Yves here. I thought the “return of the CARES Act Funds” by the Fed sounded utterly bizarre since the Fed already has authority under Section 13.3 of the Federal Reserve Act to lend to pretty much anything, including, as former central banker Willem Buiter put it, a dead dog. So I must confess to not paying much attention at the time to the inclusion of a provision in the CARES Act allotting up to $454 billion to the Fed to lend. The Fed didn’t need Congressional authorizations or support to do QE, so why now? And then why the bizarre ruse of Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin asking the Fed to return money it never had or needed, and Fed Chairman Jerome Powell agreeing?

Nathan Tankus correctly states this was an accounting gimmick and one with no apparent reason. Yes, Dodd Frank added a provision to Section 13.3. requiring that the “security” for any Fed lending be adequate to protect taxpayers from losses and establish a “lendable value” for those securities. So no dead dogs as collateral! But actually not really, since a central bank has no requirement to have a positive net worth. We’ll quote at length from this post on the Money & Banking blog:

If you ask monetary economists whether we should care if a central bank’s capital level falls below zero (even for an extended period of time), most will say no. Pose the same question to central bank governors, and the answer in nearly every case will be yes.

What accounts for this stark difference? How can something that seems not to matter in theory be so important in practice?

The economists correctly argue that central banks are fundamentally different from commercial banks, so they can go about their business even if they have negative net worth. However, central bankers know instinctively that the effectiveness of policy depends critically on their credibility. They worry that a shortfall of capital would threaten their independence, which is the foundation of that credibility.

Yves here. I don’t want to make this long post overly long, so I will skip over a proper kneecapping. The thumbnail version is central bankers don’t want to have to ‘splain themselves since it would undermine their Wizard of Oz mystique. Recall that Greenspan made a point of being incomprehensible.

Back to the Money & Banking post:

Let’s start with the economists’ perspective: there are several reasons to believe that central banks should have no difficulty operating with negative capital. First, a central bank can issue liabilities regardless of its net worth. It can never be illiquid. Second, because it is really part of the government, it is reasonable to consolidate the central bank’s balance sheet with the government’s broader balance sheet. From this standpoint, it is of little import whether a single part of the larger balance sheet exhibits positive or negative net worth. Instead, when thinking about the government as a whole, we ask whether it has access to sufficient revenue to meet its obligations, both debt repayment and otherwise.

Third, and most important, in a world of stable prices, under almost any reasonable set of assumptions, the central bank’s future profits will be more than sufficient to offset a moderate capital shortfall in a reasonable time frame. Why? Central banks earn seignorage – the real value of the goods and services that they can command through the creation of central bank money (currency and reserves). That is a big reason temporary episodes of negative cash flow do not pose a policy challenge. [Keep in mind that central banks do not operate for profit, but rather to secure a public purpose (such as economic stabilization), and that (with only a few exceptions like the SNB) they do not issue stock that trades in financial markets or can be used as collateral.]

While seignorage is finite, it is very large even in low-inflation countries.

We then get to the question, why are Mnuchin and Powell engaged in this headfake? Seems to me the point is to further embarrass Pelosi, who turned down Trump’s offer of a $1.8 billion stimulus deal, by pretending that there’s money left over from the CARES Act and why isn’t Congress making use of that?

Please remember we are starting our comments holiday. Comments for this post have been turned off.

By Nathan Tankus. Originally published at Notes on the Crises

My most loyal readers may recall my piece on the 454 billion dollar CARES act appropriation for the Federal Reserve: “A Quarter of the 2 Trillion Dollar “Stimulus” Bill is Devoted to a Useless Accounting Gimmick“.

That piece was published before the CARES Act was even law. At the time, my main concern was that this appropriation inflated the dollar amount of the legislation. This made it appear that there was more income support being provided to households, state & local governments, and businesses than was actually forthcoming. The CARES Act also seemed to obscure how relations between the Federal Reserve and the Treasury worked — therefore also causing confusion over how money works in the United States.

As public debate continued, I became focused on the problem of arbitrary quantity limitations. My concern was that adhering to these useless “accounting gimmicks” could potentially arbitrarily limit Federal Reserve programs, though this ultimately didn’t come to matter as the so-called announcement effect of these programs ended up being sufficient. I haven’t returned to this topic in a long time, because its urgency receded. So at this point, the details have likely receded from my readers’ memories.

Now however, it’s been announced that secretary Mnuchin is “asking for the CARES act money back”. This has been widely reported as a “clawback”. So at this point, it’s worth explaining the games and gimmicks from first principles, to see what “giving the money back” could even mean.

This story all begins with a CARES Act provision that states:

Not more than the sum of $454,000,000,000 and any amounts available under paragraphs (1), (2), and (3) that are not used as provided under those paragraphs shall be available to make loans and loan guarantees to, and other investments in, programs or facilities established by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System for the purpose of providing liquidity to the financial system that supports lending to eligible businesses, States, or municipalities.

So this is 454 Billion dollars that can be ‘invested in’ “programs or facilities” that the Federal Reserve sets up. But why the hell do the people that create money need “investments”?

There are all sorts of … questionable reasons motivated by academic economics one may point to. But the most generous interpretation is a provision of the Federal Reserve’s emergency authority found in section 13.3 of the Federal Reserve Act. (This was originally inserted by the post-financial crisis reform of 2010 Dodd-Frank.) I’m going to quote the paragraph in full because it’s relevant, but there is one specific part that matters most:

As soon as is practicable after the date of enactment of this subparagraph, the Board shall establish, by regulation, in consultation with the Secretary of the Treasury, the policies and procedures governing emergency lending under this paragraph. Such policies and procedures shall be designed to ensure that any emergency lending program or facility is for the purpose of providing liquidity to the financial system, and not to aid a failing financial company, and that the security for emergency loans is sufficient to protect taxpayers from losses and that any such program is terminated in a timely and orderly fashion. The policies and procedures established by the Board shall require that a Federal reserve bank assign, consistent with sound risk management practices and to ensure protection for the taxpayer, a lendable value to all collateral for a loan executed by a Federal reserve bank under this paragraph in determining whether the loan is secured satisfactorily for purposes of this paragraph.

Thus the Federal Reserve, Trump’s Treasury department and members of congress sought an appropriation of “funds” specifically for the Federal Reserve in order to satisfy that provision. So they included a formulation promising “taxpayers” would be protected from loss because … the treasury will take the loss.

I have for a long time found this interpretation overly narrow. The statute does not define “taxpayers”, “sufficient” or “security”, and clearly leaves it to the Federal Reserve’s judgment what is “sufficient security” for its emergency lending programs. There are multiple interpretations of all three of these terms, some of which would make this accounting gimmick unnecessary. I will return to this point later on. For now, it’s important to fix our minds on how exactly this accounting gimmick has played out in practice.

A naïve reader of the paragraph of the CARES act devoted to “investments” in the Federal Reserve may come away with the impression that the treasury had to go “out there”, to find willing private buyers of its treasury securities in order to make these “investments”. This, it turns out is not the case.

As professor Scott Fullwiler and his colleagues pointed out, no treasury funds were transferred to the accounts of the special purpose vehicles the Federal Reserve chartered. (“Treasury funds” here used in the sense of a balance on the Federal Reserve checking account — AKA the “Treasury General Account”.)

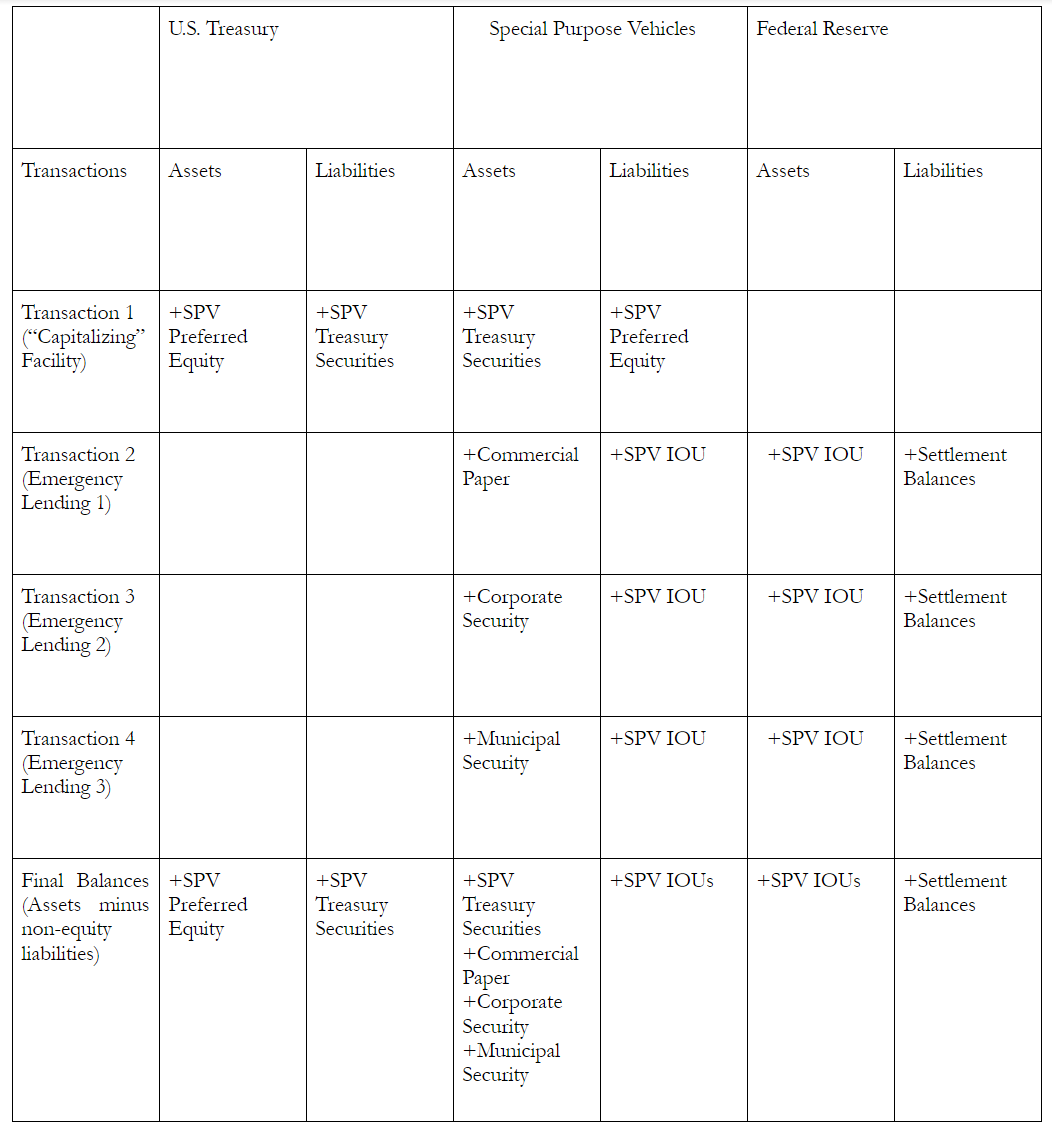

Instead, the Treasury simply created and placed “non-marketable” treasury securities they labeled “SPV securities” into the accounts of these special purpose vehicles. (These securities were “non-marketable” in that they were restricted from sale to third parties.) The SPVs, in turn, provided the Treasury with preferred equity shares for their deposit of “SPV securities”. They didn’t “use these funds” to make loans. Instead, once the SPV was capitalized, the Federal Reserve simply started purchasing assets and lending under 13.3.They booked the assets as owned by the special purpose vehicles, along with a corresponding liability owed to a federal reserve bank. You can see this represented below:

(For details on how equity liabilities are treated in a T account framework, see my #MonetaryPolicy101 introduction here). As long as the assets acquired (and the cumulative returns on those assets) didn’t fall below the special purpose vehicles “liabilities” to the Federal Reserve, it would undertake no losses. Notice that in this framework, all the “SPV security” is doing is being an arbitrary asset, with monetary value. It’s not saleable, while technically it can be presented for “redemption”. So why would the Federal Reserve want to use redemption to arbitrarily debit the Treasury’s checking account?

To repeat the obvious point: the Federal Reserve can simply create more settlement balances elsewhere in order to make payments.

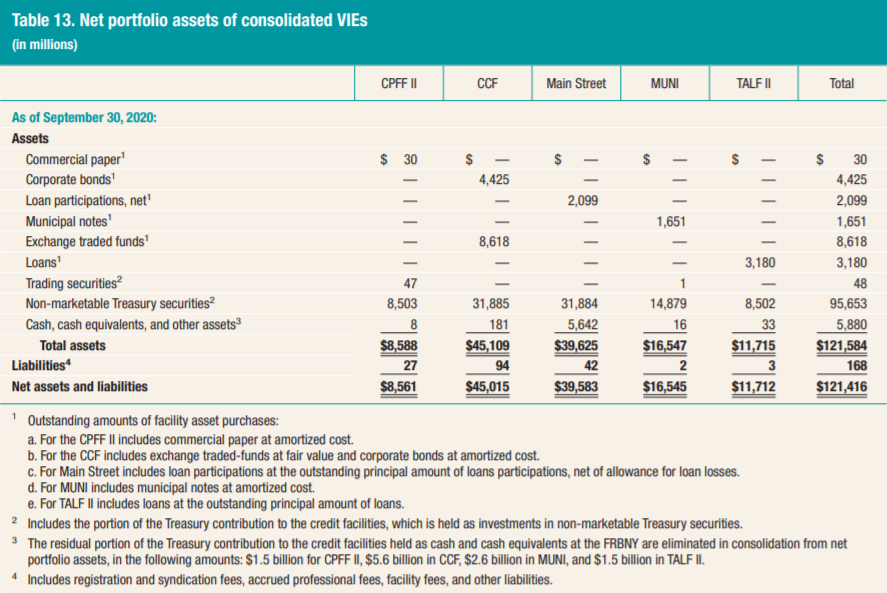

So, for example, the Trillion Dollar Platinum coin could easily take its place with no operational differences. You can see the actual numbers in the Federal Reserve’s own quarterly financial statements.

In sum, the “capitalization” of Federal Reserve facilities has indeed been a big “accounting gimmick”. And one which has obscured how the Federal Reserve’s crisis response works. That would be bad enough, but now the confusion this mess has created has given Treasury Secretary Mnuchin an opening for a cynical maneuver. It looks like this:The Federal Reserve’s facilities have not been very utilized — whether because of unfavorable pricing and maturity offerings, lack of interest in going deeper into debt, or their very existence making borrowing from them unnecessary. So Mnuchin has now asked the Federal Reserve to “return the unused funds”. Bafflingly, Federal Reserve chairman Powell agreed.

Yet, it has not been clear in the Federal Reserve’s public statements what this means. And, as COVID-19 Congressional Oversight Commission member Bharat Ramamurti points out, the contracts which established these emergency facilities have specific processes for being liquidated. And these don’t allow for “interim distributions”. It would be a far bigger deal if Mnuchin were trying to liquidate facilities. That would necessitate selling the acquired assets, and not simply decreasing or stopping lending.

To elaborate, here are relevant portions of the Treasury-Fed contract on the state/local program.

“Preferred Equity Member” (Treasury) commits $35B to “Managing Member” (Fed). Can’t change that without agreement of the Managing Member.

Other contracts have similar language. https://t.co/GA2BnwwMem pic.twitter.com/c6sKb6478x

— Bharat Ramamurti (@BharatRamamurti) November 19, 2020

Let’s step back for a moment. Why does Mnuchin want the funds returned? His stated reason is he wants the funds “reappropriated” and spent by congress. But, as we’ve seen, all these “funds” are nonmarketable treasury securities! They are not saleable.Even if they were, the treasury can issue a treasury security right now.

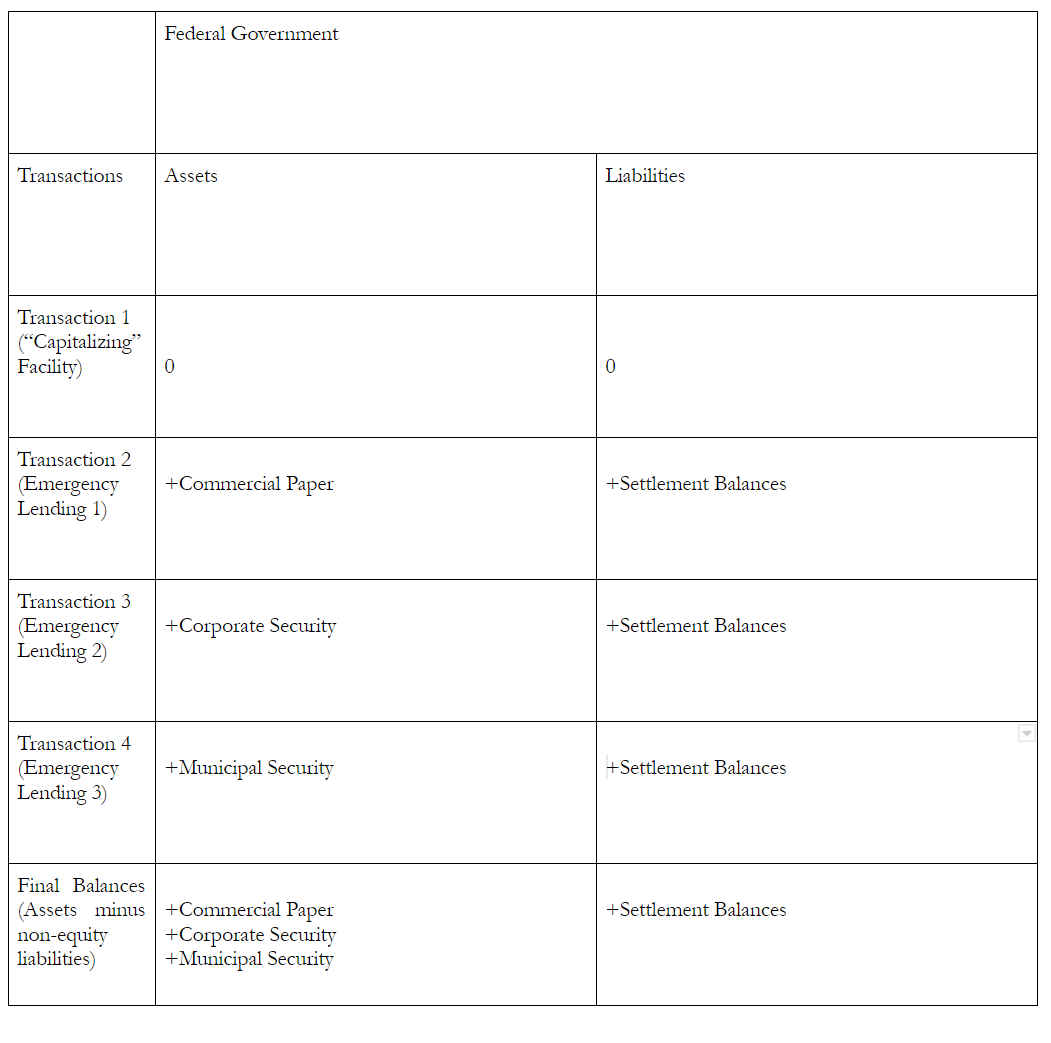

If a SPV security sits dormant on the balance sheet of an emergency crisis facility, does it make a sound? Even more fundamentally, this is all intragovernmental accounting! When you consolidate the Federal Government together, these intragovernmental accounts disappear. As I explored at the end of June, when you consolidate the entire Federal Government together you find that federal government lending and spending is always “money financed”.

There is no money to be “reused”. It’s not a “payfor” to have these nonmarketable securities transferred from one part of the Federal Government to another. Another way you can tell this is the Congressional Budget Office “scored” these “funds” as having no “net effect” on the deficit. This was simply because the emergency facilities are presumed to not take losses greater than their net income. Spending on support to state and local governments and expanded unemployment benefits would not get such a score. This is all blatant nonsense, which means it may be possible to convince republican senators playing such boring games of three card monty.Others who watch this space closely are alarmed by these developments. I’ll admit that I am feeling something more like annoyed bemusement. Accounting gimmicks this silly are bound to chase their own tails in this way. The CARES act could have avoided this whole issue by creating statutory authorization for Federal Reserve lending during Coronavirus that was not contingent on some “pot of money” out there. As I argued in May, the CARES act could have simply booked all losses related to 13.3 emergency programs to a “Money-Financed Authorized Crisis Response Account” (MACRA). That approach would have little difference to “SPV securities”. Even now, many options still remain. Mnuchin’s own letter requesting the funds returned states that: “In the unlikely event that it comes necessary in the future to reestablish any of these facilities, the Federal Reserve can request approval from the Secretary of the Treasury and, upon approval, the facilities can be funded with Core ESF funds”.Since these facilities don’t require capitalization by the treasury at all, they certainly don’t require a certain level of capitalization to function. Whether SPV securities are 10% of a facility’s assets or 70%, the Federal Reserve can create settlement balances through lending or purchases, and acquire assets. Even more fundamentally, none of the key terms in the key part of the Federal Reserve act governing emergency lending are defined. If the Federal Reserve engaged in emergency lending and purchases and declared that those assets were “adequate security” to “protect taxpayers from loss”, what specific statutory language would contradict them?Even if you don’t believe the Federal Reserve could justify acquiring just any asset this way, it certainly could make the case that “taxpayers” are protected — provided the Federal Reserve’s net income could absorb loss levels judged to be “improbable”.

These terms are just so vague it’s hard to see how very many interpretations could be definitely excluded. Further, who would have standing to sue the Federal Reserve over this? Hell, the Federal Reserve could even declare that “taxpayers” were protected — since emergency lending isn’t connected to any discretionary tax increases or spending cuts.

Yet, to admit any one of these options are viable would be to give the game away. It would also mean that all of the convoluted back and forth over the capitalization provisions in the CARES act were a complete waste of time. The Federal Reserve’s general counsel could be a bottleneck in this respect, though it’s unclear whether he’s been backing the dominant interpretation where capitalization of emergency facilities is absolutely required.

Certainly, if Powell and the Federal Reserve is buckling under pressure from a lameduck administration over something that clearly goes against previous contracts and congressional intent, legal counsel may come up with more “flexible” definitions of otherwise undefined terms.

Hopefully, Janet Yellen will be willing to cut through this Gordian knot. At one level, this is all much ado about nothing. At another level, the layers of accounting gimmicks and obfuscation are a deep problem which alienates the public from policymaking and makes it impenetrable. Why should funding vital relief for the public require this many twists and turns just to get cash out the door?