It’s not a popular position to point out that a particular financial risk is overblown. But when everyone in Corporate America and investor-land is in “Where’s my bailout?” mode, the usual motivations are reversed. Normally, “Nothing to see here, move along” is the default position when the great unwashed public worries about too much leverage, opacity, and tricky practices. But when central banks are doling out trillions, sounding alarms, whether warranted or not, is the way to get someone else to eat the risks you took for fun and profit. And as we’ll demonstrate, the Financial Times looks to have become an unwitting tool of CLO (collateralized loan obligation) investors who haven’t yet gotten their Fed handout.

The article in question is headlined: CLOs: ground zero for the next stage of the financial crisis? The headline and the breathless tone set the reader up for the idea that these complex structures will blow up the financial system, just the way their cousins, collateralized debt obligations, did in the financial crisis.

But as we’ll explain, the absolute size of the CLO market, and banks’ not-much exposure to the risky parts of it, means that absent fraud (or a systemically important bank and wobbly bank having gotten high and binged, and the pink paper and others would likely have gotten wind of that by now), there’s no risk to the banking system. And in the hoary old days of the crisis just past and its predecessors, that was the justification for throwing official money in big volumes to clean up bad lending decisions: that as much as it would seem proper to let incompetent institutions go tits up, letting banks fail tends to engulf even healthy banks, since no one can tell from the outside very well how solvent a particular institution is, and hurts innocents like depositors (even with deposit insurance, it is pretty much impossible for a business of any size not to have way above the guaranteed amount in its accounts regularly, if nothing else when it issues payroll).

So what the Financial Times piece is effectively getting worked out about is that some investors will lose money. Newflash! Investing involves risk! Who’d have thunk it!

In other words, this Financial Times piece is implicitly selling the idea that the consequences of some deep pockets taking hits is just oh-too-dangerous. This is Greenspan put thinking on steroids. And sadly, it seems to be treated as a reasonable line of thinking. Wealth must be spared. The hell with those who live from labor income.

What CLOs Are and Why Comparisons to CDOs Are Spurious

By way of background, a pet peeve of ours is that the financial crisis is widely depicted as a housing crisis when it was in fact a derivatives crisis. If we had merely had subprime and Alt-A loans go bust, the result would have been on the order of the S&L crisis plus maybe another 50%. Bad but nothing like the seize up of the global financial markets that took place in September 2008.

As we explained long-form in ECONNED, collateralized debt obligations consisting substantially of the risky tranches of subprime mortgage bonds (the BBB and BBB- layers) dressed up the part of of subprime securitizations that no one wanted to buy. The top tranches of those CDOs, comprising 60+% of par value, were rated AAA.

But even that wasn’t sufficient to blow up the global financial system. Demand by subprime shorts and banks seeking protection for the loans they were advancing to the likes of subprime lenders like New Century and IndyMac led to the use of substantially synthetic (made mainly of credit default swaps rather than tranches of actual bonds with actual mortgage loans behind them) as a way to generate artificially cheap insurance on the riskiest rated layer of subprime debt. Those derivate exposure have been estimated at 4-6X the real economy exposures. The reason the financial system blew up is that the side bets were a significant multiple of real economy activity, and the parties on the wrong side of those wagers were systemically important, highly leveraged players like AIG, the monolines, Eurobanks, Citigroup, and Merrill.

It is also important to remember the base line. Banks have repeatedly managed to blow themselves up in entirely conventional ways, with good old fashioned loans. Remember the Latin American debt crisis? The commodities bust of the early 1990s, which crated energy and real estate lenders in the oil patch? The afore-mentioned S&L crisis? The not as well publicized LBO loan crisis of the late 1980s and early 1990s? Oh, and how about one of the mothers of bad lending, the Japanese commercial (and to a lesser degree residential) real estate bubble and bust?

Now let’s look at CLOs. They are intrinsically less risky than asset-backed-securities CDOs, which the press took to calling just “CDOs”.

Those CDOs were resecuritizations. They were created from the riskiest parts of mortgage securitizations made of risky loans, as in subprime or Alt-As. Those tranches usually represented only 3% of the entire deal. They’d be worth 100% if the losses on the subprime RMBS were 8% or less, and totally wiped out if the losses were higher than 11%. Since subprime losses averaged more like 40%, nearly all these CDOs were complete wipeouts.

By contrast CLOs are made from risky corporate loans, so-called “leveraged loans” typically made when a private equity firm is buying a portfolio company. So they are more analogous to a subprime RMBS (residential mortgage backed securitization) in terms of the risk level of the assets.1 Note that even with the high level of subprime losses, AAA tranches of RMBS lost only 0.42% on average.

Even though there was a tidal wave of risky “leveraged loans” to fund deals at sky-high prices right before the last crisis, and a lot of them wound up in CLOs, while their value traded down afterwards there were no losses. Admittedly, the Fed dropping interest rates and manipulating long-term rates lower allowed many of the pre-crisis loans to be refied at lower rates. But the Fed didn’t engage in measure intended to rescue corporate borrowers; they were just lucky beneficiaries.

Nevertheless, CLO structures have been made more conservative since the last crisis. See here for geeky details.

But with the bottom dropping out of the entire economy, a lot of former sure-looking bets won’t work out so well.

But should we even care about CLOs? First, the market isn’t all that large. S&P in early 2020 pegged it at $675 billion. By contrast, the subprime market, depending on whether or not you included Alt-As, was estimated back in the day at $1.3 trillion to a bit over $2 trillion. And US GDP was $14.5 trillion in 2007 versus $21 trillion in 2019. Using Pimco’s forecast of 5% contraction for the full year, you still get roughly $20 trillion, showing that the relative importance of subprime lending has fallen even further. And that’s before you factor in the way that credit default swaps greatly magnified the real economy exposures and concentrated them at systemically important, fragile players.

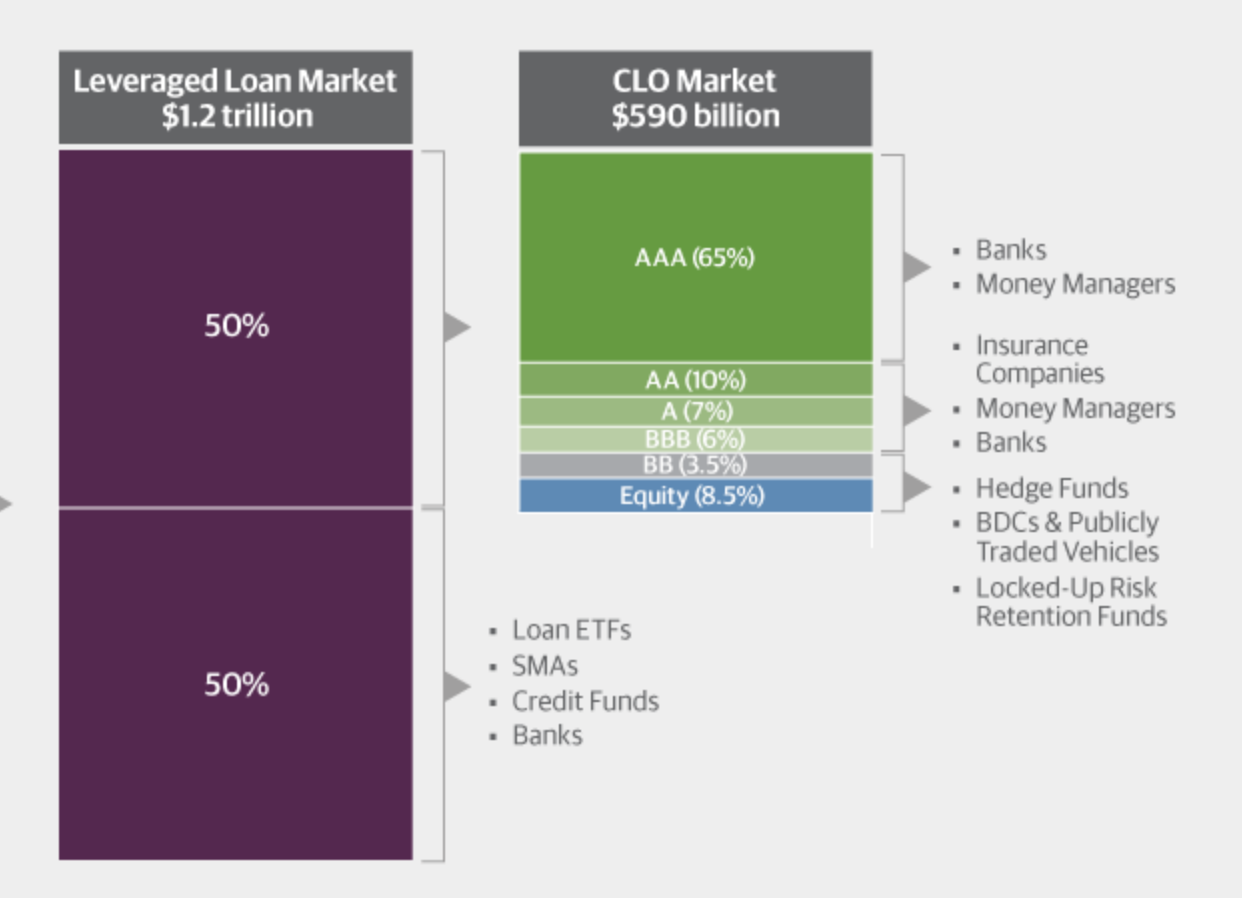

This chart from Guggenheim Investors is a little dated, since it shows a smaller CLO market size but it gives a good idea of who buys what:

The key bit: what do banks own? They are the ones that have to be saved even when they do really dumb things; the other players are supposed to be savvy investors who can take losses.

You can see that banks are the big owners of the AAA tranches, which have shown over time to have enough loss protection that you’ll get all your money. And they are listed third as owners of other investment grade tranches, which means they are less important players than insurers and money managers.

More detail from S&P in March 2020:

CLO holdings at U.S. banks increased by roughly 12% in 2019, to $99.5 billion, with a number of banks growing their CLO securities exposure by double-digit rates, according to year-end filings with the Federal Reserve….

What is perhaps most striking about the results is the high degree of concentration of CLO debt inside the three banking entities, relative to the rest of the banking sector. At $80.2 billion, the three largest holders make up nearly 81% of all U.S. bank CLO holdings.

However, the size of CLO holdings as a percentage of the top-three banks’ investment portfolios is relatively small. For JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, and Citigroup, CLOs as a percentage of total securities on book are 7.5%, 6.9%, and 6.0%, according to Y-9C data.

Now, at just under $100 billion, total U.S. bank exposure represents roughly 15% of the $675 billion CLO market. Assuming that U.S. CLO AAA supply is around $400 billion and that most of U.S. bank CLO holdings are AAA, then U.S. banks can be said to hold roughly 25% of all AAA supply, according to researchers from Wells Fargo.

Japanese banks can also be expected to hold near the same amount, or around 25% of the total AAA supply of U.S. CLOs, according to Wells Fargo.

So who is at risk? Apparently the equity tranche, the bottom 8.5% in the chart above:

Waterfall of payments in CLOs, via Morgan Stanley, which estimates that 85% of outstanding CLOs in the U.S. may fail their junior over-collateralization (OC) tests as leveraged loans default. pic.twitter.com/cx2GFlAXL5

— Tracy Alloway (@tracyalloway) May 7, 2020

To translate: securitizations have risk buffers in the form of overcollateralization and excess spread. “Overcollateralization” results from the fact that the loans in a securitization have a higher principal amount that than the total par amount of all the tranches. Say $100 of loans have $103 of loans. The $3 is the overcollateralization and the CLO documents describe who gets how much benefit from it.2

What the tweet is saying is that the losses on the loans look like they’ll get to be high enough that the equity layer in some (many? most?) CLOs will stop getting interest payments. But again, why should we care? If all the equity tranches stop paying out, that was shy of $60 billion in par value. And it’s not a total bust since they got payments in full before their investment crapped out. And the owners are primarily hedge funds. This is just not worth getting lathered up about, particularly in comparison to all the other exploding loss-bombs.

Likely Reason for the Financial Times’ Hyperventilating

Despite being a “Long Read,” meaning it presents itself as having more reporting behind it than a typical story, it’s remarkable to see the Financial Times duck the real story, private equity leverage, which predictably leads lots of lenders holding the bag at the end of every financial cycle.

And the article also sidesteps another key question: did CLOs make the situation worse than the old-fasioned approach of syndicating leveraged loans (which foreign banks took down in size in the first LBO wave in the 1980s)? Quite honestly, I suspect you can argue it both ways. On the one hand, unless the benefit of CLO risk slicing and dicing went entirely to the sponsors and packagers (possible), investors presumably were willing to accept lower interest rates to get more finely tuned risk exposures. That would somewhat lower the cost of private equity lending, but it’s not clear that this made anything more than a marginal difference.3

On the other, CLOs per the discussion above really did move a lot of the risky exposures out of the hands of usually self-destructive banks and over to investors who bill themselves as sophisticated and able to take risk.

The Financial Times account does provide market size (using JP Morgan data, which gives a slightly higher level that S&P did), albeit a bit of the way into the piece, but no distribution of exposures by rating or who the various investors are. And before the authors get to that, they hand wring over a debt restructuring of medical staffing company Envision Health. As vlade pointed out by e-mail:

The headline is fearmongering and a lot of comments lapped it up.

Thinking about it, the picking of the health company and saying how it’s going to suffer is also there, implying “if you don’t bail out the debt, look at how bad things will happen.”

Vlade is not exaggerating. The article waves the “saving us from coronavirus” flag:

In the midst of a global pandemic, emergency rooms across the US have fallen strangely quiet as patients with other illnesses have stayed away for fear of contracting Covid-19. As a result, one of the surprising corporate casualties of the coronavirus crisis could be some of the companies that provide staff for hospitals.

Envision, one of the largest medical staffing companies, completed a restructuring of its roughly $7bn of debt this month as it moved to stave off bankruptcy.

US readers of this site know better than to see Envision as a good actor. As we’ve written several times, based on the gumshoe work of private equity expert Eileen Appelbaum, KKR-owned Envision and Blackstone’s Team Health have been lead players in the “surprise billing” and other price gouging schemes. The fact that Congress and some states have been working on legislation to end surprise billing is why Envision’s bonds are in trouble. And that reaction also shows how important the fleecing is to the company’s bottom line.

In fact, one has to wonder if the Envision staffing cuts mentioned later in the piece are a shot across legislators’ bows: “Nice ERs you have. Shame if something were to happen to them.”

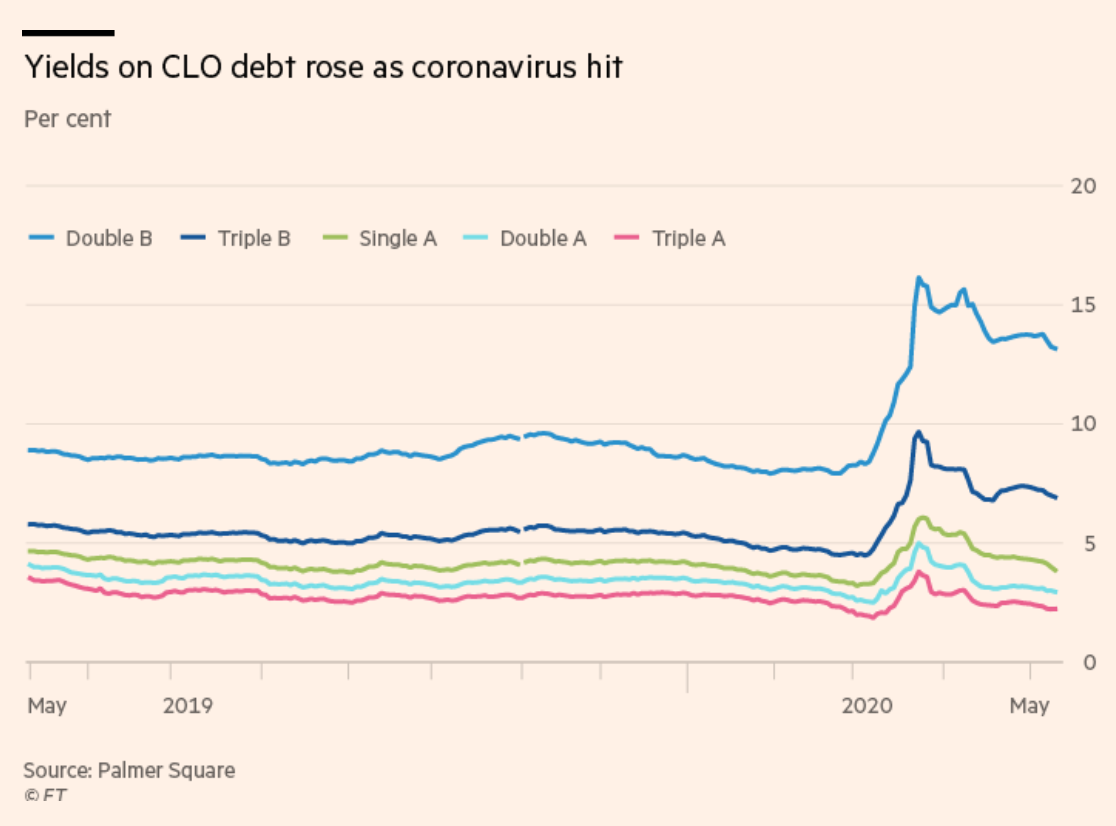

This chart also serves to exaggerate how bad things are:

The viewer’s eye naturally goes to the top line, for the BB tranches the yields have risen the most. Those BB instruments are a mere 3-4% of the total value of the CLO market! They are rounding error. By contrast, the AAA tranches are yielding pretty much what they did in later 2019. Yes, they aren’t trading the same as other AAA instruments, but seasoned structured credit investors ought to know that these AAA creations can and often do trade down in crises, unlike Treasuries and government guaranteed credits.

Moreover, eyeballing the charts, yields have improved since mid-late April, meaning investors are less edgy, when even then, Reuters reported that new CLO deals were getting done on reasonable terms. From an April 22 story:

There has been US $39.4bn of US CLOs arranged this year through April 19, inline with the US$38.7bn sold during the same period last year, according to the data from LPC, a unit of Refinitiv. A record US$128.1bn of US CLOs was arranged in 2018.

US CLO issuance this year has been challenged as spreads on Triple A tranches, the largest and most senior piece of the funds, have continued to widen, hitting an average of 136.2bp in March, slightly tighter than the more than two-year wide of 138bp in February, according to the data. The wide spreads can cut into returns paid to equity holders, who are paid last after all other debtholders receive their distributions, and may cut into overall issuance.

“Spread levels on US CLOs still look relatively attractive compared to other securitized products and corporates,” Collin Chan, a CLO strategist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, said in an email…

“Although the arbitrage for new-issue deals has compressed, (CLOs) are still getting done because equity investors still find the levels acceptable,” Chan said. “Insofar that we do not see significant spread tightening in the loan market while CLO spreads stay wide, dealflow could certainly continue.”

Now as the Financial Times article points out, some CLOs are more wobbly:

More than 100 CLOs were failing at least one trigger brought on by escalating triple C loans, according to April data compiled by Barclays, with 40 failing tests for their triple B rated tranche or higher — debt that is regarded as investment grade. Twelve have also failed tests up to the double-A rated tranche, according to BofA.

It’s hard to know how significant this is without having dollar values. The Financial Times also warns that one-third of the BBB tranches are on review for a downgrade, but again, I find it hard to be sympathetic. If you bought BBB paper, you knew there was decent risk it would decay into junk. However some of these bonds are held by life insurers, who are restricted in how much they hold in non-rated/non-investment grade assets. They usually max out that bucket with real estate. So if their BBBs get downgraded, they’d probably have to sell.

So why all this unseemly whining? The most obvious explanation is that the Fed isn’t doing much for CLOs. One has to wonder if money men have been playing up how bad things supposedly are to get more rescue money. From the Wall Street Journal on April 22:

The Federal Reserve will lend $2.3 trillion to support the economy…The Fed excluded some securities tied to corporate loans and commercial real estate that were among the newest, fastest-growing segments of the bond markets…

The [$100 billion] TALF program won’t include the vast majority of a popular structured security known as a collateralized loan obligation, which is made up of corporate debt generally used to finance buyouts. The program does include so-called static CLOs which don’t allow for reinvestment of loan proceeds, but those account for only a small share of the market. The vast majority of CLOs allow such reinvestment and aren’t included.

The central bank threw some small additional bones to the CLO market earlier this week, but still left most CLOs ineligible. From Bloomberg:

The Federal Reserve revised its Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility to allow CLOs that hold a broader range of leveraged loans to be used as collateral.

The Fed will now accept new AAA CLOs with leveraged loans, including refinanced loans, that priced as far back as January 2019, according to a statement Tuesday on the central bank’s website. Previously, eligible collateralized loan obligations could only hold newly-originated loans….

Yet the changes will only go so far, market watchers say. The terms still require eligible CLOs be static vehicles wherein managers can’t actively trade the loans underpinning the deals, a structure that makes up only a small portion of the market.

It is really a shame to see what has happened to the Financial Times. It was the only major media outlet before the crisis where quite a few writers, particularly Gillian Tett but also John Authers, Martin Wolf, and John Dizard, saw that risk was being underprices across all credit markets and sent clear warnings that things could end very badly, when the US financial press was uniformly in la-la land.

Since the crisis, the paper has gone firmly neoliberal, and perhaps due to the lack of time to do reporting on top of being now the US editor, Tett veers from doing extremely insightful pieces reminiscent of her glory days as capital markets reporter, to doing far too many articles that have all the hallmarks of her having spent too much time with people talking their book. Similarly, this CLO article does show the authors did a lot of legwork, yet somehow missed or chose not to address the most important questions.

_____

1 And remember, at least so far, we don’t have evidence of widespread lending fraud, a big feature of the subprime mania. However, a key difference is that with mortgage-backed securities, the mortgages are transferred through several intermediaries to a trust and they stay there. Certificates are then sold that represent the rights to interest and principal payments made to that trust. With CLOs and CDOs, they can be “static” meaning the loans (or RMBS tranches) are set at the get-go and don’t change, or “active,” meaning a manager can trade assets in and out from time to time, subject to overall restrictions. Most CLOs are active.

2 I haven’t seen any actual CLO documents, so some of my interpretations from CDOs and RMBs may be a bit wide of the mark. RMBS had distinct waterfalls for principal and interest payments. This chart covers only interest payments. It doesn’t mention that the deals almost certainly had “excess spread”, meaning that loans that paid, say, an average of 7.5% across the CLO would have total interest payments of only 7.2% across all CLO tranches. This chart presupposes that the excess spread is already gone and required interest payments are at risk, so the equity tranche takes the hit first.

The article does have good detail on this issue. Basically, downgrades of loans are producing breaches of collateral quality tests, and that looks set to cut interest payments to the equity layer:

Typically, CLOs are permitted under their own rules to hold up to 7.5 per cent of their assets in triple C rated debt. If they stay within this threshold then managers of the CLOs can treat the loans they own as if they are worth 100 cents on the dollar.

This is because when a CLO is created, the underlying portfolio of loans is larger than managers need to pay off debt investors. This is known as over-collateralisation. So long as the number of loans that are near to defaulting remains below the 7.5 per cent threshold, the portfolio is treated as though there will be enough money left at the end to pay investors.

However, if a CLO exceeds its triple C bucket, as many now have, then the lowest priced loans above the threshold are required to be valued at a market price. In a crisis, with loan prices having fallen sharply, this lowers the overall value of the portfolio of loans reported by the CLO. That in turn can impact how investors are paid.

If the value of excess collateral slips by more than a few percentage points, managers typically first cut off 50 per cent of any interest payments on the underlying loans that would have gone to equity holders and use it to buy more loans, with the aim of increasing the value of the portfolio and correcting the breach.

If the value of the underlying loans falls further, then all money is cut off to equity investors. That money is used not only to pay interest to debt investors but to start paying back the principal of the debt, beginning with the triple A rated bonds.

3 Even if private equity firms could achieve somewhat higher leverage levels, that’s not a big bennie. Private equity has for many years been sitting on tons of “dry powder,” meaning uncalled capital. So their equity isn’t a scarce commodity. Thus the gain is a marginal decrease in interest charges. Helpful but hard to see as significant.

The article is actually fascinating case of journalism.

It’s obvious it’s a reasonably well researched and all, but the main conclusions (CLOs will kill us all, and securitised products per se are nuke equivalents) it draws (which are actually not spelled out in the article as explicitly as in the headline) are just nothingburgers when it could have been a great article on the PE leverage and how it makes the current economic crisis worse.

One has to wonder whether the authors are dumb (unlikely, as the article has a lot of detail), naive, or actively shilling for the investors (remember, FT is now owned by Nikkei, and largest CLO holder is a Japanese bank) or some combination.

Thank you, Vlade.

I know some of the FT’s journalists. From conversations with them over the past dozen years, your final phrase is spot on.

Shilling is probably the main cause. Why? Some of the younger journalists see colleagues like Martin Wolf, Gillian Tett and Rana Foroohar on the celebrity circuit, appearing on talk shows and at Davos and getting commissions from publishers. They wish to join these circles, but financial institutions and other investors are gatekeepers, so they must cooperate.

If they can’t join that celebrity circuit, they can advise governments and lecture at Harvard like Camilla Cavendish, who never stops bragging about being responsible for the UK’s sugar tax and wagging her upper middle class finger at us plebs, or they can head public affairs at big corporations or act as public relations advisers to oligarchs.

There are two classes of journalists at the FT. It does feel class based. There are the reporters on the daily output, e.g. the banking team, and the weekly shills like Simon Kuper, Robert Shrimsley and Jim Pickard.

Editorial control is more tightly exercised by Nikkei as time goes on.

Do you remember the FT’s expose of the Presidents’ Club a few years ago? That gathering had been going on for thirty years and was an open secret. In order to show its right on credentials and target a new readership, the FT deployed a dozen plus hacks, well, hackettes, to infiltrate the gathering.

I’d add another class to the FT journous – FT Alphaville. For me, FTA is the only part of FT worth reading. Paradoxically, it’s the only one that’s free.

As a regular reader of FT Alphaville and a subscriber to FT itself, I have to agree with Ives’ and vlade’s observations on what once was a reasonable mainstream paper. They have drunk the kool-aid.

But don’t give up totally on the comments, there’re plenty of ankle biters out there.

So I will put my quibbling hat on, and I should prophylactic-ally note I pretty much agree with everything you wrote subject to a couple of caveats.

I wrote something up as a consultancy exercise on this early last year, which is why I am under the misapprehension that I know a little about it. Also I know Mr. Rosner has been all over this subject for a year, at least! Indeed definitely longer. Indeed Mr. Rosner has been warning about the risks associated with this, and the BDC-type lending for quite some time! But that is his “victory lap” to take.

1) BoE estimated global leveraged loan market as being around $3.2bn. They would have agreed with Guggenheim about around 45%-50% of that market being CLOs. So its probably a bigger market than S&P estimated. I think the BIS suggested $2.4bn for LL and once again about 50% of that being CLOs. I suspect S&P were looking at only North America. But I would still have guessed that $600bn number is too small. Europe?

2) Lobbying for free money! Yup, thats exactly why you hire financial PRs. If everyone else is getting bailed out then, the Fin PRs need to show they are doing something. Call Tracey Alloway! I am told the trade groups in DC are lobbying like crazy on behalf of the shadow banks too! MBS REITS etc.

3) Totally agree re private equity being behind the push to rescue these guys. Personally, I think they do have a nasty problem. The underlying leveraged loans need to eventually be refinanced. If you deplete the pool of equity in the deals you will struggle to find more. The CLOs will enter run-off mode and will not participate in new financings. That will happen around 7.5% CCC content. The PE guys desperate need the CLOs to remain alive. In this kind of structured credit, a shortage of any type of credit, either equity, mezz or one of the higher credit tranches will kill new or rollover deals. So if you want to prevent a cascading series of defaults resulting in pretty much ALL CLOs going into runoff mode, then you need the Fed to step in.

4) Vlade is right. Japan in the form of Norinchukin or Japan Post own about 10% of all the AAA tranches. The FSA did a review and suggested they lighten up a while back. Last time i looked they had been doing so the glacial way, by allowing maturities to slowly reduce their position.

It looks a lot like a death spiral too me.

All that said, I have a very tiny violin in my hands. While I dont blame our PE overlords for trying to steal more money from the tax payers, I dont know why the tax payer should play ball. Apologies for the inevitable typos and forgive if I have misunderstood or misreported myself.

I think the whole CLO market is around 1trln (give or take a few hundred bln). So still a small fraction of say junk bonds market, or even RMBS market.

The important thing is as Yves notes, in 2008 the RMBS market was overlaid by massive derivative positions. I’m not aware of the CLO derivative market being there much. I know that 15 years ago you had a lot of synthetic CLOs, but those went out of favour as the CDS market liquidity (and especially CDS on leveraged loans) evaporated. They did start coming back a bit, not still nowhwere near the glory days of 2005-6.

Anything with a substantial leverage will kill the financial system. Conversely, only a few things that are not levered will.

My worry on EU banks are actually covered bonds. If the EU RE market tanks, it would kill covered bond markets where they often require 80 or better LTV in the pool. And covered bonds are a crucial funding vehicle for a lot of EU banks, so the states would have to step in (if they were allowed to).

Thank you, Vlade.

I agree with you about covered bonds, hence their prudential treatment being less expensive under the EU’s Capital Requirements Directive IV.

Yes, I agree all your points. FWLTW of course!

Harry, Foster Wheeler Ltd? I must have misunderstood something here.

Thank you, Harry.

Working for two of the scummiest originators, I know well about the two Japanese banks you name. For some reason, they allow another Japanese securities house to advise them into this abyss.

Its not much fun being an investor these days. What exactly are you gonna buy?

A fortiori for Japanese real money!

Because interest rates should be indicative of risk – at least I think that is how it used to work – then no bail for investors as all risk can have loss and total loss at that.

The reason the last crisis was so bad in 2008 was, in my opinion and for the reason as follows –

All business, all consumers, all people need certain basics to survive – Food – Water -Shelter and Land upon which to do all the above.

——So with all the lending – as much as possible then and today with PE and leverage; risk be damned as they knew bailouts would be used in that great con and it’s new version of the old today- — Its only outcome was to raise the cost of housing – rent (land), business overhead, farm land prices thus products therefrom and everything produced on the planet (people playing the real estate game and realtors and all associated, wrongly believed they were gaining wealth but – it was zero gain because if you wanted to continue living you had to pay the higher costs wrought by the great con game – this con perpetrated by financial puffers and criminals – aided by many of the rest of us who were conned into thinking this great inflation of assets was and is the only way – the brave, heroic, patriotic – survival of the fittest, smartest, hard earned way to get ahead – and be damned those who didn’t jump on board the great gravy train robbery –

Of course, as this is all now the norm, and all made proper by great grants made to the institutions of higher learning (to make sure the proper economic and finance learning is taught) and larger grants made to the institutions of government (to make sure the proper economic and financial governing is practiced) so the rest of can be assured that the criminals the corruption and fraud is protected by law and the aristocracy is free to do as they wish – as of course is their inherited right.

So the planet burns and a virus is showing us how the (current false definition) Free Market has – and continues to screw the vast majority of the planet out of the planet.

I hope that more people really start to examine and propose alternatives to the current FIRE sector Free Market which is and continues to be the true and only impediment to solving the worlds problems IE sixth extinction event and global geochemical disaster (global warming is one).

I propose taxing the crap out of rentier activities and financial predation – Tax the crap out of those things known to cause asset price inflation and are destructive to the planet and raise the cost of living.

The Free Market needs to mean Free From Rentier, Preditory, and Unnecessary overhead tolls.

Currently the negative is taxed lightly and the positive is burdened –

Switch the burdens around and the easy money would be made by doing the right thing – it would make earning money through financial predation much more difficult.

Anyway – some random thought to chew on –

And yes – should investors ever take losses on money lent on interest? – sure they should – why I thought that is why interest was charged – shows ya how little I know.

And if investors take losses based on False Warranties and Representations made by the financial engineers – well let them engineers make it up to the investors – instead of what happened in 2008 when Obama (I voted for him which makes me a sucker) saved em from pitchforks.

Thank you for your well articulated comments! You expressed my thoughts better than I could ever have done.

Any betting on whether the CLO holders or the public comes out on top in this game?

Hi all, this one is right in my wheelhouse as I spent 10+ years working for one of the big CLO Trustees.

Yves’ take is generally correct. What I find most comforting is that there was never a return of structures that incorporated a ton of CDS contracts. In fact, I haven’t seen any kind of return of CDS contracts at all. Good riddance! Those things were poison!

Lehman did a ton of those pre-crisis and when they went bust, they left a big legal and financial mess as the deals couldn’t function without Lehman in the middle of them. They had way too many conflicting roles. I suspect a lot of them were created for Lehman to lay off risk onto their wealth management customers and other marks.

CDSese trade, especially the indices and names that are in the indices, but those generally tend to have a fairly liquid underlying bond market. And the overall CDS market is fraction of what it used to be.

Fortunately though the more idiotic CDSes (like the LCDS – CDS on leveraged loans) are gone, and as you say, the synthetic CLOs too..

Thank you for these details. A little surprising. And as if I didn’t already hate PE enough. One of the surprising things is that the Fed did actually show some restraint. I hope it holds. I think we need to emancipate PE from the Market altogether.

wow Yves! great takedown in the Swiftian style (hilaris in triste) of savage indignation.

Some economists have studied what happened to those $1,200 stimulus checks. People who made less than $1,000/month spent them quickly while people making over $5,000/month mainly saved the stimulus money. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/this-is-how-fast-americans-are-spending-their-stimulus-checks-and-heres-a-breakdown-of-what-theyre-buying-2020-05-15?mod=home-page

The obvious conclusion from this study is that future stimulus money should be focused on the wealthy so they can keep their asset base intact.

Great post and comments. Thanks.

How did we get here?

Economics, the time line:

Classical economics – observations and deductions from the world of small state, unregulated capitalism around them

Neoclassical economics – Where did that come from?

Keynesian economics – observations, deductions and fixes for the problems of neoclassical economics

Neoclassical economics – Why is that back again?

We thought small state, unregulated capitalism was something that it wasn’t as our ideas came from neoclassical economics, which has little connection with classical economics.

On bringing it back again, we had lost everything that had been learned in the 1930s, by which time it had already demonstrated its flaws.

The Mont Pelerin society developed the parallel universe of neoliberalism from neoclassical economics.

FDR saved capitalism from itself with the New Deal.

Many right wingers weren’t happy about this at all and longed for the good old days when they had the economic freedom to make lots of money and bring capitalism to its knees.

Of course, they didn’t take any responsibility for the problems they had caused and they plotted to get back to the way things had been before.

In the 1980s they succeeded, but all the old problems would re-emerge.

1929 and 2008 look so similar because they are, it’s the same economics and thinking.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAStZJCKmbU&list=PLmtuEaMvhDZZQLxg24CAiFgZYldtoCR-R&index=6

At 18 mins.

As a CEO, I can use the company’s money to do share buybacks, boost the share price, cash in my share options and get my bonus.

Share buybacks were found to be a cause of the 1929 crash and made illegal in the 1930s.

What lifted US stocks to 1929 levels in 1929?

Margin lending and share buybacks.

What lifted US stocks to 1929 levels in 2019?

Margin lending and share buybacks.

A former US congressman has been looking at the data.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7zu3SgXx3q4

At the end of the 1920s, the US was a ponzi scheme of over-inflated asset prices.

The use of neoclassical economics and the belief in free markets, made them think that over-inflated asset prices represented real wealth accumulation.

1929 – Wakey, wakey time

Let’s have another go.

Oh blimey, it’s still the same.

Why did it cause the US financial system to collapse?

Bankers get to create money out of nothing, through bank loans, and get to charge interest on it.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

What could possibly go wrong?

Bankers do need to ensure the vast majority of that money gets paid back, and this is where they keep falling flat on their faces.

Banking requires prudent lending.

If someone can’t repay a loan, they need to repossess that asset and sell it to recoup that money. If they use bank loans to inflate asset prices they get into a world of trouble when those asset prices collapse.

As the real estate and stock market collapsed the banks became insolvent as their assets didn’t cover their liabilities.

They could no longer repossess and sell those assets to cover the outstanding loans and they do need to get most of the money they lend out back again to balance their books.

The banks become insolvent and collapsed, along with the US economy.

When banks have been lending to inflate asset prices the financial system is in a precarious state and can easily collapse.

“It’s nearly $14 trillion pyramid of super leveraged toxic assets was built on the back of $1.4 trillion of US sub-prime loans, and dispersed throughout the world” All the Presidents Bankers, Nomi Prins.

When this little lot lost almost all its value overnight, the Western banking system became insolvent.

Western taxpayers had to recapitalise the banks and make up for all the loses the bankers had made on bad loans they had made to inflate asset prices.

Free market thinking split into two separate paths in the 1930s.

We took the wrong path.

In the 1930s, Hayek was as the London School of Economics trying to put a new slant on old ideas, while the Americans were working out what had gone wrong in the 1920s.

The University of Chicago had worked out what had gone wrong with free market thinking before, but we followed Hayek who hadn’t.

In the 1930s, the University of Chicago realised it was the bank’s ability to create money that had upset their free market theories.

The Chicago Plan was named after its strongest proponent, Henry Simons, from the University of Chicago.

He wanted free markets in every other area, but Government created money.

To get meaningful price signals from the markets they had to take away the bank’s ability to create money.

Henry Simons was a founder member of the Chicago School of Economics and he had worked out what was wrong with his beliefs in free markets in the 1930s.

Banks can inflate asset prices with the money they create from bank loans.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

Henry Simons and Irving Fisher supported the Chicago Plan to take away the bankers ability to create money.

“Simons envisioned banks that would have a choice of two types of holdings: long-term bonds and cash. Simultaneously, they would hold increased reserves, up to 100%. Simons saw this as beneficial in that its ultimate consequences would be the prevention of “bank-financed inflation of securities and real estate” through the leveraged creation of secondary forms of money.”

https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Henry_Calvert_Simons

Real estate lending was actually the biggest problem lending category leading to 1929.

Richard Vague had noticed real estate lending balloon from 5 trillion to 10 trillion from 2001 – 2007 and went back to look at the data before 1929.

Henry Simons and Irving Fisher supported the Chicago Plan to take away the bankers ability to create money.

“Stocks have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” Irving Fisher 1929.

This 1920’s neoclassical economist that believed in free markets knew this was a stable equilibrium. He became a laughing stock, but worked out where he had gone wrong.

Banks can inflate asset prices with the money they create from bank loans, and he knew his belief in free markets was dependent on the Chicago Plan, as he had worked out the cause of his earlier mistake.

Margin lending had inflated the US stock market to ridiculous levels.

The IMF re-visited the Chicago plan after 2008.

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp12202.pdf

“……. they plotted to get back to the way things had been before.”

I’ve got a good idea, you’ll like this.

You can attract modern liberals to dodgy, old, 1920’s neoclassical economics if you bolt on identity politics.

Inequality exists on two axes:

Y-axis – top to bottom

X-axis – Across genders, races, etc …..

The traditional Left work on the Y-axis and would be a problem as you want to increase Y-axis inequality.

The Liberal Left will work on the X-axis.

You can increase Y-axis inequality while the Liberal left are busy on the X-axis.

The 1930’s solution of the Chicago Plan was one way of keeping bank credit out of the markets.

There are other ways.

You could use the corset controls the UK used before 1980.

This kept bank credit away from financial speculation and debt grew with GDP.

https://www.housepricecrash.co.uk/forum/uploads/monthly_2018_02/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13_53_09.png.e32e8fee4ffd68b566ed5235dc1266c2.png

Before 1980 – banks lending into the right places that result in GDP growth (business and industry, creating new products and services in the economy)

Debt grows with GDP

After 1980 – banks lending into the wrong places that don’t result in GDP growth (real estate and financial speculation)

Debt rises faster than GDP

OR …..

Richard Werner worked out what went wrong in Japan.

The BoJ used to use window/credit guidance to steer bank credit away from financial speculation and towards business and industry.

This was the basis for all the Asian Tiger economies, until they discovered financial liberalisation and the Asian Crisis followed shortly after that.

OR …..

Germany uses small non-profit banks that are very local to communities and businesses.

There is no gain from financial speculation and they are closely tied to the people they serve.

Awesome piece, Yves! Remember your outstanding work from 10 years go) Couple of questions:

1. Dont you think the derivatives will be a problem again? This time due to corporate credit risk and FX moves? CDS exposure to GM, GE, Ford is many times their cash debt and should they go down (even if the Fed holds bonds) the CDS losses could be in many trillions if we account for all possible corporate defaults. Also, FX derivatives notional is orders of magnitude larger than credit one and large swings in euro/dollar etc could also kill a lot of players.

2. Isn’t PE in trouble? Some of them are clearly OK but is it really true that all of PE players are sitting on mountains of cash? I am far from this market, could anybody opine on which PE firms could be hurt?)) TIA!))

I didn’t speak of derivatives generally but of CDS, which aren’t even proper derivatives but are unregulated insurance agreements.

CDS are now unlikely to pay out. Per John Dizard of the Financial Times:

https://www.ft.com/content/a6cd6130-542f-11e8-b24e-cad6aa67e23e

FX trading volumes have pretty much always been larger than credit volumes, and there is greater commercial need to hedge FX than credit, so I’m not surprised that FX notional is higher. So that alone isn’t a basis for concern.

Re PE, PE firms will not go bust. They are asset managers and 2/3 of their fees are not related to performance.