By Lambert Strether of Corrente

I’m afraid this is a post where I did indeed catch a bird, just not the one that I intended to catch. I had thought to write a post the Mekong River part of the biosphere (as with coral, mangroves, soil, and algae in Lake Erie) but as it turned out, all the recent news on the topic was polluted by a State Department propaganda operation (pause here to give the Administration and Secretary Pompeo credit for more subtlety than they usually display). So instead of going into any detail on the Mekong — from the poetic Thai and Lao mae khong, or “Mother of Waters” (river) “Khong,” and don’t @ me, Southeast Asian language mavens — I’ll pause to appreciate its beauty, give a brief description of it as ecological system, present the geopolitical situation, and then dive into the swirl of opinion generated by the State Department’s report. I’ll conclude with a brief description of how (some) NGOs conceive of the problem. (That means I won’t get to quote from this excellent article in the Financial Times on sand mining in the Mekong delta: “The Mekong Delta: an unsettling portrait of coastal collapse,” which you should go read if you’re interested in that part of the world[1].)

But first, the beauty part:

Absurdly touristic but still beatiful:

A floating village:

(This image reminds me of LeGuin’s Raft People in The Farthest Shore; I don’t want to romanticize the villages, but I feel, and I feel that the elders would feel, that something would be lost if they disappeared, even if there’s no satellite dish in sight.)

Turning to the Mekong as an ecological system, from “Mekong Wonders” at ArcGis (well worth a read itself).

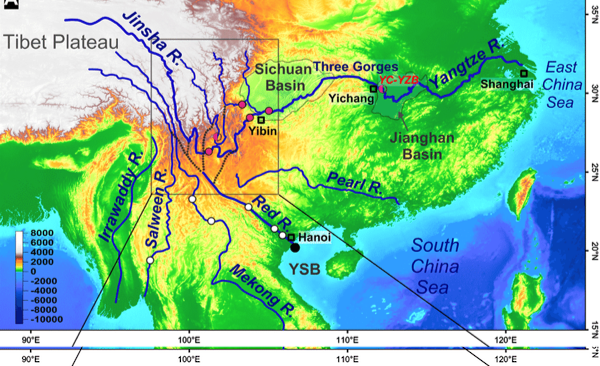

The Mekong River rises in the glaciated Tibetan Plateau and flows through six countries (China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam) in South East Asia, and is the 12th longest river (4909 km) in the world and the 3rd longest in Asia. In terms of average discharge the Mekong is 18th largest river in the world at 16,000 m3/s putting it just behind the Mississippi River. However, the Mekong River swells annually during the monsoon season to approximately 39,000 m3/s. The Mekong Basin is roughly the size of the country of Chile, hosts over 398 languages, contains important cultural and archaeological sites, and is among the most biodiverse regions of the world.

The Mekong River Commission amplifies in “The Flow of the Mekong” (PDF):

By any set of measures, such as length, mean annual flow, the diversity of its plant and animal life or the size and diversity of the aquatic resources, the Mekong is one of the world’s great river systems. The livelihoods of 40 million of the basin’s inhabitants in some way involve fishing, and the tremendous power of its tributaries provides the economies of countries that share the basin income through the development of large-scale hydropower projects.

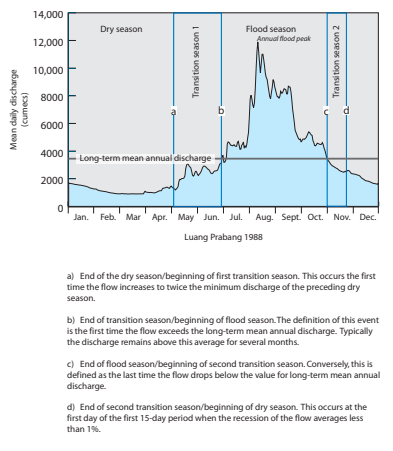

Again, the Mekong’s key feature (“swells annually”) is the “flood pulse”:

Many of these water resources stem from the river’s regular ‘flood-pulse’ hydrological regime. This means that the seasonal pattern of flood and recession are predictable even though their magnitude and extent can vary significantly from year to year. The rich animal and plant life that comprise the river’s diverse ecosystems have evolved in tune with the seasonal hydrological cycle, as have the societies and cultures of the people who live beside it.

The MRC provides a chart of the flood pulse; as you can see, it’s pretty big:

Mekong Wonders provides an aerial view of the flood pulse over several years:

The flood pulse causes the extraordinary and unique reversal of flow in Tonle Sap, the enormous lake where the floating village (above) was located. Mekong Wonders once more:

The flood pulse is the beating heart of the lower Mekong River and its tributaries. The flood pulse is a seasonal pattern that occurs in response to monsoonal rains. Every year during the rainy season (June through October) the rivers, wetlands, and fields swell so much that the flow of the Tonle Sap River reverses and increases the size of the Tonle Sap Lake by 6 times its dry season size. Even at its dry season size (2,700 km2), the Tonle Sap Lake is the largest inland lake in Southeast Asia. The immense aquatic productivity that results from this globally-unique flood pulse is due to the diversity of land cover types and the presence of a unique freshwater mangrove belt known as the flooded forest that surrounds the Tonle Sap Lake. The annual cycle of flooding with its influxes of sediment and nutrients, combined with the habitat of the flooded forest, provides optimal conditions for the rearing of young fish. The flood pulse sustains the ecosystem and drives this enormously productive and diverse fishery that feeds 60 million people.

This is such a wondrous system that I probably spent too much time on it! With that, let us turn to geopolitics. You will have noted that this wondrous system is dependent on the Mekong’s seasonal flow. Today, that flow has two charactertics. First, China controls the Mekong’s headwaters, which originate, together with the Irrawaddy and the Saleween, in the Tibetan plateau[2] controlled by China:

Second, the Mekong is increasingly dammed, both within China, or further downstead in Cambodia and Laos, countries aligned with China. From the Stimson Center, to which we will return:

(This map gives only the main dams; the Mekong Dams Observatory tracks 805 dams in the region, of which 212 are “commissioned power dams.”)

The resulting power relation — that China can turn off the taps — is well expressed in the following two cartoons from the region:

And more subtly:

Now, dams as such interfere with the Mekong’s flow, especially the flood pulse. From National Geographic, “Harnessing the Mekong or Killing It?,” 2015:

Boontom is the leader of Ban Pak Ing, a scattering of cinder block houses and unpaved streets that reach from the precipitous west bank of the Mekong toward a quiet, well-cared-for Buddhist temple. Twenty years ago, like many of his neighbors, Boontom caught fish for a living. But as China completed one, then two, and then seven dams upstream, the few hundred residents of Ban Pak Ing saw the Mekong change. The sudden fluctuations in water levels interfere with fish migration and spawning. Though the village has protected local spawning grounds, there are no longer enough fish to go around….

Until 2012 another village lay immediately downstream of the dam site. In 2013 its residents were settling into a grid of new cinder-block-and-wood houses well out of the river canyon. There, optimism was scarce. Residents said the money and land promised by the dam company as compensation for relocating were inadequate and slow in coming. Many were feeling the unfamiliar bite of the cash economy. “In the old village you didn’t make much money, but you could eat the rice you grew,” said a young woman with two children. “Here you can make money every day, but every day you have to spend more than you make.”

(That’s not a bug. It’s a feature.) However, the accusation made by the cartoons is more specific: It is that China used its dams deliberately to choke off the water supply to those downstream. And here we enter the realm of State Department Propaganda (and it certainly would have been easier if I had run across this link first. From the Center for Strategic and International Studies:

The image promoted by Minister Wang was one of a benevolent China willing to help its neighbors during a time of hardship. A new study funded by the U.S. State Department paints a less rosy picture—one in which Chinese dams, and not mother nature, were the main culprit behind dwindling water levels. The report found that the Mekong’s upper basin in China actually received above-average precipitation in 2019. Had the Mekong’s flow not been obstructed by Chinese dams, areas along the Thai-Lao border would have experienced slightly higher-than-usual water levels.

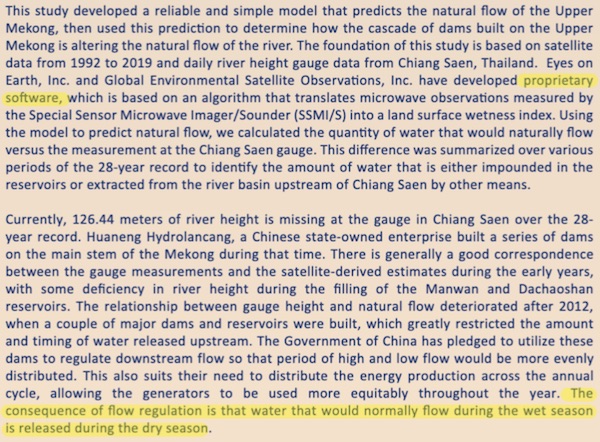

A study “funded by the U.S. State Department”, eh? It’s from Eyes on Earth, “Monitoring the Quantity of Water Flowing Through the Upper Mekong Basin Under Natural (Unimpeded Conditions), and published on April 10, 2020. Here is material from the Executive Summary (for which the PDF, whether out of cyncism or indifference, is images only, so text cannot be copied or searched). First excerpt (proprietary software, eh?):

Exactly as Boontom noticed, in 2015.

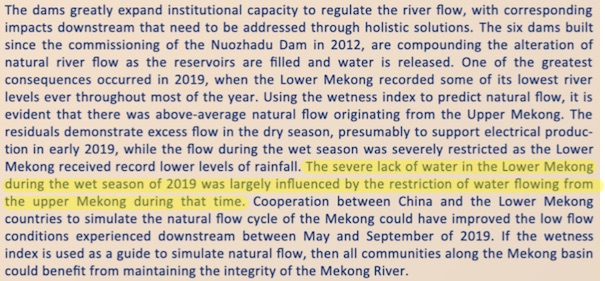

Second excerpt, which is the one that says, in very academic language, that China did indeed turn off the taps:

The study subseqently got play at the Stimson Center, Foreign Policy[3], The Diplomat, Al Jazeera, and the New York Times, to name a few. And the study’s conclusion is certainly plausible; all you have to do is look at a map and think about power relations. But is the study true?

At best, that remains to be seen. From Tarek Ketelsen, Timo Räsänen, and John Sawdon[4], “Did China turn off the Lower Mekong? Why data matters for cooperation“:

The Eyes on Earth study uses satellite data to provide information on flow in the Lancang River, China’s name for their stretch of the Mekong. The analysis uses microwave imager data to develop a “wetness index”, which estimates the amount of water in the river catchment. Statistical analysis is then used to establish a relationship between the “wetness” of the catchment and monthly water levels at Chiang Saen station.

Concerns regarding the study have been expressed including by the Mekong River Commission Secretariat (MRCS), academics, as well by us at AMPERES.

First, a simple regression model may not adequately capture the complex hydrological processes (e.g. groundwater dynamics) of the Lancang River. Second, the use of water level data alone does not give understanding of the water volumes flowing in the river or water volumes stored and released by the reservoirs.

Third, the study also discusses water level and flow volumes interchangeably, which they should not be. Fourth, monthly water level data is too coarse to reflect hydropower operations occurring over much shorter time scales. Fifth, water flows in the Mekong are highly variable, and the baseline used in the study is too short to allow the reliable identification of a relationship between water levels in the river and wetness in the upstream catchment.

Finally, the study makes almost no reference to peer-reviewed literature on the Mekong system from the past 15-20 years, nor any evidence of the study having undergone a peer-review process – two critical safeguards in the scientific process.

(Everybody seems to want cooperation in the Mekong, but nobody seems to have any idea how to achieve it.)

However:

Despite these concerns, the main technical findings of the Eyes on Earth study are however consistent with the prevailing scientific understanding.

The answer lies in how the study has been used as evidence for a simplified narrative that blames China for the drought. With the Eyes on Earth study in hand, the Stimson Center claims that drought in the Lower Mekong was the direct result of Chinese water management policy, that China is hoarding water.

The Stimson Center concluded that although the Lancang catchment received an above average amount of rain and snowmelt, nearly all the water remained trapped behind China’s dams. This contradicts earlier research, indeed our calculations suggest that the whole cascade of 11 dams could only store around 35-37% of wet season flow in an average year, even less during a year with above average water availability.

The political conclusions drawn and widely disseminated by the Stimson Center are not substantiated by the Eyes on Earth study. These claims represent a politicisation of data. One that risks undermining the integrity of efforts by a community of researchers to build, over decades, a credible evidence base on the functioning of the Mekong system.

And that is where the controversy stands, so I will leave it behind for now. However, the geography is what it is; and the power relations are what they are, so one would expect this issue to crop up once again.

Conclusion

The water wars in Southeast Asia show no prospect of getting any easier, and are unlikely to, as long as water is conceived of as the World Wildlife Foundation concieves of it:

“Water is liquid capital and it flows through the economy just as much as it does through our rivers and lakes,” says Stuart Orr, Leader of the WWF Water Practice. “Water underpins our agricultural systems, our energy production, manufacturing, ecosystems, food security and our wellbeing as humans.”

And the Eyes on Earth study itself, quoted in the Japan Times:

The authors of the Eye on Earth study argue that “the Chinese are building safe deposit boxes on the upper Mekong because they know the bank account is going to be depleted eventually and they want to keep it in reserve.”

I wish the National Geographic reporter had given the name of the young lady in Boontom’s village (“you could eat the rice you grew”); I doubt very much whether she would share the WWF’s opinion, or Eyes of Earth’s. Nation-states have not been notably successful at sharing capital, have they? So I fear for the region, besides the beauty of the river.

NOTES

[1] Here from the cutting room floor is an article on the restoration of mangrove forests in the Mekong Delta.

[2] Hence dependent on Tibetan glaciers, which was to be one climate change aspect of the post as originally conceived.

[3] Headline: “Science Shows Chinese Dams Are Devastating the Mekong.” If I hear “science” one more time on any politicized matter, I’m gonna start getting cynical. I’m for science. But science, as any scientist will tell you, must be tested, and not used as an argument from authority.

[4] All from AMPERES (Australia Mekong Partnership for Environmental Resources and Energy Systems), so far as I can tell not funded by China, although they have business interests in the Mekong area. More information from China hands in the commentariat welcome.

Who doesn’t love a good research tangent? Really enjoyed the discussion of the headwaters geopolitics. We so often forget that water arrives at the tap only after traveling through a million tiny seeps in the hinterlands.

The State Department has got to be the most insidious federal agency.

Thanks for posting this. Bookmarked for later. Looks like another heartbreaking account of what’s occurring. We ventured briefly on the Mekong River out of Phnom Penh about four or so years ago. Tonle Sap, to the north, is also suffering, due to massive drought. As far as Cambodia goes, it appears China is ravaging the country in more ways than water, with Hun Sen’s cooperation. Near Kep there is a national park that had a chunk developed for a casino.

Just because an arm of the US government says something does not always mean that the something they said is actually wrong. China really could be pre-empting all of South and SouthEast Asia’s water even though parts of the US government say it is.

Several years ago a book written about the ChinaGov’s pre-emption of Tibetan and downstream Asian water for Chinese benefit appeared in a post and thread here. Here is the website by the author of that book . . . Meltdown In Tibet. https://www.meltdownintibet.com/

” All your water are belong to us.”

The political cartoons showing the fat, greedy Chinese could be easily redrawn to represent the US and down stream Mexico on the Colorado or Rio Grande Rivers.

If I had time, I’d grab Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac and look up his description of the Colorado River delta in Mexico before the damming of that river. Now only a salty trickle *sometimes* reaches the sea. If Canada had terminations of rivers originating in the US can there be any doubt whatsoever they would be getting only a polluted trickle (the St. Lawrence is exploited by both countries and forms a border)?

The damming of the Colorado is necessary so the US can generate electricity, grow thirsty crops in the desert and keep the cities of CA, NV and AZ liveable with plenty of water for lawns, pools and golf courses.

Who is the US to criticize any other country about dams? Practically every single good location for a dam has been built out in the US. And the electricity is supposedly “renewable” and “green”.

Eventually every single major river will be dammed. It is said the Congo River could power all of sub Saharan Africa.

Hydro-power is often cited as a ‘driver’ of dam building, but I’d wager that water supply for crop production and control of flooding are the major reasons for smaller sized dam building. Around here, in the NADS, there are lots of earthen dams which “tame” small rivers and ameliorate seasonal flooding. I could personally drive to several such earthen structures within twenty or thirty miles of where we live. One, which creates the lake for one of the gated suburbs west of town is 15 foot high and runs 1200 foot along the Hwy 98, a main thorofare. The main difference between the American experience of dams and the Asian experience I can think of is that Americans are not presently dependent upon the local waterways for personal food production. The Asians are so dependent. So, throttle an American river, ho hum. Throttle an Asian river, call out the Militia!

Over the years, some have predicted wars starting over control of water resources. Now, it is looking like a certainty.

I’m waiting for Hanoi to fund a Viet language re-make of the old war film, “The Dam Busters.”

Don’t forget motor boats and bass fishing. The Chinese may not be into that.

Needless to say many US dams have also been controversial and they even proposed one for the lower Grand Canyon but it lost out to a famous PR campaign. In the past Communist China and Vietnam have not been too friendly and once had a war. It also could be that the Chinese are just into building stuff. All those engineers need employment.

Isn’t it likely that is how many US Corps of Engineers dams got built?

The Chinese and the Vietnamese have a long and fractious history with several wars, occupations and revolts.

What worries is the Chinese practice of considering any territory ever controlled by China as fair game for a policy of China Irredenta. The present South China Sea imbroglio is bit the most visible example. Thibet suffered from that policy, and suffers still. Vietnam was under the Chinese yoke for a while back in the 111BC to 938AD period.

China still claims that Taiwan is a ‘Province in Revolt,’ thus retaining the ‘legal’ right to send in an army to subdue it.

China has been playing the Imperial card for a lot longer than America has even been around.

Nailed it here.

The early 1980s mandate to Chinese SOEs to dominate every heavy industry vertical has caused them to build massive overcapacity. They must now keep that machine at work at all costs, at home and abroad in the name of social stability and groaf, economics and practicality be damned. Xi and the CPC can’t get off the treadmill now, even if they want to. Their fear is the resource tap being shut off, hence the drive to nail down Xinjiang, the South China Sea and (if possible) Siberia.

So at home it’s ghost cities, bridges to nowhere, nuke plants replacing fairly new hydro and coal plants, and 350 (!) huge luxury resorts cheek by jowl on Hainan island.

Abroad, since at least 2008, they have underbid (at least 1/3 cheaper, always), undercut, bribed and cajoled their way into pretty much every infrastructure, energy or big dig real estate build going. They sign off on any terms, bringing full wrap offers: EPC, OEM, O&M services and both debt and equity financing, all wired together so it’s impossible to ‘fire’ any one group for poor performance without triggering repayment in full. Local partners are given lucrative ‘consulting’ contracts (payoffs by other means), but are expected to stay out of the way.

They use itinerant Chinese craftsmen on sketchy visas to perform every job above security guard and grass mowing. Managers speak only Mandarin, with the exception of a nice (usually female) factotum who speaks English. When locals protest over broken promises, they just pay off the leaders and/or the army.

While they are in theory capable of building to world standards, the moment the job is won they just ignore contracts and standards and hack along through it, copy-pasting inappropriate designs, cutting any corners they can to rush through the job; punchlists of 20,000 items are routine. But they’re also the ones fixing it. Finished projects host large scrapyards of equipment and spares that are simply abandoned to rust away. Their overuse of cement is a wonder to behold.

Pretty much every competitor who isn’t also being state subsidized has now been driven out of these markets, or have had to subsist on smaller projects whose margins are also being squeezed dry. Local authorities have grown arrogant and delusional, since the Chinese are always happy to sign off on anything. So that’s how you get 1.5 cents/kwh solar and 4 cent/mmbtu LNG (FOB).

I’m not saying all the above is some sinister Oriental plot. Whether the root imperative is profits, saving souls, or jawbs and stability, dominate or die just seems to be the inevitable consequence of massive scale deployments of capital, whether directed by private actors or state enterprises. The recklessness and rapacity of the various ‘Indies’ companies (and bubbles) from 1610 on was driven by similar ‘dominate or die’ impulses. The MIC and its overseas equivalents. Big Tech, Big Pharma, Big Ag and the PE rollups Stoller is flagging. Grow just cuz, with the blithe assumption that once you own the market you can charge the muppets what you like.

Wow. Great reply.

It’s a nasty combination of ChinaGov mercantilism and International Free Trade.

The only answer is Free Trade Abolition and Sovereign Protectionism Restoration for All Countries.

Otherwise, the final outcome will be China as the world’s industrial Mother Country and the world as China’s Tibet, I mean China’s oyster, I mean China’s hinterland

Indeed, the ChinaGov could take that position. Who/what is the US to criticize its dam building activity?

That would not make the reality on the rivers of Tibet and downstream either better or worse for the people and countries downstream from China. If they feel they have a complaint, they may well want to find other allies and supporters than the US in this affair so that the ChiCom Regime can’t play the ” hypocritical US card” against the targeted countries of downstream Asia if they raise a concern.

Interesting tangents/research – be curious to hear more about propaganda vs facts, when it comes to the Mekong. Also about Thailand, more generally (I notice Steve Keen has camped out there, during the coronavirus crisis).

Thank you for that Earthsea reference! I swear to you on my name that it’s the very thought I had when I saw the photo.

Thanks for this excellent overview.

My first introduction to the Tonle Sap (a truly amazing lake) was encountering milestones on roadsides giving two different distances for villages depending on whether it was wet or dry season. The villages float – they are built on rafts – and move according to the pulses of the lake. The people of the lake are mostly ethnic Vietnamese and they suffered particularly badly under the Khymer Rouge so they tend to be pretty reserved around outsiders.

There is little doubt that the Mekong is in deep trouble, but nobody has clean hands over it. The Thais (not just the Chinese) have been active in promoting dam building in Laos, which appears to have had as much an impact on water flows as those dams in China. The Vietnamese have allowed uncontrolled development, including massive amounts of illegal sand mining, along the delta, which is creating major potential for long term problems in the Delta, which is very much the breadbasket of Vietnam. The density of population, and the incredible fertility of the land there has to be seen to be believed.

Whatever the truth about water flows from China, there is little doubt in my mind but that the Chinese both want control over the flows, and they want those downstream to know (or to believe) that they are capable of using this control over water as an instrument of power. So I doubt if they are too upset about the US exaggerating its impact. It certainly suits both the US and China for the Vietnamese to believe that China is a threat, albeit for differing reasons.

The political dynamic is of course quite complex. In the American War, the Vietnamese sought Soviet aid precisely because they never trusted their historic rival, China, despite China providing very substantial amounts of low-tech aid. In turn, Cambodia under Paul Pot always saw China as its potential friend as they always feared the Vietnamese and this connection has continued – plus, they dislike and distrust the Thais. The Laos have tried to play each major power against each other, usually without much success – their government is deeply corrupt and has pretty much sold their country out to China and Thailand. Laos is scarcely even an independent entity anymore. The US is far less important and influential than it seems from an outside perspective – all the countries there see the US as a distant giant, only to be fought or recruited as an ally when deemed appropriate.

Increasingly, from the SE Asian perspective, the US and Russia are disappearing into the distance, China is the local big power, with Vietnam rising rapidly, with Japan and South Korea seen as big regional players, economically and militarily. Even with trade, the new EU/Vietnam trade deal has likely significantly altered local perspectives, with the US becoming relatively less important as a source of buyers.

Thailand, Vietnam, China… all seem to follow old development strategies apparently without good environmental and social impact studies that in this case might result in millions loosing a lot, famines etc.

Yes it would be difficult when what one country does may affect other countries and there is not a global approach for those assessments. I guess none of the countries you mentioned with interest and power in the region will push for some common sense.

We’d be hard pressed to find global large scale water development that does include env and socially conscious development strategies. At least none in North America, Asia, or Africa.

Agreed on all points. A good part of it is frankly that Western firms can’t offer (or conceal) the large payoffs required to secure deals of size in any EM. Anticorruption laws have very real teeth now the moment you become a ‘person of interest’. Plus everything is in the cloud or on YouTube, and multiple CEOs have been taken out, some jailed, for imprudent remarks or emails. It really ain’t worth the risks, and for big deals the Chinese just take it anyway, as noted above.

In my (finite) observation, the expats who still seem able to play with impunity are French and southern Europeans (who don’t enforce their anticorruption laws at all overseas). Oh yes, and Israel.

Aussies and Swedes also seem curiously… immune, at least so long as they’re fighting the good fight for their national champions. That’s of course always been true for Japan and Korea. Industrial policy by other means.

(It’s a good time to be semiretired, I must say)

I think that Western firms are pretty adept at paying bribes and getting around anticorruption laws. Hollywood productions in China pay enormous amounts of money under the table to shoot there. The Chinese military control the airspace and require substantial backhanders for any aerial footage. Numerous new producers are minted during any large production, to bring in suitcases of additional cash as needed.

Who enforces anticorruption laws in the US? The same entity that enforces RICO?

I didn’t realise they had to pay to shoot there, I thought it was the opposite, that China was offering all sorts of incentives to shoot.

I read recently that the movie ‘Midway’ had a weird interlude set in China specifically because some Chinese investors had insisted that some of the shooting took place there. Although it wouldn’t surprise me if the strategy is to pull productions in to the country precisely because this allows for shake downs.

This fantastic overview plays well on a link published in water cooler a week or so back aboutIndia and Chin’a water wars. China seems to be using their geography in the himalayas to take control of all major rivers originating there and making all countries downstream dependent on Chinese dictated policy for survival. A truly brilliant imperialism strategy that will have consequences beyond comprehension as the climate worsens. They’re going to fall victim to the ACOE style over building with nowhere to put the water, or will try too ambitious a project and kill millions of their own citizens, something along the lines of the north-south water project going south, possibly larger. Dams are only so good at controlling floods and given China’s history with Yangtze .and Yellow river floods they ought to be careful in their games.

> This fantastic overview

[lambert blushes modestly]

Because I like Southeast Asia, I don’t want the area to end up like Philadelphia, New York’s Sixth Borough. But these countries all have many centuries of bending and resisting Chinese pressure. So Pompeo’s strategy of throwing (to mix metaphors badly) the poisoned water of discord over water is unexpectedly smart. I don’t think the study, geopolitically, shows any of these countries anything they don’t already know in their bones, but it does give them a hook to hang resistance on.

Also, destroying Tonle Sap is a crime on the order of destroying the Aral Sea or Lake Erie, so I can see a lot of trouble-making NGOs getting involved in it.

Not to say that the Southeast Asian countries aren’t benefitting from the electric power; they are….

. . . . as Wise Old Indian once said . . . ” when the last fish is gone from the last lake in the last Asia, then the Asia Man will realize he can’t eat electricity.” or words to that effect.