Yves here. Some readers may regard debates within the economic academy as quaint. That’s a huge mistake. Economists are the only social scientists with a seat at the policy table. Mainstream theory, even when it is demonstrably false, still drives key government decisions, such as the aversion to deficit spending. As we’ve written, the British government ran sustained deficits during the country’s most prosperous decades, in its Industrial Revolution. The US has run consistent deficits; the few times it hasn’t either produced recessions or set up financial crises (the Clinton era surpluses led to a need somewhere in the economy for another sector to dis-save, as in borrow, to prevent the economy from contracting. That wound up being households via mortgage debt. Personal savings plunged during the Clinton Administration and even was negative in some quarters).

The fact that the Washington Post depicted an article by Jason Furman and Larry Summers pumping for deficit spending as evidence of an “intellectual revolution” shows how bad a grasp most commentators have on economics. As the post by Jamie Galbraith describes long form, the Furman/Summers argument was incoherent and relied on the “loanable funds theory” (loans come from existing savings and are therefore limited; interest rates serve to balance supply and demand) that was debunked by Keynes nearly 100 years ago.

The reason it is important to call out this sort of chicanery is that the Furman/Summers gymnastics are an effort to shore up a clearly failed paradigm. As we described long form in ECONNED, bad economic theory, both mainstream economics (the macroeconomics used in policy-making) and financial economics, produced the global financial crisis. Yet these bad ideas are still widely accepted even though they’ve produced even more inequality, low growth, under-investment, and excessive financial speculation.

Economics fancies itself to be a science and is in denial that it’s in the midst of a crisis. From the Wikipedia write-up of Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions:

As a paradigm is stretched to its limits, anomalies — failures of the current paradigm to take into account observed phenomena — accumulate. Their significance is judged by the practitioners of the discipline. Some anomalies may be dismissed as errors in observation, others as merely requiring small adjustments to the current paradigm that will be clarified in due course. Some anomalies resolve themselves spontaneously, having increased the available depth of insight along the way. But no matter how great or numerous the anomalies that persist, Kuhn observes, the practicing scientists will not lose faith in the established paradigm until a credible alternative is available; to lose faith in the solvability of the problems would in effect mean ceasing to be a scientist.

So the Furnam/Summers sophistry in the interest of a good cause, justifying Covid deficit spending, does damage by defending destructive ideas way after what should have been their sell-by date.

By James K. Galbraith, Lloyd M. Bentsen Jr. Chair in Government and Business Relations, University of Texas at Austin. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

The new paper “A Reconsideration of Fiscal Policy in the Era of Low Interest Rates” by Jason Furman and Lawrence Summers (hereafter, FS) is most sympathetic from a policy angle. The authors drive toward their conclusion that the United States can afford the large-scale emergency programs and federal investments, even if “deficit-financed,” that the country needs, at least in the near term. On this point one cannot complain.

This note will address the underlying economics. They are a mess. To be blunt, the FS paper is built on a pastiche of obfuscations, entirely unnecessary to support the conclusion. Their effect, and one may reasonably surmise their purpose, is to make the argument without appearing to question the longstanding “mainstream” theory of interest rates. That theory, which has been the source of deficit- and debt-hysteria for several centuries, in turn underpins the newly-proposed FS debt-service-to-GDP ratio criterion for fiscal policy. It will be nothing but a source of trouble, unless disposed of.

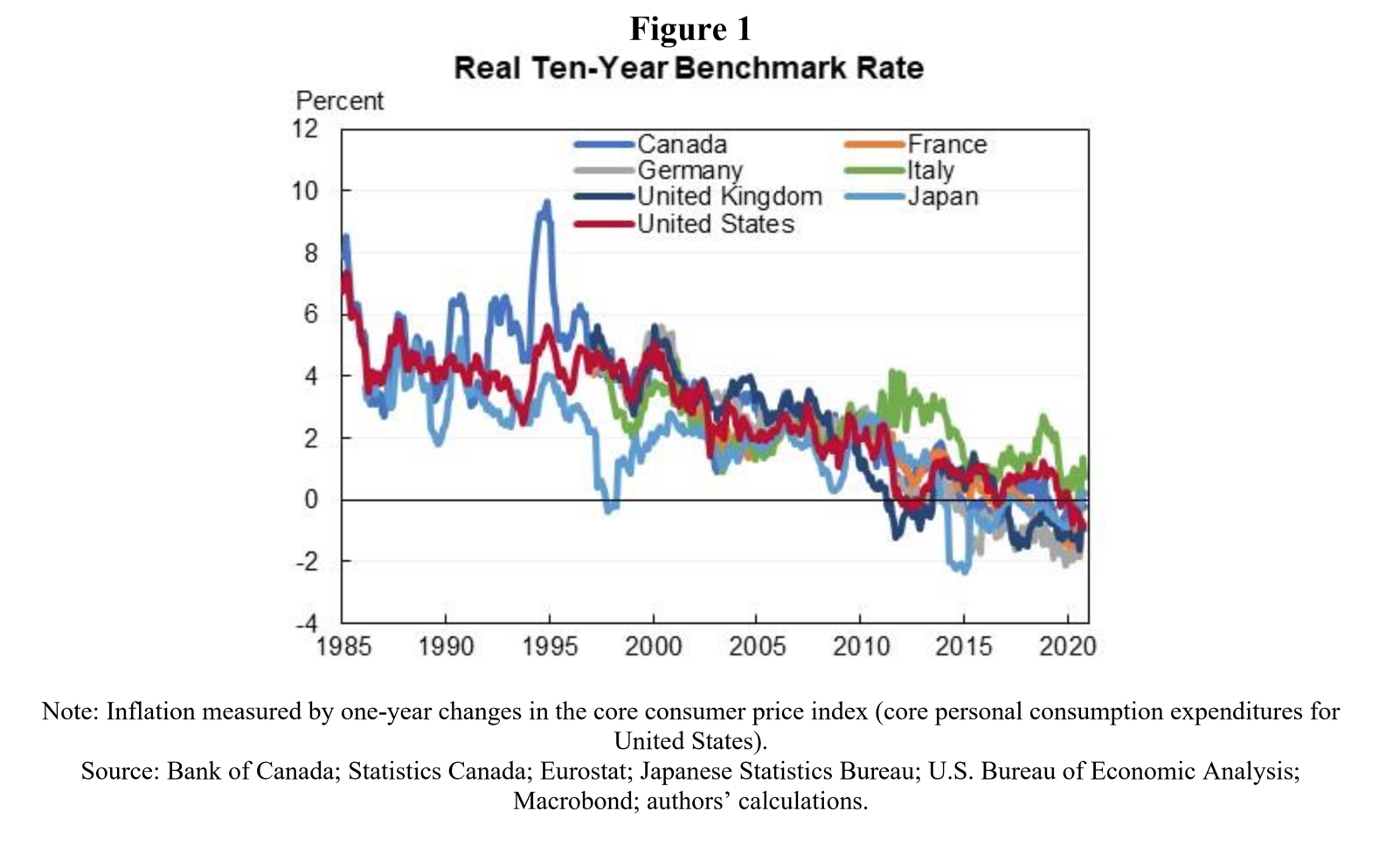

The core FS argument turns on a decline in “real” interest rates – defined as the stated (“nominal”) rates at various maturities – minus the expected rate of inflation over the same period. Since expected inflation has not risen by any known or alleged measure, this is the same thing as saying that interest rates on US Treasury bonds have fallen across all maturities, which they have (Figure 1). The question is why? To answer, FS rely on a textbook-standard theory of interest rates, known as the “loanable funds” theory, as they acknowledge on page 15.

Loanable funds is a supply-and-demand theory. It holds that there is a supply of funds, given by available savings in global (or possibly, national) capital (financial) markets, and a demand for those funds, which comes from either the public or the private sector. FS note that the demand for funds – at least recent government demands in the form of public deficits – has risen dramatically. Their theory therefore requires one of two things, perhaps in combination: a vast offsetting, autonomous increase in the supply of savings (global or national), and/or a reduction in the private demand for savings, in the form of privately-issued debt.

As to what specifically happened, FS state that the “precise reasons for the decline in real interest rates are not entirely clear” but they suggest “structural changes in the economy” that may or may not include “increasing inequality, uncertainty and the use of information technology.” When the present author was in graduate school, this was known as “hand-waving.”

There are two problems with the argument. The first is that there is no long-term trend in US private savings, nor in the import of savings from overseas – which would show up as an increasing US current account deficit relative to GDP – nor in the ratio of private debt to GDP. These numbers do fluctuate, but in ways that in no way coincide with the long-term decline in interest rates. The empirical root of the FS argument is therefore wholly imaginary.

The second problem is more theoretical. One way to put it, is to say that “loanable funds” is a theory of the spot market. It is a theory of the supply-and-demand of today’s available savings and today’s demand for funds. In this, the question of maturities is secondary. There are not separate loanable-funds markets for overnight paper, ten-year bonds, and twenty-year bonds, and so the loanable funds theory has no explanation for the difference between short and long-term interest rates – for the yield curve. But this is precisely what FS are trying to explain.

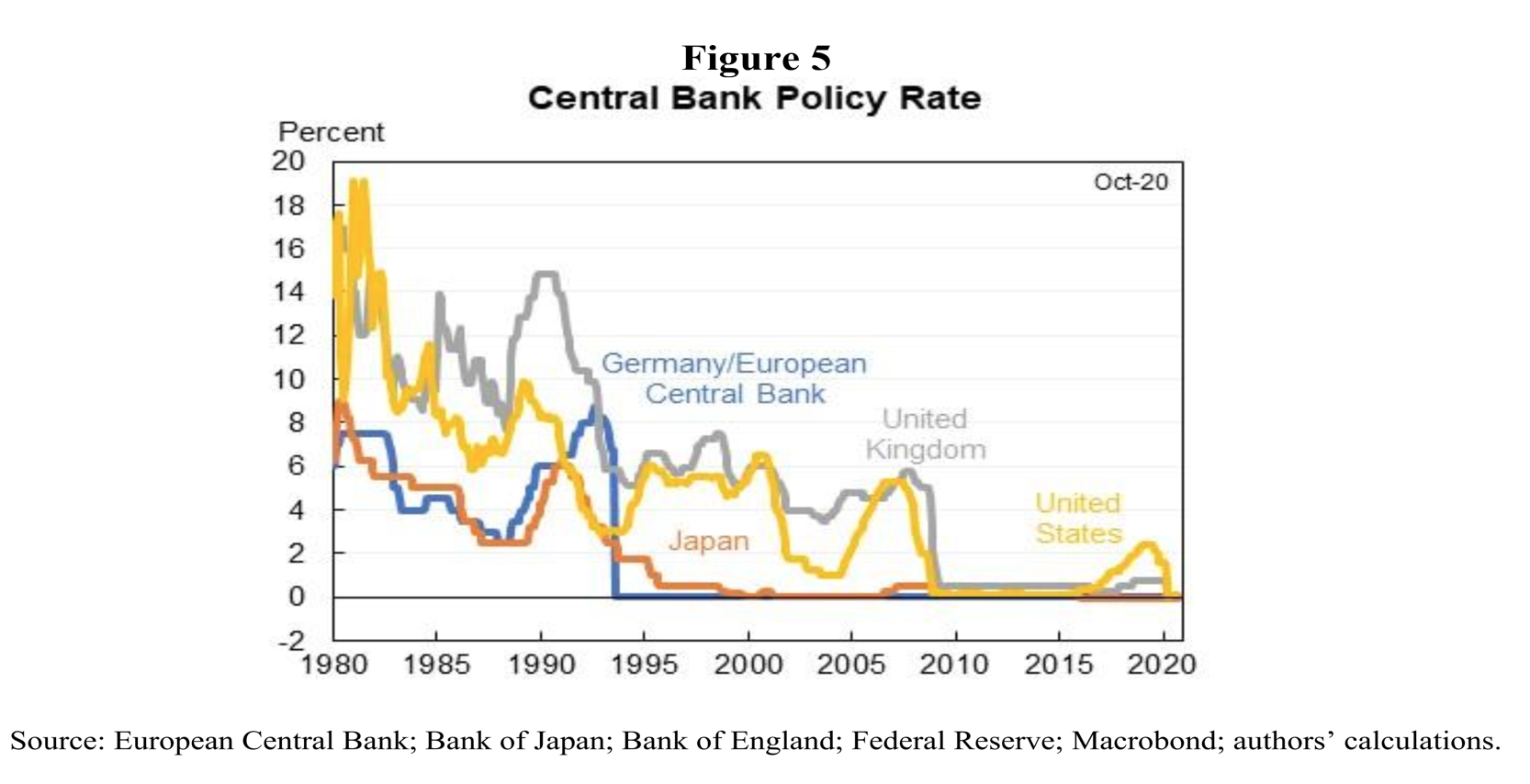

Of course we already know what determines the short-term interest rate. And we know that that determination has nothing to do with any supply of savings or demand for funds. The overnight rate on bank reserves – called the “federal funds rate” in the United States — is set by the Federal Reserve. That is what the Federal Reserve, specifically its Open Market Committee, does for a job. There is no issue about this, it is simply a statement of fact. Short-term interest rates are low because the central bank has set them at a low rate, here and abroad (Figure 5). End of story.

What then about long rates – say the rate on a ten-year Treasury bond? Here bond investors do play a role. What they do, is decide how to hold their available funds – whether in short-term paper, longer-term Treasuries, or private paper – according to their own calculations and preferences for risk and reward. And since interest rates on long-term instruments might rise at some point in the future, the price of existing bonds, paying a fixed coupon, might fall. So there is a small amount of capital risk, which could face an investor who needed to liquidate such an instrument. To compensate, investors typically need a premium over the short-term rate. Keynes called this the incentive to “not-hoard” purely liquid funds, e.g. cash or its equivalents.

How big a premium? That depends on what investors think is going to happen to interest rates – and specifically to the short rate that the Federal Reserve controls. In other words, it depends on guesses about the future of interest rate policy. Those guesses rely – because they have nothing else to rely on – on the history of short-term interest rates. If short rates were recently high, and have recently fallen, substantial opinion may expect them to rise again. And so the longer-term rate will sit well above the rate on federal funds or Treasury bills. That was the case in the 1980s and 1990s when the trend toward lower long-term interest rates got underway.

But now, for many years, short-term interest rates have been very low! FS point out that the federal funds rate has been at zero – as low as it goes – 59 percent of the time since 2007 and 38 percent of the time since 2000. Expectations, and therefore longer-term rates, have adjusted. No deeper explanation is required.

There is however one further aspect to the formation of expectations, undoubtedly obvious to investors if not to economists or public officials. Because it is based on long-term expectations, the long-term bond rate is sticky. It falls more slowly than the short rate, and it rises more slowly when short rates are pushed up. But when both sets of rates are very low – the present case – any rise in the short rate pushes that rate toward the long rate, or above it. This makes buying any form of low-risk long debt unattractive, and tends to collapse financial markets, drive up the dollar, and generally to produce havoc and recession. This is something central banks do not like. And so central bankers are stuck – they have no room to lower rates or to raise them. The expectation of a low short-term rate far into the future becomes glued to the zero bound, or very close to it.

FS therefore arrive at a correct conclusion – interest rates will remain low indefinitely – by a route that requires them to argue that the world has changed in some fundamental, relevant (“structural”) way, for which no evidence exists. The effect is to leave in place an incoherent theory of interest rates, which does not even claim to explain the phenomenon – low long-term rates – that their paper is trying to address. But a correct and viable explanation, as above, of a form long-ago explained carefully by no less than John Maynard Keynes, is readily available and wholly sufficient.

The theoretical issue is important, because it bears on FS’s proposal for a debt-service-to-GDP ratio test for future fiscal policy, and on interest rate projections on which the proposed rule depends. We now turn to these.

Under loanable funds, anything can happen to interest rates down the road. Savings (global or local) might dry up. Business investment demand might surge as employment returns to its “natural rate”. Either of these events would put upward pressure on interest rates, reversing the low-interest environment and making debt service far more “costly” than projected. And expectedinterest rates can rise at any time, if the designated forecaster believes any of these events are likely.

With a view that things might change, FS propose an alternative to the Debt/GDP ratio as a guideline for future fiscal policy. This is that the “projected” ratio of public debt service to GDP “not spiral upwards over the period,” which they operationalize with a proposed ceiling of 2 percent of GDP.

The ratio of debt-service-to-GDP is (obviously) just the ratio of public-debt-to-GDP times the interest rate, now taken as the average rate on the whole portfolio of federal debt. As FS note, the debt/GDP ratio “asymptotes” [sic] to a constant value whenever the rate of growth (g) of the economy is greater than the average interest rate (r). Thus to keep debt-service-to-GDP low in the long run, it is sufficient that g>r and that r be kept low – if necessary anchoring the short-term rate at zero. But as history shows and as everyone knows, controlling the short-term rate is entirely within the central bank’s power. Thus the FS criterion boils down to maintaining a positive growth rate and an easy money policy; it has nothing to do with the budget deficit, except as deficits may be needed for growth.

The FS criterion as stated may therefore prove fairly harmless. But does it make sense as a criterion of “fiscal stability”? No: it adds nothing to the discussion. The US government can comfortably pay any level of debt service, at any time, now and in the future, even if GDP falls or interest rates rise. The level of debt service in relation to GDP is just as irrelevant as the debt/GDP ratio. Adding a financial “rule” as a constraint on what now needs to be done, accomplishes nothing useful. And this one opens the door to pointless austerity later, based on some specious projection of rising interest rates.

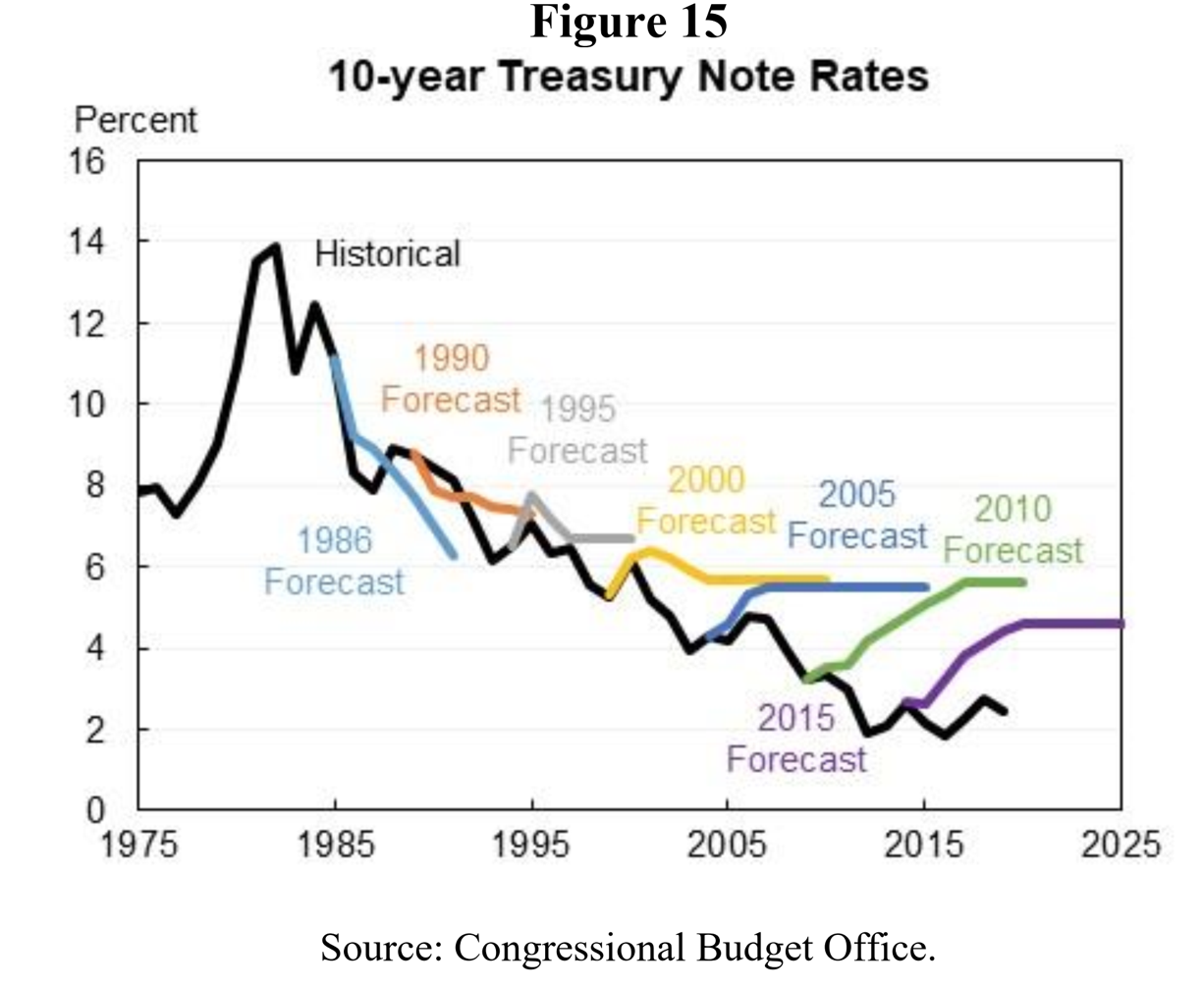

The problem is that specious official predictions of rising interest rates are entirely normal! FS include a very useful chart (Figure 15) showing the persistent – and ongoing! – forecasting failure of the Congressional Budget Office with respect to interest rates. CBO has persistently overestimated future interest rates for decades. FS note that the errors have been growing over time, but they do not point to the obvious reason, immediately visible in their chart. For at least 15 and possible 20 years, as the ten-year bond rate marched steadily downward, CBO never changed its long-term interest-rate forecast! The forecast remained stuck, for no rational reason, at a return to 6 percent. (CBO has since lowered their projections.) This ridiculous forecast was a main source of hyperventilating Washington and media predictions of debt-service explosions and debt debacles for many years.

In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith has a discussion of the repeal of Elizabethan laws prohibiting the taking of gold and silver “forth of the kingdom.” He explains that the arguments made against those laws, which involved substituting instead attention to the balance of trade, were “partly solid and partly sophistical.” “Such as they were, however, those arguments convinced the people to whom they were addressed… they were addressed by merchants to parliaments and to the councils of princes, to nobles, and to country gentlemen; by those who were supposed to understand trade, to those who were conscious to themselves that they knew nothing about the matter… these arguments, therefore, produced the wished-for effect… From one fruitless care, [the attention of government] was turned away to another care much more intricate, much more embarrassing, and just equally fruitless.”

Jason Furman and Lawrence Summers are in much the same position as those 17th century merchants described by Adam Smith.

For reference, relevant charts from the FS paper:

re: the growth of household indebtedness during the Clinton era surpluses,

Back in the late ’00s, I saw a stunning graph on “Mortgage Equity Withdrawal” at the Calculated Risk weblog (which I regard fondly as it was how I encountered NC, which was then featured in its ‘blogroll), that indicated that — IIRC — at the peak, MEW was about 7% of GDP

CR still reports on MEW, and a recent graph shows it as a ratio to personal income

https://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2020/09/mortgage-equity-withdrawal-increased-in.html

peaking at about 9% in the period in question.

—

The thing that that I found most persuasive in my early acquaintance with MMT (which was from Randall Wrays “MMT Primer” at the NEP website, was the argument that public deficits generally respond to and in that sense are produced by private savings decisions. I suppose that the Clinton surpluses might be a counter-example; imposed public austerity induced private actors to dis-save to maintain consumption.

I watched this quite closely when it came out. A striking shift in stance from people like Summers and Rogoff although you couldnt tell by watching. Remember Rogoff co-wrote with Carmen Reinhart quite a well quoted paper on the impact of financial crisis on debt and real economies, and his big takeaway was how important a 90% debt/gdp ratio was and why excess debt was a terrible evil.

I agree the failure to shift stance on the theory is important for economics. But for shameless bond traders like me it doesnt matter. There will be identity politics and there will be fiscal headroom. Thats what the very serious people are telling me.

@Harry

December 9, 2020 at 10:47 am

——-

I think it’s worthwhile to note that the Rogoff-Reinhart paper was totally debunked due to errors in the construction of their Excel spreadsheet (!), as well as conflating countries that issue their own currency with countries that use a currency they can’t issue (Euro members).

Of course. Carmen R’s career was devasted by that embarassing error.

;)

Economics seems to be the only discipline where one can exhibit total incompetence and still be in high demand, or is it because of the incompetence?

Larry’s innocent sounding book is coming out just in time to ingratiate him with Biden’s administration and possibly with Yellen. A backstop to their easy money tendencies? Or intimidate them? But if it has an austerity time-bomb nested in its equations it is financially self serving for Larry. For one, it seems to claim that private banking is the best judge of dangerous levels of inflation based on easy money, aka low interest debt. This at a time when fiscal spending is front and center as a policy. So how might all this fit in with Larry’s interest in Libra? A private money scheme that needs the dollar to roll. Does this give him a soap box to maintain the good-old strong dollar? Can’t have clean drinking water – it would weaken the dollar. A position for austerity that other like-minded people, private-money speculators can embrace and promote? And is it a good thing for Libra to be pegged to a strong dollar? Instead of say, the Swiss Franc? Or maybe because of the Swiss Franc. Or maybe something else Larry’s all mixed up with these days Larry is innocent like a fox.

The US government can comfortably pay any level of debt service, at any time, now and in the future, even if GDP falls or interest rates rise. Jamie Galbraith

Then that certainly includes NEGATIVE rates too and indeed ethical considerations concur for the inherently risk-free debt of a monetary sovereign like the US, UK, etc:

1) The most such debt should return is ZERO percent minus overhead costs = NEGATIVE.

Otherwise we have welfare proportional to account balance, a moral abomination.

2) Shorter maturities should cost more (more negative interest) with the shortest maturities (e.g. “bank reserves”) costing the most.

That said, it can be argued that individual citizens have an inherent right to accumulate and use fiat FOR FREE up to reasonable limits.

Besides, even the pro-bank MMT School recommends a permanent ZIRP, on moral grounds, though they undercut that stand by proposing OTHER privileges for the banks such as unlimited, unsecured loans at ZERO percent interest and unlimited deposit guarantees FOR FREE!

But isn’t it nice to know that a monetary sovereign can afford unlimited welfare for the rich?

Personally, I think the economics profession needs serious reform. If my profession was so wrong so often, there would be dead people and a very mad public. I know there are dead people out there because of our economic polices, but economics is such pseudo-science, they just ignore reality.

Start by calling it political economics so that everybody clearly understands we are being feed political views disguised as “science”. It isn’t science.

Economics was originally called Political Economy. Compartmentalization became the preferred method to bend minds away from connecting big picture patterns. A hundred and fifty years ago, the classical (political economy) synthesis pointed to freeing the market from unearned income and predatory finance. Economic history has been dropped as a requirement for Econ majors tho… gee shocker.

Academic economics is mostly a public relations tentacle of the wealth defense industry.

wealth defense industry….+1

Requirements for my econ major:

101, macro, micro, micro 2, econometrics, and 3 electives. Plus Calculus and Stats. very mathematically oriented. i presume because thats where the money jobs are and in turn the donations.

There are a few bright spots with behavioral classes being far and away the most popular ones. The omission of the relationship between private savings and deficits was a notable part of macro. It was mostly an exploration of Keynes and neoclassical modelling. No MMT or coverage of unemployment causes and function as wage suppression.

I agree with your post. But US interest rates aren’t actually low from an international perspective. Since low rates are not just happening in the U.S. isn’t this evidence to ‘suggest “structural changes in the economy” that may or may not include “increasing inequality, uncertainty and the use of information technology.”’

I guess the alternative is that every other Fed equivalent agency around the word is similarly holding rates low. Is this true? I confess I’m not up to date on international monetary policy

Yup. It’s competitive devaluations, “least dirty shirt” and lower for longer as far as the eye can see among central banks all over the world

The fact that interest rates are generally and consistently lower outside the u.s. is not an accident. If you read Nomi Prine’s (sp?) Collusion, you will find that this is a very political outcome.

The question then becomes why is this a desirable political/economic outcome? Could it be that this supports the dollar?

Any thought?

Furman said on twitter a couple weeks ago that cancelling student debt would be regressive and would have a negligible multiplier. For which (and for the contrast between his daft take and his pompous credentials) he was rightly ridiculed in the thread.

But, he is who is being put in a seat at the table. To be expected. Summers – doesnt even merit a comment.

Their daftness is not to be taken seriously as an economic position. It is to be taken as a shamanic position defending financial and power interests.

If you follow his assumption it seems pretty reasonable you’d have a negative multiplier. Loan forgiveness is considered “income” so you receive a one time very large tax bill–this more than offsets the minimal monthly and even annual loan payment expenses as the loan is amortized over decades. It does seem like a strange assumption to make, but is interesting to consider. Certainly easy enough for Congress to get around if they wanted

To his larger point about the policy being regressive: while its certainly not regressive when compared to, say, the 2017 tax cut it would be regressive compared to policies that benefit everyone, even those who didn’t go to college, like Universal Healthcare. I’m certainly not trying to put words in his mouth and say that was what he meant when he tweeted–but I don’t take issue with the tweet

Yes. Everyone should receive the payment.

I suppose am one of those readers who regard debates within the economic academy as quaint. Though economists may be the only social scientist with a seat at the policy table — which economists are given those seats appears very much related to how well their advocacy supports what Government has already been directed to do by its owners — not us. I remain deeply cynical after the CARES Act and the subsequent post CARES non-acts.

Failure in the world is not a criterion for success in the academic world of economics. Failure in the weight of arguments presented does not appear to be a criterion for success when arguing in a world of academic debate where the judges seem to have prejudged the debate. Those economists sitting at the policy table or picking up ‘Nobel’ prizes seem unaffected by their failures in the world and failures in the weight of their arguments. Otherwise, why must someone of Jamie Galbraith’s intellectual stature bother debating with the likes of Furman/Summers.

It’s important to understand why their logic is wrong in detail, however I agree it is somewhat wasted energy when done on a large scale because it allows Furman/Summers and the like to dictate where the field goes. I am more on the side of dismissing them as frauds to usher in a new era just as political as the profession. Following the likes of Kelton and Mosler who are able to effectively convey MMT to the average person, the movement of capital and labor is much more straightforward than it is made to seem, at least in a macro sense. As pointed out at NC thousands of times, the system is made to seem more complex than it actually is, especially with explanations such as Mosler’s car wash tax.

As for Summers and the like, they ought to be labeled and cast out for what they are. Ridiculed and dismissed for causing 2008 and the gutting of middle America because their knowledge and work is both wrong and detrimental, perhaps given the meme treatment until it becomes ingrained that their ways are harmful to the extend they can be comedic.

Obviously I tend towards this tactic because of my youth and knowing that academic papers debunking fraudulent theories rarely make a dent in public perception and therefore change in these times.

As the WaPo article pointed out, among the participants on the panel were Bernanke, Rogoff, and Blanchard–all of the high priests of mainstream macro–nodding approvingly to F&S’s conclusion, “Yes, yes, fiscal policy is important, and we are all for more of it! By the way, who’s turn is it for the Nobel?”

I wonder why Kelton wasn’t invited…..?

Jamie is definitely out of the old man’s mold. I remember reading The Affluent Society and The New Industrial State back in the day. He advanced my understanding. Sometime in the early 80’s I listened to him speak about competitive advantage at the Naval War College. In the pre-permanent war days you could actually get on a military base as an ordinary citizen. The old man had an incisive mind and a wicked wit. Give ’em the skewers Jamie…your old man would approve.

Thanks for this.

It would be helpful for Mr. Galbraith to add a few sentences explaining how the Fed sets the Fed Funds rate, rather than just stating that it does.

While most NC readers probably understand the process, it is almost certain that Larry Summers doesn’t.

FWIW the old is always in decay and the new always fighting to be accepted: “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” — Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks

This is some of the more on-the-ball (in terms of economic theory and politically contesting that) stuff that I find most valuable from NC (New Economic Perspectives did a lot of this in the past, too – miss their more regular writing, excellent blog).

The stuff I learn from (even if only to flesh out the details of my understanding) the best, and which makes me value my donations to NC the most.

Hope The Age of Uncertainty makes its way to Netflix some day too, as well :)