Yves here. Although the reinforcement of the neoliberal frame (“consumers” as opposed to “citizens”) is irritating, this study of the impact of stimulus payments debunks the idea that helping the poors makes them lazy.

By Olivier Coibion, Associate Professor, UT Austin; Yuriy Gorodnichenko, Quantedge Presidential Professor, Department of Economics, University of California – Berkeley; and Michael Weber, Associate Professor of Finance, University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Originally published at VoxEU

A major component of the 27 March CARES Act in the US was a one-time transfer to all qualifying adults of up to $1200, with $500 per additional child. Using a large-scale survey of US consumers, this column studies how these large transfers affected individuals’ consumption, saving and labour supply decisions. Most respondents report that they primarily saved or paid down debts with their transfers, with only about 15% reporting that they mostly spent it. On average, individuals report having spent or planning to spend only around 40% of the total transfer. The payments appear to have had no meaningful effect on labour-supply decisions from these transfer payments, except for 20% of the unemployed who report that the stimulus payment made them search harder for a job.

Amidst the rising spread of COVID-19 and the pervasive imposition of lockdowns in March 2020, the US Federal government passed the CARES Act on 27 March 2020. This stimulus package was exceptional both in its size (over $2 trillion in allocated funds) and in the speed at which it was legislated and implemented. A major component was a one-time transfer to all qualifying adults of up to $1200, with $500 per additional child. Model-based estimates suggest that the fiscal multiplier might be as high as 2, but so far little is known how household consumption responded to the fiscal transfer (Bayer et al. 2020). While the 2001 and 2008 fiscal stimulus payments provide some guidance (Shapiro and Slemrod 2003, Agarwal et al. 2003, Johnson et al. 2006, Parker 2011), the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 shock, the associated uncertainty about the length and severity of the pandemic, and the widespread prevalence of lockdowns which restrict in-person shopping make it ex-ante unclear how individuals used their payments.

Stimulus Cheques and Household Consumption and Savings

Using a large-scale survey of US households, in Coibion et al. (2020) we document that only 15% of recipients of this transfer say that they spent (or planned to spend) most of their transfer payment, with the large majority of respondents saying instead that they either mostly saved it (33%) or used it to pay down debt (52%). When asked to provide a quantitative breakdown of how they used their cheques, US households report having spent approximately 40% of their cheques on average, with about 30% of the average cheque being saved and the remaining 30% being used to pay down debt. Little of the spending went to hard-hit industries selling large durable goods (cars, appliances, etc.). Instead, most of the spending went to food, beauty, and other non-durable consumer products that had already seen large spikes in spending even before the stimulus package was passed because of hoarding.

Effects of Stimulus Payments on Behaviour

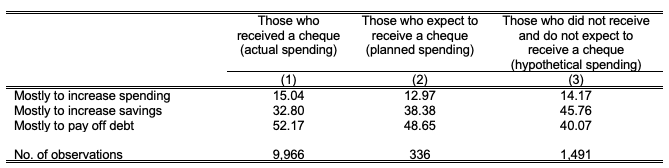

We report in Table 1 the response of households to the qualitative question of how they used their stimulus payment: mostly spent, mostly saved, or mostly to pay off debt.

Table 1 Distribution for the use of stimulus payment, qualitative.

Notes: the table reports the distribution of qualitative responses for the use of stimulus payment.

Column 1 focuses on the 90% of households in the survey who have already received their payment. Only 15% report that they mostly spent their transfer, even lower than the corresponding values found after the 2001 and 2008 transfers. One third report that they primarily saved the stimulus money, leaving over half of respondents answering that they primarily used the Treasury transfers to pay off debt. Column 2 presents equivalent shares for survey participants who anticipate receiving a cheque but have not received one yet. They report very similar plans to those who have already received their payments: only 12% plan to mostly spend it while more than half plan to use it primarily to pay off debt. Even those who do not qualify for a stimulus payment report similar answers when asked hypothetically what they would do if they received $1,000 from the Federal government: 14% report that they would primarily spend the money. However, a larger share of these individuals report that they would save the money rather than pay off debts, likely reflecting the fact that most of those who are ineligible for stimulus payments are higher-income and are less likely to be constrained by debt levels. Jointly, these qualitative responses suggest that the stimulus payments had only limited effects on spending.

In addition to qualitative questions, the survey asked participants to assign specific dollar values to different ways they used (or would use) their stimulus payments, including saving, paying off debt and different categories of spending. On average, households report having spent approximately 40% of their stimulus cheques, with the remaining 60% split almost evenly between saving (27% of stimulus) and paying off debts (31% of stimulus). Relatively little of the spending went to large durable goods or medical care (7% and 6%, respectively). Instead, most of the spending was on food and personal care products (16%) or other consumer products (13%).

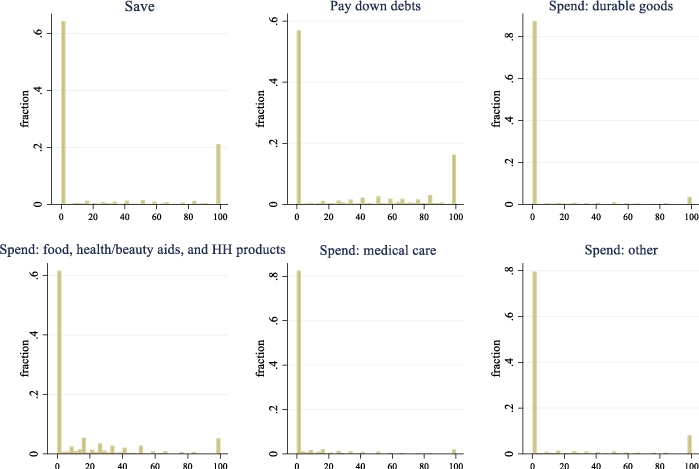

Figure 1 shows heterogeneity in marginal propensities arises to most categories of using stimulus funds. For example, a little over 20% of respondents saved all of their stimulus cheques while over 60% saved none. Similarly, ≈15% of individuals reported that they had used all of their payment on paying down debt, while nearly 60% used none at all for this purpose. Spending categories are similarly dispersed: almost 90% report that they spent none of their stimulus payment on large durable goods, and 20% claim that they did not spend any extra money on medical care or other consumer goods.

Figure 1 Expenditure share for stimulus payments (effectively marginal propensities)

Notes: each panel in the figure reports the distribution for the share of stimulus payment used for saving, paying off debts, and consumer spending.

Which individuals tend to spend their stimulus payment? The question of identifying consumers whose MPCs are higher matters not just for the effectiveness of stimulus packages but more generally for understanding economic dynamics, as emphasised by Kaplan and Violante (2014). There are a number of observable factors that make it more likely that a respondent mostly spent their stimulus payment. For example, men are a little more likely to spend their cheques than women, although the difference is small in economic terms. African Americans are much more likely than whites to primarily pay off their debts, whereas Hispanics are less likely to pay off debts and more likely to spend the payment. Additional factors that make individuals more likely to spend their cheques include being out of the labour force and neither owning a home nor renting (e.g. living with parents). Finally, those who received larger payments (even after conditioning on household size) are less likely to spend their payments and more likely to save them. Given how large the COVID-related stimulus payments were relative to those in 2001 or 2008, it is consistent with consumer theory that a larger fraction would be saved compared to previous experiences.

Another source of economically large differences is liquidity constrains. Constrained households spend 10% more than unconstrained ones, which is allocated mostly to additional spending on food/beauty/personal products and medical care. We also see that those who lost earnings due to the COVID pandemic use about 5% more of the stimulus to pay off debt and 4% less to increase savings, and also spend relatively more on medical care but less on other consumer products, suggesting that their lost earnings were preventing them from getting all the medical services that they needed. We find little role for individuals’ macroeconomic expectations.

Respondents were also asked about how stimulus affected (or would affect) their labour supply decisions. The vast majority (90%) of the employed report that it had no effect on their labour supply decision. About two-thirds of those that are unemployed reported that it had no effect on their job search decision, while over 20% report that the stimulus cheque led them to search harder for a job. In short, we find evidence that some unemployed workers increase their job search effort in response to stimulus payments but otherwise find no meaningful evidence of labour supply effects from the CARES Act one-time transfers.

Conclusion

Sending money directly to households has been one of the main components of US stimulus packages in the last three recessions. We provide some of the first estimates for transfers to US households put in place under the CARES Act. US households only spent around 40% of their stimulus payments but there is significant heterogeneity in terms of how different individuals respond. Many spent their entire stimulus payment, and just as many saved their entire cheque or used it to pay off debt.

See original post for references

How many still have stimulus money after a few months and how many don’t? That would be more informative about people’s financial stability.

Just how long do you think $1200 lasts?

I spent my stimulus money on weed, wine and whipped cream, the rest I just squandered.

A fine homage to George Best

I gave half to food banks. The remainder went toward purchase of an electric guitar (American made). We are retired and in good shape with our pensions – military and DoD civilian retirement, 2X social security plus wife gets a German pension (she is Korean).

Rock on, Robert!

Would like to see income distribution of the observations, and then broken down by spend, save, pay debt.

Pay down debt? OMG! That’s downright un-American.

Just think of all those poor payday loan places, finance & c.c co’s. They must really be suffering…

I put the $1200 in the bank, thinking the government would somehow use it to screw me later. But I was able to do that because the state of Pennsylvania gave me $300 in food stamps instead of the usual $15.

I think I used $30 of COVID-cash to buy a single skein of expensive hand dyed sock yarn to knit, but broadly, we used our tax refund and stim cash (which arrived nearly simultaneously) to refi our mortgage and pay off a car note a year early. So I might not have stimulated the overall economy but my personal economy is MILES better at a time when we are all blessed to still be employed.

My mom is still sitting on her $1200 because she is pretty sure it will get clawed back next year.

So, what does “saved it” mean? Saved it for next months rent? Saved it for expected childcare expenses? Saved it for future purchase of Tesla shares?

When the unknown danger of a pandemic is at hand, the real economy is shrinking around you, and you recognize $1200 doesn’t really carry very far, “saving it” has complex meaning.

I put half of mine into a foodbank as a donation, and then I went to Kult of Athena and got a dane axe, a wool tunic, viking boots, a seax, and some other odds and ends with the rest.

I already had the mail hauberk/round shield/9th century sword/spear, so I should be in pretty good shape for defense in the future once the rampaging mobs run out of bullets.

Just starting my motte and bailey now, but darnit….shaping stones is serious business, so i am going to have to stick with a wood palisade to start with. Anyone that wants to swear fealty to me can bring their peasants outfit, stone working tools, and/or farm animals to Hoodsport WA to claim their villein and join in the fun. (Preference given to experience with shield walls, blacksmithing, or grain/turnip farming)

Look for the 3rd motte & bailey on your left, just past the ruined villa. If you go past the Temple of Apollo you’ve gone too far. (don’t talk to the Vandals hanging around there…they are a bit unruly, but mostly harmless and will be gone once they make some boats & set sail for Carthage….)

Never got it.

I put all of it in the bank but then again I spent 3000.00 on friends and acquaintances in distress. One man I helped had no insulin. Still I’ve stashed away a fair sum.

Put it toward RE taxes. Money destroyed, job done.

A debt jubilee would have apparently cost 1/2 as much and achieved similar economic ends. A tiny fraction spent it and the rest stuck it in an hole in the ground.

Try getting our (UK) aristocracy to do anything economically productive!

They’ve been taking it easy for centuries.

So the stimulus worked as they wanted it to. It was used to save (which is invested in the market/Wall Street). Or it was used to pay down debt (debt owed to banks & other Wall Street debt holders). It protected Wall Street, which is all that mattered.