By Gary Brecher. Republished from the Radio War Nerd subscriber newsletter. Subscribe to Radio War Nerd for podcasts, newsletters and more! Posted with THE EXILED.

What, you thought you were safe? You’d get through the big “Cancel Culture” war without me popping off?

No such luck.

Public morality should be pretty simple. When an oppressed group gets enough power to make its oppressors behave, they will do so — and they should.

The real problem, the kind of thing that would make De Niro in Casino groan, “Amateur night!”, starts when people imagine that they can stop immoral behavior by policing immoral characters, phrases, or scenes in literature.

They’re looking for the wrong thing. They’re sniffing for depictions of immorality, when they should be scanning the silences, the evasions.

There’s a very naïve theory of language at work here, roughly: “if people speak nicely, they’ll act nicely” — with the fatuous corollary, “If people mention bad things, they must like bad things.”

The simplest refutation of that is two words: Victorian Britain.

Victorian Britain carried out several of the biggest genocides in human history. It was also a high point of virtuous literature.

Because they were smart about language. They didn’t rant about the evil of their victims or gloat about massacring them, at least not in their public writings. They wrote virtuous novels, virtuous poems. And left a body count which may well end up the biggest in world history.

Open genocidal ranting is small-time stuff compared to the rhetorical nuke perfected by Victoria’s genocidaires: silence. The Victorian Empire was the high point of this technology, which is why it still gets a pass most of the time. Even when someone takes it on and scores a direct hit, as Mike Davis did in his book Late Victorian Holocausts, the cone of Anglosphere silence contains and muffles the explosion. Which is why Late Victorian Holocausts is Davis’s only book that didn’t become a best-seller.

Davis was among the first historians with the guts and originality to look hard at some of the Victorian creeps who killed tens of millions — yes, tens of millions — of people from the conquered tropics:

“The total human toll of these three waves of drought, famine, and disease could not have been less than 30 million victims. Fifty million dead might not be unrealistic.”

An English radical of the Victorian Era, William Digby, saw the scope of the horror: “When the part played by the British Empire in the nineteenth century is regarded by the historian fifty years hence, the unnecessary deaths of millions of Indians would be its principal and most notorious monument.”

But that didn’t happen. There was no wave of conscience among historians of the British Empire in the 1920s (or 30s or 40s or, to end the suspense, ever.)

Davis puts it bluntly: “[T]he famine children of 1876 and 1899 have disappeared.”

How did this happen? Why is it still happening? What are the lessons for those studying literature, propaganda, and ideology?

They’re very grim lessons, as it happens. While grad students comb texts for improper remarks, they miss the real point: the vast silence, and the paint-job of virtue that helps distract us.

Ideology doesn’t seem to do any good at clearing away the bigotry of Imperial history. Charles Kingsley, prominent novelist of mid-nineteenth-century Britain, was honored as promoter of socialist causes — while he wrote in letters to his wife about his loathing for the “white chimpanzees” whose corpses were littering the roadside when he visited Sligo during the Famine in the 1840s.

We go to his Wiki for a quick bio of Kingsley, and the first thing we find is “working men’s socialism.” Sounds good, right? Not if you’ve steeped yourself in the vile culture of mid-19th c. Britain. It sounds like boasting maybe, but it’s the simple truth: as soon as I saw that subhead, I KNEW, for certain, that Kingsley must have hated the Irish. And sure enough, there’s a whole subhead on his “Virulent Dislike of the Irish”:

Virulent dislike of the Irish

Kingsley was accused of racism towards the Roman Catholic Irish poor and described Irish people in rabid and virulent terms.

Visiting County Sligo, Ireland, he wrote a letter to his wife from Markree Castle in 1860: “I am haunted by the human chimpanzees I saw along that hundred miles of horrible country [Ireland] … to see white chimpanzees is dreadful; if they were black one would not see it so much, but their skins, except where tanned by exposure, are as white as ours.”

Kingsley statue in Devon. Never to be kissed by sledgehammer, because the only historical conscience the UK has is imported from the US, where no one’s even heard of Kingsley.

Someday (not in my lifetime), the UK Left will have to deal with this stuff. Your movement comes straight out of Cromwell, the Gordon Street rioters, and the Baptists, all steeped in ethnic/sectarian hate. I’m not telling you what to do, but noticing that fact would be a start.

Kingsley wrote several best-sellers after the Great Famine. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that none of them have anything to do with the Famine. These people were cunning, if mediocre; they saved the bile for private letters about “white chimpanzees.”

But it’s easy to dismiss Kingsley as a middlebrow entertainer.

Let’s take a far more serious case: Eric Hobsbawm, still revered as canonical Marxist historian of the UK. As Davis notes, Hobsbawm does “mention” the Irish Famine, but — and if any phrase ever deserves to be written in all-caps, this phrase from Late Victorian Holocausts does: “Hobsbawm…makes no allusion in his famous trilogy on nineteenth-century history to the worst famines in perhaps 500 years in India and China.”

There are no excuses for this. There are reasons, but as the song says, “It doesn’t make it all right.” Still, once the rage passes and you stop clenching your jaw ’til it aches, there are reasons. Most of all, there’s a deep Imperial skill in the trope of silence. The stupid Nazis ranted and raved and lasted 13 years, then got completely destroyed. The Empire kept its rants for private letters, passed on to a guild of coopted historians, pundits, and publishers—and has never been called to account.

Maybe it never will be. That poor optimist radical Davis mentions thought the exposé would be big news by 1925. Well, it’s 2020, and the Empire is still remembered fondly. Victoria herself is a beloved figure all over again.

Silence is the only really effective PR for a genocide, and the nature of artificial famines, as opposed to mass executions, makes silence particularly effective. Famines, most people still believe, are acts of God, or matters of chance, or perhaps (under their breath) the result of the sheer fecklessness of the victims, for being Papists as in Ireland, or Hindus as in India, or Muslims as in contemporary Somalia. After all, the Empire wasn’t standing people up against a wall and shooting them (except sometimes, as in Kenya, and the Empire handled that by putting the records on ships and dropping them into the Indian Ocean.)

Silence, not Nazi-style boasting. That’s the key. We should be looking for omissions, not gaffes. Gaffes are for hicks like Hitler. Silence is the grown-up way to hide vast genocides.

The key to effective silence is to coopt, not alienate, your intelligentsia. The hick Nazis drove out or killed their intellectuals; the Empire suborned and coddled its writers and poets, often promoting those of little talent (whose works are still vaguely canonical), adding intellectual insecurity as another motive for collusion.

Tennyson makes a good start here. Anybody associate Tennyson with genocide? Didn’t think so. He never mentioned it — in his canonical writings. He and Victoria were neighbors, chums, and he won every honor the Empire could bestow, despite being by general consent the stupidest “major” poet in the canon.

You’d never link Tennyson to genocide, until you look at his private letters and his friends’ memoirs. Then you see the perfect melding of silence and violent hatred, as in Kingsley, as in case after case after case that you never hear about — and if you do dare to mention one of the cases, will get you a grumpy, “Oh yes, we know about all that, they held some pretty objectionable opinions, as was common at the time…” (I wish I could do the inflection on “pretty objectionable.” It’s one you hear often among Commonweath academics, especially after the second drink.)

I once read Tennyson’s letters and found to my shock that he had visited Famine Ireland. Even in his letters there is not one mention of the dead. What you do get is a set of rules he laid down, as a celebrity, to his hosts as he made his way from one vampire castle to the next (never mind Mark Fisher, these guys were the real thing): he was not to be spoken to about “Irish distress,” and the window shades of the carriages in which he rode from one Ascendancy manse to another were to be kept completely shut, lest he see the bodies.

You can see why Bram Stoker, a minor Ascendancy Igor, did his best to move Nosferatu as far to the east and south as he could. As poor Byron, the one real hero of British literature, pointed out, the “moral North” always preferred to place evil as far to the east and south of Britain as it could.

So I read these letters in New Zealand and wrote to the leading Tennyson biographer, asking, “Can you explain to me why you’ve never written on Tennyson’s visit to Ireland?” He replied, “I suppose (!) because Tennyson never mentioned it.”

That, folks, is how you cover up a genocide. It’s leaked a little in the 170 years since it was successfully carried out. But it lasted longer than any other cursed tomb in history. Nowhere — not in Dublin, not in London — was there any commemoration of the Famine on its 50th anniversary in 1897, or its hundredth in 1947. In 1998 Blair gave a very carefully-worded quasi-apology, and I still remember Jeremy Clarkson’s response: “I see Blair has apologized to the Irish for poisoning their potatoes.”

In short, this method works. We are its products; we live in the delusion it created, and like it or not, Hobsbawm and a host of other Igors have that blood on their hands along with the outright vampires. Sometimes you end up angrier at the Igors than the Nosferatus.

So the key to radio silence over a genocide is cooption — very, very literal, straightforward cooption. The best candidates are novelists and poets, especially mediocre ones.

Many imperial officials moonlighted in both the active (killing) part of the genocides, and the passive PR side. Many were very popular writers, and all their doorstop books were virtuous, virtuous, oh so virtuous.

The vilest of the lot, perhaps, was Robert Bulwer-Lytton, First Earl of Lytton, the Famine Queen’s fave poet, whom she pushed for the post of Viceroy to India. After getting the post in 1876, Lytton presided over artificial famines that killed tens of millions of Asians.

No one outside India seems to mind, or even remember, that side of his life. He is remembered only as the son of Edward Bulwer-Lytton, the cuddly old silly who wrote “It was a dark and stormy night,” the inspiration of those “Worst Opening Sentence” competitions.

Lytton’s novelist father was a monster too, but he could only terrorize his family and servants. As Viceroy to India, his poet son was able to inflict, and then cover up, misery on a much more vast scale. As Mike Davis says:

“The Central Government [of British India] under the leadership of Queen Victoria’s leading poet, Lord Lytton, vehemently opposed efforts…to stockpile grain or otherwise interfere with market forces. All through the Autumn of 1876, while the kharif crop was withering in the fields… Lytton had been absorbed in organizing the immense Imperial Assemblage in Delhi to proclaim Victoria Empress of India (Kaiser-e-Hind). As The Times [of London]’s special correspondent described it, ‘The Viceroy seemed to have made the tales of Arabian fiction come true…nothing was too rich, nothing too costly.’ [This feast] ‘achieved the two criteria [set for Lytton], of being ‘gaudy enough to impress the orientals’ and…a pageant which hid the nakedness of the sword on which we really rely.’ An English journalist later estimated that 100,000 of the Queen-Empress’s subjects starved to death…in the course of Lytton’s spectacular durbar.”

But don’t expect to find anything in Lytton’s poems about these artificial famines. He wasn’t that dumb.

The poems are astoundingly dull, and the most surprising thing about the repeated charges of plagiarism that were made against them is that Lytton could steal so much decent poetry and make such complete crap out of it.

Well, he was an Earl, Victoria swooned for him, and above all, he had no more conscience than a weasel. In short, he was the man for his time and place. He fit right in there — because the Victorian elite were unquestionably the worst human beings who ever lived.

“Including the Nazis?” Yes. No contest, once the Indian and Chinese intelligentsia give us what we’ve never had: an accurate body count for Victoria’s Empire. Or, if you prefer, consider the timelines: Nazis, 13 years in power; Britain’s tropical genocides, a century at least.

What do you find, then, when you look for literary “clues to the horror” in Lytton’s poetry? Nothing. English-Department products will never admit that, if only because it precludes all sorts of Blackadder-level cunning that find all sorts of secret guilt in unlikely places like Wuthering fucking Heights. (Sorry Terry Eagleton, you probably meant well.)

These people had no conscience. Don’t waste time looking for one.

Here’s a sample of the endless “novel in verse” Lytton wrote (under the pseudonym “Owen Meredith” — not to be confused with George Meredith, a talented poet and radical who doesn’t deserve the shame of being taken for Lytton).

You really don’t need more than a sample of Lytton’s vaporous drone. Read it and sleep:

But scarce had the nomad unfurl’d

His wandering tent at Mysore, in the smile

Of a Rajah (whose court he controll’d for a while,

And whose council he prompted and govern’d by stealth);

Scarce, indeed, had he wedded an Indian of wealth,

Who died giving birth to this daughter, before

He was borne to the tomb of his wife at Mysore.

His fortune, which fell to his orphan, perchance

Had secured her a home with his sister in France,

A lone woman, the last of the race left. Lucile

Neither felt, nor affected, the wish to conceal

The half-Eastern blood, which appear’d to bequeath

(Reveal’d now and then, though but rarely, beneath

That outward repose that concealed it in her)

A something half wild to her strange character.

The nurse with the orphan, awhile broken-hearted,

At the door of a convent in Paris had parted.

But later, once more, with her mistress she tarried,

When the girl, by that grim maiden aunt, had been married

To a dreary old Count, who had sullenly died,

With no claim on her tears—she had wept as a bride.

Said Lord Alfred, “Your mistress expects me.”

The crone

Oped the drawing-room door, and there left him alone.

There was a time when I could have spun a cunning hermeneutic web here, revealing the scandalous insight that in this passage, the “Indian of wealth” has only one purpose: to die, leaving her wealth to that white guy.

But that’s grad-school crap, deserving no more than a Butthead “Well DUH, dumbass!” Orientalism has made a lot of careers and missed the big point.

That’s not the real work of poems like this. Their real point is to exist. It’s to be long, to be maudlin, and to be inoffensive to the original audience.

You won’t find gloating, you won’t see death’s heads on every officer’s cap. That stuff was for the Nazis, who were hicks themselves. The pro’s, like Lord Lytton, wrote virtuous, vapory blather like this. Reams of it. Best smoke-screen a genocidaire could want.

Lytton let 6 or 7 million peasants starve, in what had been the rice bowl of the world, for reasons which will sound familiar to readers familiar with the work of Amartya Sen — ideological, “free-market” decisions that somehow always managed to wipe out populations which had been annoying the Empire.

BTW, you can see classic port-sipping Donnish rage in sites reacting to Sen’s work, like this one.

Lytton’s callousness has been ascribed, when it gets mentioned at all, to the fact that he was a lunatic, an opium addict, a lifelong jerk, etc. He was all those things, but you’re playing into the hands of the Imperial rear guard (HQ Oxbridge and London) if you start pondering individual psychology.

As Davis says,

“[I]n adopting a strict laissez-faire approach to famine, Lytton, demented or not…[was] only repeating orthodox catechism…He issued strict, ‘semi-theological’ orders that ‘there is to be no interference of any kind on the part of the Government with the object of reducing the price of food,’ and in his letters home to the India Office and to politicians of both parties, he denounced ‘humanitarian hysterics.’…By official dictate, India like Ireland before it had become a Utilitarian laboratory…Grain merchants, in fact, preferred to export a record 6.4 cwt of wheat to Europe in 1877-78 rather than relieve starvation in India.”

“As in Ireland” indeed. The parallels between India after the 1857 “Mutiny” and Ireland after repeated rebellions are obvious, and have been pointed out many times.

In both cases it was not simply free enterprise dogma that doomed the victims: both populations were seen, bluntly put, as vermin, and many officials were not shy about saying God Himself was taking a hand to rid the Empire of them.

Indian intellectuals, from Sen onward, have been much braver than most victims in dealing with Imperial hatred of their ancestors.

After the 1857 rebellion in India was crushed, the whole culture of the Raj changed. Many early 19th c. British occupiers had dabbled in local cultures, but after 1857, this was derided as “going native.” Instead of pre-Victorian eccentrics, often brilliant and downright weird, the Raj snapped into line hard and demanded laconic, effectual mediocrity — men of few words and fewer thoughts, “men of action” whose echoes you can still hear in Wodehouse characters (always bad guys) who are archly described as “Empire-builders” or “the kind of man who made Britain what it is.”

After the 1857 “Mutiny”, the Raj repented of its brief flirtation with the cultures of the Indian center and began recruiting “frontier tribes,” especially Pashtun, who had no loyalty to pre-Conquest India. Once the Suez Canal was finished, Raj officials were able to live in a virtual Britain, dealing with Indians as little as possible:

“British contacts with Indian society diminished in every respect (fewer British men, for example, openly consorted with Indian women), and British sympathy for and understanding of Indian life and culture were, for the most part, replaced by suspicion, indifference, and fear.”

I’m going to deal with literary responses to the Irish Famine of the 1840s rather than the Indian famine of the 1870s, for two reasons —one lame, and one a little more plausible. The lame one first: I know the literature of the 1840s and 50s better than that of the 1870s. Now the reasonable one: the UK literary/intellectual world could claim ignorance of what was happening far away in India, but no one who could read a newspaper in London could claim not to know that a million people, fellow citizens of the UK, were dying in huge numbers just a few miles away.

So let’s look at the best-sellers of that era — not like poor Eagleton, desperate to find some saving grace, but coldly, seeing, as Stevens would say, “Nothing that is not there/And the nothing that is.”

A little context, for those lucky enough not to have wasted years on this very Schopenhauerian story: there were bad crops in much of Europe in 1845-50, but in most of the Continent, local organizations were able to provide some bare minimum of relief. As Amartya Sen said, lethal famines happen when shortages strike populations with no power, either financial or political. These are populations already hated by their rulers, and to put it bluntly, their rulers welcome the famines.

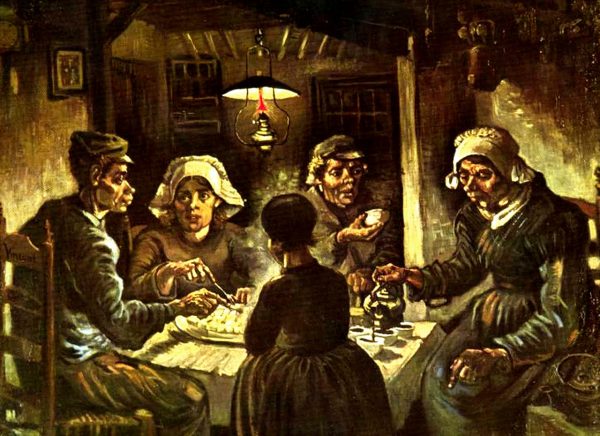

The tater, which had been imported from Peru by Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century, were the perfect slave-food. European peasants relied on the potato all across the northern tier, not just in Ireland. Ever see that Van Gogh painting, “The Potato-Eaters”?

The painting is from 1885, almost 40 years after the Potato “famine.” Europe’s poorest returned to eating potatoes, the cuisine of no-choice.

What did their potato-eating ancestors in Flanders do when the 1840s blight came? They survived thanks to local organizations that were able to limit the harm caused by crop failures:

“Flanders is a typical case where local communities carried the heaviest burden in organising and financing relief, control and repression activities. In the crisis years about two-fifths of the people in the most affected areas received some form of communal aid. In the Netherlands in 1847 18% of the people were supported by local relief boards, against 13% in 1840-1844. In some regions the numbers supported doubled. In France expenditures of the local relief boards doubled between 1843 and 1847, often financed by an extra ‘poor tax’. The same pattern is seen in South Germany.”

In Flanders, in France, in Germany, those at risk were hated only in the relatively mild way that the rich always hated the poor — a hatred tempered by the fact that the elites saw these wretches as belonging to their own group.

Not so in Ireland, in the Highlands of Scotland (which shared a history of stubborn Papism, a different language, and chronic rebellion) — or India in the 1870s.

The British elite began to nourish a particular hatred of India, especially Hindu regions of India, after the 1857 Rebellion. The uprising by supposedly loyal local auxiliaries drove the occupiers insane, in a way that would have been very familiar to any survivors of the Irish Famine of the 1840s.

In both cases, clever Imperial officials said nothing incriminating, but in the 1847 crisis, some high officials had not learned their lesson properly and said bluntly that any famine that wiped out a troublesome population was a good famine — sent by God, in fact.

Trevelyan, the official in charge of dealing with the crisis, said, “The judgement of God sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson, that calamity must not be too much mitigated.”

They talked a lot about the “moral evil of the people” as the real cause of mass starvation, and said outright that,

“We must not complain of what we really want to obtain. If small farmers go, and their landlords are reduced to sell portions of their estates to persons who will invest capital we shall at last arrive at something like a satisfactory settlement of the country.”

What you see here is free-market ideology, yes — but you can’t make the mistake of dismissing ethnic hatred as unreal, therefore not a factor. If free-market ideology had been as cold and rational as it claimed (and still claims) to be, poor people all over Britain would have been left to rot by the roads.

Ethnic hatred is real, and it exercises a real power over ruling elites’ decisions. There’s a strain of Leftist intellectual inclined to deny this at all costs, in the way that abuse victims who get religion blame their rape memories and whip scars on “Satan” rather than their stepfather.

The “socialist” polemics of Charles Kingsley are an almost ridiculously clear example of the way ideology did NOT help any Imperial writers to see what was in front of their eyes.

What did Charles Kingsley offer to the British public in 1848, when the Famine was wiping out the Irish-speaking peasantry? Ladies and Gentlemen, I offer you…drum roll…YEAST!

“Motivated by his strong convictions as a Christian Socialist Kingsley wrote Yeast as an attack on Roman Catholicism and the Oxford Movement, on celibacy, the game laws, bad landlords and bad sanitation, and on the whole social system insofar as it kept England’s agricultural labourer class in poverty. The title was intended to suggest the ‘ferment of new ideas’.”

You have to admire, or flinch, at the sheer proto-Trumpian reversal here: It’s not that our Empire is wiping out a long-hated Papist peasantry via artificial famine; it’s the Papists who are ruining our agriculture back home in England!

Kingsley’s novels contain no mention of “white chimpanzees.” He had the Imperial method: save that stuff for letters to your wife.

His real work, and I wish to God people would see this, was to write sentimental, virtuous porridge. Right through the Famine years, Kingsley wrote about every kind of maudlin nonsense he could find, the more meaningless the better. He did NOT attempt to justify the genocide. He dangled baubles in front of the popular audience instead.

How did Dickens deal with the Famine? Take a guess. Yup: “What is truly remarkable is that in the sixteen novels of Dickens, there is not a single Irish character.” That quote is from a book written long ago, unknown now.

I’m telling you — probably annoying you with my shrill insistence — that this method works.

No matter what that mush-headed crypto-Christian Terry Eagleton says, there is no trace of conscience in this list of popular novels from the Famine years or its aftermath. The nun who wrote a summary of this literature back in 1939 was more honest and correct when she said: “In the fiction of the nineteenth century by English novelists the Irishman is not a significant figure.”

There. That’s the truth.

As opposed to, oh I don’t know, yelping “She said ‘IrishMAN,’ not ‘person!” or sweating your guts out to find conscience in one of the Brontes’ novels, rather than saying simply, as this dead nun did long ago, “The works of the Bronte sisters are of imagination rather than life…” and looking for historical conscience in those sequestered imaginations — often quite viciously xenophobic, as in the caricature of the Frenchwomen in Jane Eyre — is fatuous and frankly servile.

Let’s go through a list — not my list, one I found online — of popular or ‘important’ novels from the Famine years and their aftermath:

1847

|

______ |

||

|

Wuthering Heights |

______ |

|

|

Captain Frederick Marryat |

Children of the New Forest |

______ |

1848

|

Harold |

______ |

|

|

James the Second |

serialised |

|

|

______ |

||

|

Vanity Fair |

serialised |

|

|

Mary Barton |

______ |

|

|

Yeast |

serialised |

|

|

The Saint’s Tragedy |

______ |

|

1849

|

The Caxtons: A Family Picture |

serialised |

|

|

The Lancashire Witches |

serialised |

|

|

Dombey and Son |

serialised |

|

|

Shirley |

______ |

|

1850

|

serialised |

||

|

Cheap Clothes and Nasty |

______ |

|

|

Alton Locke, Tailor and Poet |

______ |

|

|

Pendennis |

serialised |

1851

|

Mr. Wray’s Cash-Box; or, the Mask and the Mystery |

______ |

|

|

Yeast: A Problem |

______ |

|

|

Realities |

______ |

1852

|

Basil: A Story of Modern Life |

______ |

|

|

Phaeton; or Loose Thoughts for Loose Thinkers |

______ |

1853

|

Bleak House |

serialised |

|

|

Henry Esmond |

serialised |

|

|

Ruth |

______ |

|

|

Peg Wuffington |

______ |

|

|

Hypatia; or The Old Face in the Mirror |

serialised |

|

|

The Star Chamber |

serialised |

|

|

My Novel, by Pisistratus Caxton; or, Varieties in English Life |

serialised |

1854

|

The Flitch of Bacon |

serialised |

|

|

Hide and Seek; or, The Mystery of Mary Grice |

______ |

|

|

serialised |

1855

|

Westward Ho! |

______ |

|

|

Glaucus; or, The Wonders of the Shore |

______ |

|

|

Brave Words for Brave Soldiers and Sailors |

______ |

|

|

serialised |

||

|

The Shaving of Shagpat |

______ |

|

|

The Newcomes |

serialised |

|

|

The Rose and the Ring |

______ |

|

|

The Warden |

______ |

…For 1847, we have good ol’ Wuthering Heights, an S&M classic but please, nothing whatsoever to do with the Famine; Jane Eyre, another bondage classic with zip to say about all those dead peasants you could smell when the wind blew east from [that place we don’t mention].

1848: Yeast, ’nuff said.

For 1849, when every literature person knew about mass starvation in Ireland, we get two by Dickens, who as we know was so reform-minded that he never even mentioned the Irish; and The Caxtons: A Family Picture by…Edward Bulwer-Lytton, the father of Robert, Lord Lytton. Small world, Vampiria (and not by accident). Like dad, like son; Edward was a monster like his son — but in prose. The book is apparently light, comic, and utterly virtuous: “Never before had Bulwer written with so light a touch and so gentle a humor, and this novel has been called the most brilliant and attractive of productions. His gentle satire of certain phrases of political life was founded, doubtless, on actual experience.”

1850, when one might expect the genocide to be bruising tender hearts, gives us Kingsley in reformist mode with his expose of the clothing business, Cheap Clothes and Nasty. I’ve read this one; it mentions the Irish briefly, listing their presence in England, takin’ our jobs, as a result of sharp practices by merchants — not, of course, because of the suffering of the “white chimpanzees” he saw littering the roadside in Sligo.

1851. The Yeast keeps rising, which was clearly the Papists’ fault, along with other things that need not be mentioned.

1852: Kingsley again, and Wilkie Collins with Basil: A Story of Modern Life. Basil is a good book to finish on. You’re welcome to consider the other novels for 1853-55, but like the man said about the turtles, it’s Kingsleys and Dickenses all the way down.

Basil is interesting because it, alone in this decade of virtuous silence, was not a virtuous novel. Indeed, it had crimes in it, “domestic horrors” which so seared the minds of virtuous critics that they scolded Collins in his obituary, decades later, for writing it:

“The Athenaeum…called Basil ‘a tale of criminality, almost revolting from its domestic horrors’ and the Westminster Review described it as ‘absolutely disgusting’. Mrs Oliphant later called the novel ‘a revolting Story’ and the critics harked back to it even in their obituaries of Collins.”

Remember Basil, then. Remember poor Basil, lone dinghy of evil in a sea of literary virtue. Lone hint that there might be something not entirely virtuous in Britain. And hated for its lack of virtue, while the masses of virtuous pose being emptied by the carriage-load over a mass grave were, and are still, found innocent.

My hope is in the South Asian intellectuals, who alone seem to grasp how this successful model of genocide works. The Irish intelligentsia got gaslit, unfortunately, in the mid-Twentieth century and has not yet recovered. Glory to Amartya Sen and those who follow him, and my sincere apologies for dwelling on the Irish version of hushed-up artificial famine. The truth is, that’s the literary-PR story I happen to know best. You, in India, will write the true Black Book of the British Empire.

To the rest of us: stop looking for bad words. Stop taking the Nazi hicks as your example of evil. Remember Yemen. It’s virtuous silence and distraction we should fear.

Gary Brecher is the nom de guerre-nerd of John Dolan. Buy his book The War Nerd Iliad.

Subscribe to the Radio War Nerd podcast!

Read more:, Gary Brecher, The War Nerd

Ah, nobody does a great rant like The War Nerd, thanks for this.

You can still see the same literature phenomenon nowadays among a certain type of English high profile personality (especially the type who love to sell their Englishness to a US audience), of left or right, who use a high minded atheism that is essentially a cover for anti-catholicism, aka anti-Irishness (and anti-Scottish Catholics too). Note how so many English atheist comedians or academics love to make jokes at the expense of the Pope while never quite mentioning who the head of the Established Church of England might be, cos of course that might jeopardise their future ennoblement.

A point about the Irish Famine, which, it should be said, was semi-welcomed by plenty of Irish people too, was that it struck a particular subset of surplus people. The great Georgian mansions that litter the Irish landscape were paid for by wheat and barley. This isn’t because Ireland is particularly fertile for such crops – its not – but because during the Napoleonic wars Ireland was the only part of Europe with a big surplus of rural population that could be used for intensive farming. This turned large landholdings into goldmines for the aristocratic Anglo-Irish owners (plus quite a few catholic Irish too). But when the relative peace of the 19th Century returned and wheat started flooding from the US, Irish land was only useful for cows. And so a couple of million landless labourers became something of an embarrassment. Ireland lacked coal and iron for an industrial revolution (despite key inventions, such as the steam turbine having been made by Irishmen), and most importantly of all, there was no way England was going to let Ireland industrialise, so there was no way to absorb the surplus. The Famine solved the problem.

Every time I go hiking in the hills here, I can see the faint shadows of those people in faintly discernible potato beds and deserted villages at an altitude where no person should have to scrabble a living. The Irish who survived – or in some cases thrived – during and after the famine – were the small landowners and petite bourgeoisie who then built the deeply conservative and inward looking nation obsessed with symbolism and land. Those who were interested in justice were largely dead or had left to cities in Britain, the US or Australia. Its unsurprising that if you look at US industrial histories of the 19th Century it was the Jews and the Irish who were considered the biggest troublemakers (i.e. Union members).

Thanks for the on the scene report. Of course the British, and Euro imperialists in general, did get their comeuppance somewhat during WW1. But even there they took lots of Indians and Irish down with them.

As for the literary side of things, how much of the world’s great art and literature doesn’t deal with the doings and lifestyle of the high and mighty? In his series Civilisation Kenneth Clark says that by bringing us “culture” aristocrats somewhat justified themselves whereas “barbarism” is characterized by lack of culture. “Lord” Clark was conveying that Churchillian, Victorian attitude in a nutshell. He does save some praises for democracy toward the end of the series but clearly he would have been miffed to have been deprived of all that aristocratic stuff that he loved.

Man the rationalizing animal as the saying goes….nothing particularly old or new about that.

Oddly enough, I think the 18th Century Irish aristocracy were better inclined to their fellow Irishmen. They were considered ‘Irish’ by their British counterparts, so were more inclined to express noblesse oblige to them, although not so far as to allow any catholic churches near them (some were known to build Protestant churches on their lands for non-existent parishioners, just for architectural purposes. And on the subject of aesthetics, they had exceptionally high standards. Many of the long established aristocratic families did a lot for their starving tenants. I suspect the visible rise in power of the catholic church after the ending of the Penal Laws around 1820 also rattled many of them, either into becoming more generous, or into leaving the country.

The problem was that by the time of the famine many traditional families had sold out to investors or those seeking cheap titles (this is still occasionally known to happen as some lands come with titles) – many were absentee landlords, solely interested in squeezing out every penny from their lands. They were by far the most ruthless. And also, perhaps not coincidentally, they had the worst taste in architecture and art.

It’s a slight generalisation to say Ireland was prevented from industrialising. Belfast was pretty industrial (linen, shipbuilding, latterly aviation).

My great-great grandfather got out well before the famine. We don’t know anything about his life or circumstances in Ireland other than the parish where he was born. He traded whatever that may have been for the hard scrabble farming of Skiff Lake, New Brunswick, the soil of which is described here:

“New Brunswick soils are typically rocky, shallow, prone to erosion, and have low and diminishing levels of organic matter, which is important for holding the soil together and providing essential plant nutrients. In comparison to other farmland worldwide, New Brunswick has some of the most challenging soil for farming.”

My father’s rather more laconic description amounted to, “the primary crop is always rocks …”

Fortunately, he got an education, ended the generational cycle of poverty and got us out of there, for which I will always be grateful.

I’ll make a different, and much shorter point.

Look at the development of the label for imported African slaves.

Negro was the _polite_ version of colored, which superseded “black” which had the pejorative connotations that we today associate with negro (and I’m told that some older US citizens of African slave descent find “black” way more offensive than negro).

And what did changing labels achieve for the last 200 years?

Wow. Brecher is writing about sinking the canon, which isn’t a bad idea. I already had found myself highly resistant to the maunderings of 19th-century English authors, but Brecher’s discussion is a thorough indictment. (I will now try not to be too suspicious of Matthew Arnold, whose “Dover Beach” shows the emptiness of this crew.)

As a larger point, Brecher’s list points to many problems in U.S. literature: Suppression of radical novels and radical voices (early, now forgotten, Dos Passos as just one example). Glorification of the maudlin and mediocre. Currently, résumé building and the M.F.A. programs as factories for highly ambitious and irrelevant writers. Inability of theatrical works to deal with anything but middle class and bourgeois angst.

And in the US of A, we still have regular performances of The King and I, which is how a nice white lady went to Thailand and fixed everyone emotionally–while bringing enlightenment! And Oklahoma–about settling a settled land (well, those darn Indian lands don’t count).

We can keep Trollope, can’t we? The Way We Live Now is such a brilliant skewering of London financing, with bankrupt US railroad investment in the background. And the title is literally true – right now!

For anyone with Irish, or simply human, sympathies, any attempt to read Kingsley’s Westward Ho! should be made with a bucket to hand. The most saccharine apology for murdering psychopaths. Muscular Christianity, my arse. There was recently a skirmish in the Culture Wars over a town in north Devon referred to in the novel (near to a village actually named for the novel) – the media deceived its audience by not explaining what Kingsley stood for, and you can run your eye down a list of the usual facile excuses:

https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/devons-little-white-town-description-20788870

DJG, you might enjoy Anthony Hecht’s poem, “The Dover B*tch” (family blog edit)

Quite the unexpected, astringent treat for a monday morning.

Didn’t expect the rumored reason(debt obligation) of our family patriarch’s relocation to america to be a topic for todays thoughts.

Silence is truly powerful in the myriad ways it can be wielded–with many contemporary examples.

Two things really stood proud for me:

Silence is the only really effective PR for a genocide, and the nature of artificial famines, as opposed to mass executions, makes silence particularly effective. Famines, most people still believe, are acts of God, or matters of chance, or perhaps (under their breath) the result of the sheer fecklessness of the victims

and

Silence, not Nazi-style boasting. That’s the key. We should be looking for omissions, not gaffes. Gaffes are for hicks like Hitler. Silence is the grown-up way to hide vast genocides.

My mom used to confuse my younger self with her constant intoning that “Truth is what you find between the lines” and this essay is quite the extension of her logic.

I look forward to what smarter people have to say.

Another War Nerd tour de force.

Whoa. Thank you. This was spectacular. Not familiar with John Dolan (Gary Brecher) or Mike Davis. Or Radio War Nerd. So it’s nice to know it’s all out there. I had The Potato Eaters hanging on my wall for 25 years – kinda like a prayer wheel. That famine is the business model of the “free market” surprises no one these days. Our Congress, in guilt, has been as silent as British imperialists for far too long and now it seems like they resent being forced to address the realities of governance. Too bad. More of John Dolan please.

Great essay by Dolan/Brecher!

Particularly praiseworthy is his discussion of the research of Mike Davis in ‘Late Victorian Holocausts’. The books of Mike Davis are all illuminating but ‘Late Victorian Holocausts’ is probably his most important work on the brutal interface between ideology, colonialism, and ‘natural’ forces such as climate (El Niño), crop failure, and mass death.

Can’t count the number of times I’ve tried to introduce his research into discussions of ‘commie’ famines only to garner blank stares from enthusiasts of Western style capitalism—who have never heard of these mass famines under colonial capitalism.

“The nationalist not only does not disapprove of atrocities committed by his own side, but he has a remarkable capacity for not even hearing about them.” George Orwell

With climate chaos accelerating and neoliberalism the dominant ideology on the planet, ‘Late Victorian Holocausts’ also has much to say about our present disasters and our ominous future. (Would also highly recommend ‘City of Quartz’ — a detailed excavation of Los Angeles.)

https://www.versobooks.com/books/2311-late-victorian-holocausts

Nice to know that many of my ancestors would have been “white chimpanzees” whereas today I have “white privilege.” Makes the point that race is more about ideology and power than anything else.

I should pull out and reread that fascinating, yet depressing, book; of course, since it tells unfortunate reality instead of facile fantasy it was not a popular book. Much like many other books. I can recommend King Leopold’s Ghost by Adam Hochschild. Be aware that The Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad is based on the Belgian Congo while King Leopold was directly in charge of it. It is a heavy book and I am not referring to its size.

We do not officially have censorship here in the United States, but books that contradict the consensus tend to have small print runs and often disappear into the used book section to be sold at exorbitant prices. It can be hard to find a book to either check out from the library or to buy even if they are only a few decades old, with the degree of difficulty seeming to match with the amount of a book’s heresy or blasphemy.

I use to think that it was merely chance or perhaps popularity, but then I would find books written by the same writers that were far more easily found that would obviouly be less offensive to TPTB. Perhaps those small print runs are the result of those powers and not any potentially poor sales?

As someone who got a “B” in HS English Literature because I flat out refused to read any Dickens, or finish reading “Jane Eyre” and told my teacher so, I like this article a lot.*

Though at the time, my objection to this writing was not due to any moral principle… I just found the prose of mid-19th century English authors so chunky, bland, and pretentious I refused to consume it.

.

.

.

*I got enough A’s on the Shakespeare part, and the poetry parts to balance out the F’s I got on the exams related to Bronte & Dickens

The British paid writers by the word, so Dickens earned more money if his prose was drawn out. I have thought that if I had to repeat high school English, I would write a Marxist essay about Great Expectations from the servants point of view. They were the villains in the story, but I would argue they were fighting their class enemies.

Isnt the global outcry over cancel culture really just a worry about “faves” being implicated by Maxwell?

Yes, and to expand on that, it’s about the rich and powerful having to read mean comments about them from the hoi polloi in general. Billionaires and CEOs and celebrities are all used to being awful people without consequences, but now a few people call them out for their bigotry or wealth hoarding on social media and it’s “OMG CANCEL CULTURE HAS GONE TOO FAR.” Meanwhile voices for the poor, oppressed, and marginalized are routinely silenced.

Noam Chomsky yesterday on how the reason people are shrieking about cancel culture is because it targets are the powerful not the powerless:

https://twitter.com/EoinHiggins_/status/1287746116591726592

Much of the criticism of cancel culture is over people without a lot of power getting “cancelled” for making a joke, using a “forbidden” word, liking a tweet by someone who said something positive about Trump etc.

The whole “what’s the big deal, it’s just powerful people being held to account?” line is simply false and it normalizes what amounts to totalitarian thought policing. A construction worker who was filmed making the thumb and forefinger sign for ‘ok’ was fired after he was accused by a Twitter mob of making a “white supremacist gesture.” How is this okay?

Wait…now Chomsky is defending cancel culture? Didn’t he just sign a letter decrying it?

I’ve been taking a break from following all the culture war stuff…the constantly dialed up hype, hysteria and outrage are a bit much to deal with day in and day out.

Cancel culture seems to emanate from academic environments. Since the usual idea is to get someone’s job, I suspect it depends on the bourgeois framework of academia, which is authoritarian, hierarchical, and invidious, and probably partakes of the general decline of the ruling class/bourgeoisie. As things get worse, there is less to feed on; as there is less to feed on, the feeders begin to fight one another. Knock off a professor, and everyone moves up a notch.

Twitter is a sewer, and noxious fumes are to be expected, but I don’t think they will prove to have the sustained power needed to construct a totalitarian society.

While Dickens certainly does fit with this writer’s idea of the “virtuous novel” acting like a perfume to cover the “stench” of all those Irish and Indian corpses, I don’t think it quite follows with Wuthering Heights, which is a novel full of criminality, sexual obsession, abuse, violence, racism, and greed. It truly is an “S&M classic”. It lacks the sentimentality and “virtue”-orientedness of Dickens’ work, and in this sense perhaps is getting at the “dark underbelly” of English culture.

Many of the principle characters are insane in Wuthering Heights.

I mean, this is a novel where Heathcliff, the “heartthrob” of the story, goes around hanging puppies and torturing children. I’d say Wuthering Heights has more in common with “Basil: A Story of Modern Life” than David Copperfield.

One place this touches contemporary culture is Dr Who. It has an unsavoury strain of Churchill/Victoria/Union Jack Waving kitch. At the same time it wants to be seen as weightily grappling with the meaning of history. Especially the current team with stories about the Partition of India, and Montgomery Bus Boycott.

I think the untouchability of so much of English history is one reason the show has been ground into bland mush. Maybe the only fix is to have The Doctor not be British (or American, ick).

License the universe and characters to studios all around the world, it would be interesting to see an Indian, or Nigerian version, sort of like Torchwood was the Welsh take on the Dr Who universe.

Only the new stuff iirc has the flag waving. Remember the show was originally a way to get kids interested in history. Maybe by Ron Pertwee it became more straight sci-fi? The UK was not into the rah rah BS then, at least as far as Doctor Who is concerned.

Thankfully that “sci-fi is for kids crap” finally went bye-bye (ever watch the first season of Star Trek the Next Generation from ’87? Way too heavy on the Will Wheaten because sci-fi is for kids).

Just to further prove the point that you could not possibly miss the Irish famine: The Choctaw two decades removed from being force-settled in Oklahoma, heard of it and sent aid money. Something the Irish have not forgotten.

https://time.com/5833592/native-american-irish-famine/

As an aside, I was recently reading on Dickens. His writing illustrates the hell that he personally grew up in. So he was writing about the hell he knew.

I’d expect that the average American probably can’t recall anything about the Irish Potato Famine, perhaps except for the name. Silence, and its handmaiden, ignorance, or is it the other way around?

There was once an American movie, Far and Away, with Tom Cruise and his then-wife Nicole Kidman, set in the 1890s, that gave a little glimpse of life, such as it was, in Ireland, so there is that. For the cinematic-minded, here are a few more movies with Irish themes.

Not in Boston Town, my friend; it is recalled very well.

and many officials were not shy about saying God Himself was taking a hand to rid the Empire of them.

Well, let’s be fair; it was said of God “… You have shattered the teeth of the wicked.” Psalm 3:7

And thus the mystery of English (bad) teeth is solved? As a reminder of their bad history?

Great post by the WarNerd!

I always love good Bible quotes, as I don’t read the thing.

I’ve been down this path before.

Tim (Irish) You English “lost of atrocities”

Me Silence. Then “Yyes, the English did that.”

Tim: “Look of Amazement at the statement.”

Me “and I personally did none of it.”

Tim “True”

Me “It’s your round.”

I feel no guilt whatsoever for actions others took before my Grandfather was born.Nor d0 I deny them.

By the way, I believe the author missed the Diphtheria in the British run Concentration Camps which killed thousand Boers in the Second part of the Boer war in South Africa, under Kitchener’s Generalship. all to control the gold from the reef in Gautang (Transvaal).

And he might mention on Dingan and Chaka, who depopulated South Africa, or the oppression of the ‘Tswana.

When did you stop shelling out for the gilts issued in 1833 to fund compensation to UK subjects for the abolition of their property in human chattels?

There is also a good book ( name escapes me) on the atrocities that the British committed in the 1960s in Kenya.

the War Nerd NAILS it – last summer I encountered a German professor camping with his family – we got to talking about German guilt and he stated ‘sometimes guilt is a good thing’ – I started recounting the crimes against humanity committed by the English, and pointed out the role Germany continues to play as the scapegoat for the monstrous behavior of the West

the look of shock and astonishment on his face was one of the most satisfying experiences I’ve had in a long time

I presume that Becker (whose work I admire in other contexts) was having a drink with somebody who studied under Edward Said, since this is basically his point in Culture and Imperialism . The difference is that Said was a subtle literary critic, who actually believed that an understanding of the imperial background against which, say, the novels of Jane Austen were written, in turn enabled us to appreciate them more. He would have been distressed by the current fashion for sitting in moral judgement on great writers and awarding them marks out of ten for thinking like us. The truth, of course, is that great writers write about what interests them and what they are good at, not what we would later have wished them to have written about. (All those John Donne poems and not a single reference to what was taking place in Ireland at the time!)

As well as this category error, it’s important to understand how things were seen in the nineteenth century (hint: they were not like us) and how the vocabulary and concepts of radical difference and racial struggle developed, on which there is a vast literature. Oh, and give “genocide” a rest: inasmuch as the concept ever had any meaning, it disappeared with the discovery of DNA, and it’s an embarrassing historical relic when it’s not just being used as an all-purpose insult.

“it’s important to understand how things were seen in the nineteenth century”

Or in the 20th-21st century. Becker is describing what happened to Iraq in the 1990’s with sanctions.

I would add that I think Becker’s main point, that smart imperialists keep quiet, and they have a selective morality that is confined to fluff, really has nothing to do with novelists. He could have written his essay without that angle, I think. In our time we have the likes of Thomas Friedman and Madeline Albright.

I accept your first point, but I’m not taking that hint! In the previous century Edmund Burke drove himself to an early grave exposing the abuses of the East India Company, and yet the canon finds no space on its shelf for such matter. It’s as if the concerns of intelligent and compassionate people, quite apart from the terms in which they were conceived, were subject to selection by the media.

“hint: they were not like us”

That’s part of the thesis, but David can never loose a chance to demonstrate his awesome intellect in defense of the betters

“As well as this category error”

The category error is all his. Using evidence of absence as a jumping off point to lecture on the propriety of propriety is wonderfully pitch perfect smugness.

>>>The truth, of course, is that great writers write about what interests them and what they are good at, not what we would later have wished them to have written about. (All those John Donne poems and not a single reference to what was taking place in Ireland at the time!)

Good points, except John Donne wrote in the late 1500s and early 1600s, when Ireland was in some ways de facto, if not de jure, independent and the ability to get information on anything was much harder. I really can’t find any blame in him not writing about the country. The Famine of the mid 19th century happened when the country had been crushed with the native Irish being denied their native language, law, government, and customs while under a cruel, exploitative regime and news of the famine was just about everywhere.

When major writer, after major writer, does not write about ghastly horrors happening effectively next door, or being shouted in official reports, letters, and news stories, but in the privacy of their personal writings refer to the victims in vile, racists terms there is a problem. Even at the time, and during other vastly homicidal events, be it by the Spanish, British, Belgian, Dutch, or Americans there were strong, often widespread denunciations, which were usually ignored and buried, so it was not a case of being different times, different morality. It was just “decent” people being monsterous in their own personal way.

Astute of Brecher to know the best place to introduce any mention of Yemen is in the final sentence. So as to prevent (in the reader) the very phenomenon he’s writing about.

I stumbled across an Indian blog years ago, that included an essay about a British practice of using Indian children as bait for crocodiles. They tied the child to a log, and the bawling would draw the reptiles, which they could shoot. Once in a while, the kid was eaten. I don’t think you wanted the British “saving” your society, as they styled it.

In the War of the Worlds, the Martians were a metaphor for British imperialism:

And before we judge them [the Martians] too harshly, we must remember what ruthless and utter destruction our own species has wrought, not only upon animals, such as the vanished Bison and the Dodo, but upon its own inferior races. The Tasmanians, in spite of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of fifty years. Are we such apostles of mercy as to complain if the Martians warred in the same spirit?

— Chapter I, “The Eve of the War”

I find it amusing, as someone who was “educated in the canon” and graduated with a degree in English Lit, had an instinctual dislike for a great many of those titles which seemed to be nothing more than the filling of pages.

If you look at the sub- and counter-cultures of the time, you can see the same kind of willing blindness to the issues of the age. Yet each was given enough voice and positioned to give the narrative in primacy something to focus their public attention upon, to fight against.

The degeneracy of Decadence, seemingly borne of excesses of [French] opulence, still played into the same kind of identitarian narrative game that hid the true crimes of Imperial society. I would doubt if Wilde, Beardsley, Baudelaire, Huysmans, Gautier – who each experienced some form of performative oppression due to their proclivities – ever truly experienced the same kind of memory-holing discussed here.

These were all people of some relative power, with cultural capital – and even they did not take up the cause of those that were powerless. The relative tolerance of their public existence (Wilde went on a tour of the US!) compared to the absolute public amnesia about these atrocities is quite notable.

Though I know little of the others’ “proclivities” or their “performative oppression” on account thereof, Wilde was in fact imprisoned for the crime of “gross indecency” between 1895-97, during which time he was subject to solitary confinement, lost hearing in his right ear “through an abscess that … caused a perforation of the drum,” suffered rapid and apparently quite painful deterioration of his vision, and (of course) had to “performatively” kiss the well-heeled boot of heterosexual civil society by professing to have properly apprehended the “degradation” and the “madness” of his “proclivities,” as a “disease to be cured by a physician, rather than [a] crime[] to be punished by a judge.” He died of meningitis three years after his release, having famously (in circles that find such things worth remembering, anyway) written to his love, Robert Ross, “My existence is a scandal.”

You may read his 1896 petition for clemency (from which I have just quoted) here: https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/scandal/oscar-wilde-pleads-his-case

Point being: You are certainly correct in principle that identitarian scandals and cultural civil war-waging serve well enough to hide, as you put it, the true crimes of [i]mperial society. Nevertheless, you seem in a hurry to overlook the rather broad currency of the author’s particularly astute observation that:

“… hatred is real, and it exercises a real power over ruling elites’ decisions. There’s a strain of Leftist intellectual inclined to deny this at all costs …”

“Relative tolerance” is doing a lot of work here.

I have a strong feeling that someone else was ” Gary Brecher the War Nerd” before John Dolan took over that character. I don’t know how I would ever know if ” Gary Brecher” really was Gary Brecher before Dolan took over the War Nerd, but I have a strong feeling that ” Gary Brecher” began under somebody different than John Dolan.

I remember reading a “War Nerd” where the War Nerd complained about Faculty Meetings. I don’t think the Old ” War Nerd” ever complained about anything like Faculty Meetings.

So far as I’m aware, its always been John Dolan who wrote as The War Nerd, but in the earlier iterations he was far more protective of his real identity precisely because he was in paid employment at the time. Once he left that, he became more open about his ‘real’ identity. I could stand corrected on this, I don’t know much about his background.

If that is so, then John Dolan was very good at protecting Gary Brecher’s secret identity by adopting and consistently modeling a different writing style and different ideological and subject matter orientation. Though I suppose that could explain the extremeness of the sprezzaturian level of praise that John Dolan once gave the old Gary Brecher in a review-type article.

The way I see it, the older Gary Brecher/War Nerd persona was an explicitly satirical voice, taking on the character of a nihilistic, bored, and almost bloodthirsty nationalist office worker in Southern California. The satirical element is also seen in the general project of The Exile. He’s shifted away from that satirical persona a lot, I think right around when he and Ames launched Radio War Nerd, and now writes more with his actual voice.

Thank you for this. Saved the link as a reference.

There needs to be mentioned the flip side of all this silence, like the Skripal Affair, and the best one so far I think is the one you are not supposed to talk about the war! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yfl6Lu3xQW0

This led me to think about Russia, who did its own small-ish genocide of Circassians in the Caucasus at the same time.

Russian writers also didn’t write a lot about it, even though they were interested in the Caucasus as a romantic background (see Lermontov’s A hero of our time) or as an inspiration and plot source (Tolstoy’s Haji Murat). Probably it’s not fair to judge past authors by today’s standards (nonwithstanding an occasional dissident), then we would have to blame Plato for not condemning slavery.

From the results point of view the Russian campaigns were much more effective than the Irish famine. Most of the locals were driven out to the Ottoman empire and quite a lot perished on the way. If the British had achieved comparable results in Ireland, there would be a couple Irish autonomous regions covering maybe 10% of Ireland.

Ironically (or not), Russian liberals of that time considered Britain a beacon of progress and freedom at that time and quite a few dissidents moved there.

“then we would have to blame Plato for not condemning slavery”

Let me be the first then, I was horrified when I read his work.

Readying Thucydides lately, equally horrified.

On Plato and slaves and slavery. An interesting exercise is to go to Jowett’s translation of The Republic and search for ‘slave,’ then look at the passages.

Considering the ancient Persians outlawed slavery, you have every right to be horrified.

Well then you’d be horrified by each and every historical society. In case of the Persians, what about the expansionism and authoritarian rule? Surely you wouldn’t want to live in such society *today*.

I think it’s more interesting and illuminating so look at the institutions that were ‘ahead of the time’ and had a far-reaching influence, which certainly existed in Ancient Greek poleis, Persia, Imperial China and Victorian Britain.

+1 to your point re: Russian effectiveness. Is it true that Russians reduced Siberia to >10% native population?

My readings of history keep bumping up on the British and Russians and their shenanigans.

I don’t know the history of the conquest of Siberia well enough, diseases definitely played a role and there was vicious fighting in Chukotka. In some cases it was more or less voluntary, or simply a matter of starting to pay tribute to the Russian czar instead of some Tatar khan.

In general it’s more similar to the expansion of the US into the sparsely populated territories whose inhabitants for the most part had inferior weapons and organisation.

One more thing I want to mention, this one regarding accuracy.

The War Nerd (or in this case, Mike Davis) is mistaken regarding Hobsbawm, who does very much cover the 19th century’s Indian and Chinese famines (among others) in his landmark trilogy. I quote from page 162 of Hobsbawm’s “The Age of Capital”:

“The most obvious contrast between developed and underdeveloped worlds was and still remains that between poverty and wealth. In the first, people still starved to death, but by now in what the nineteenth century regarded as small numbers : say an average of five hundred a year in the United Kingdom. In India they died in their millions – one in ten of the population of Orissa in the famine of 1865-6, anything between a quarter and a third of the population of Rajputana in 1868-70, 3 million (or 1.5 per cent of the population) in Madras, one million (or 20 per cent of the population) in Mysore during the great hunger of 1876-8, the worst up to that date in the gloomy history of nineteenth-century India In China it is not easy to separate famine from the numerous other catastrophes of the period, but that of 1849 is said to have cost nearly 14 million lives, while another 20 million are believed to have perished between 1854 and 1864. Parts of Java were ravaged by a terrible famine in 1848-50. The late 1860s and early 1870s saw an epidemic of hunger in the entire belt of countries stretching from India in the east to Spain in the west. The Moslem population of Algeria dropped by over 20 per cent be tween 1861 and 1872. Persia, whose total people were estimated to number between 6 and 7 million in the mid-1870s, was believed to have lost between I and 2 million in the great famine of 1871-3. It is difficult to say whether the situation was worse than in the first half of the century (though this was probably so in India and China), or merely unchanged. In any case the contrast with the developed countries during the same period was dramatic, even if we grant (as seems likely for the Islamic world) that the age of traditional and catastrophic demographic movements was already giving way to a new population pattern in the second half of the century. ”

Anyone interested in an overview on Hobsbawm, there is a recent article in NYRB covering his biography. I have read several of his books, the trilogy, but was impressed by this account of his background and intellectual acuity.

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2020/07/23/eric-hobsbawm-clear-inclusive-lasting/

Gary, I’ve been impressed with your work in the past, and this is no exception: it’s excellent writing about history, educating your readership.

But I fear that you’ve misunderstood the -point- of these protests, about “cancel culture”. It’s not to revisit the past: it’s about ongoing injustice, and the ways that that is *justified* and buttressed by a certain reading of the past. Do you really think that statues of Robert E. Lee would *matter* if Black Americans were full citizens? If they didn’t suffer under the oppression of a totalitarian police state that can snuff out their lives in an instant?

C’mon, man.

It’s been a few years since, I read Willkie Collins’ Moonstone. He portrays both Evangelicals and Colonial officers in an unfavorable light. He’s sympathetic to Hindu holy men. I won’t spoil the story, so I won’t give out any more details. Willkie is also something of a feminist. The heroes of three of his novels are bold young woman, trying to clear their name or receive their rightful inheritance.

wow, so much research here, so much buried knowledge, thanks.

Ditto. Silence… Obfuscation… Misdirection… For me, this post amplified and expanded on the observations of Rebecca Solnit at the brainpickings website that was linked here on NC recently:

…”To name something truly is to lay bare what may be brutal or corrupt — or important or possible — and key to the work of changing the world is changing the story.”…

…”There are so many ways to tell a lie. You can lie by ignoring whole regions of impact, omitting crucial information, or unhitching cause and effect; by falsifying information by distortion and disproportion, or by using names that are euphemisms for violence or slander for legitimate activities… Language can erase, distort, point in the wrong direction, throw out decoys and distractions. It can bury the bodies or uncover them.”… “Such naming of wrongs, betrayals, and corruptions unweaves the very fabric of the status quo.”

https://www.brainpickings.org/2018/10/18/rebecca-solnit-call-them-by-their-true-names/

I have mixed feelings about this. Dolan is effectively setting up a straw man—taking aim at a Victorian Studies that hasn’t existed since the late ‘90s at best. If you’re at all familiar with the field, you’ll know that takedowns like this aren’t just common currency, they’re something like the dominant take on VS in North America right now. There’s a piece in the LARB, “Undisciplining Victorian Studies,” doing the circuits at the moment that does something very similar to what Dolan does above. The authors of all of these takes have to, of course, try and insist that they are marginal and insurgent voices valiantly speaking truth to an oblivious and racist discipline, but it’s all academic theatre—the equivalent of pushing on an open door.

Something about the tone of this piece makes me think that the knife in the back of the discipline is personal for Dolan, though. Although the moralising is rather odd coming from a Sadean.

“I have mixed feelings about this. Dolan is effectively setting up a straw man”

Please elucidate your feelings on straw men. It doesn’t seem you have mixed feelings at all about them or this piece. It seems like you don’t like straw men or the piece.

“Something about the tone of this piece”…He’s IRISH!!!!!!!

I’m not at all familiar with the field.

And I find your take to be pretty stank. Insider ball from pissy academics.

I agree with you. This is revisionism of a kind we’re getting all too familiar with these days. Pardon the long rant that follows:

While you can’t be a NC regular without getting a steady diet of uncomfortable anti-imperialist look-in-the-mirror (and thank you!), I found this piece far too breezy and Twitterish (sick burns by me boyo on those pompous Anglo Saxons!), given the very broad and heavy accusations it levels.

Look, I’m not going to argue the tragic facts on the ground. Lessons of History: Awful stuff happens when societies become, or are made, fragile. (Magnified in places like India which geography already renders subject to regular weather disasters). Don’t let it happen to us! Fair enough, check.

….But this piece comes across as an ‘I can top that’ barroom rejoinder to the Woke crowd by one of the many autodidact historians who prop up the history wargaming boards I also frequent. (We were evicted from our ‘ole in the ground!)

1. Like the 1619 and 1491 ‘projects’, it heaps harsh summary judgment on those who cannot now answer and, in the prevailing moral fashion these days, unto their descendants. Shame! Your prosperity is a blood libel, built upon heaps of Our skulls! (Now where’s our Reparations? with an extra cut for us spokespersyns, of course)

2. Revisionism also feeds a new cycle of bigoted myths that won’t end any better than our own did. Why aren’t We Chinese / We [light skinned] Indians / etc. ruling most of the world, given our manifestly superior culture and work ethic? Because [white men] divided, looted and then did their best to kill us all! So we now feel free to crush Tibet / Kashmir, and devour the planet because Century of Humiliation!

3. The central conceit of the piece conflates Sins of Commission with ‘Sins of Omission’. Yeah, well that was all pretty much the same to the 1944 victims in Belsen and Bengal, I hear you say.

But what is that, the Eichmann defense? (Well over half of the ‘work’ was done quite quickly, we only worked and starved *some* of them to death).

As bad as Nazi effing Germany! Really? Or at best, not notably different from meticulously engineered assembly line slaughter of entire selected populations.

4. You see, prior intent does count here, as well as actual capability of the accused to choose and direct a different course of action once the disaster unfolds. Malign neglect and depraved indifference toward economically marginal ‘savages’ or surplus labor are culpable, certainly, and that is the universal legacy of imperial systems. Lessons of History, part 2, check.

But that *is* materially different from programmed industrial mass slaughter of peoples who (mostly) weren’t economically peripheral, but lay at the core of the civil society.

And the (numerous) instances of the British practicing actual programmed mass killing (e.g. 1790s Ireland, Croppies lie down) are not materially different in scale from the practices of other empires, white and brown, before and since. The rolling Mughal conquests in India from 1520 on made the post 1857 repression look sedate (e.g. it was they who gave the British the idea of executing mutineers using cannons). But whataboutism, rah-jah….

5. As it’s impossible to prove a negative, on the Sins of Omission questions, it’s easy to practice 20/20 hindsight, backdating morality, cherry picking of anecdotes, and a host of other fallacies. From there, it’s a simple matter to ‘prove’ that no evil has arisen in the world since [date] that [insert group of choice] has not been either directly culpable for, or else equally culpable for failing to prevent or remedy. Evil! Condemn! Cancel! Year Zero!

6. Now, the point about Victorian society being uneasily aware that Very Bad Things Were Happening and yet collectively choosing to avert its eyes is more interesting, though still reductionist. Victorian values are bourgeois, and the bourgeoisie is a profoundly psychological herd animal. Perhaps that’s at the heart of why Irish got airbrushed out of literature as such, I don’t know. It’s a good observation though, and made the piece worthwhile.

Dietrich Dorner’s ‘The Logic Of Failure’ offers some useful insights on human unwillingness to confront or engage in crisis. But they have little to do with some tacit Victorian agreement that the mass death of inconvenient people was really best for all concerned, now have some more tea and crumpets, as the author proposes.

First, actual unawareness of what was in motion, at least until each crisis was in full swing and irremediable. We’re seeing all that right now with Covid, and as we all know here, the disaster isn’t nearly finished yet. The world was far ‘bigger’ in the 19th century; even Ireland was a day’s sail away at best. India, whose geography predisposes her to a regular variety of weather extremes, was 6 weeks away until the telegraph, and even then dimly comprehended even by the Englishmen who had visited. Like today, the extremes are just overwhelmng. Where does one start?

Second, what’s in front of your face takes priority over what isn’t: English cities packed with Irish migrants seeking work in dark satanic mills, and breeding like rabbits. They don’t seem starving to me; what, you want to bring in more of them? Are you quite entirely mad? I don’t honestly care why they’re coming over, no more please.

Third, for those in situ who actually bore witness, actual helplessness in the face of unfolding disaster. Which usually manifests in: shock; denial; blaming some other incompetent or malign party; blaming the victims and, as noted, sometimes rationalizing that it’s all for the best anyway; plus avoidance behaviors that give the illusion of ‘control’, e.g. microfocusing on your model of a rebuilt Vienna in the bunker, etc. Again, lessons of history. People get overwhelmed, and intent ceases to count.

So none of this is a matter for pride, but nor does it add up to a collective Wannsee conference.

…. Anyway, if you are determined to hate on the Anglosphere root and branch, these comments won’t stop you. Reach your own views. I hope they are interesting to some.

TL:DR there are other ways to look at this history that fall between Godwin’s Avenger and Huzzah! Up the Empire denialism. Human, all too human.

Why? Your defense of the Brits could just as well serve as the defense of the R2P crowd who say “sure hundreds of thousands of Iraqi’s died but we didn’t Intend that to happen.”

Perhaps the real reason the Holocaust gets so much emphasis these days is not so much the methodical murder plan of its creators as that it happened to middle class people–people like us–as opposed to faceless natives who “have not” those Maxim guns. It’s popular these days to say the Germans got the whole idea from the Reconstruction South with its racial laws but arguably they were heirs more to the mass murder forms of exploitation of the European century that preceded. The Victorians and other European imperialists had their own racial theories to justify what they did with some Malthus and Darwin thrown in.

I agree that moralistic theories of history–or anything really–should be viewed skeptically but if we are going to see human behavior as a kind of universal, a beast that must be tamed, then only the results are what counts.