement across the board. Germany also needs to be reminded that its spectacular wealth accrual is in no small part due to the stability of the EU and EUR which facilitated the investment of their hot surplus into their cheap high-yield neighbours.

When she writes “governor”, she means “government”. In this context, “governor” could only mean a manager at a central bank, which makes no sense.