By Lambert Strether of Corrente

Most of you will be familiar with the concept of “crew change”; that’s what happens, for example, when your flight gets delayed because the pilots or cabin attendants have worked more hours than the FAA allows them to, and the airline needs to swap in a new crew. This happens rarely, but imagine crew change failures happened simultaneously for many, many aircraft across the entire network: You’d have the airline equivalent of a traffic jam, or even gridlock, and no flights would move. A similar process is happening in real life, now, but for ships, not aircraft. Because the Covid pandemic has made crew changes very difficult, many ships and crew (about 300,000) are stuck in port, stranded, unable to move. The New York Times headline, “Trapped by Pandemic, Ships’ Crews Fight Exhaustion and Despair,” captures the humanitarian issues very well; the body cuts to the economic chase: supply chain risk.

But the Covid-19 pandemic led countries to start closing borders and refusing to let sailors come ashore. For cargo ships around the world, the process known as crew change…

“This floating population, many of which have been at sea for over a year, are reaching the end of their tether,” Guy Platten, secretary general of the International Chamber of Shipping, which represents shipowners, said on Friday. “If governments do not act quickly and decisively to facilitate the transfer of crews and ease restrictions around air travel, we face the very real situation of a slowdown in global trade.”

But crew change is not as easy as it might seem. Again from the Times:

Leaving a ship, and getting home, requires more than just disembarking. It usually involves multiple border crossings, flights with at least one connection, and a slew of certificates, specialized visas and immigration stamps. A crew member’s replacement has to go through the same steps.

Every step in that procedure is “broken” because of the pandemic, with flights limited, border controls tightened and many consulates closed, according to [Frederick Kenney, director of legal and external affairs at the International Maritime Organization, a U.N. agency that oversees global shipping]. While some countries have found ways around the problem, “the rate of progress is not keeping up with the growing backlog of seafarers,” he said last week.

In this post, I’ll look first at the supply chain risk. Then I’ll look at the institutional issues that have hitherto prevented this risk from being addressed, and the crew changes from being made. (These issues, besides the pandemic itself, involved government, but even more the complex business structure of international shipping. Finally, I’ll look at proposed solutions, which must be international and intergovernmental in nature, and must also — quelle horreur — involve the owners of the assets, the ships. (I’m going to skip the humanitarian aspects, but imagine a powerless worker from Sri Lanka or the Phillipines, trapped on board the same hulking metal ship for many months with nothing to do, with an expired contract, money owing, perhaps in debt, with no access to anything onshore including health care, and a family at home. Seafaring has always been a brutal trade, but the workers’ situation during the pandemic is really beyond the pale.[1])

Supply Chain Risks

Shipping investors, led by Fidelity, have cleared their throats and let it be known that the crew change situation must be addressed. From the Financial Times, “Fidelity warns of supply chain risks due to stranded seafarers“:

Fidelity International, the $566bn asset manager, has called on companies and governments to urgently address an unfolding crisis in global supply chains as hundreds of thousands of ship workers remain stranded at sea because of the pandemic.

Jenn-Hui Tan, global head of stewardship and sustainable investing at Fidelity, said an estimated 90 per cent of world trade relies on shipping, providing a vital service for businesses and consumers. He said seafarers should be classified as essential workers and allowed to disembark.

Matters are not so simple as Tan suggests, but the scope of the problem is real. Bloomberg, in a deeply reported article, “Worst Shipping Crisis in Decades Puts Lives and Trade at Risk“[2], concurs:

The crisis has begun to reach shipping investors including global asset manager Fidelity International Ltd., American insurance giant Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Co., asset manager Oaktree Capital Group LLC and finance titan JPMorgan Chase & Co. If it isn’t resolved soon, analysts say, it threatens to ripple up the supply chain, affecting commodities companies like Cargill Inc. and Glencore Plc. and retailers like Dick’s Sporting Goods Inc., just in time for the holiday shopping season.

Note, however, that Fidelity et al. have not actually proposed doing anything themselves. What will it take for force action? From an interview this month with Bjørn Højgaard, Chief Executive Officer of Anglo-Eastern Univan Group in Hong Kong, in BIMCO’s house organ, “Governments will act when supermarket shelves are empty“:

[HØJGAARD:] We are at a breaking point. If sentiments swing, which I fear is starting to happen, and the seafarers start saying no to signing yet another extension, it only takes a few days, maybe a couple of weeks before you have large parts of the world fleet unable to move… I can see the dominos starting to fall and the global supply chain being severely affected, the seafarers are not striking; they are simply at a breaking point. Suddenly, the ships are not going anywhere. They are taking up places at berths, preventing other ships from arriving to discharge and load, and, in a very short period of time, I can see the dominos starting to fall and the global supply chain being severely affected. But we must understand that the seafarers are not striking; they are simply at a breaking point because their legal entitlements to leave are being denied them.

Parenthetically, here again we see the enormous power that, er, “essential workers” in the supply chain have.) As we shall see, a few seafarers are striking. And it’s not all up to government, or at least shouldn’t be. With that, let’s turn to institutional issues.

Institutional Issues

Issues seem to fall into three buckets: national governments, the business structure of international shipping, and unions. (There are also international agencies involved, as we shall see in the “Proposed Solutions” section, but they seem to be driven by the previous three institutions, and are not the drivers.) Let’s look at each in turn.

National governments.

Requirements imposed by national governments — to be fair, for the perceived safety of their own citizens — have made crew change extremely difficult. From Bloomberg:

Of the commercial ports in 123 countries and territories, 45 have stopped allowing crew changes, according to Wilhelmsen Ships Service AS, part of the border closings and quarantine requirements that have come to define coronavirus containment policy. Seventy-six allow seafarer swaps with restrictions and two permit the changes with appropriate documentation. Until the world’s ports reopen, shipping companies say, it will be hard to relieve large numbers of workers.

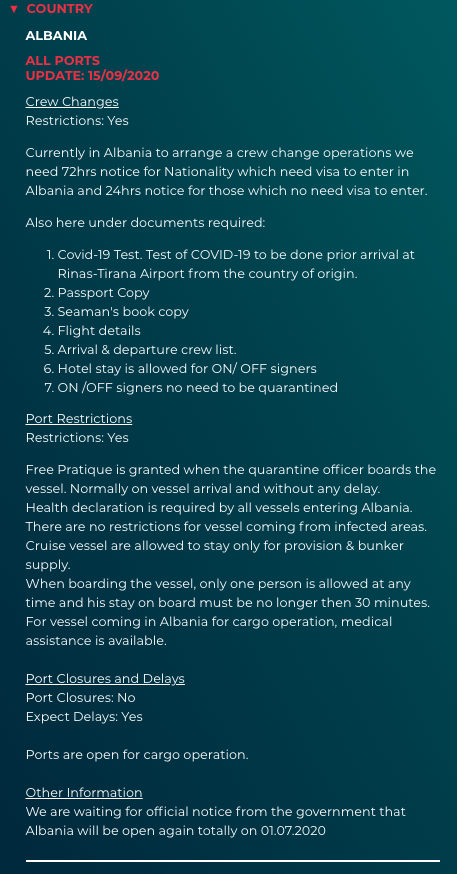

Even if all the ports were to reopen tomorrow, crew change would be difficult, because the regulations are insanely complex, and differ from country to country. There are various sites that purport to aggregate all the rules; here is one, and here is another. Here is what requirements for a crew change look like for Albania (first one the list):

Yikes. (The insane complexity of the rules has also led to an insanely complex network of brokers and service providers, as we shall shortly see.[3]) But there are further obstacles. In a pandemic, rule changes can be arbitary and verbal. From Seatrade Maritime News, “Crew change crisis: a global perspective“:

“The regulations are changing by the day. As there’s limited written information, the predominantly verbal communications present a challenge for us in guiding customers,” commented Johan Thuresson, GAC Dubai’s General Manager – Shipping Services.

Nor is it necessarily possible to get seafarers on their way, even if the paperwork is complete, due to governments having imposed international flight restrictions:

In some areas, crew changes had become almost impossible in practical terms due to the closure of many airports, including those in Jordan, Lebanon, Guyana and Panama, for varying periods. Throughout the pandemic, the chaos that followed widespread international flight restrictions has been widely discussed.

“The limiting factor is the amount of flights available for seafarers to get home in a timely manner… and visa expiration for non-EU crew,” said Tom Hanoy, Operational Manager at GAC Norway. In Hanoy’s experience, Filipino seafarers been particularly badly affected.

And then, of course, there is corruption. Again from Seatrade Maritime News, “Crew changes at India’s Vizhinjam port stalled by local agent“:

Crew changes on ships at Vizhinjam port, on the southernmost tip of the Indian peninsula, have been stalled by the muscle power displayed by a local steamer agent, which has set up its own association to carve out a monopoly on the activity.

(Of course, corruption might well be made to work in favor of crew changes, but that would require money from the asset owners.)

Business structure of international shipping

Bloomberg describes the nature of the industry:

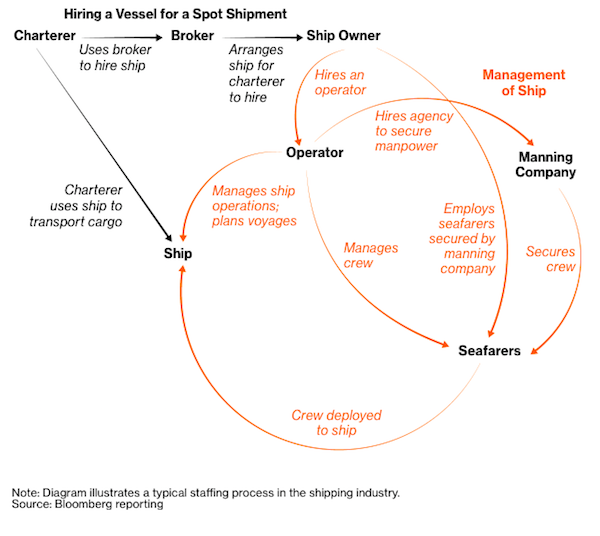

Modernity has made shipping safer, but seafarers are still at the mercy of an industry that is opaque, deeply fragmented and bound by a patchwork of national and maritime laws. Every ship is connected with a handful of separate entities. Typically, there’s the ship’s owner, its operator, a staffing agency which recruits seafarers, and the charterer—the company that hires the boat to get its goods from point A to point B.

There are a few dominant players in the shipping industry, but much of the trade is made up of middle men upon middle men, connecting companies that have goods to ship with a vast network of owners, operators, staffing agencies and so on. Those layers make it hard to hold anyone accountable for on-board working conditions, says Richard Meade, managing editor of U.K. shipping researcher firm Lloyd’s List, or to solve problems when they arise.

At the furthest remove, investors and money managers have built lucrative portfolios out of shipping assets they almost never have to touch.

They provide a handy diagram:

So to whom, exactly, does the seafarer go to seek redress for their crew change issues? One would think, it hope, that it would be their union, so let’s turn to them.

Seafarers’ unions

As Bloomberg shows, there is in fact a body of law meant to protect seafarers:

Ratified by more than 80 countries, the Maritime Labour Convention isn’t mere guidance—the agreement sets minimum working conditions for seafarers that underpin the insurance policies and global contracts that govern the transport of basically everything. But the ongoing pandemic has shattered the norms of this highly fragmented industry, and with countries wary of relaxing port and border restrictions, violations of worker protections have become common. Nearly 20% of the world’s 1.6 million seafarers are stranded at sea and…at the mercy of employers and shifting quarantine requirements to get them home.

The fragmentation of the business makes it very hard for unions to take advantage of the legal rights their workers have. Here is what it wook for one staffer of the International Transport Workers’ Federation to free seven workers from Myanmar.From the International Transport Workers’ Federation, “Companies must take crew change opportunities in the UK and elsewhere” (I’ve helpfully underlined the institutional players):

The repatriation of seven Myanmar crew members from a Korean-owned vessel via the United Kingdom shows that crew change is still possible during the crew change crisis, but it requires the determination of the seafarers’ employers, says Liverpool-based ITF Inspector Tommy Molloy. In addition to working with the ship’s owner and management company, securing repatriation for seafarers often involves contacting government agencies in the port state (where the ship is docking) [the UK’s Maritime and Coastguard Authority] and in the flag state (where the ship is registered) [Marshall Islands]…. In addition, [Molloy] contacted Embassy of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar in London, to flag the plight of the seafarers…. Molloy went on, “The Embassy advised that whilst there were no commercial flights into Myanmar, there were ‘relief flights’ with limited seat availability… It took a lot of communication between the various parties to finally get the seats confirmed. I was able to call contacts in UK Border Force – with whom I have been able to develop an excellent working relationship – and the crew members were given clearance to remain in the UK until they could board their flight.”

Again, for seven seafarers. Do the math for 300,000. With the best will in the world, I don’t see how the unions can help very much[4]. Now let us turn to solutions, which involve two institutions not yet mentioned: International agencies, and the asset owners.

Proposed Solutions

Once again, what’s the hangup? Returning to Bjørn Højgaard:

Hjgaard believes the only reason this scenario has not played out yet is that, despite the seafarers being overdue for crew change, shipping has continued to deliver. With 90% of global trade transported by ships, however, the situation is fragile. We still have energy and food being delivered, and because there are no consequences for us all, it is easier for politicians to prevent crew change from happening in their country, in their ports. They dont think it matters. But at one point, it matters.

There seem to be at least two organizations acting in advance of the crisis. The first is a combination of union, employer, and trade groups. From Splash 24/7, “First global tripartite initiative to support countries for crew change gathers momentum“:

The International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) and the International Maritime Employers’ Council (IMEC) have jointly contributed $500,000 to the Singapore Shipping Tripartite Alliance Resilience (SG-STAR) Fund to support countries that adopt best practices for crew change. This adds to the S$1m ($737,000) SG-STAR Fund established by the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA), Singapore Shipping Association (SSA), Singapore Maritime Officers’ Union (SMOU), and Singapore Organisation of Seamen (SOS).

Progress is needed on ways crew can show their negative Covid-19 test results

First I’ve seen Covid testing addressed, so I assume it’s the elephant in the room. More:

Besides ITF and IMEC, the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) will also lend support to the SG-STAR Fund including technical expertise in shipping.

With the contribution and support by ITF, IMEC and ICS, the SG-STAR Fund is the first global tripartite initiative bringing together like-minded international partners from the industry, unions and government to facilitate safe crew changes. The fund, based in Singapore, will be disbursed for use upstream in countries where seafarers come from. Like-minded partners are being sought to join this new global alliance.

Since its founding three weeks ago, the SG-STAR Fund has been working with seafarer supplying countries such as the Philippines and India on key initiatives, which include the accreditation of quarantine and isolation facilities, Covid-19 PCR testing certification, white-listing of clinics for PCR testing, digital solutions for tracking crew change, and interactive training sessions for crew to help them understand crew change procedures and guidelines.

All very well, but $1,237,000 doesn’t seem like very much money, does it?

Next, there is the International Maritime Organization. Their “Joint Statement on the contribution of international trade and supply chains to a sustainable socio-economic recovery in COVID-19 times” should get the attention of asset owners:

[T]he delivery and availability of essential products such as food or medicines became a common challenge undermining countries’ capacity to respond to COVID-19 and begin to sustainably recover. Preliminary data and forecasts indicate severe impacts on economies worldwide, for example:

- Inland transport volumes may fall by up to 40 per cent in 2020 in the panEuropean region,

- Freight transport volumes may reduce by up to a half by the end of 2020 in most parts of Asia,

- Value of regional exports and import is expected to contract respectively by 23 and 25 per cent in Latin America and the Caribbean,

- Total losses in the revenues of airline companies from the Arab region are estimated in 2020 at about US dollars 38 billion (some 53 per cent of 2019 revenues),

- African airlines may lose over US dollars 6 billion of revenue and the contribution of the industry to the GDP of countries on the continent may drop by US dollars 28 billion. Moreover, 3.1 million jobs linked to the industry are at risk on the continent.

In view of the preliminary data and the lessons learned from the pandemic so far and in order to drive socio-economic recovery and to become more resilient and sustainable, supply chains require a more effective coordination, cooperation between the transport modes, and across borders.

I’ll say. And they propose the following:

The Joint Statement outlines a series of 15 different and related measures that Governments must take, including:

- designating seafarers as ʺkey workersʺ providing an essential service, to facilitate safe and unhindered embarkation and disembarkation from their ships;

- undertaking national consultations involving all relevant ministries, agencies and departments, to identify obstacles to crew changes, and establish and implement measurable, time-bound plans to increase the rate of such crew changes;

- Implementing protocols for crew changes, drawing upon the latest version of the Recommended framework of protocols for ensuring safe ship crew changes and travel during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic;

- refraining from authorising any new extension of seafarers’ employment agreements beyond the maximum period of 11 months, in accordance with the MLC, 2006; and

- facilitating the diversion of ships from their normal trading routes to ports where crew changes are permitted.

So, er, governments may “facilitate” the “diversion of ships,” and “travel” may be “ensured,” and new contracts signed (since the old ones may no longer be extended), but who will pay for all that? Why, that would be the asset owners:

“The people who own the assets and make money off the assets need to come together to come up with a solution,” [Andrew Kinsey, a New York-based senior marine risk consultant at Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty] said. “They have to use their assets to get the crew off. Each party needs to assume responsibility instead of passing it to the next party.”

Of course, passing the parcel of responsibility from one party to the next seems to be what the business structure of international shipping is designed to do; see again Bloomberg’s diagram.

Conclusion

So, will the asset owners stump up? Well, Fidelity didn’t say anything about that….

NOTES

[1] Crew stress and exhaustion also has deletorious effects. From Bloomberg: “‘This is the most dire situation with vessels and crew that I’ve seen in many decades,’ said Andrew Kinsey, a New York-based senior marine risk consultant at Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty. At best, he says, expect more detentions and delays. At worst, there will be disastrous mistakes—Allianz estimates that human error contributes to at least three-quarters of shipping industry accidents—and fatalities.”

[2] Tellingly, the URL differs from the headline: 2020-pandemic-shipping-labor-violations. So that’s how the reporters see the issue, no matter what the editor said when they wrote the headline.

[3] Rather like ObamaCare.

[4] Absent a general strike.

I hope the seafaring crews themselves end up recovering from all this hardship. But I also hope that the shipping industry can not solve this crisis in time to save shipping.

I hope a major death-blow can be dealt to international shipping, enough to comprehensively exterminate the International Free Trade Conspiracy and its Forcey Free-Trade.

Sounds like a Trump vote to me. Nationalist

Not necessarily. I voted for Trump last time in order to prevent Clinton from getting elected. I felt Trump posed a lower threat of thermonuclear exchange with Russia than Clinton would have. Also Trump might disrupt the International Free Trade Order somewhat.

On the down side, Trump has appointed the typical normal Republican Ferengi Biznissmons to head the various departments and agencies. They are political commissars sent to destroy the existence of those agencies so comprehensively that no pro-governance successor can ever bring them back. And that poses risks and dangers of its own.

And Clinton isn’t going to be President. A Joemala Administration will restore antiRussianitic antiRussianite antiRussianism as a major basis of DC FedRegime foreign policy. But a Joemala

Administration won’t bring Clinton’s insane level of personal hatred and psychotic cackleness to it.

So do I fear another Trump term more than I loathe and despise a Jomala Administration? Or do I loathe and despise a Joemala Administration more than I fear another Trump term? ( One thing to remember is that a Joemala Administration will do its best to keep Joe ” Uncle Fester” Biden in office for two years plus a day before trying to replace him with Kamala, so that Kamala would be eligible for ten years of a President Kamala if things work out that way.

So . . . 12 years of Them versus 4 years of Him. Decisions . . . decisions. . .

Without a course correct, Harris isn’t winning in 2024. Obama was relatively popular and a good campaigner, and his margins in the EC weren’t jaw dropping and came off historic turnout. Harris isn’t getting that treatment.

> the shipping industry can not solve this crisis in time to save shipping.

Well, masks come from all over the world. I don’t know where the capital equipment for mask-making machinery comes from, but I suspect primarily not the United States. (A Google search on “where are melt blown fabric machines manufactured”? comes up with two solid pages of Ads (!!).

So, autarchy, but not yet, oh Lord, not yet.

Thank you for explaining this. We needed to replace a refrigerator, but because of supply chain problems, we were told by a couple of local appliance stores, the new fridge (not a particularly expensive or rarefied model) would not arrive for a couple of months. So far we are three weeks in and over a month to go, limping along with a hotel room size 3.5 cubic ft fridge/freezer we were able to buy right away. Started worrying about other appliances that are of same vintage and whether we had to plan ahead to replace them. Wanted to get an all-electric induction range. Checking the big box stores online, we found that earliest date we could expect the range to be delivered was December 28. I’ve been wondering ever since about the nature of these supply chain problems and how bad things might get.

> We needed to replace a refrigerator, but because of supply chain problems, we were told by a couple of local appliance stores, the new fridge (not a particularly expensive or rarefied model) would not arrive for a couple of months.

When looking for bottom-of-the line printers, I found that at least one vendor was completely out of stock. Now I know why.

Have any other readers experienced odd shortages like this?

For months now I’ve been hearing people in businesses ranging from furniture and bike sales to construction talking about fears that things are going to gum up by the end of the year as stocks are being run down and not replaced and calls to suppliers aren’t getting returned – and this is before you apply potential Brexit problems. I get the impression (this is completely anecdotal) that lots of shops were promised normal deliveries ‘in the autumn’, but that the actual date keeps get pushed back further and further.

Last night I was talking to a Chinese friend and she mentioned that lots of her friends here (typically Chinese, nearly all of them have some sort of side business in buying and selling arbitrage to and from China) are worried about non-deliveries of even quite basic products, and things seem to be getting worse, not better.

This is definitely a leading indicator of supply chain damage to both the UK and EU ahead of transition end for the UK in December 2020.

I’m.guessing that for the EU its every member state for themselves as it most definitely is for the UK.

Quite how the current mêlée of shipping issues will add to a hard brexit is hard to comprehend.

Here (NZ) I’ve noticed empty shelves of whisky in several seemingly non-associated shops in town. Figured it was probably that they were running lower stock levels, but since it was disproportionately among the cheaper brands, this is a far more logical explanation …

stock up, chaps!

Chicken wire, paddle boats, life jackets, galvanized stock tanks.

In the class of “first world problems” the hot tub cover I ordered in mid-June has yet to arrive …

People, people! What you are identifying is a market lack, IOW, an opportunity. Bikes and bike parts are not high-tech, nor are refrigerators. If all that money wasn’t going to CEO bonuses, just imagine what an economic powerhouse we could build!

For instance, my local hardware store (part of a co-op) cannot get replacements for the 4″ little paint rollers they sell. Solid foam tube with a hole down the middle, not high tech!! Bike brake and gear cables, that’s a meter of aircraft cable and some silver solder, not high tech!! Why can’t we make things anymore? Have we become the Marching Morons?

As long as we have Forcey Free-Trade, we can’t build anything. Any parts-replacement industry we tried to rebuild here would be massively underpriced by semi-slave-labor parts from all the worst anti-social anti-standards pollution-havens of the world. Those are where the Corporate Globalonial Plantationists have relocated all the parts production . . . to their Import Aggression Platforms.

Only a new trade regime of Militant Belligerent Rigid Protectionism would allow America to rebuild any ghost of any powerhouse again.

Free Trade is the New Slavery.

Protectionism is the New Abolition.

I feel like Lambert’s explainers in particular (and NC as a whole) are actually a new genre: context with interspersed examples from a variety of different text forms, graphics, and perspectives. It reminds me of Bakhtin’s notion of heteroglossia …”a dialogically agitated and tension-filled environment of alien words, value judgements and accents, weaves in and out of complex interrelationships, merges with some, recoils from others, intersects with yet a third group: and all this may crucially shape discourse, may leave a trace in all its semantic layers, may complicate its expression and influence its entire stylistic profile”. …In this sense, a hyperlinked grandchild of the novel form. But is there a shorter word for this?

> is there a shorter word for this?

“Blog post.”

707!!!

Would this be a good time to bring up the subject of autarchy again? Right now I am glad that I live in a country that is food self sufficient and in a state that supplies most of its vegetables.

Also, I loved how some the quotes kept mentioning that the crews were not striking as it that was worse thing than what was already happening. I don’t doubt would love to bring back large scale international slavery to prevent such ills as strikes or threats to their profits

> I don’t doubt would love to bring back large scale international slavery to prevent such ills as strikes or threats to their profits

It looks like the complexity of the hiring process accomplishes more or less the same thing. The owners of the gig economy companies could learn a thing or two from the ship owners, I think.

I imagine the owner are thinking robots, but I dunno. When a robot ship crashes, or sinks, or burns, it would be a lot worse than when a robot car does. And no doubt there are insurance issues.

I don’t know if we could have pure autarchy in all things. But we could have autarchy in some things and semi-tarchy in most things.

But we can’t get there from here without robust protectionism.

Is there any chance that the accident in Mauritius has something to do with this? How long had that crew been at sea?

> Is there any chance that the accident in Mauritius has something to do with this? How long had that crew been at sea?

No, according to Trade Winds, “Master and crew of grounded bulker off Mauritius were not caught up in crew change crisis.” Before the pay wall kicked in:

The crew change in the context of commercial aviation is likely going to be a result of government regulations not an employment contract. For example, the applicable standards in the US are under 135.265 of the FAR’s.

“(a) No certificate holder may schedule any flight crewmember, and no flight crewmember may accept an assignment, for flight time in scheduled operations or in other commercial flying if that crewmember’s total flight time in all commercial flying will exceed—

(1) 1,200 hours in any calendar year.

(2) 120 hours in any calendar month.

(3) 34 hours in any 7 consecutive days.

(4) 8 hours during any 24 consecutive hours for a flight crew consisting of one pilot.

(5) 8 hours between required rest periods for a flight crew consisting of two pilots qualified under this part for the operation being conducted.

(b) Except as provided in paragraph (c) of this section, no certificate holder may schedule a flight crewmember, and no flight crewmember may accept an assignment, for flight time during the 24 consecutive hours preceding the scheduled completion of any flight segment without a scheduled rest period during that 24 hours of at least the following:

(1) 9 consecutive hours of rest for less than 8 hours of scheduled flight time.

(2) 10 consecutive hours of rest for 8 or more but less than 9 hours of scheduled flight time.

(3) 11 consecutive hours of rest for 9 or more hours of scheduled flight time.

(c) A certificate holder may schedule a flight crewmember for less than the rest required in paragraph (b) of this section or may reduce a scheduled rest under the following conditions:

(1) A rest required under paragraph (b)(1) of this section may be scheduled for or reduced to a minimum of 8 hours if the flight crewmember is given a rest period of at least 10 hours that must begin no later than 24 hours after the commencement of the reduced rest period.

(2) A rest required under paragraph (b)(2) of this section may be scheduled for or reduced to a minimum of 8 hours if the flight crewmember is given a rest period of at least 11 hours that must begin no later than 24 hours after the commencement of the reduced rest period.

(3) A rest required under paragraph (b)(3) of this section may be scheduled for or reduced to a minimum of 9 hours if the flight crewmember is given a rest period of at least 12 hours that must begin no later than 24 hours after the commencement of the reduced rest period.

(d) Each certificate holder shall relieve each flight crewmember engaged in scheduled air transportation from all further duty for at least 24 consecutive hours during any 7 consecutive days.

The terrible crash in Tenerife was partly caused by the KLM pilot being in a hurry to get up and away before their duty hours were exceeded.

– One thing to note though is that there are as yet no duty hour limits on maintenance personnel that I am aware of so it’s not unheard of of for mechanics to end up pulling many hours of overtime or back-to-back shifts and as a result performing some pretty critical work while sleep deprived.

I used the airline example of “crew change” as an analogy from the reader perspective. I did not argue that the legal regime or the union contracts were the same.

Highly recommend reading this book for an inside look at life on board a cargo ship. https://www.amazon.com/Ninety-Percent-Everything-Shipping-Invisible/dp/0805092633

Also, some years ago, John McPhee wrote one of his typically excellent books: https://www.amazon.com/Looking-Ship-John-McPhee/dp/0374523193

Both are well worth your time.

That Dollar Store is full of cheap stuff that ain’t so cheap. I live near a major port and am somewhat familiar with this issue:

“Ballast water discharge typically contains a variety of biological materials, including plants, animals, viruses, and bacteria. These materials often include non-native, nuisance, exotic species that can cause extensive ecological and economic damage to aquatic ecosystems, along with serious human health issues including death.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ballast_water_discharge_and_the_environment

Move enough of these ships and their ballast around and you will have a great exchange of global flora and fauna with unintended consequences. And I would imagine, mutations. Note the mention of viruses and bacteria!

Another issue with these ships is ownership. Most of these ships are set up in financial structures that protect the owners from liability if there is a disaster. In Mauritius, for example, I have read a few articles but seen nothing about ownership. And, like all things financial, there is little regulation. These ships are not owned by Mom and Pop. So, giant ships prowl the planet with the ability to create immense disaster.

Which then raises the question: is all this Global Trade a good idea? Obviously, the Global Trade model does not take into account the Disaster Factor and the Ballast Factor. If the Father of Free Trade Ricardo were alive today, he might rethink his main idea.

The larger principle at work here is that Humans engage in activities without assessing ALL the consequences. Full steam ahead to the Mother of All Icebergs.That probably is not going to end well in our current endeavours with Biotech, Nanotech, GI, AI, etc. But, what the hell, it makes a buck.

When I was a small child, we lived not far from what were then called “The Docks” in London, and from time to time we would walk down to the Thames to watch the ships coming in from all over the world.

These ships were owned by national companies, very often British in those days (my father worked for one) who recruited and trained seamen and officers. There was a special school near Waterloo for aspirant officers. In those days, crews of the (massive) British fleet went out with the ships and came home with the ships. This changed from the 70s onwards with the arrival of container ships and sophisticated electronics, and the de-skilling of maritime commerce generally.

What’s interesting is that an old system which was simple and flexible has been replaced by one of such baroque complexity as is described above. It’s typical of a world economic system which has become not only much more complex, but infinitely more fragile, as a result of the ceaseless search for “efficiency”. It’s a strange kind of efficiency where nobody really knows who’s responsible for what, and where one small bug can stop the whole system dead.

>that’s what happens, for example, when your flight gets delayed because the pilots or cabin attendants >have worked more hours than they are contractually obligated to do, and the airline needs to swap in a >new crew.

Lambert, this is not the reason they have to change crews. (If it was, they could just pay overtime.)

The reason is that the FAA sets time limits on how long pilots can work (it’s called “flight duty periods.”) It’s for safety reasons. This is also the reason that long-haul overseas flights (e.g.,US to Singapore) will have a relief pilot on board. See: https://thepointsguy.com/guide/how-pilots-stay-alert-long-range/

Corrected!

Bottom line? If you haven’t already acquired, or at least ordered what you need long term, hunker down with what you have…..and learn to adapt. This is going to be the longest ride of your life.

PJ

This is in error. The crewmembers are still working and getting paid, they are just burned out. They need to go home.

Also a consideration is that the crewmembers need to remain in good graces with the crewing agency. If they don’t, they won’t get future work.

And, there are the replacement crewmembers stuck at home, no work, no earnings to support their family.