As more and more private equity-owned companies are failing, the great unwashed public is starting to take notice and wonder why. Even before the coronacrisis arrived, the mainstream media was documenting the outsized role of private equity in the bankruptcies of retailers, restaurants, and even stores like Fairway. Sometimes, as with Toys’R’Us, it was too much leverage exacting a toll. In others, it was asset-stripping that increased operating leverage, specifically selling company-owned real estate at inflated priced because it was being leased back at high rent rates.

The Wall Street Journal sets forth some of the reasons why private equity fund managers like Apollo, Blackstone, and KKR don’t ride in to the rescue when companies they have acquired go wobbly.

Not only are the points the Journal makes not entirely accurate, they also manage to skip over the most relevant reasons. And in doing so, they whitewash private equity conduct.

The Journal tries to explain the conundrum of the private equity industry collectively having access to $1.45 trillion of “dry powder,” meaning yet-to-be-deployed investor committed capital, yet standing pat as companies in their funds fail due to coronacrisis revenue hits:

Thirty-four U.S. private-equity-backed companies filed for bankruptcy from March 1 through June 14, according to data provider PitchBook Inc., including well-known names such as Hertz Global Holdings Inc., Neiman Marcus Group Inc. and J.Crew Group Inc.

The private-equity owners of some bankrupt companies had no shortage of cash to spend. Ares Management Corp., which bought Neiman Marcus in 2013 alongside the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, was sitting on more than $33 billion of dry powder shortly before the luxury retailer filed for bankruptcy last month. Ares declined to comment, and the CPPIB didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The big justification for this disconnect is the “going bust” companies are in older funds, while money waiting to be spent is in newer funds, and they allegedly can’t use the new fund money on older deals:

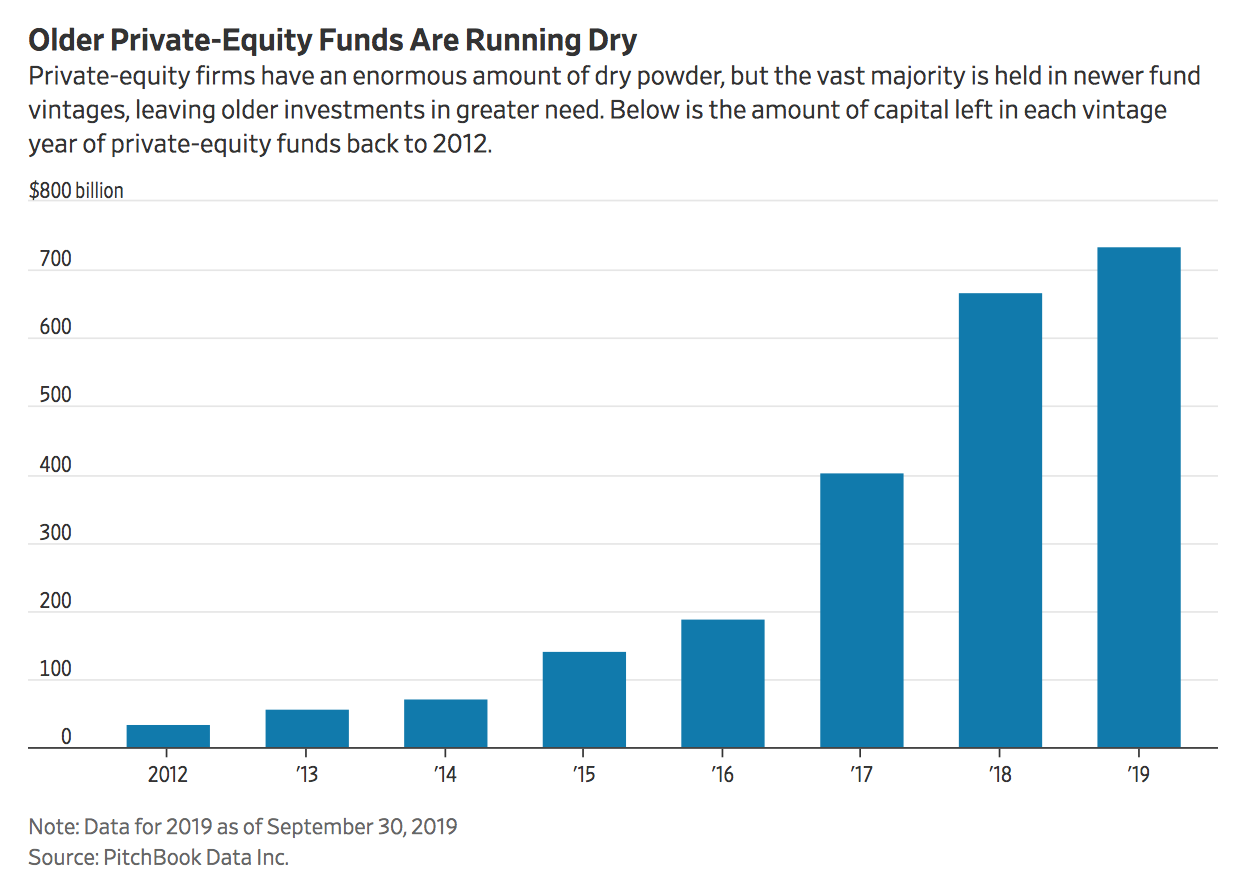

Of all the dry powder in the buyout industry, about 85% is earmarked for funds raised from 2017 to 2019, according to analysis by the investment and consulting firm Cambridge Associates.

Funds raised in earlier years are “running on fumes,” said Andrea Auerbach, head of global private investments for Cambridge.

Older funds “sailed right into the Covid crisis without additional capital available to support their companies as easily as the more recent vintage years,” she said.

This excuse is bogus. Private equity limited partnership agreements often contemplate that the fund manager (the general partner) may be allocating an investment in a particular portfolio company among several funds, which needless to say would seem to represent a conflict of interest. The limited partnership agreement provides for the general partner considering interests other than those of the limited partners in its fund in making those decisions….including its own interest!

Without mentioning these contractual provisions, the Journal confirms that managers of multiple funds can and do have newer funds invest in the companies of older funds:

Transactions in which a firm invests in a company it already owns, but from a newer fund—so-called cross-fund investments—were on the rise before the coronavirus struck, and allow private equity to use newly raised money to support older investments. But industry observers have seen little use of this strategy to support struggling companies during the pandemic.

Another spurious private equity defense:

Investor sentiment creates another barrier to using dry powder to keep struggling businesses afloat. Investors in private-equity funds, referred to as limited partners, are rarely enthusiastic about new money being spent to rehabilitate struggling businesses, preferring that managers buy new ones that can be had at cut rates amid a slowing global economy.

“Investor sentiment”? This is laughable. What about “limited partner” don’t you understand? Limited partners have zero say in general partner decision-making. Moreover, they have a well-established history of acting like battered spouses who won’t leave their abuser. We have been chronicling for six years how private equity limited partners are unhappy about the way general partners refuse to disclose how much money they are sucking out of the companies they control. Yet they continue to accept what out to be unacceptable terms, despite the fact that private equity since at least 2006 has not outperformed public equity. There’s no good reason for this misguided loyalty (and we’ve described the many bad reasons, soft and hard corruption being high on the list).

More specifically, private equity funds have the fig leaf of advisory committees, which the general partner stacks with guaranteed not-to-rock-the-boat limited partners like fund of funds that will never vote against the general partner. The Wall Street Journal completely misleads readers with this section:

In a recent poll of limited partners conducted by ILPA, just 10% chose cross-fund investments as the preferred way to preserve value in older companies, among a slate of options Ms. Choi said.

More popular among limited partners, she said, was a practice called recycling, in which the earnings from a successful investment are used to support other companies in the same fund, instead of being immediately returned to investors.

Like cross-fund investments, recycling requires approval from investors, and can sometimes ruffle the feathers of limited partners with their own liquidity issues.

The only “approvals” are by the captured advisory committees. And since the general partners make sure they have comfortably more than 50% of the votes, it isn’t hard to imagine that this supposed limited partner disapproval significantly reflects their antipathy for using newer money to help out older funds.

On top of that, the article also misses a key point regarding “recycling”: that general partners often syphon out excessive funds via paying carry fees on a deal by deal basis. As we’ll discuss more below, general partners realize profits on their better deals early on. And unlike “European” agreements, they can pull out carry fees on a deal-by-deal basis once they’ve met a hurdle rate. However, the profits on early deals can be offset by losses on later ones. The limited partnership agreements provide for “clawbacks” of these overpaid carry fees, but industry insiders report that the general partners never pay the monies back. Instead, they offer a deal on their next fund. Any excessive carry fees should also be available to shore up floundering companies….but private equity general partners reportedly don’t volunteer that they’ve taken more than they should have.

So why don’t general partners try to salvage investee companies that get sick? They have no reason to.

First, as private equity mavens Eileen Appelbaum and Rosemary Batt ascertained, over 60% of the fees general partners receive have nothing to do with the performance of the investment. They get rich whether companies do well or fail.

Second, the general partners don’t care much about fund performance after year 4 or 5 of a fund. The reason is that they have typically raised money for a new fund by then. In other words, what matters (mainly) in fundraising is the early-years performance of the most recent offering. So general partners are highly motivated to realize profits on winners early. And the pervasive use of internal rate of return to measure those results further exaggerates the impact of early realized profits. An extreme case: one fund showed a 77% return when it came time for it to raise a new fund. The final returns on that fund? 11%.

Thus the deals in a fund in its later years almost by definition are mediocre to dogs. And since their crappy performance will come in too late to make a difference in fundraising, the general partner has little motivation to try to salvage them.

We get the final excuse on behalf of private equity, from an industry lobbyist, which is an insult to intelligence:

Even if firms wanted to use newly raised money to prevent an older investment from falling into bankruptcy, they might be limited by fiduciary obligations to investors that committed that money to them, said Brett Palmer, president of the Small Business Investor Alliance.

Oh come on. Fiduciary duty? When private equity firms charge fees without rendering any services, the so-called monitoring fees that Oxford Professor Ludovic Phalippou has called “money for nothing“? Or widespread abuses of private jets? Just check the tail numbers of planes owned by private equity firms and charged to their limited partners and see where they go on Super Bowl Sunday, Valentine’s Day, and around major holidays.1

If the private firms were so big on fiduciary duty, why would they go to such lengths to waive it in their agreements? Provisions that allow general partners to consider interests other than those of their investors are a waiver of fiduciary duty. So are the sweeping indemnification provisions that are pervasive in limited partnership agreements.

In fact, some states like Kentucky have extremely tough, binding fiduciary duty provisions. But as the rampant crooked conduct and abject performance of the Kentucky Retirement System (only 13% funded) shows, the fund managers seemed awfully confident that they’d never be held to account. A lawsuit against KKR/Prisma, Blackstone, and PAAMCO will test that belief.

A final issue is that private equity general partners are not turnaround artists. So their temperament and training would incline them to move on to the next kill rather than try to play Mr. Fixit.

Now admittedly, some companies can’t be saved from bankruptcy and others can be kept out of court only with some painful bloodletting. But you don’t see arguments like that in this piece. Instead, it attempts to justify not trying at all. Wth private equity, the best explanation ever and always is “Follow the money” as in the general partner’s money.

_______

1 The firms piously claim that employees pay for non-business trips. If you believe that, I have a bridge I’d like to sell you.

Learn from the private equity experts:

Cash-out refi of mortgage.

Max-out HELOC.

Set up various shell legal entities.

Pay yourself a bonus, quickly convert to Au and Ag.

“Asset-strip, like Mitt!”

r.i.p Chainsaw Al.

http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2025898_2025900_2026107,00.html

Isn’t it pretty much the point of (some forms of) private equity, that it puts acquired firms at a real risk of bankruptcy? They have to extract money from a firm that previous owners did not already suck out. A greater willingness to risk bankruptcy is one way to do that.

It’s, among other things, a negotiation tactic. They suck most reserves out of the firm, and then they let management renegotiate contracts with the back against the wall. Workers, customers, suppliers, everyone is asked to “chip in” to help save the firm because the alternative is worse for everyone.

That tactic only works if the PE owners are genuinely willing to let firms go bust, and if they do not easily put in new capital. In some individual cases, it might be beneficial to the PE guys to raise new capital and avoid bankruptcy, but in the longer run those bankruptcies give them credence in future negotiations. Give up your pensions, accept the wage cuts, endless payment delays for supplies, etc. And if you don’t accept, the firm goes bust pour encourager les autres, as they say.

For a long time now I have thought of private-equity corporations as the “Chop-shop” firms of the business world but this Wall Street Journal defense of them does seem a bit off. Don’t they have more important stories to cover? Which makes me wonder. After the past six months a lot of corporations and the like are now realizing that the pandemic is going nowhere anytime soon and business as we know it may have to be reconfigured into a different shape. The tide has gone out and it may be that some of those with the biggest dangly bits are private-equity corporations. If actual profit once more comes into vogue, it may be that some senior people have decided that the numbers associated with these firms do not look good and are going to revisit some contracts which has led to this defense by the Wall Street Journal of them here. Just a theory mind.

It sounded that way to me too. Makes me wonder just what the shelf-life is for PE funds themselves. How do they keep rolling when the market does not come back? I’d think no clever bookkeeping can hide what they are doing. And even the most desperate pension funds will stop buying into them. So how will PE cut their artful losses then?

Paired with the story about banks no longer knowing how to assess the current credit risks to business, I wonder if PE will find getting loans or floating junk bonds harder to do. Since the name of the PE game seems to be credit and debt arbitrage, a reduction in credit could spell big trouble for PE. Oh, wait… there’s still the ‘dumb money’ like CalPERS willing to invest. ;)

Private equity does the most good for the general partners. The limited partners get the leavings. Is there any social utility or is it simply about the profit of a few?

It appears we have also reinvented Medieval style Barons – General Partners, accountable to nobody.

It would be instructive for WSJ and other media readers to see summaries of their stories, rather than burying the lede or just hiding it.

XYZ Company paid x,

extracted y,

occurring over z time period,

resulting in @#$% returns to each investor class and

$$$$ fees extracted.

That same approach would be helpful at CalPERs and others, so there is some semblance of transmission of knowledge instead of obfuscation. Feature, not bug.

Coursework at HBS, Booth and similar MBA factories may also provide some tuition regarding current methods and practices. Just how are the next generation of leaders being groomed to extract maximum coinage while limiting what used to be known quaintly downside risk? Silly to ask but are there still ethics classes?

Now that downside risk includes people, so just paper over and immunize against that.

What would our economy look kike without all this pork? I suspect the numbers would be damming for an administration.

For example, the accurately named Gerald Ford class of aircraft carriers is a disaster for who?

Armies win, or loose, wars and occupy territory.

Mayberry looks like it could be a clear case of fraud, complete with intent. The judge is quoted as ruling that the case couldn’t be restricted by any statute of limitations because the limited partners (pension fund) didn’t have the necessary information to bring an action. I don’t know why PE hasn’t been sued out of existence already for fraud… all PE has done is keep corporations struggling to stay alive while they dine on them.

One question I’ve always had with PE is what is the legal doctrine/structure that allows the buyer of an asset to not just use that asset as collateral in order to borrow the takeover funds, but actually make the asset itself a borrower. How does that work?

I would love to purchase a house, but have the house be the title to the mortgage.

Hmmmm…… I’ve never thought of PE as an advanced form of check kiting, but you may have something there. ;)

I strongly recommend spending 30 minutes listening to this lecture by Ludovic Phalippou of the Said Business School at Oxford University to acquire a good understanding of private equity.

My apologies. The link didn’t seem to come through. I will enter it again here. It can also be found on page 355 in note 22 of the book Makers and Takers by Rana Foroohar (2016) Crown.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m1paFqPIj6Q

For some reason, I am unable to include a link in my previous comment.I recommend looking at note 22 on page 355 of the book Makers and Takers by Rana Foroohar (2016) Crown for the link.

The June 15 post by Yves on private equity should be read in conjunction with this post. Prof Phalippou, mentioned there, has been researching the topic of private equity diligently. He is a marvelous lecturer though one must listen closely as he has a slight accent.

He also has a wry sense of humour. The youtube lecture captures this perfectly and will introduce you to private equity in a way that simple text cannot.

The key to private equity “success” is their ability to borrow loads of money to acquire a company, AND then have zero responsibility for paying down the loans. The debt is held on the books of the acquired company. In the meantime, private equity will extract “special dividends” and “management fees” from the acquired company. If said company fails private equity has previously won since they skimmed the wealth off the top and left the liabilities to the investors. Elizabeth Warren said she would introduce legislation that would require private equity to be liable for the debt they use to acquire companies. It is not likely she will succeed due to the lobby power of private equity.

The recent SCOTUS decision on Thole v. U.S. Bank… that opens the doors wide for corporate America to steal with impunity from the pension plans: https://www.unz.com/estriker/corrupt-supreme-court-gives-green-light-to-corporations-to-steal-from-pensioners/

What I’ve never understood is why creditors of PE-owned companies are so passively willing to give the General Partners a free pass. The corporate veil between portfolio companies and their PE masters is more often than not transparently fraudulent and designed to screw creditors in bankruptcy.

It seems to me that courts ought to be more willing to “pierce the corporate veil” of these sham corporate ownership structures and to allow creditors to claw back equity from the owners who controlled and stripped the portfolio companies to the detriment of their suppliers.

Many (perhaps most?) of these creditors are in on the game. They do repeat business with PE firms. They have a reasonable grasp on what is going to happen, and on what risks they are taking. They adjust their terms accordingly – higher interest, limited loan-to-value ratios, and their own sometimes sophisticated valuation of the value.

If the underlying companies survives the bloodletting for long enough, then the higher interest gives them a share in proceeds. If the company does go under, the lenders are now the new owners (for a low price, since they had lend out less money then their own estimate of the value).

In the latter case, you see a repeated bloodletting, where the new owners do a new and harder round of squeezing. Some lenders specialize in that themselves, sometimes they sell on to other who specialize in second-squeezing firms that went bust due to PE practices.

Something similar happens in the ‘good’ outcome when the company survives long enough. The PE firms sells on the remainder, often to people who knowingly specialize in buying the leftovers of PE bloodletting.

It’s a whole ecosystem. Obviously, they do try to trick each other, they are finance people after all. But the insiders have reputations to guard, so the tricks have to be “fair” or they lose future business.

I guess the hard part is knowing when you are a real insider, and when you are the mark at the poker table who only thinks he’s an insider. My reading of Yves’ Calpers articles is that pension funds are often such marks. Made to believe that they are sharks sharing in the feast, while in reality they are themselves also on the table.