Yves here. This post summarizes what looks to be an important article in the Stanford Technology Law Review, which describes how Google’s dominance in online ads results from practices that are forbidden in other markets. At a time when lawmakers and attorneys general are looking for ways to curtail Google’s power, the idea presented here, of barring Google from engaging in conduct that it already outlawed in financial markets, is elegant and would be effective.

The days of Google having “Don’t be evil” as a motto are so far in its past that using it as a taunt has lost its sting.

By Dina Srinivasan. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

The United States and many other countries are investigating Google for violating domestic competition laws. Right now the U.S. Department of Justice is grabbing the most headlines with its decision to file formal antitrust charges against Google for monopolizing the search and search advertising markets. But the Department, U.S. states, and foreign governments continue to investigate the company for its dominance of online display advertising markets.

My new paper “Why Google Dominates Advertising Markets,” supported by INET and publishing today in the Stanford Technology Law Review, analyzes the structure of advertising markets, why Google dominates them, and what can be done.

In a nutshell the case is simple: Online ads are traded on centralized electronic trading venues and Google maintains an iron grip on this vast market by engaging in conduct that lawmakers routinely prohibit in other electronic trading markets.

At the heart of the story is an industry in the midst of transformational change. Ads used to be bought and sold by Mad-Men types over two-martini lunches off Madison Avenue. Today, about 85% of all online display ads in the U.S. are bought and sold electronically and at high-speed through centralized trading venues, which the industry calls “exchanges.” The shift to electronic trading started in 2004, the same year the New York Stock Exchange migrated from a floor-based exchange to electronic trading.

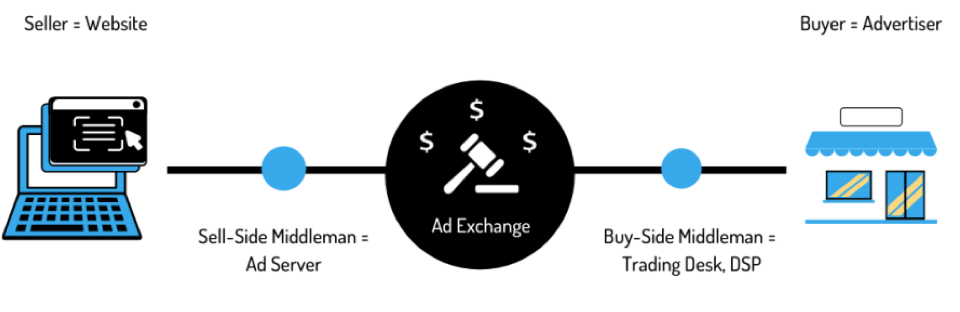

The parallels between Wall Street and advertising do not end there. To buy a share of Tesla on the NYSE, one has to go through a broker. Advertising markets also have middlemen and, in contrast to the world of Mad Men, middle women. To buy ad space on The Washington Post from Google’s advertising exchange, an advertiser like Proctor & Gamble has to go through a middleman, called a trading desk or demand-side software (DSP). A publisher like The Washington Post also goes through a middleman to sell on exchanges. The software that publishers go through is called an ad server.

The network of market transactions looks rather like this:

Google dominates at each and every step in this set of markets. The giant concern is that Google operates the largest advertising exchange, the largest sell-side middleman that publishers use, as well as the largest buy-side middlemen that advertisers use. More often than not, for any given transaction on its exchange, Google also sits on both sides—the sell-side and the buy-side. The equivalent in the U.S. would be if the firm that operated the NYSE also owned and operated Goldman Sachs—with no formal rules to prevent conflicts of interest management.

The entire lifecycle of an ad trade happens in the blink of an eye. When you visit a website like USA Today or Le Monde, the publisher’s sell-side middleman quickly routes the publisher’s space to one of several exchanges that line up potential advertisers. Each exchange initiates an auction by sending trading signals to the buy-side middlemen that have a “seat” to bid on behalf of advertisers. Those middlemen must return a bid back to the exchange within about one to two-tenths of a second. After that, the exchange closes its auction and chooses a winning bidder. Le Monde’s sell-side intermediary then picks up the advertisement with the highest exchange bid and returns it to the user’s page before the page has finished loading. All the user sees is the winning bidder’s ads—maybe ads for Nike next to an article about workouts.

In addition to breaking down the market’s structure, my research traces how Google dominates merely by doing things that lawmakers flatly prohibit in other electronic trading markets. The comparison with the financial world is stark: Google’s conduct includes behavior similar to front-running, the preferential routing of order flows, and even insider trading. There are even speed races that echo the narratives of high frequency traders. The parallels highlight a major question: Can we fix the market by simply borrowing a few core rules from Wall Street?

For example, Google entered the exchange market late but employed a familiar tactic to quickly grow its exchange to number-one. When Google entered the exchange market in 2009, it faced competition from ad exchanges belonging to juggernauts like Microsoft, Yahoo!, and other Silicon Valley upstarts. To edge out exchange competition, Google leveraged its control of the sell-side, DoubleClick, which Google acquired in 2008. Specifically, Google made DoubleClick start preferentially routing websites’ ad space to Google’s new exchange and blocked them from simultaneously trading in rivals’ exchanges. Within a few years, Google’s exchange rose to number one to transact the most volume. Starved of liquidity, other exchanges closed their doors.

Brokers in financial markets can similarly distort or foreclose competition in exchange markets. In finance, Barclays in ’09 developed a similar strategy to promote its own dark pool exchange in the market. However, Barclays eventually answered to the SEC and the New York Attorney General. In financial markets, we make brokers and exchanges manage any conflicts of interest. When brokers like Barclays run off-exchange trading venues, they are required to manage conflicts through firewalls and routing rules. Companies that operate that operates a public exchange like the NYSE cannot also operate on the buy- or sell-sides.

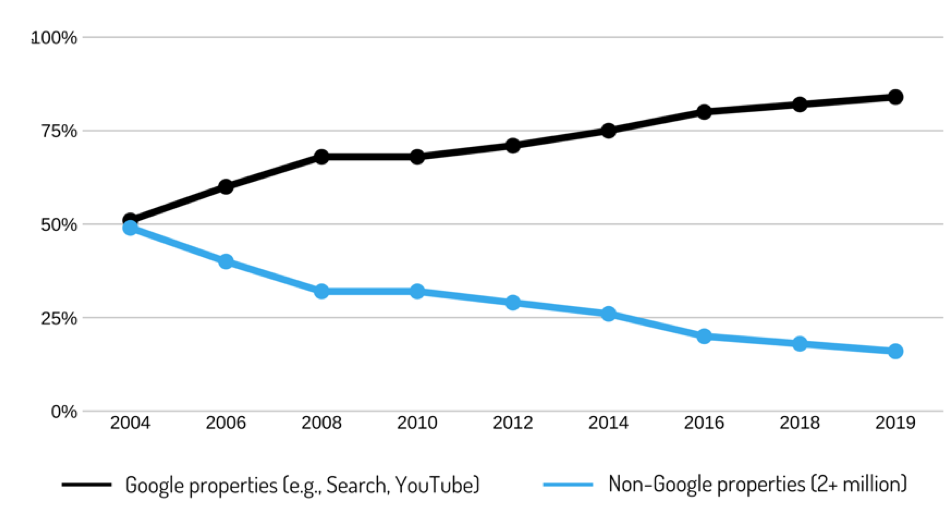

Google also uses its dominance of the buy-side of the market to steer advertisers to Google’s own properties, including Search and YouTube. Over the last ten years, more and more advertising dollars flow through Google’s buy-side flow to Google properties rather than the 2+ million other websites and apps that also sell their ads through Google. The following figure captures this trend.

Image Source: Why Google Dominates Advertising Markets: Competition Policy Should Lean on Financial Market Regulation, at 24 STAN. TECH. L. REV. 56 (2020).

Competition authorities, publishers, and advertisers also look quizzically at Google’s dominance because ad trading costs remain suspiciously high. In theory, electronic trading should push transaction costs (and dealers’ spreads) down. However, in advertising, transparency is a challenge. Some authorities estimate that middlemen take 30 to 50% of every trade. When a local car dealership uses Google’s buy-side to purchase ad space from Google’s exchange, Google does not tell that advertiser what the ad space ultimately cleared for or how much Google keeps as its share. Google also does not disclose to the publisher on the other end of this trade how much the advertiser paid to purchase the publishers’ inventory.

Small businesses—the backbone of an entrepreneurial economy—reach consumers through online advertising. If these businesses pay high trading costs, consumers pay those costs in the form of higher prices for products and services. Hard hit by the global Covid-19 pandemic, consumers and small businesses are already stretched thin. At the same time, ad revenue is the primary source of income for most online content creators, including news operations. If publishers make significantly less selling their ad space, the press, and by extent democracy itself, are victims.

Whether fixes come through antitrust litigation or legislation, we can fix problems in the ad market by leaning on time tested principles of financial market regulation. First and most obviously, we need to manage conflicts of interest. Firms that operate an exchange, or buy-side or sell-side intermediaries, should divest conflicting operations or manage conflicts through strong firewalls. Insider trading type rules can complement firewalls to prevent exchanges and intermediaries from abusing their privileged access to inside information. Additionally, advertising exchanges can be required to provide all bidders with equal access to data and speed—a position the SEC recently strengthened with respect to financial exchanges. Finally, the sun needs to shine in this byzantine trading market: Firms should be required to disclose information about their conflicts, prices, and spreads. By relying on these core principles that are well accepted in financial markets, we can make modern ad markets become more competitive to the lasting benefit of entrepreneurs, publishers, and consumers.

At some point we probably should ask ourselves and our leaders, why these tech giants are allowed to do things that would have gotten a normal person thrown in jail before the internet. And shame on the brands that use these privacy nightmares to hawk their goods.

Why are people OK with these companies “disrupting” industries that took centuries to evolve – hollowing the labor costs and hoovering up all the P&L? It’s not capitalism as Schmidt protests, but rather a smash and grab. And the thieves are jumping ship:

https://www.cnbc.com/2020/11/09/eric-schmidt-reportedly-applied-to-become-a-citizen-of-cyprus.html

Having worked for a non-Google demand-side platform (DSP) for several years, I can confirm that this is an accurate description of the way ad tech works.

I have always maintained that the most cost-effective way to fix antitrust problems in big tech (when this applies) is to strip founders shares of their outsize voting status.

The founders are techno-libertarians who behave with the Ayn Rand style ethics (now there is an oxymoron) of “Disruption” (or move fast and break things).

When you look at the post internet giants of tech, they have achieved have regulatory arbitrage (PayPal, Amazon, Facebook), subsidies (Amazon), anti-competitive behavior (Google), unethical behavior (Facebook, Paypal), breaking the law (PayPal, Uber, Lyft, AirBnB), etc., there is a culture of lawlessness that flows from the top.

If the founders lose their extraordinary voting rights, then adults can intervene.

I am not saying that this is a complete solution, but it is a good first step.

> strip founders shares of their outsize voting status.

Sounds like a good idea!

Thanks.

This could be a good idea for other reasons.

But it does nothing to eliminate the incentives for these corporations to gain by these behaviors.

Corporations don’t have incentives, people do.

If you look at Facebook, for example, you see that the anticompetitive behavior comes straight from the top: Zuckerberg, and it comes from his technolibertarian.

Removing his control of his baby serves as a very real (and also very cheap, the price difference to be reimbursed would be perhaps a few percent of the share price).

Additionally, this is something that could be done with a stroke of a pen, while the details on spinning off things on Instagram could take months or years.

I am saying that it is a good start, because its effect is immediate, and it will scare the hell out of the folks idolize disruption and moving fast and breaking things, so it will serve as a deterrent.

You still want to break up the firms, and in Facebook’s case, end 3rd party tracking and its use to register for external accounts, but it’s a start.

If those in power can evade the First Amendment by outsourcing censorship to digital monopolies, then why would they have any interest in regulating the practices by which said monopolies are maintained?