By Wolf Richter, editor of Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street.

Six months into the Pandemic, restaurants that haven’t given up yet are still in survival mode. In many places, dining outside has been allowed for weeks or months. That’s a problem for restaurants that don’t have any space outside. In other places, indoor dining is allowed, but only at reduced capacity, which is a killer in the tough restaurant business.

One restaurant owner who is doing fairly well – he has a corner restaurant in San Francisco with wide sidewalks on both sides, and all his tables fit outside – told me that a sushi chef he knows with a tiny sushi place that seats only a few people switched to takeout, and suddenly there were no more limits to how many people he could feed, and his business boomed, and he hired another sushi chef to keep up.

There are a few winners. Those that manage to be open and have enough room outside are busy and hard to get into. Others restaurants gave up.

Inside dining at restaurants in California can start on Monday, but only at 25% or 50% of capacity, depending on county. No restaurant can survive for long operating on Friday and Saturday nights at 25% or 50% capacity.

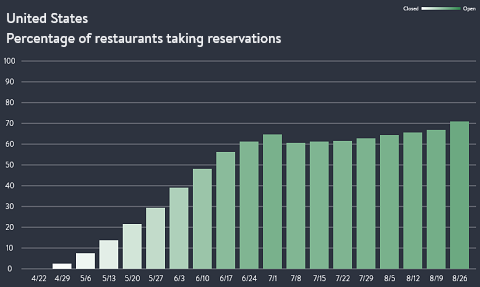

In the US, about 75% of the restaurants that took reservations before the pandemic are now taking reservations again, up from zero in April, according to data from OpenTable which provides online reservation services for 60,000 restaurants. Back on July 1, already 65% of the restaurants were taking reservations again, but then new outbreaks spreading across the country, particularly in the South, triggered some retrenching (chart via OpenTable):

The “seated diners”

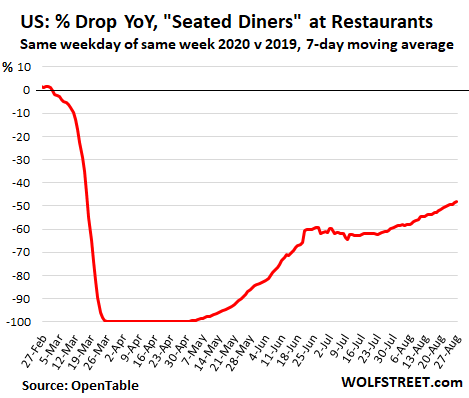

Another measure, “seated diners,” shows how many people actually sit down in restaurants to eat, drink, and be merry. This is a measure of the business volume restaurants are doing.

OpenTable provides data on seated diners, whether they’re walk-ins or had made reservations online or by calling, based on a broad sample of 20,000 restaurants that shared that information with OpenTable. It compares daily “seated diners” on the same weekday in the same week last year.

Overall for the US, there was the plunge to -100% (meaning zero seated diners), then the recovery, then the resurgence of the virus that caused some backtracking, and a renewed but more gradual recovery. Six months into the Pandemic, “seated diners” on August 27 were still down 47% from the same weekday in the same week last year (year-over-year, seven-day moving average):

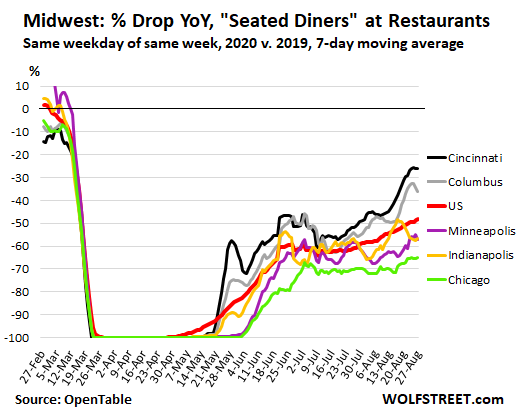

Cities in the Midwest:

The chart below shows five major cities in the Midwest for which OpenTable provides data. The bold red line is the US average for reference. As of August 27, the number of seated diners is down the least in Cincinnati (-26%, 7-day moving average), and down the most in Chicago (-65%, 7-day moving average):

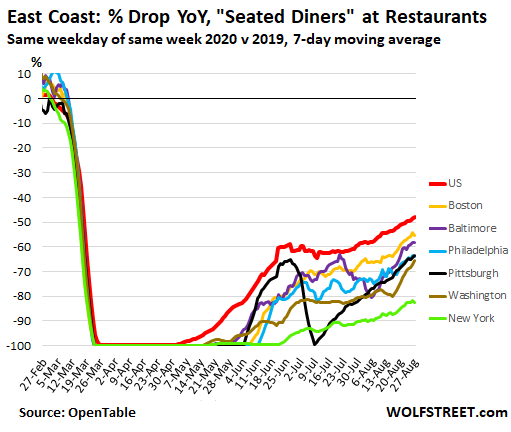

Cities on the East Coast:

Pittsburgh is an interesting case (black line in the chart below). If you want to find a letter for the type of recovery in Pittsburgh, it would be two letters: the “LN-shaped” recovery.

First, the plunge in seated diners in March; then the flat part when they remained closed; then the recovery starting in early June. But soon, Covid cases surged, amid indications that people partying in indoor venues were infecting each other, and then infecting others afterwards, and by early July, restaurants were shut down again. This caused the number of seated diners to plunge briefly to zero (-100%), before restaurants could reopen. But this phase of the recovery has been slower, and the 7-day moving average as of August 27 is still below where it had been in late June.

New York City’s daily number of seated diners is still down 83% (7-day moving average), a notch higher than San Francisco and Honolulu, which we will get to in a moment:

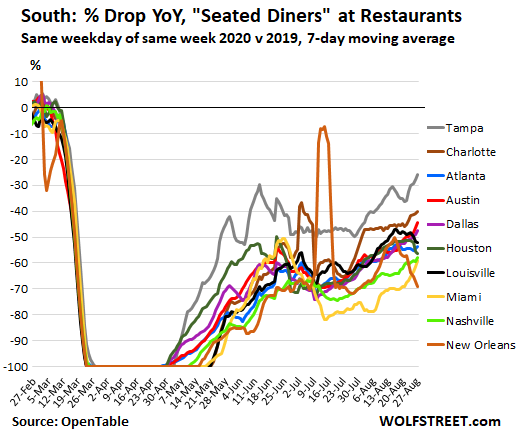

Cities in the South:

The chart of the cities in the South is kind of wild – in part because of New Orleans (spiky brown line). And it has to do with Hurricane Barry last year.

On July 10 and 11, 2019, most restaurants in New Orleans shut down as Barry was heading for the Louisiana coast. So in the year-over-year comparisons of seated diners, the daily number for July 10 and July 11, 2020, when quite a few restaurants were open, spiked respectively by +83% and +140%. The 7-day moving average smoothened out the spike somewhat, but it remains huge — a result of a hurricane last year and not a major city-wide food-extravaganza this year:

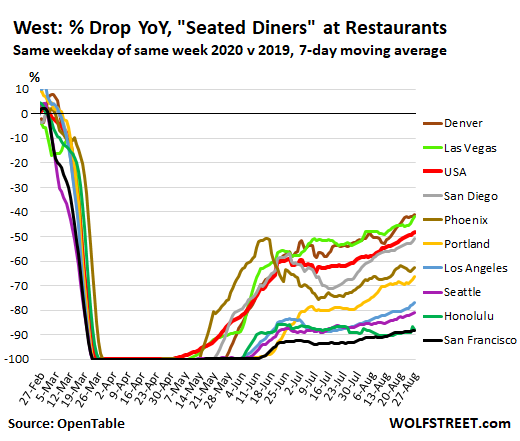

Cities in the West and Hawaii:

There are two cities in the West and Hawaii where restaurants are worse off than in New York City: San Francisco and Honolulu. For both of them, the 7-day moving average of seated diners is still down 88% year-over-year. Both of them are big tourist destinations. Some tourists are driving into San Francisco, and a few are flying in, but not many. And Hawaii has essentially shut down its tourist business. So tourist-focused restaurants face that additional problem.

Al-fresco dining in San Francisco is limited by lack of sidewalk space or parking space for many restaurants. The City closed a few streets to traffic, so that restaurants there can offer outside seating, and that’s wonderful and vibrant and a lot of fun. But it’s not enough. Starting next week, there will be some limited indoor dining, and the curve should tick up further, but this recovery is going to take a long time (US in bold red):

All this data from OpenTable is based on restaurants where you can make reservations, not fast-food restaurants. They’re pricier than fast-food restaurants, and the staff is often specialized and fairly well-paid, including from tips on tickets that can be hefty. Most of the food and liquidity these restaurants serve originated in the US.

Money spent in restaurants mostly stays in the US, unlike money spent on consumer goods that are imported from another country. So stimulus money spent in restaurants does more for the economy, particularly the local economy, than stimulus money spent on imported gadgets (and eating in a favorite restaurant is food for the soul in these trying times).

Lambert, the post did not completely copy through. I’m not sure if this was on purpose or not.

If there is a bad second wave this winter, which is widely feared, I’m afraid that many of these restaurants may not make it.

One area that seems to be doing well is pizza delivery.

https://fortune.com/2020/08/12/coronavirus-food-trends-takeout-delivery-pizza-dominos-covid/

The same is true for many food delivery companies like Uber Eats.

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-uber-results/uber-rides-take-covid-19-hit-but-food-delivery-business-doubles-idUSKCN25230X

Pizza delivery may be economically viable, but I’m not as sure about Uber Eats. Plus the fees they charge tend to eat into the already thin margins of many restaurants.

They also have a history of treating their drivers poorly and underpaying drivers.

Winter is coming. Al fresco dining works in the south after mid-October, but not in most of the north. If restaurants north of, say, the 40th parallel (Kansas-Nebraska border in the middle, Orgeon-California border in the west, and Harrisburg, PA area in the east) are struggling in September and don’t have a robust take-out model, then they are unlikely to make it to the spring. The warm areas of the south are much more likely to have surviving outdoor restaurants and bars over the winter.

A number of restaurants have closed for good in our Upstate NY area, and we have had a fairly mild Covid-outbreak (looks like the bad parts of Canada, not the rest of the US). There are a number of good places that were able to set up solid takeout business as that was already part of their model. A lot of people frequent them, as much to give them business as anything else. One pizza truck that does high-end Neapolitan-style pizzas has done a booming business, even getting hired to come to neighborhoods for a pizza day.

I make a point of picking up or using places that have their own delivery precisely to avoid participating in the screwing of restauranteurs that Uber Eats and its ilk represent.

I’ve not eaten inside a restaurant in 6 months and have done drive-through maybe 5x in that time period.

We get the 100 days of 100 degrees here in the summer, and the prospect of dining outside is simply daunting. Can’t imagine how it would be in hades, er Arizona.

And then in the winter we get Tule Fog in the Central Valley floor, which can make 54 degrees feel like 41 when you’re outside.

Do these YoY seater diner percentages include closed restaurants?

I think they look at total reservations etc., so it should.

I’m sitting on the deck of one of the rarities in the restaurant biz, one that is doing exceptionally well in this age of Covid.

Their numbers are up over any previous year, their key being on the cusp of the wilderness, and everybody wants to get away.

Seconded. Lots of people still trying to get outside and out of the cities. What happens at the end of tourist season?

The resort closes for the year in late October and reopens in late May.

The manager told me that she thought 80% of those staying here this summer had never been to the area, and once you’ve been here-you’re hooked.

@Wobbly

If I am reading the charts currently, the % decline is total for a city, not an average of within-restaurant declines. I wonder what the drop in $ is.

It’s interesting to see Las Vegas so high. I’d think that part of the decline in New York, etc is due to no more tourists or business lunches. If Las Vegas is only down 40-50% then maybe tourists weren’t visiting the local restaurants

So, my city, probably like lots of yours, invested tens of millions of dollars to help spur generally upscale micro-niche restaurants over the past decade as a way to attract the creative class, who we were told needed world-class food options. Restaurants boomed, though of course, so did inequality in my city.

This is now food for the soul and important local spending? I guess for a certain class it is.

Same thing happened here in Tucson. To the extent where we were declared a UNESCO City of Gastronomy.

All well and good, but I can’t help thinking of other industries that also are worthy of investment. Like the development of solar-powered energy generation technology and technologies relating to water harvesting and water conservation.

Higher end dining generally provides much higher wages. Think workers not who they serve

For how many? Think workers and who they serve.

Can restaurants be used as a bellwether for the wider hospitality industry: car rental, hotels and motels, theaters, pools, recreation centers, and amusement parks? I don’t know much about restaurants, but I do know hotels.

In my neck of the woods, i.e. the Kansas City Metro area, some hotels are closed up with what looks like some permanence. Others are struggling at occupancy rates between 5-10 percent. Some smaller boutique hotels that cater to an upscale clientele are doing better, and in that cohort, one or two are nearly back to normal, mainly because of sharp marketing to a devoted clientele. But overall, things look kind of sucky for most hotels and people who live off tips.

One factor that determines whether a hotel lives or dies in these times is the depth of the owner’s pocket.

There are properties that operate on the slimmest of margins, the investors extracting as much as they can from the operation. These are people who are in it for the money only. If there was more money to be made operating laundries or or insurance agencies, they’d be in that. The hotels that seem to be succeeding and likely to survive are those operations headed by a devoted hotelier backed by deep pockets.

Around the middle of October, Kansas Citians start moving indoors, unless there are heaters or fires. Might be a good time to start a service that rents propane heaters to restaurants!

Reduced occupancy hurts most businesses. If they rents were lower, many more of them could survive. Evicting current struggling businesses to try and replace them with new businesses that ALSO can’t afford current rents just adds an extended vacancy and remodeling expenses to the problem.Of course most of the landlords have mortgages to pay. If those were lower, they could survive on the lower rents that businesses can afford to pay. But with interest rates already super low, landlords can’t get meaningful mortgage relief through lower interest rates. Of course when the leases and mortgages were written there weren’t any provisions to lower them. I think that what we actually need, is a massive fall in commercial real estate prices, as painful as that is. As terrible as that would be, it may well be our least bad option to put the economy onto a supportable basis.