America’s cultural bias towards optimism leads to a predisposition to underplay unpleasant episodes, and that includes our Thanksgiving holiday. We’re less than 20 years past the War in Iraq, and W’s war crimes seem to have been airbrushed out of the collective memory. In Europe, Good Friday, the culmination of Christ’s suffering, is the most strictly observed day of the Holy Week. In Australia, the only two days pubs are closed are Christmas and Good Friday. But in the US, it’s cheery Easter, including the non-religious elements like Easter egg hunts, that takes the fore.

Thanksgiving has become a turkey and football-themed bacchanal, and there’s nothing wrong with a harvest feast as an excuse for seeing family and friends (at least in non-Covid times). But the usual short accounts of Thanksgiving’s origin conveniently airbrush out how extreme the suffering was before the harvest feast of fall 1621.

Most people do dimly recall that the Separatist Puritans, later the Pilgrims, were religious extremists who fled from England and tried establishing a community in Leiden, only to find that they didn’t like the immigrant lifestyle: some could find only servile jobs and they feared becoming assimilated. The congregation was shrinking as older members who’d run out of funds and younger people who were having difficulty getting enough work returned to England but younger people weren’t emigrating to replace these losses.

To make a long story short, after casting about and a lot of machinations, the Pilgrims secured a land grand from the London Company for a settlement on the Hudson River, with the proviso that their religion would not receive official recognition from the crown. Only a portion of the congregation could go, and the leaders decided it should be the youngest and fittest.

The plan was to charter two ships: the smaller Speedwell, which would stay in North America for fishing, and the larger Mayflower. The Speedwell went from Leiden to England but developed leaks; later accounts found the crew sabotaged the ship because they didn’t want to go to America. 120 passengers had been originally set to sail; that was cut to 102 due to the loss of the Speedwell. Only about 1/3 were Puritans; the rest were recruits of London Merchant Adventurers and servants of the Puritans and the other passengers. The crew totaled roughly 30.

One has to wonder who would sign up with a bunch of religious crazies to cross the ocean and try to set up a colony when others had failed. Were they desperate to get out of Dodge? Or did London Merchant Adventurers misrepresent the “opportunity”?1

The part that is too often glossed about Thanksgiving is how horrific the first winter was. The Mayflower got off late due to all the trouble with the Speedwell. The voyage over was miserable and much longer than expected due to storms; at one point, the ship was so severely damaged that the crew thought they needed to return to England, but a passenger remarkably had an oddball piece of equipment that enabled them to repair the mast. Two passengers died en route.

The Mayflower had been blown north and set anchor close to the current Provincetown on November 11. They spent more time trying to find the location for a settlement; a skirmish with some Native Americans during their expeditions (and looting of burial grounds) led them to shift their focus. They chose a spot called Plymouth by John Smith during his surveys, which had been cleared by Native Americans but abandoned. They anchored on December 21 and sent the first construction crew ashore on December 25. They managed to make progress on the common house, where some lived during the winter; others stayed on the ship. The crew had intended to return to England straight away but it was too late in the year to do so.

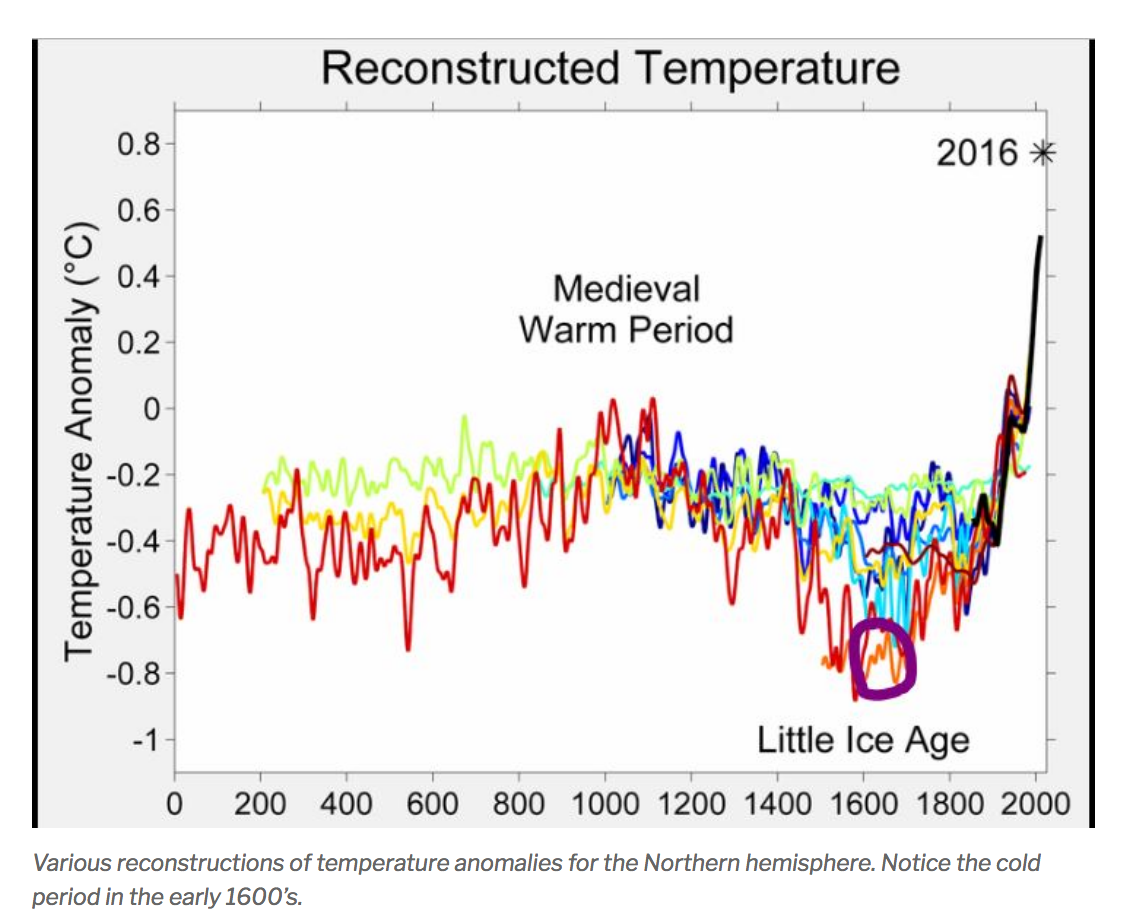

Mind you, 1620 was close to the nadir of the Little Ice Age. From Weather Concierge:

But even with that winter being the milder than any other in the following decade, nearly half of the passengers and crew died of exposure, malnutrition, particularly scurvy, and disease, such as pneumonia and tuberculosis. Most were originally buried in unmarked graves; some of the bodies were later moved to a mass grave called The Tomb.

The Pilgrims preference for hardiest was limited to their fellow congregationists. The list of the servants to the Puritans is not pretty. From Wikipedia. Asterisks denote fatalities during the first winter:

Butten, William* (possibly Nottingham), “a youth”, indentured servant of Samuel Fuller, died during the voyage. He was the first passenger to die on November 16, three days before Cape Cod was sighted.

____, Dorothy, teenager, maidservant of John Carver.

Hooke, John*, (probably Norwich, Norfolk) age 13, apprenticed to Isaac Allerton, died during the first winter.

Howland, John, (Fenstanton, Huntingdonshire), about 21, manservant and executive assistant for Governor John Carver.[23]

Latham, William, (possibly Lancashire), age 11, servant and apprentice to the John Carver family.

Minter, Desire, (Norwich, Norfolk), a servant of John Carver whose parents died in Leiden.

More, Ellen (Elinor)*, (Shipton, Shropshire), age 8, assigned as a servant of Edward Winslow. She died from illness sometime in November 1620 soon after the arrival of Mayflower in Cape Cod harbor and likely was buried ashore there in an unmarked grave.

More, Jasper*, (Shipton, Shropshire), age 7, indentured to John Carver. He died from illness on board Mayflower on December 6, 1620 and likely was buried ashore on Cape Cod in an unmarked grave.[28]

More, Richard, (Shipton, Shropshire), age 6, indentured to William Brewster. He is buried in the Charter Street Burial Ground in Salem, Massachusetts. He is the only Mayflower passenger to have his gravestone still where it was originally placed sometime in the mid-1690s. Also buried nearby in the same cemetery were his wives Christian Hunter More and Jane (Crumpton) More.

More, Mary*, (Shipton, Shropshire), age 4[citation needed], assigned as a servant of William Brewster. She died sometime in the winter of 1620/1621. She and her sister Ellen are recognized on the Pilgrim Memorial Tomb in Plymouth.

Soule, George, (possibly Bedfordshire), 21–25, servant or employee of Edward Winslow.

Story, Elias*, age under 21, in the care of Edward Winslow.

Wilder, Roger*, age under 21, servant in the John Carver family.

Servants aged 4 to 11, including indentured servants aged 6 and 7? Wikipedia explains:

Other passengers were hired hands, servants, or farmers recruited by London merchants, all originally destined for the Colony of Virginia. Four of this latter group of passengers were small children given into the care of Mayflower pilgrims as indentured servants. The Virginia Company began the transportation of children in 1618. Until relatively recently, the children were thought to be orphans, foundlings, or involuntary child labor. At that time, children were routinely rounded up from the streets of London or taken from poor families receiving church relief to be used as laborers in the colonies. Any legal objections to the involuntary transportation of the children were overridden by the Privy Council. For instance it has been proven that the four More children were sent to America because they were deemed illegitimate. Three of the four More children died in the first winter in the New World, but Richard lived to be approximately 81, dying in Salem, probably in 1695 or 1696.

The Pilgrims looked down on their fellow voyagers, designating their members as “Saints” and everyone else “Sinners”. For what it is worth, none of the servants of the non-Puritan passengers appear to be younger than teenagers.

In short, this was a reckless, badly-planned venture. The Mayflower left England in September even though its original departure date had been the spring. This was as unwise a call as Napoleon’s march on Moscow. The only reason it didn’t have as bad a death rate was that the colonists got a lucky break on the winter, with the severe cold ending early, after February. As histories recount in some detail, the settlers got another big break by the Native Americans leaving them alone when the settlers were most vulnerable, in the depth of winter, and then having the first contact made by an Abenaki, Samoset, who spoke English he had learned from trappers and fishermen in Maine, and then Squanto, who was eventually very helpful despite having been abducted by an English explorer. Squanto had spent five years in Europe, initially as as a slave for a group of Spanish monks, returning as a guide and freed when the Massaquoit slaughtered the crew on his ship.

The fact that any of the passengers of the Mayflower made it through that winter proves Otto von Bismark’s jibe: “God loves drunks, fools, and the United States of America.” And I’m not giving the Plymouth colonists America points, since there was no United States then. They drank prodigious amounts on the trip over (beer being seen as safer than water) and no doubt returned to those habits as soon as they could. So being in a substance-created haze may be the real foundation of American optimism.

Please remember we are starting our comments holiday. Comments for this post have been turned off.

____

1 I am allowed to disparage them because they are in my gene pool. Depending on which genealogy you believe (the one fully backed by church records and gravestones, or the one for one branch by the Mormons where the records peter out), at least seven and as many as eleven of my ancestors came over on the Mayflower, none of them Pilgrims.