Lambert here: A turn-up for the books on open borders….

By Arun Advani, Assistant Professor, University of Warwick, Felix Koeni, Assistant Professor, Carnegie Mellon University, Lorenzo Pessina, PhD student in Economics, Columbia University, and Andy Summers, Associate Professor of Law, LSE. Originally published at VoxEU.

Top incomes have grown rapidly in recent decades and this growth has sparked a debate about rising inequality in Western societies. This column combines data from UK tax records with new information on migrant status to show that that migrants are highly represented at the top of the UK’s income distribution. Indeed, migration can account for the majority of top-income growth in the past two decades and can help explain why the UK has experienced an outsized increase in top incomes.

It is a well-documented fact that top-income growth has been particularly stark in English-speaking countries, with incomes of the top 1% and 0.1% rising sharply over recent decades (Atkinson et al. 2011, Blanchet et al. 2019). Some scholars have argued that the shared economic and political institutions of these countries, such as lower top marginal tax rates and light touch regulation, have incentivised rent-seeking behaviour among their top earners (Piketty et al. 2011, Bivens and Mishel 2013). In addition, technical changes may have created ‘winner-takes-all’ markets where a few workers earn most of the returns. Recent technological innovations may thus have contributed to the rise of top incomes (Rosen 1981, Kaplan and Rauh 2013, Koenig 2020).

Another characteristic feature of Anglo-Saxon countries is their popularity as a destination for high-skilled migrants, particularly the cities that serve as global services hubs such as London and New York (Kerr et al. 2016, Kerr and Kerr 2018, Roarch et al. 2019). Anecdotal evidence suggests that the rich and famous are internationally mobile and favour these destinations, but this evidence is based on a few highly visible cases. So far, we know little about the magnitude of these effects and the extent to which migration-induced selection effects could drive different trends in income inequality across countries and periods.

In a new paper (Advani et al. 2020), we combine top-income records from UK tax records with new information about migrant status to analyse the link. Tax records have been instrumental in recent research on top incomes. These data provide improved coverage of the highest incomes (reviewed in Atkinson et al. 2011); however, the data include minimal information on demographic characteristics. As a result, it has been difficult for researchers to distinguish native workers from migrant workers at the top of the income distribution, or to assess the impact of migration between countries on income dynamics. We derive information on migrant status from the structure of Social Security numbers assigned to migrant workers on arrival.

Our findings suggest that migrants are highly represented at the top of the income distribution. The public debate primarily focuses on low-income migrants; however, migrants make up a higher proportion of earners at the very top of the income distribution. Among low-income groups, about one in six people are immigrants. In contrast, among the top percentile of the income distribution, one in four people are immigrants and at higher fractiles, every third person is an immigrant. A lack of data has created a perception that migration is mainly a low-income phenomenon, but these new data show that the economy relies most heavily on immigrants for extremely highly paid positions.

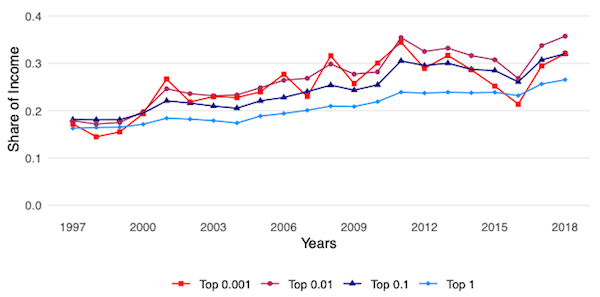

The inflow of high-income migrants can also help in understanding recent trends in top incomes. In the UK, an inflow of high-income finance workers can account for much of the observed rise in top-income shares over the past two decades. Immigrants make up more than a quarter of the top percentiles’ income share, up from 18% in 1997. Over these two decades, the importance of migrants thus increased by 50%, which accounts for about 85% of the rise in top income over this period (Figure 1a).

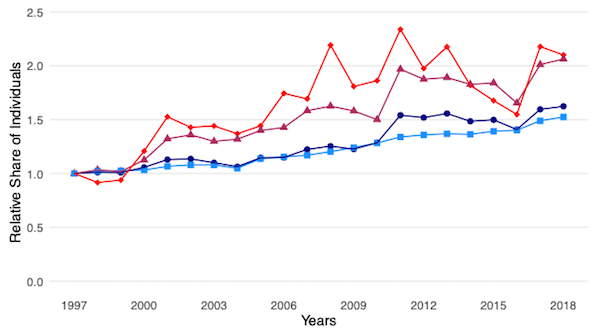

The impact of migration is even starker at higher income levels. Among the top 0.1% and 0.01% top, migrants make up roughly a third of UK top incomes (Figure 1a). This pattern aligns closely with the observed expansion of the wage distribution at the top. Incomes in the very top fractiles of the income distribution have grown the fastest in recent decades, pulling away even from the rapidly growing incomes in the lower end of the top 1%. The data suggest that differential migration rates can rationalise this ‘fractal inequality’. The inflow of migrants into the top 0.01% was nearly twice as large as the comparable inflow into the top 1% over the past two decades. Hence, differential migration rates may have increased the gap between the incomes of the top 1% and the top 0.1% (Figure 1b).

Figure 1a Percent of top incomes earned by migrants

Figure 1b Growth in number of migrants with very high incomes (1997=1)

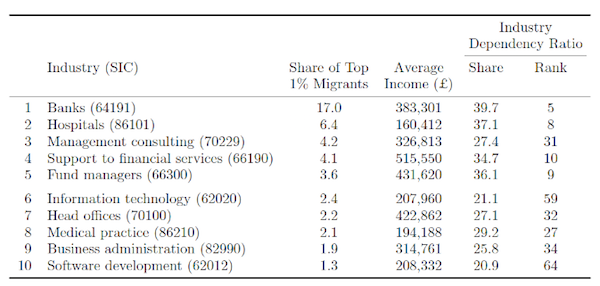

Looking at the main drivers of top earner migration, the results show that migration patterns are closely linked to the rise of finance. Banking, financial support services, and hedge funds together employ about a quarter of migrants in the top 1% (Table 1). The research evaluates which industries rely most on foreign talent and define the dependency ratio as the share of top paid individuals – with incomes among the top 1% of the UK income distribution – who are immigrants. A high-profile case is professional sports – among sports clubs, the dependency ratio is about 31%, meaning that three in ten top-paid workers are from abroad. In the three finance-related industries mentioned above, the dependency ranges from 35% to 40%, which is higher than in sports clubs and substantially above the 24% dependence in the average economy.

Table 1 What industries do top 1% migrants work in?

Note: This table presents statistics on migrants within 5-digit industries. “Share of top 1% migrants” is the fraction of all migrants in the top 1% who are in this industry. “Average Income” is the mean total income of top 1% migrants employed in this industry. “Industry Dependency Ratio: share” is the fraction of all top 1% workers in this industry who are migrants. “Industry Dependency Ratio: rank” is the ranking of the industry from highest to lowest fraction of all top 1% workers who are migrants.

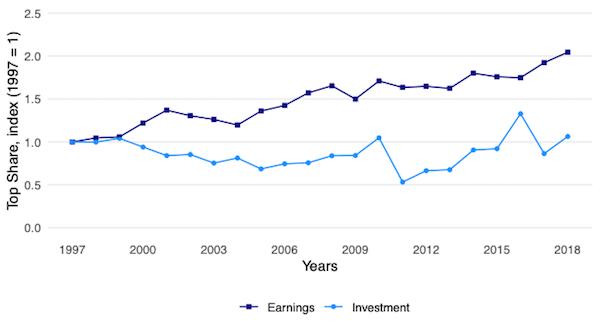

The migration of ‘global elites’ such as Lakshmi Mittal and Roman Abramovich to the UK has shaped a public perception that London is where the rich come to park their money. A natural question is: What role does this group of rentiers, who mainly receive investment income, play in driving the rise of top incomes? The results show that migration of rentiers had a small impact on the top UK income figures. Splitting top incomes into incomes from earnings and incomes from investments shows that investment incomes have remained nearly unchanged throughout the sample period and that earned incomes are the primary driver of the findings (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Trends in employment and investment income of top 1% income migrants (1997=1)

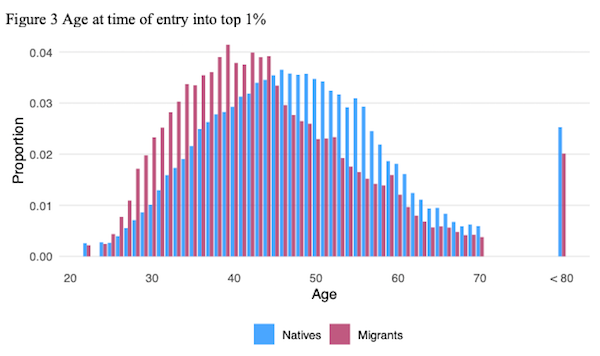

A prominent public policy concern is how easily similar native workers could replace migrant workers. While the research does not present direct causal evidence on the ease of substitution between natives and migrant workers, the results suggest that migrants are highly positively selected compared to the pool of similar natives. A first set of results shows that migrants reach top incomes at significantly younger ages than natives. The median age for natives who joined the 1% in 2017 was 47, and the distribution is roughly symmetric around that (Figure 3); the median age of migrants entering the 1% was 42, with the distribution skewed to the right. A second indicator is that migrants are increasingly represented at higher income levels. On average, a migrant in the top 1% has an 8% higher income than a native in the top 1%. Finally, the results show that firms poach highly paid, mid-career workers from abroad and place them straight into top paid positions. This poaching is far more common than cases of firms hiring UK trained foreigners who reach top paid ranks later in life. All of this points to an essential role for foreign specialist expertise in the UK economy.

Figure 3 Age at time of entry into top 1%

Most explanations of top incomes focus on income inequality among a fixed pool of workers, and in this framework, it has been difficult to quantitatively match the large top income shift observed in the data (Gabaix et al. 2016). By bringing migration into the picture, we highlight that the top 1% of people are not a fixed population, and that migration can amplify top-income growth. In the UK, migration can account for the majority of top-income growth in the past two decades and can help explain why the UK has experienced an outsized increase in top incomes.

Today’s Links article in the New York Times

Housekeepers Face a Disaster Generations in the Making,

Read the top comments.

The elite who dutifully subscribe to the NYT, all seem to have housekeepers, servants, staff, nannies, maids, housekeepers, cleaning ladies, daycare, gardeners, landscapers–whom they just adore!

All at reduced prices made possible by immigration, legal and illegal, while their poor fellow Americans hold out for the chimera of a livable wage job.

Prediction: The pandepression means that soon an American, Women’s, Ethnic Studies, art school, psychology graduate will be competing to clean the toilets of the elite and to leave witty and artful want lists and notes for their masters around the house.

Get those resumes polished gentle people.

If those graduates were smart, they’d hie themselves on over to their local community colleges and learn some trade skills. Y’know, carpentry, plumbing, electrical, HVAC. That sort of thing.

Such a sad lie we tell the young, go to college and you can be whatever you want! With the current climate collapse unfolding, I even wonder about trade school advice. Probably better to figure out how to grow crops on Canadian shield. That, or how to fire-proof crops.

Plumbers are getting $100 an hour hereabouts.

Problem is, soon people won’t be able to afford that.

There are always less expensive plumbers. Here’s an example:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OP30okjpCko

>carpentry, plumbing, electrical, HVAC

And what a dull world it would be.

Y’know, people used to get Humanities degrees and get by just fine.

… and then go be carpenters and plumbers after a stint in the food service industry…made for an interesting workforce back in the day.

Good luck with that. I’ve found it very easy to spend time and money in a technical school to get a trades education but very difficult to find anyone to hire you as an apprentice afterwards. All the time hearing about the demand for people in various trades but never seeing any apprenticeship job openings. The only exception I’ve seen to this personally was my next door neighbor who heard that CN Rail needed people. In that case they really did need people as shown by the fact that the company itself was willing to spend their own time and money training them. It’s involved a lot of hard work and time away from home but the job was actually there as opposed to the constant struggle to find employment in pipe fitting as an apprentice which was so sparse he was joking that he would probably die of old age before completing his apprenticeship.

Agreed. This week, while enduring the home remodel from Hell (yes, a first-world problem so I won’t carp), I’ve had a general builder/contractor, a plumber and an electrician in who I’ve either used before or hired on recommendation. They’ve done great work. One had an apprentice (the plumber) but all the others said it wasn’t viable in the current uncertain economic outlook.

Every single one of them had learned their trade in the military. When they’d reached an age (mid forties, usually, I think) where they could leave with some money, a reasonable pension provision already in place and (I’m guessing but I think it’s correct) grants from the forces demobilisation unit in the UK government to help set up a business plus some business support in the way of getting a business plan together, helping with the tax and accounting registrations etc. they set up as sole traders.

All said they could make a reasonable living but only as a second career (in other words, their children had grown up, they’d got on the housing ladder or even a rung or two up it already). And they’d not had to have not only some zero-income years while training in a formal education setting but also some savings for the business start-up costs (or, conversely, to take out loans).

The plumber’s apprentice reported precisely as detailed above by RMO: his cohort who had just left technical college but were desperate to get taken on to get real-world, hands-on experience (plus to start actually earning money). The few who’d managed it had had to leave home (not ideal, with little to fall back on) and move to where there were hirings. I asked the guy if he knew who was hiring — High Speed Rail 2 contractors in the midlands (here in the UK) and Hinckley Point C build-out (notionally a private construction project but in reality the UK government is propping up France’s EDF and using state-aid-in-all-but-name to cover the UK operator’s budget, which has moved into blank cheque territory).

A couple of others are thinking of joining the army (thereby perpetuating the whole cycle).

Nothing, then, by way of support from the real private sector. Who then complains of “skills shortages”.

Neither is “better” for the world. As John Gardner said, “The society which scorns excellence in plumbing because plumbing is a humble activity and tolerates shoddiness in philosophy because it is an exalted activity will have neither good plumbing nor good philosophy. Neither its pipes nor its theories will hold water.” At this stage of college-for-all, we do have many MBAs absent good sense who area acting as tradesmen. They do not think nor analyze. They just follow existing practice. Economics majors do not think; they just blindly follow models and make policy on such assumptions. In the trades, few are willing to learn from masters; they just blithely join pipes or wires without caring for the overall design. Where is systems thinking taught or learned? Systems thinking combined with a humanitarian outlook could stabilize the real world picture. Developing a public attitude of personally not doing that which would hurt society if everyone did it will go farther than mere change in the number of graduates of any trade school–and business school teaches a trade. Do not confuse four years of any college with acquiring a leadership/stewardship mindset. Do not confuse several years of trade school with acquiring a stewardship/leadership mindset. Pubic attitudes matter.

Better that than getting rekt daily at home. ;)

Er, this is so upside down it should be about Australia:

– the migrant age of 1%’ing is skewed left, not right, by inspection and by its description

– the rentier migrants do not affect the income statistics by definition, they are coming to take advantage of the non-dom rules and the great bulk of their true income is not remitted to the U.K. and therefore not counted by HMRC. Nevertheless it enables them to outbid domiciled taxpayers on assets and goods and services. Their Mayfair houses are owned by offshore trusts, their expenditure is funded by loans (there are loopholes in the capital matching rules that in theory clawback the advantage of untaxed gains / income rolled up offshore) or otherwise disguised, for example as capital gains or carried interest on their own investment portfolios, structured as investment companies selling substantial shareholdings (CGT exempt) and then contributing the capital into family partnerships (sidestepping the loan relationship / close company distribution rules).

– if there were no migrants for banks to hire, what then? They would hire locally at the same or higher salaries. It is the FIRE economy driving salaries and income inequality, the migrants are probably helping to keep them down with wage competition.

There are none so blind as will not see.

Keep in mind that the 1%ers are left on social issues, but economically quite right wing.

Percentage wise, you will not see that many people supporting Labour parties in either the UK (under Cobryn) nor the economic agenda of the more left wing elements of the Australian Labor Party.

One wonders how much the rich immigrants were a contributing factor to Brexit.

Although it does not reach as much attention, it seems like the real problem is that Finance has become a sort of rent seeking parasite, taking the economic gains for itself. Compensation in finance needs to be reduced across the board at the top levels.

Here’s a compelling quote.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/belief/2016/nov/17/diversity-can-distract-us-from-economic-inequality

The same could be said of the Tony Blair style “new Labour” politics, which is economically very neoliberal and socially very pro-immigration, pro-EU, and fiscally pro-austerity at times. They are a better fit than an economically conservative, but also socially conservative Tory party.

In a sense, Brexit has changed the equation. The UK is now far less appealing to high finance. The is will mean that many of these 1%ers will leave. The tragedy here is that the average working class British national will also face negative economic consequences and much more so than than the very rich.

My UK knowledge is not extensive (I know Grenfell!) but +1 as to the rest of your comment.

Brexit enjoys considerable support amongst “drawbridge migrants” — mainly second or third generation Indian or Pakistani descent. There a several (very) extended family groups which have build up, quietly, without much public display of wealth or fuss, vast and lucrative business empires in various fields (food processing, lodging, healthcare, law and tax accounting, to name few of the main ones). No fans of EU immigration they, but will undoubtedly look to influence UK immigration policy to better favour commonwealth countries in the future.

We (UK) bend over backwards to make the rich, richer.

Not quite as much as the US, but its pretty close.

Rich people flock here from other countries because the UK is a good place for rich people to be.

What can we specialise in for globalisation?

How about finance in the City?

We live in London and the money will flow out from the City into our pockets.

What about the rest of the country?

Who cares, we live in London

Anyone living in or near London did really well.

Lucky for me, that’s where I live.

The globalists found just the economics they were looking for.

The USP of neoclassical economics – It concentrates wealth.

Let’s use it for globalisation.

Mariner Eccles, FED chair 1934 – 48, observed what the capital accumulation of neoclassical economics did to the US economy in the 1920s.

“a giant suction pump had by 1929 to 1930 drawn into a few hands an increasing proportion of currently produced wealth. This served then as capital accumulations. But by taking purchasing power out of the hands of mass consumers, the savers denied themselves the kind of effective demand for their products which would justify reinvestment of the capital accumulation in new plants. In consequence as in a poker game where the chips were concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, the other fellows could stay in the game only by borrowing. When the credit ran out, the game stopped”

The problem:

Wealth concentrates until the system collapses.

Actually that isn’t a problem.

Wealth concentrates until the system collapses.

Those with all the wealth then pick up loads of distressed assets in fire sales.

It just gets better and better.

It works a treat.

It’s all been tried and tested.