By Wolf Richter, editor of Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street.

In the major shopping corridors in Manhattan, where sidewalks are lined by ground-floor shops, retail rents have been declining for years – and not just by a little, but by 20%, 30% or even over 40%, amid ballooning vacancies. The brick-and-mortar retail meltdown, Manhattan style. Then came the Pandemic. In the spring during the lockdown, as hospitals and morgues were overwhelmed, the market for street-level retail space froze up. Later in the year, retailers and landlords started making deals again, with “asking rents” falling by as much as 25% year-over-year, and by as much as 55% from the peak in prior years. And “taking rents” – rents actually agreed on – were reported to be even lower.

“These decreases are historic, with 8 corridors experiencing their lowest price per square foot averages in at least a decade,” the Real Estate Board of New York reported in its just released Fall 2020 Manhattan Retail Report. “While asking rents dropped significantly, taking rents are reported to be much lower, with some brokers citing average differences between asking and taking rents around 20%.”

In 11 of the corridors, available retail space further increased, with increases ranging from 6% to 67% compared to a year ago, “which reflects a substantial slowdown in Manhattan retail transaction volume and creates challenges in establishing overarching economic trends,” the REBNY said in the report.

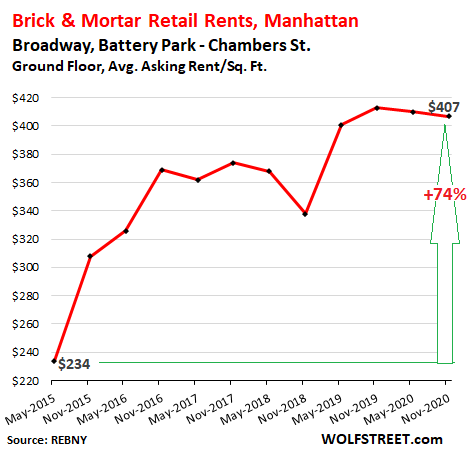

Asking rents in two shopping corridors had bucked the declines through 2019. But in 2020, they also declined: In Downtown, on Broadway between Battery Park and Chambers Street; and in Harlem, on 125th Street, from the Harlem River to the Hudson River.

Midtown

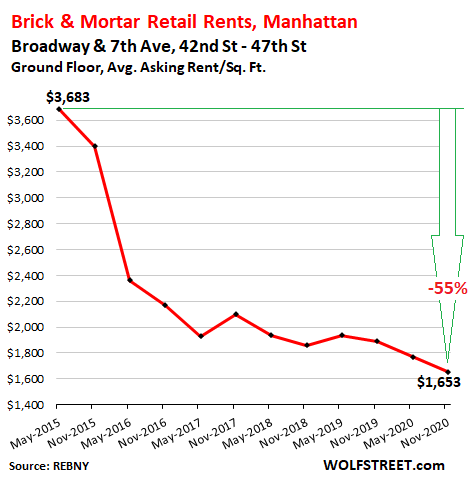

Some of Manhattan’s most expensive shopping corridors are in Midtown. On Broadway and 7th Avenue, between 42nd Street and 47th Street, the average asking rent in the fall of 2020 dropped by 13% from a year ago to $1,653 per square foot per year, having collapsed by 55% from the peak in 2015.

But even after that rent collapse, it’s tough to imagine how a 1,000 square foot retail store, paying a mind-boggling $1.65 million in rent per year, could ever make money. And of course, some of these shops aren’t designed to make money. They’re showcases for expensive fashion brands. But if the fashion brands lose appetite for expensive showcases, what else remains?

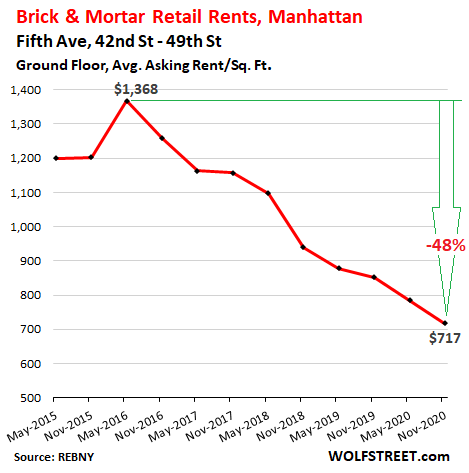

And the two stretches on Fifth Avenue: On the first, from 42nd Street to 49th Street, the average asking rent dropped by 16% year-over-year, and by 48% from the peak in 2016, to $717 per square foot per year, with 15 availabilities in the corridor:

And the two stretches on Fifth Avenue: On the first, from 42nd Street to 49th Street, the average asking rent dropped by 16% year-over-year, and by 48% from the peak in 2016, to $717 per square foot per year, with 15 availabilities in the corridor:

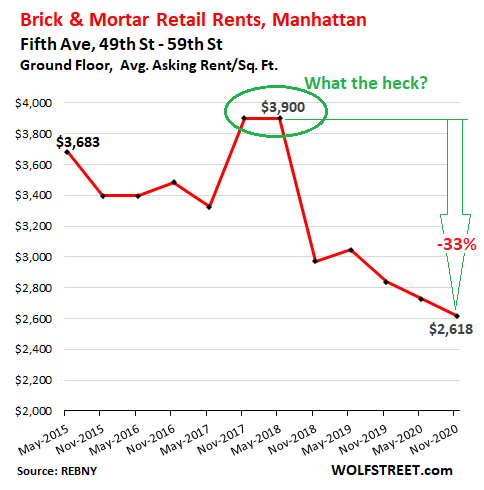

On the second stretch of Fifth Avenue, from 49th St. to 59th St., the average asking rent fell 8% year-over-year to $2,618/sf, and was down 29% from 2015. There were 17 availabilities in the fall of 2020.

But the peak in asking rents was in 2018, when landlords decided, in a what-the-heck moment, to ignore reality and ask for the sky. It didn’t work, retailers didn’t bite, and asking rents reverted to trend. In the fall of 2020, they were down 33% from the illusory peak in 2018:

Midtown South.

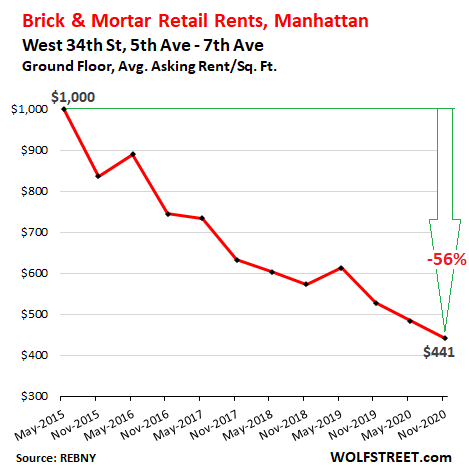

The average asking rent on West 34th Street between Fifth Avenue and Seventh Avenue fell by 16% year-over-year to $441/sf, having now plunged by 56% since 2015:

Upper East Side.

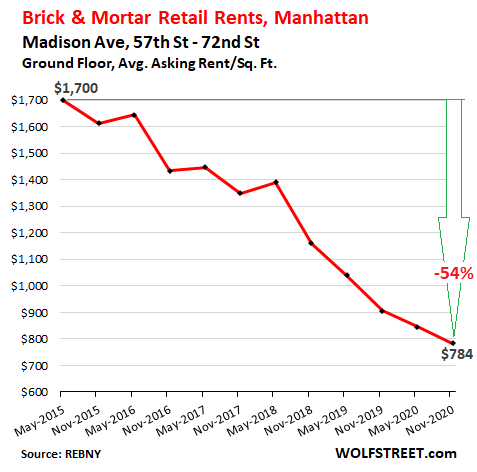

On Madison Avenue, in the shopping corridor between 57th Street and 72nd Street, the average asking rent dropped by 13% year-over-year in the fall of 2020, to $784 per square foot per year, and was down 54% from the first half in 2015, amid 55 availabilities!

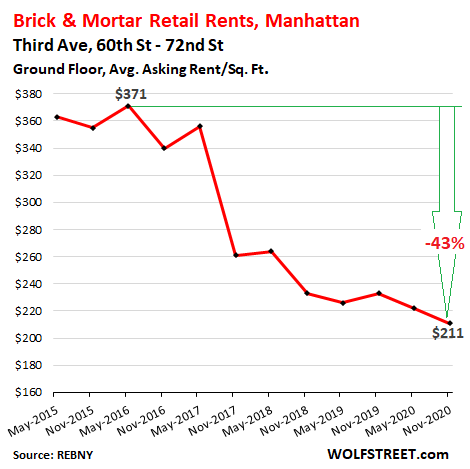

On Third Avenue, between 60th and 72nd Street, the average asking rent fell 9% year-over-year, to $211/sf, and 43% from the peak in 2016:

On Third Avenue, between 60th and 72nd Street, the average asking rent fell 9% year-over-year, to $211/sf, and 43% from the peak in 2016:

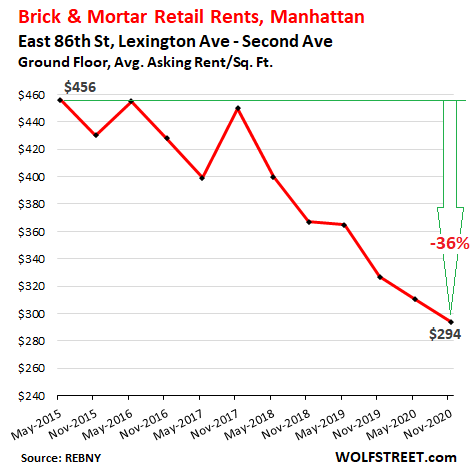

On East 86th Street, between Lexington Avenue and Second Avenue, the average asking rent fell 10% year-over-year and is down 36% since 2015, to $294/sf.

On East 86th Street, between Lexington Avenue and Second Avenue, the average asking rent fell 10% year-over-year and is down 36% since 2015, to $294/sf.

Downtown.

This is an example of just how local real estate can be, and how some spots can defy general trends, until they can’t. Two shopping corridors followed the trends as outlined in the charts above, but another did the opposite.

On Broadway, between Battery Park and Chambers, the average asking rent soared 74% since 2015, instead of plunging, to an all-time high in 2019. But in 2020, it ticked down 1.5% year-over-year:

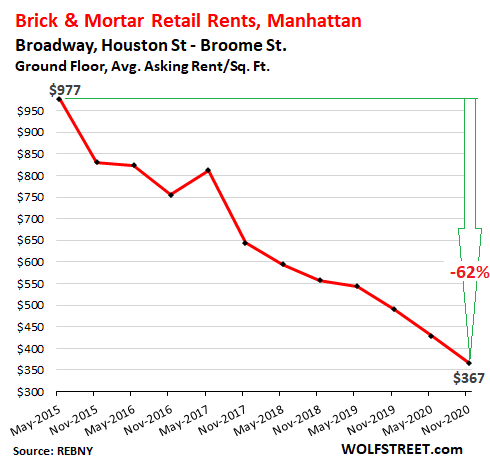

But then, you guessed it, there’s the other extreme; on Broadway between Houston and Broome, the average asking rent plunged by 25% year-over-year and by 62% from the peak in 2015, the biggest decliner in the bunch, amid 26 availabilities:

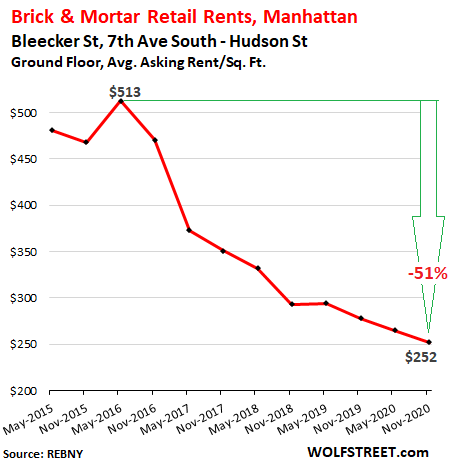

On Bleecker Street, between 7th Avenue and Hudson, the asking rent fell 9% year-over-year and 51% from the peak in 2016, amid 20 availabilities:

On Bleecker Street, between 7th Avenue and Hudson, the asking rent fell 9% year-over-year and 51% from the peak in 2016, amid 20 availabilities:

Upper West Side.

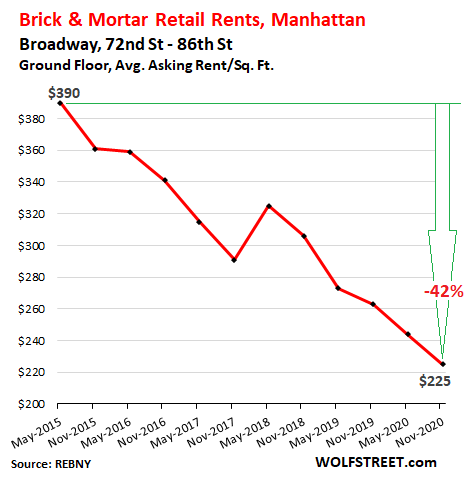

On Broadway between 72nd Street and 86th Street, the average asking rent fell 14% year-over-year and is down 42% from 2015. There were 27 availabilities:

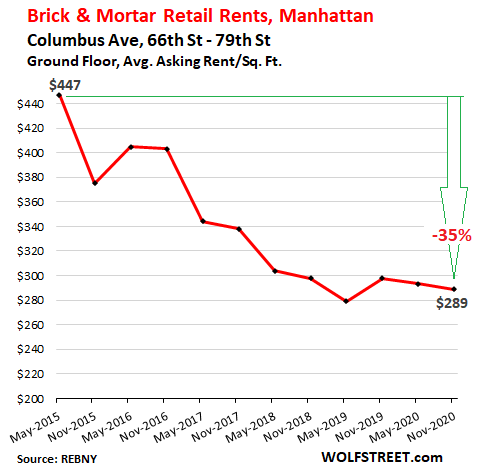

And on Columbus Ave, between 66th Street and 79th Street, the average asking rent declined 3% year-over-year and was down 35% from the peak in 2015:

Upper Manhattan.

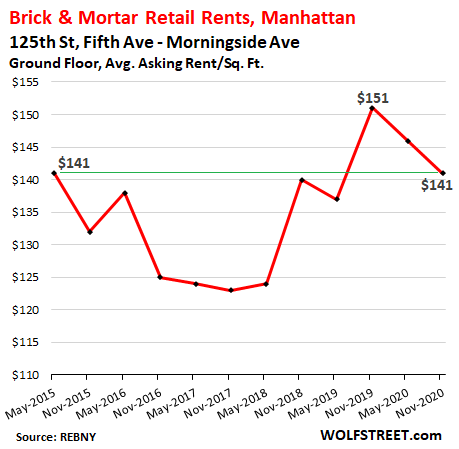

Another exception through 2019, the shopping corridor on 125th Street in Harlem, from 5th Ave to Morningside Ave: the average asking rent started rising in 2017 and hit a new high in 2019. But in the second half of 2020, it fell 7% year-over-year, and was right back where it had been in 2015:

In theory, drastically lower rents would attract more interest from retailers. But the brick-and-mortar retail model is broken. Ecommerce rules. Even luxury retailers have figured out during the Pandemic how to sell their merchandise online. While grocery stores, along with bodegas in the neighborhood for last-minute purchases, and some other services-focused enterprises, such as barbershops, hair salons, and nail salons, are seen as essential by many consumers, much of the rest of retail can be and has been shifted to ecommerce. Cafes and restaurants can replace retail stores, but at some point, the street is going to be saturated with cafes and restaurants.

And when rents are too high, even though they may be a lot lower than they used to be, none of these enterprises can turn a profit. As in so many cases, the Pandemic just pushed the existing trends in Manhattan’s retail property scene to the next level.

Wondering what the more systematic effects of this could be in major cities. The predominant argument I still hear is that once the pandemic is corralled the world will return to the prior normal. This, of course, ignores the history of nearly all past pandemics when a new normal is established.

As a life-long New Yorker that spent major portions of my career working in mid-town, much of the retail is part of the life-work ecosystem. If I couldn’t run out at lunch to do some quick, but necessary, shopping the entire value proposition of locating mass employment in central business districts drops materially.

Working in most major cities, globally, imposes a huge time cost in transit times. If one can no longer perform certain basic functions integrated into the work day I suspect it will cause major pushback. And while I acknowledge that e-commerce substitutes for a part of what is lost, at the margin its not the same convenience.

My friends in real estate also tell me that when they sell a corporate client on office space they also sell the building and neighborhood. If the neighborhood is largely vacant store fronts — yuck.

As a rough rule of thumb, I only partially joke that Sam Zell is always right. Zell thinks Manhattan office real estate will come back, and that if you buy at below replacement rate you will probably be fine. However, how much of this stuff is trading below replacement rate?

Another good question is what are the longer term effects of falling rents? I have a sneaking suspicion that the main effect is purely distributive and if there is an macro effect it is effectively positive. Falling rents will make a city stronger because less of product of commerce needs to go to the parasitic landlord class. I suppose there must be large wealth/distributive effects because much of these rents have been securitized. So I would imagine the ultimate transfer is from pensions (which will be less solvent at the margins) and billionaires, to young(er) business owners.

What do others think?

I don’t think the office is dead, but I do think that offices will fundamentally change.

A few years back I was at a seminar on urban development and a developer was asked ‘what are the big IT companies looking for?’ He said ‘three things: floorplate, floorplate, and floorplate’. In other words, they wanted big open offices that provided them with flexibility and staff surveillance. I think that market will suffer the worst.

I think offices will start to resemble the offices of 100 years ago. Smaller, with an emphasis on prestige buildings and prestige locations, with lots of private offices as a perk for staff. I think we’ll see a three way split – senior staff still wanting their HQ office with key staff in the office around them. A mid layer of floating staff, working between home and hot desking elsewhere (maybe in cheaper local offices? Its hard to know). And a bigger army of freelancers around the world, doing lots of the easy drudge work in cheap locations. And not just drudge work – a friend who works as a co-ordinator for a major translation company just moved to a little village in Portugal. Its super cheap and she loves it there.

This, of course, is just a guess based on what I’m hearing from people in a variety of sectors. A major complication could be local tax laws – for example, here in Ireland companies that sent their staff to work from home found that ‘home’ was often Germany or Italy. Which was fine, until someone found out that this had serious (negative) tax implications for the companies if their staff turned out not to be resident in Ireland. So they insisted to staff that they had to find somewhere in Ireland to live for at least a month last year. I’m sure there are lots of little problems like this will emerge as things formalise.

As for retail, I’m not sure the change will be as radical elsewhere as it is in Manhattan, which is something of an extreme case. Retail has been changing radically for years, but there is still a demand for all sorts of different types of local shops and services. With luck, it will be the big malls and drive in retail sheds that get hit hardest, while more traditional Main Streets can take advantage of lower rents to find new uses. To take one advantage, the boom in smartphones led to a major increase in prime retail rents as the phone companies were willing to accept high rents as a loss leader to become more visible to consumers. Even before Covid, they were reversing this policy so that this provides more scope for other uses to move in as rental pressure relaxes. Unfortunately, commercial rents tend to be sticky on the downside so it can take time for this to happen.

Fascinating and a very plausible scenario. One observation. For my sins I now live in a North East suburb. So I am increasingly familiar the the very tedious malls which make up a lot of the retail capacity in the US suburbs. Turns out they have been subject to repurposing too. Now, you take you kids to the mall to have them jump around trampoline parks, or wall climbing facilities, or even enormous cross-fit gyms. I don’t know how much less valuable such space is, but it does a fine job at anchoring space. It costs about $10 to exercise the toddlers for 30 mins in a trampoline facility like Skyzone. Probably better than administering tranquilizers.

to me the bounceback will take a while….the bread and butter of non-Midtown districts like Soho aren’t international tourists but weekend regional and suburban visitors.

many of those visits are permanently gone whether cuz of online shopping, populace decline-stagnation in the Northeast, crime (regardless of whether the perception is fair), people have found other things to do.

and like you said, any district needs a critical mass

Prices are “sticky” because those who’s income relies on the old price have fixed obligations at that price.

The commercial collapse will thus take time to ripple through the regional economy. For instance, my Brooklyn lease is up in March and my landlord still has delusions of last years prices along with a lifestyle built around them. I’ve asked him to have the two realtors he likes look at the apartment and tell him what they think its worth: a year ago there were 20 zillow listings in my neighborhood, today its approaching 300.

Urban living, up to 8-12 stories, will be more efficient again when the prices are right. It will take a while.

I wonder what is happening in the outer boroughs? For example, Fordham Rd in the Bronx.

From what I saw they are less affected. 1) Rents are much lower 2) Ordinary people who tend to live in these areas, are more frequently “essential workers” and have been forced to keep working. So they continue to use local businesses.

I live in Manhattan, where tourist-oriented neighborhoods – Midtown, Greenwich Village, Soho – are bleak and empty. Sidewalk dining has not been able to make up for the large decline in foot traffic, and my neighborhood, the West Village, is silent late at night, with virtually no commercial traffic or street life.

My daughters live in the Bronx and Queens, where life goes on a bit more closer to normal. However, with the city’s tax base so dependent on commercial real estate, it’s hard not to see the problems extending outward from the commercial core. The city’s once mighty commercial tax base subsidizes rates on single and two-family homes, which can be 80% less than the surrounding suburbs; I have a friend who pays $4,000 per year for a four-bedroom, single family home in a desirable part of the Bronx. The city is going to be desperate for cash, and it’s hard to see those low rates being maintained for long.

Wasn’t Greenwich Village once an inexpensive place that attracted the bohemian artist types?

Perhaps history is repeating.

Having had the joyous experience of living in the Village from Sep 59 to July 68, I can only report that it was the only place to live.

I actually started out in a 7 room apartment on the 14th floor on the north side of Gramercy Park. “I knew folks,” as the saying went.

I soon had to move to 3rd and East 21st (or as I described it, “just off Gramercy Park”) in a 5th floor rent controlled walkup, moving to a one room unit in Ellinger’s Warehouse on Hudson Street, and then to the subsidized units built by NYU just south of Washington Square from which I watched the World Trade Center going up. It was where I watched the blackout that started in Niagara Falls.

The Village was the most exciting place that I have ever lived. Jane Jacobs stopped Robert Moses, there were great bars and restaurants, McSorley’s existed. Leaving was a career move, but as I learned, nostalgia soon arose and I’ve never recovered.

That was a long time ago. With the exception of rent-stabilized old-timers, the neighborhood has become an increasingly transient “home” to centi-millionaires and platinum blonde sorority sisters.

My father’s childhood coincided with the first, pre-WWI Village bohemia, that of John Sloan, John Reed, Carlo Tresca, Eugene O’Neill and the Mabel Dodge salon, et. al.. When I was a kid growing up in the neighborhood during the 1960’s, he used to bitterly say across the dinner table, “Ah, you’ll never know the real Village, Michael: the SOBs destroyed it in the ’20’s.”

Everybody loses their New York.

Without knowing the neighborhoods it’s hard for me to know what to make of the differences between these graphs. For example, do the upswings in Downtown and Upper Manhattan reflect those neighborhoods becoming more fashionable?

And removing those two there’s a general 5-yeard downward trend. What does that reflect? Were residential rents doing the same? Is that to do with ecommerce too? idk…

I work down there and it makes no sense.

That’s where Century 21 just went bust.

My only thought is that it has to do with leasing out Calatrava’s transit center super high end mall, across the street from the corpse of C21.

This, obviously, is only a supposition dependent on the thing I’m getting with individuals in an assortment of areas. A significant difficulty could be neighborhood charge laws – for instance, here in Ireland organizations that sent their staff to telecommute found that ‘house’ was frequently Germany or Italy. Which was fine, until somebody discovered that this had genuine (negative) charge suggestions for the organizations if their staff turned out not to be inhabitant in Ireland. Best jigsaw popular mechanics So they demanded to staff that they needed to discover some place in Ireland to live for at any rate a month a year ago. I’m certain there are heaps of little issues like this will arise as things formalize.

I ventured to the Big Apple for a week every December from 1978 to the mid 80’s, when it was especially maggoty. As far as I can tell, the only thing that stopped it from being Cleveland, was the machinations performed in Dow Jonestown since.

Being from L.A. which was a pretty nice place and the smog was going away on account of catalytic converters, it seemed like the biggest dump to me, but attractive in its own way, the squalidness of Times Square, carcasses of cars parked along the street, nothing left of value-stripped bare. It had life though, something missing in the City of Angles.

I always anticipated my visits there, but 1/52th of a year was plenty.

For decades, Cleveland has attracted refugees from NYC. In the age of Covid, they continue to straggle in … ;-)

The collapse of rents is exactly what you would predict at this point in a secular cycle. See Turchin and Nefedov.