By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

Two days before New Year’s, The Wall Street Journal released the following story, “Inside the Google-Facebook Ad Deal at the

Heart of a Price-Fixing Lawsuit,” which I think should have been a blockbuster, but wasn’t, possibly because of the holidays, possiblly because everybody already thinks they’re both crooks. In this brief post, I’ll first extract the key points of the case, and then consider what Google’s actions imply for the idea that we live in a “free market” society.

Before we look at the story, we need to understand a little about how Google ads are sold to buyers. (Naturally, I searched on Google for this, and was greeted with six pages of material from Google itself, interspersed with marketing from SEO firms. Not one academic[1] or journalistic explanation. Good job.) The best description of the algorithm I could find was this (2012) course description from Cornell. From my scan of the marketing literature, the same basic procedure is used today:

The way Google’s auction works is similar to a second price sealed-bid auction. Each time a user searches for a word or phrase, Google saves the data and groups the keywords by relevance. Advertisers associate advertisements with various keywords. Google then matches the keywords from internet users with keywords associated with the advertisements and auctions the advertisement slot to multiple advertisers. The ad rank of each advertisement is calculated based on the maximum bid the advertiser makes for the ad and the quality score. Quality score is a metric determined by multiple components of the advertisement. The product of those is the ad rank. The advertiser with the highest ad rank wins the auction and will have their ad displayed on Google’s website for specific internet users whose search queries match the advertisement’s keywords. However, the price that advertiser pays is not the advertiser’s maximum bid price, rather, it is the minimum amount the advertiser can pay to win the ad auction. In other words, the lowest amount the advertiser can pay to outbid the next highest bid. The price is calculated by the ad rank of the person below the highest bidder divided by the highest bidder’s quality score plus 0.01.

This type of advertisement auction is essentially the second price sealed-bid auction. The auction is a sealed-bid auction because advertisers do not know what other advertisers are bidding.

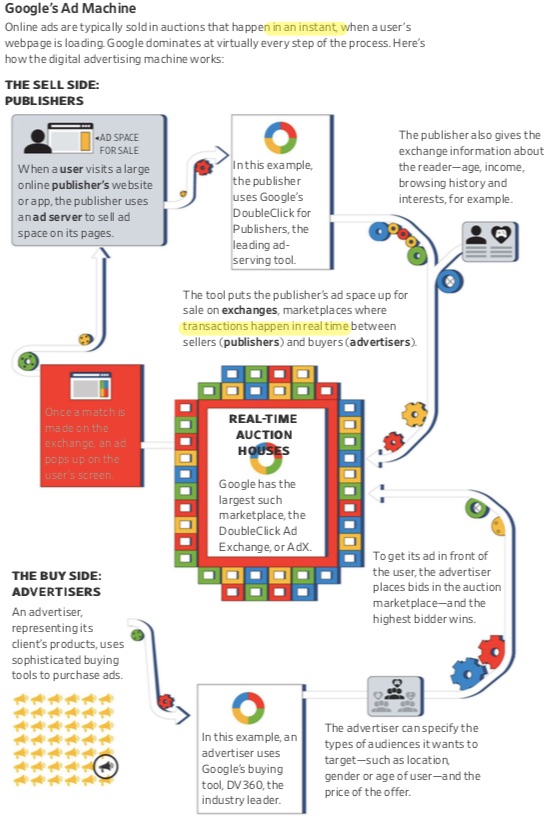

The Journal provides a diagram of all the auction players:

(Note the highlighted “in an instant,” and “transactions happen in real time,” to which we shall return.)

To the story, then, reported by Ryan Tracy and Jeff Horwitz. In an unredacted draft version of the suit obtained by the Journal:

Ten Republican attorneys general, led by Texas’ Ken Paxton, say Google gave Facebook special terms and access to its ad server, a ubiquitous tool for allocating advertising space across the web. This and other conduct by Google, they allege in the final lawsuit, harms competition and deprives “advertisers, publishers and consumers of improved quality, greater transparency, increased output and/or lower prices.”

(Google denies it; Facebook is not mentioned in the suit.) The context in which Google gave Facebook special terms was an effort by publishers to circumvent Google’s online advertising monopoly by dealing directly with advertisers through a technical process called “header bidding,” hopefully cutting themselves better deals.

In March 2017, Facebook publicly endorsed header bidding. Google approached Facebook and in September 2018 reached the digital advertising agreement, the states allege. The draft lawsuit says Google code-named it “Jedi Blue.”

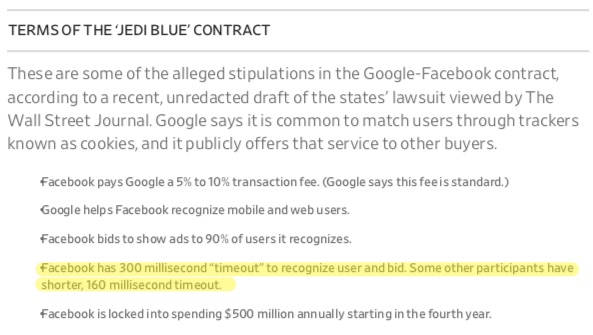

Here are the terms of the Jedi Blue contract:

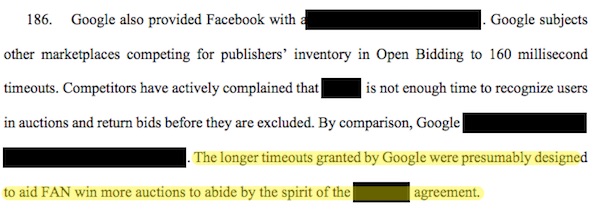

I will focus on the “millisecond” timeout aspect, because while the other terms are such as could be drawn up over cheap steaks and bad red wine in a provincial airport hotel restaurant, the timeout involves and corrupts the inherent technical characteristics of the platform. Oddly, the Journal mentions it, but does not explain it. The heavily redacted original complaint does:

(FAN is “Facebook Audience Network,” presumably feeding the winning bid from Google’s auctions into its own systems.)

Recall the words “in an instant,” and “real time.” As it turns out, Google is gaming its own auction to make those wprds mean different things for different clients. (It’s as if I were buying material at a fabric store by the yard — except the store was using a rubber yardstick, stretching out the “yard” for lucky clients, shrinking it for the unlucky.) Computation takes time. Those extra-milliseconds Google granted Facebook are important, because the auction bidding itself can take milliseconds. The extra time allows Facebook’s systems to be a little bit slower. The extra time also allows Facebook an informational advantage, because — speculating here — it gives Facebook to merge its own data with that it gets from Google. Finally, the extra time allows Facebook to outwait other bidders.

I said that Google’s advertising exchange was using a rubber yardstick. Michael Hudson has something to say about that:

For starters, any practical payment system for credit and trader requires accurate weighing and measuring. This calls for public oversight as a check on fraudulent practice. Trust cannot be left to individuals engaging in barter or credit on their own.

Yet this is exactly what we have done, because Google’s algorithm is proprietary, and Google’s auction is a black box to regulators.

Crooked merchants historically have used light weights [rubber milliseconds] when selling goods or lending out money so as to give their [disfavored, non-Facebook] customers less, and heavy weights when buying or collecting debts so as to gain an unduly large amount of silver or other commodities….

Biblical denunciations of merchants using false weights and measures find their antecedents in Babylonia. Hammurabi’s laws (gap x [Roth 1998:98], sometimes referred to as §94 and §95) stipulates that merchants who lend grain or money by a small weight but demand payment using a larger measure should forfeit whatever they had lent. Ale‑women found guilty of using crooked weights and measures in selling beer were to be cast into the water (§108 [Roth 1998:101])…. Such abuses are timeless. The 7th century BC prophet Amos (8:5ff.) depicts the Lord as denouncing wealthy Israelites “who trample the needy and do away with the poor of the land” by scheming, “skimping the measure (making the ephah small), boosting the price (making the shekel great), and cheating with dishonest scales.” Likewise the prophet Micah (6:11) denounces merchants using “the short ephah, which is accursed? Shall I acquit a man with dishonest scales, with a bag of false weights?” (Kula 1986 reviews Biblical and Koranic examples.)

How is what Google is doing with its 300 millisecond “timeout” for Facebook any different from these “timeless abuses”? Answer, it isn’t. Is this a “free market”? No. If every giant, data-driven Silicon Valley is rigging the game like Google — and why wouldn’t they? — do we even have a “free market society”? No, we don’t.

Hudson also points out the essential role of temples in maintaining weights and measures:

Who else but temples and palaces could have provided honest standards? Monetary exchange could not have been workable without their oversight of standardized weights and measures, attesting to the purity of the monetary metals, and sanctions against fraud. That is why silver was minted in temples from Mesopotamia through Rome. Our word for ‘money’ comes from Rome’s Temple of Juno Moneta…

If there is such a thing as a modern temple, it looks like these:

But our temples are run by crooks who worship an evil God that dotes on fraudsters. I don’t like this timeline at all, and I wish we were all in a different and better one.

NOTES

[1] This, from Nature, is very good. “Because AdWords effects all words, not just copyrighted ones, we have a situation in which all words and ideas online are becoming commodities.”