I’m a bit late to write up a solid article in the Financial Times: China pulls back from the world: rethinking Xi’s ‘project of the century.’ It discusses how China has substantially dialed down its once much-trumpeted Belt and Road initiative, in which it planned to fund massive infrastructure projects, largely along the former Silk Road, so as to provide land routes for exports and imports. It looked to be a geopolitical masterstroke, simultaneously reducing China’s exposure to having the US mess with China’s trade in the China Sea and other naval choke points; creating a co-dependency sphere (similar to what the US has with NATO) via directly funding important development projects in emerging economies.1

So what happened? The article keys off a recent report by Boston University’s Global Policy Development Center, titled Scope and Findings: China’s Overseas Development Finance Database. It has gotten some criticism (more on that shortly), but the Financial Times got confirmation of the thesis from multiple sources as well as other corroborating data points. So it’s reasonable to treat the Boston University account as directionally correct even though it arguably missed other funding channels that render its account less stark.

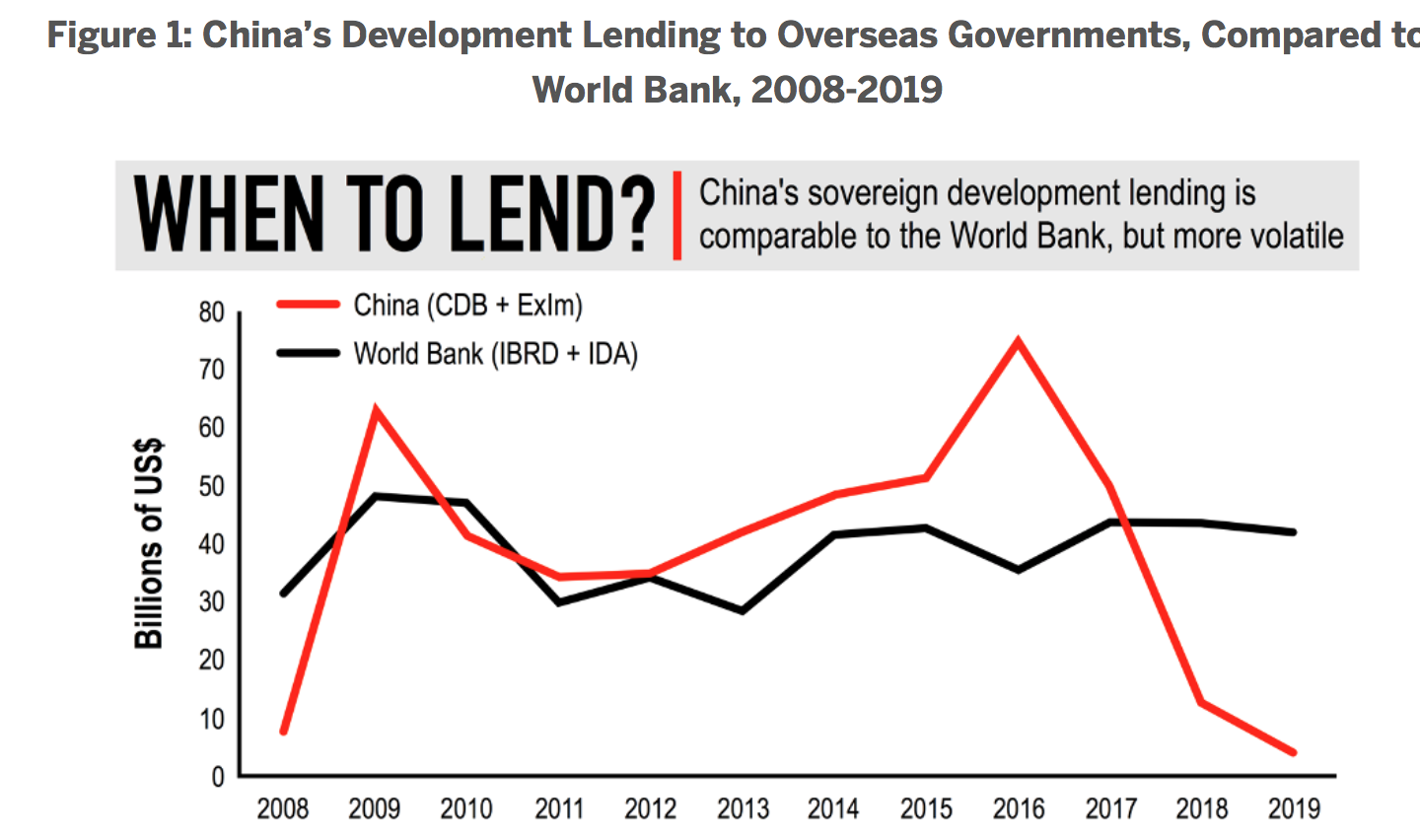

The high level recap of the Boston University report flags two major findings. The first is that China’s official development lending has fallen off sharply in recent years:

China’s lending also appears to be significantly about securing access to resources, as opposed to simply securing routes to them. Even though some readers have mentioned that China has been very active in Africa, I suspect many would assume it was private interests buying or negotiating deals with mineral and agricultural interests. The markers in Africa shows many official projects:

The Financial Times provides hard and soft data consistent with this picture:

In global development finance, such a sharp scaling back of lending by the Chinese banks amounts to an earthquake. If it persists, it will exacerbate an infrastructure funding gap that in Asia alone already amounts to $907bn a year, according to Asian Development Bank estimates. In Africa and Latin America — where Chinese credit has also formed a big part of infrastructure financing — the gap between what is required and what is available is also expected to yawn wider.

China’s retreat from overseas development finance derives from structural policy shifts, according to Chinese analysts. “China is consolidating, absorbing and digesting the investments made in the past,” says Wang Huiyao, an adviser to China’s state council and president of the Center for China and Globalisation, a think-tank.

Chen Zhiwu, a professor of finance at Hong Kong university, says the retrenchment in Chinese banks’ overseas lending is part of a bigger picture of China cutting back on outbound investments and focusing more resources domestically. It is also a response to tensions between the US and China during the presidency of Donald Trump, when Washington used criticisms of the Belt and Road as a justification to contain China, Prof Chen adds.

“In domestic Chinese media, the frequency of the [Belt and Road] topic occurring has come down a lot in the last few years, partly to downplay China’s overseas expansion ambitions,” says Prof Chen, who is also director of the Asia Global Institute think-tank. “I expect this retrenchment to continue.

Yu Jie, senior research fellow on China at Chatham House, a UK think-tank, says Beijing’s recently-adopted “dual circulation” policy represents a step change for China’s relationship with the outside world. The policy, which was first mentioned at a meeting of the politburo in May, places greater emphasis on China’s domestic market — or internal circulation — and less on commerce with the outside world.

Keep in mind that even though Trump has engaged in a lot of high profile China eye-poking, including his notorious tariffs, Biden is appointing China hawks to key positions, so the reduction in noise levels should not be mistaken for a willingness to accommodate. Recall also that the ultimate challenge for China is to manage the shift from being investment and export led to consumption-led. China has largely managed to postpone this transition.

As mentioned, not all China-watchers fully embrace this picture. The Diplomat contends that the Boston University data is flawed and China is continuing to lend, but more through state-owned enterprises. However, the author says he has an unpublished dataset (erm, show your work!) and cites examples only out of Eurasia, when as you can see from the map above, Africa and Latin America have also been major recipients.

I also wonder how much of this SOE lending is what Josh Rosner called, “A rolling loan gathers no loss,” as in extensions of what look like new credit to preserve the fiction that some sick projects are performing. From the Diplomat:

China’s policy lending in Eurasian Belt and Road economies is facing a raft of debt relief requests and a slowdown in bilateral government-to-government loans. However data analytics that focus solely on policy bank lending through bilateral agreements miss the wider geoeconomic picture. China’s policy banking environment in Central Asia is shifting, but the loan books of the future will be more heavily weighted to Chinese enterprises operating in host economies and host economy state-owned enterprises (SOEs)….

The Boston University interactive based on the dataset took a geospatial approach in examining China’s overseas development financing, focusing on biodiversity and indigenous lands. Loans not attached to a specific project with a geographic location were omitted from the original public data. This means ignoring multimillion dollar loans issued for non-greenfield investments, such as China’s 2010 $10 billion loan to the Kazakhstan sovereign wealth fund, Samruk-Kazyna, and a similar but smaller “no strings attached” loan to the National Bank of Uzbekistan.

As an aside, I don’t see why authors By Tristan Kenderdine and Niva Yau assume a loan to a sovereign wealth fund would have anything to do with development or even domestic investment. Most SWFs invest heavily outside their countries. Back to the article:

More importantly, some media analyses based only on the Boston University dataset, which only covers sovereign loans by policy banks, fail to examine how Chinese policy and commercial banks are behaving operationally in their foreign lending activities. China Development Bank, Bank of China, ICBC, and CITIC have all opened branches or subsidiaries in Kazakhstan, issuing a variety of loans to Kazakh businesses outside of the government-to-government loan scheme. These China bank operations are directly tied to China’s domestic banking superstructure and thus operate in an ambiguous space between state and market.

Again, I think it’s quite a stretch to conflate commercial lending with official development schemes. The Diplomat can argue that some of these loans outside the major development lender channels should be classified as part of the Belt and Road Initiative, but its eagerness to undercut the Boston University’s release looks to have led them to throw too many things at the wall and argue they all stick. Nevertheless, they do have a point with these illustrations:

Examples of China policy bank loans in Kazakhstan omitted from the Boston University database include China Development Bank’s $278 million loan to Kazakhstan for the construction of the Moynak hydropower station and a $1.5 billion loan to Kazakhmys to develop a copper mine in Aktogay, as well as the $500 million loan to Kazakh Development Bank to modernize the Shymkent refinery. Export-Import Bank of China has loaned $808 million to the Kazakh National Highway company for two highways, and another $300 million to Kazakh Finance Ministry for border modernization. These are all examples of policy bank loans with geospatial footprints.

A Financial Times reader provided a good overview:

HughCameron

OBOR (Belt and Road) looked like a wonderful way to keep China’s oversized state-owned infrastructure companies occupied as the 2008-2012 domestic construction boom wound down, and a great way to recycle the money from its trade surplus.

But China’s authoritarian leaders had a mistaken notion about the competence of the authoritarian partner governments they invested in. I saw this up close in East Africa. Projects took longer and cost more than planned, then produced low returns also because the client economies are typically managed for political stasis, not economic growth. China has faced the unwelcome choice between taking ownership of white elephants (Sri Lanka), or taking a haircut on the loans (almost everywhere else).

In the meantime, Xi’s domestic policy of favouring pliable SOEs led the CCP to wink at local government borrowing and to an overdue but necessary credit crunch. Simultaneously the ultracompetitive and financially independent Chinese private sector had to be knocked back before it became too powerful to regulate.

So Xi turned off the money tap to OBOR and messily cancelled Ant Group’s IPO because his need to maintain domestic financial (read political) stability is absolute.

While this is a setback for Xi Jinping, any third-world countries that replace their corrupt leaders will remain just as much in China’s pocket, and will have to continue extracting cash from their own longsuffering citizens.

So China will take the haircut on OBOR and suffer several years of below-potential domestic growth plus a delayed transition to a diversified consumer economy. It’s not as if Europe and America will do much better. Everybody makes mistakes

It’s no news that it’s hard to get a good reading on China from foreign sources. However, lending to developing economies is fraught, and it’s not surprising that China has had a lot of misses. Look at the Western sovereign lending train wreck in the 1970s that led to the Latin American debt crisis of the early 1980s. So keep an eye on what China does next.

_____

1 The Belt and Road Project has been incorrectly analogized to the Marshall Plan. Contrary to US myth-making, the Marshall Plan was not munificent. It was effectively recycling European flight capital back to Europe.

Going back at least 2 years now, I’ve seen reports that China’s banks have been very badly burned by the Belt and Road initiative. Quite simply, they are learning the lesson that Western and Japanese banks learned a couple of decades ago, that lending money to structurally weak economies is easy, getting your payments back is quite another matter. While the State owned sector in China is much more opaque, its hard not guess that they’ve found the going equally tough. While China has a huge surplus to get rid of and a massive infrastructure industry that needs a constant funnel of cash, there must be deep worries at the declining rate of return both domestically and abroad. Investing abroad for China looked I think a little like Private Equity did for the pension industry – a hail Mary throw to make up for declining returns from traditional sources. I suspect that it will be seen equally as a very poor decision.

You can see this at work with many of the major railway investments, in particular in SE Asia. The reality is that most railways have never made a direct economic return, even back in the mid 19th Century when investment was at its peak. Even less so when that railway has to go a long way through very difficult terrain. When I saw that they were going ahead with railways through countries like Laos it was very obvious that this was being pushed by political considerations and that long term economic losses would be gigantic. In a high growth economy, this can be sustained for a certain amount of time, but in the end, some sort of return is needed, and China is running out of options for this.

Incidentally, I’d wondered for some time why China is investing billions in aircraft carriers, while simultaneously investing in ballistic missiles that make aircraft carriers redundant. The only explanation I can think of is that aircraft carriers may be useful for parking off the shoreline of African nations who are not coughing up on their loan repayments. So maybe they’ve already considered this.

At the moment China is in a bit of a bind over the steady rise of the Yuan. They have a choice to let this happen, which will seriously constrain the export industry (and would also reduce the value of foreign investments), but would help raise the living standards of hundreds of millions of ordinary Chinese. So far, it seems like the hundreds of millions can wait, as it seems likely that they will keep trying to reduce its rise. Although paradoxically, one way of doing this is relaxing on capital controls to allow more private Chinese investors to put their money abroad. Some of it will be in railways, but I suspect most will be in San Francisco apartments.

Xi has only one real option to address the different issues – make a fundamental turn in the economy to favour ordinary Chinese people and encourage domestic consumption over infrastructure and saving. But it may be that structural issues have already made this impossible.

China doesn’t solely calculate direct returns to an industry, but takes the overall economic, social and political impact into consideration.

Infrastructure is in effect their “national loss leader” and other sectors are expected to make up for the losses. By bringing countries into their sphere of influence they save on military resources, increase their market share, and can offset their demographic decline with access to younger labor pools (hiring their competition) . In a neomercantilist world, the cost of logistics is outweighed by victory.

Unfortunately, Americans are shortsighted stingy bean counters which was bred into them by their obsession with stock market and the dopamine hit they get from market volatility. China is hacking the developing world the same way it hacked America’s political political system:

https://prospect.org/economy/the-china-hack-and-how-to-reverse-it/

Yes. Succinct but to the point.

I follow up with some more…

Societies are assemblies of extremely complex systems interacting non-stop with one another. And the fact is that Western societies and China’s society are operating along the lines of different paradigms :

— their cultural fields have nothing in common

— their economic fields operate according to different textbooks

— their social field is directly impacted by the place reserved to their capital holders in the public decision making process. Seen the radical difference in the nature of the capital ownership of both their social realities on the ground are radically diverging. The handling of Covid-19 is a case in point. The Chinese citizens are reading this as such and consequently their rates of appreciation for the actions of their government are increasing to unheard levels of satisfaction… (95% presently).

— their relations with the rest of the world are grounded in opposite perceptions of “the other” and so their approaches toward the rest of the world have nothing in common.

In light of the rather fundamentally different approaches of these societies it is imperative to understand that the categories, defining the working of one, are not applicable in defining the working of the other. In other words using Western categories to understand China is ludicrous.

In my view we have entered in a very volatile historical process that will not stabilize before — or one of them collapses under her own contradictions — or China’s economy grows so overwhelmingly bigger than Western economies that the fact is simply registered by all and life continues under a new paradigm.

From where I sit here in Beijing I think that the Chinese leadership is strategizing the latter. And consequently its outside interventions are bound to a momentary slow down… The belt and Road until now was in a phase of testing and it was decided at the time of its launch that the strategy relating to the project would be finalized during the year 2021 ! This is a whole century project ! How many in the West are taking this publicly available information into account ? In China’s calculus the first priority with the outside is the unification of East-Asia and so the rest of the world should await less imports and less investments from China in the coming years.

The priority for the next 5 to 10 years is an internal strengthening of the nation economically, technologically, culturally, and in daily life while prioritizing the following outside projects :

1. East-Asian cultural commonalities and economic inter-dependencies will be strengthened by absorbing the cost of a trade balance deficit with ASEAN, Korea and Japan

2. there will be an intensification of trade and diverse science and tech cooperation projects with Russia

3. the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) remains a priority

4. the participation in the development of Iran and Irak is an extension of the CPEC priority. Yes China needs to secure its procurement of energy over the coming years. It has announced getting out of dependency from fossil fuel by 2060. This leaves thus 4 decades of needs to be fulfilled by imports of oil and gas.

Pettis’ take on the above:

https://twitter.com/michaelxpettis/status/1336249094520659969

Thanks

Pettis doesn’t really disagree with the points above. He adds some historical background and some interesting specifics regarding Venezuela.

Yves wrote in a footnote: “It was effectively recycling European flight capital back to Europe.”

Interesting. Do you have links for further reading?

I’d also be interested in checking something out, if Yves has a piece of source material she’s thinking of.

But, it may be that she’s making a more simple point about the US balance of payments issues.

With the US being the world’s leading exporter at the time and its customers (Europe) not having any money or capital because it was either obliterated in the war or liquidated and stashed in the US. There had to be SOME kind of vendor financing scheme to finance capital investment and consumption to rebuild.

The US had a large export/current account surplus and needed to have a corresponding capital account deficit to balance. If not, the world economy would have rapidly found itself back-sliding into Depression-era style crises of inadequate demand. Charles Kindleberger’s old book on this helped to really lay out the high level framework of imbalances of capital flows, currencies and commodities.

The Marshall Plan should be viewed in the context of the Bretton Woods arrangement, which was the most successful global financial architecture ever deployed in the history of the world.

I’d also suggest that Belt and Road was a always a harder project to implement successfully.

Marshall Plan involved a lot of rebuilding what people already had once done before.

China is trying to develop export markets that haven’t previously been developed like this.

Is it possible that China’s development lending is/was their attempt at the US’ Super-Imperialism, as described by Michael Hudson?

Michael Hudson actually talked about this with Pepe Escobar this morning on a Zoom call that I hope is posted soon. If I recall correctly, he said China is fundamentally interested in opening trade routes and doesn’t want or expect that the infrastructure to create profit in and of itself, which is what the FT can’t comprehend or analyze. I’d say less Super-Imperialism, and more wanting to create a safe space for trade and commerce free of US dollarization. So the intent is not to squeeze the countries for their debt or shake them down but invest so they can create trade opportunities. But hopefully the talk (“Rent and Rent-Seeking”) will be up soon so you can listen to him yourself.

“I’d say less Super-Imperialism, and more wanting to create a safe space for trade and commerce free of US dollarization. So the intent is not to squeeze the countries for their debt or shake them down but invest so they can create trade opportunities. “

Imperial projects come in a variety of different designs and flavors. China’s actions have been more and more brazenly about control and influence in recent years. Just because they’re trying to carve out their own regional bloc (away from USD), doesn’t mean what they’re undertaking is NOT an imperial project. It’s just that they’re setting it up a bit differently.

As Yves points out, they still have the challenge of figuring out what to do with all that USD that doesn’t involve just wasting it (at least not more than they are already wasting).

thanks for sharing this

In that case, presumably a jubilee from China to its debtors is forthcoming *cough*

How much was vendor financing, and how much was checkbook diplomacy in the form of vanity projects?

My favorite example is Costa Rica’s national soccer stadium, where it was both. Use Chinese construction companies, import Chinese labor, and use Chinese suppliers – all right before switching diplomatic relations from Taiwan and signing a trade deal.

I’m sorry but This is difficult to understand.

While a very, very large infrastructure project that spans the globe could be expected to experience cost over runs and financing issues are there no other considerations for the Chinese government ?

Could it be that the Chinese are sitting on a pile of cash with limited places to invest ?

Could it be that the Belt and Road is an effort to continue global dominance in some strategic materials ?

Could it be that the Chinese seek a ready outlet for their burgeoning manufacturing capacity ?

In short this may not be the usual mere accounting / banking / financial transaction.

Based on published data from the World Bank for the years from 2011 to 2019, the decision by China’s leadership to curtail its Belt & Road and foreign infrastructure and resource development loans and spending likely has much to do with the growth in China’s external debt, declining Foreign Direct Investment in China, the drawdown in China’s foreign currency Reserves relative to its external debt, and intermittent shortages of access to eurodollars in the global financial markets.

China also needs imports of foreign-sourced commodities to support its manufactured exports. A portion of those imports are likely denominated in US dollars. Generally underappreciated issues in my opinion.