Yves here. This post by Daniel Nettle, and his underlying paper, focuses on the how desperation drives behavior in societies with high levels of inequality. Critically, Nettle focuses on a key implication of significant inequality: if your economic status slips, it completely upends your life. You can’t afford to send your kids to private school, tutors, and fancy summer camps. Or you have to give up the second home. Or the club memberships. Or the charities and the business opportunities that go with them. Or the dinners out. Or all of the above and move into a smaller home in a different area. In other words, if you fall from your perch, it forces you to rebuild most of your friendships (which shows how shallow friendships are in America, yet another facet of high inequality). So the incentives to preserve you status are high, which can lead to criminal conduct.

When inequality was lower that it is now, I had a journalist friend (wrote regularly for Vanity Fair, so she would be considered very successful) who had gone to an Ivy. Her friends consisted of women who were mainly in finance or law firms and were oblivious to the implications of the income gap. They’d ask her to go out with them for dinner at places that were budget-breakers for her and put her in the embarrassing position of having to make up an excuse as to why she could join only for a drink.

By Daniel Nettle, Professor of Behavioural Science at Newcastle University. His varied research career has spanned a number of topics, from the behaviour of starlings to the origins of social inequality in human societies. His research is highly interdisciplinary and sits at the boundaries of the social, psychological and biological sciences. Originally published at Daniel Nettle’s website; cross posted from Evonomics

Societies with higher levels of inequality have more crime, and lower levels of social trust. That’s quite a hard thing to explain: how could the distribution of wealth (which is a population-level thing) change decisions and attitudes made in the heads of individuals, like whether to offend? After all, most individuals don’t know what the population-level distribution of wealth is, only how much they have got, perhaps compared to a few others around them. Much of the extra crime in high-inequality societies is committed by people at the bottom end of the socioeconomic distribution, so clearly individual-level of resources might have something to do with the decision; but that is not so for trust: the low trust of high-inequality societies extends to everyone, rich and poor alike.

In a new paper, Benoit de Courson and I attempt to provide a simple general model of why inequality might produce high crime and low trust. (By the way, it’s Benoit’s first paper, so congratulations to him.) It’s a model in the rational-choice tradition: it assumes that when people offend (we are thinking about property crime here), they are not generally doing so out of psychopathology or error. They do so because they are trying their best to achieve their goals given their circumstances.

So what are their goals? In the model, we assume people want to maximise their level of resources in the very long term. But-and it’s a critical but- we assume that there is a ‘desperation threshold’: a level of resources below which it is disastrous to drop. The idea comes from classic models of foraging: there’s a level of food intake you have to achieve or, if you are a small bird, you starve to death. We are not thinking of the threshold as literal starvation. Rather, it’s the level of resources below which it becomes desperately hard to participate in your social group any more, below which you become destitute. If you get close to this zone, you need to get out, and immediately.

In the world of the model, there are three things you can do: work alone, which is unprofitable but safe; cooperate with others, which is profitable just as long as they do likewise; or steal, which is great if you get away with it but really bad if you get caught (we assume there are big punishments for people caught stealing). Now, which of these is the best thing to do?

The answer turns out to be: it depends. If your current resources are above the threshold, then, under the assumptions we make, it is not worth stealing. Instead, you should cooperate as long as you judge that the others around you are likely to do so too, and just work alone otherwise. If your resources are around or below the threshold, however, then, under our assumptions, you should pretty much always steal. Even if it makes you worse off on average.

This is a pretty remarkable result: why would it be so? The important thing to appreciate is that with our threshold, we have introduced a sharp non-linearity in the fitness function, or utility function, that is assumed to be driving decisions. Once you fall down below that threshold, your prospects are really dramatically worse, and you need to get back up immediately. This makes stealing a worthwhile risk. If it happens to succeed, it’s the only action with a big enough quick win to leap you back over the threshold in one bound. If, as is likely, it fails, you are scarcely worse off in the long run: your prospects were dire anyway, and they can’t get much direr. So the riskiness of stealing – it sometimes you gives you a big positive outcome and sometimes a big negative one – becomes a thing you should seek rather than avoid.

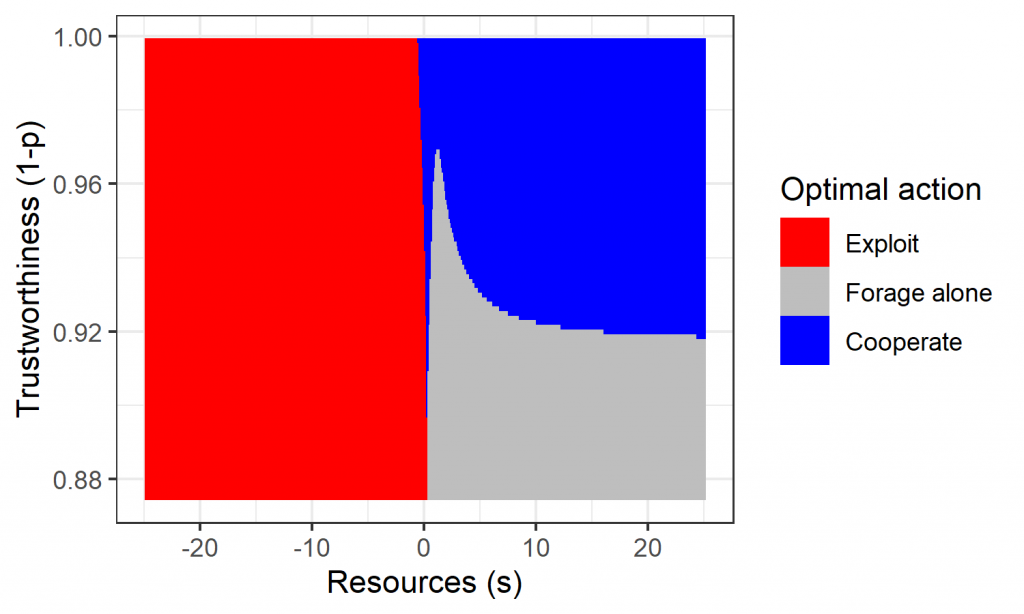

So, in summary, the optimal action to choose is as shown in figure 1. If you are doing ok, then your job is to figure out how trustworthy your fellow citizens are (how likely to cooperate): you should cooperate if they are trustworthy enough, and hunker down alone otherwise. If you are desperate, you basically have no better option than to steal.

Now then, we seem to be a long way from inequality, which is where we started. What is it about unequal populations that generates crime? Inequality is basically the spread of the distribution of resources: where inequality is high, the spread is wide. A wide spread pretty much guarantees that at least some individuals will find themselves down below the threshold at least some of the time; and figure 1 shows what we expect them to do. If the spread is narrower, then fewer people hit the threshold, and fewer people have incentives to start offending. Thus, the inequality of the resource distribution ends up determining the occurrence of stealing, even though no agent in this model ‘knows’ what that distribution looks like: each individuals only knows resources what they have, and how other individuals behaved in recent interactions.

What about trust? We assume that individuals build up trust through interacting cooperatively with others and finding that it goes ok. In low-inequality populations, where no-one is desperate and hence no-one starts offending, individuals rapidly learn that others can be trusted, everyone starts to cooperate, and all are better off over time. In high-inequality populations, the desperate are forced to steal, and the well-off are forced not to cooperate for fear of being victimized. One of the main results of Benoit’s model is that in high-inequality populations, only a few individuals actually ever steal, but still this behaviour dominates the population-level outcome, since all the would-be cooperators soon switch to distrusting solitude. It is a world of gated communities.

Another interesting feature is that making punishments more severe has almost no effect at all on the results shown in figure 1. If you are below the threshold, you should steal even if the punishment is arbitrarily large. Why? Because of the non-linearity of the utility function: if your act succeeds, your prospects are suddenly massively better, and if it fails, there is scarcely any worse off that it is possible to be. This result could be important. Criminologists and economists have worried why it is that making sentences tougher does not seem to deter offending in the way it feels intuitively like it ought. This is potentially an answer. When you have basically nothing left to lose, it really does not matter how much people take off you.

In fact, our analyses suggest some conditions under which making sentences tougher would actually be counterproductive. Mild punishments disincentivize at the margin. Severe sentences can make individuals so much worse off that there may be no feasible legitimate way for them to ever regain the happy zone above the threshold. By imposing a really big cost on them through a huge punishment, you may be committing them to a life where the only recourse is ever more desperate attempts to leapfrog themselves back to safety via illegitimate means.

So if making sentences tougher does not solve the problems of crime in high-inequality populations, according to the model, is there anything that does? Well, yes: and readers of this blog may not be surprised to hear me mention it. Redistribution. If people who are facing desperation can expect their fortunes to improve by other means, such as redistributive action, then they don’t need to employ such desperate means as stealing. They will get back up there anyway. Our model shows that a shuffling of resources so that the worst off are lifted up and the top end is brought down can dramatically reduce stealing, and hence increase trust. (In an early version of this work, we simulated the effects of a scenario we named ‘Corbyn victory’: remember then?).

The idea of a desperation threshold does not seem too implausible, but it is a key assumption of our model, on which all the results depend. Our next step is to try to build experimental worlds in which such a threshold is present – it is not a feature of typical behavioural-economic games – and see if people really do respond as predicted by the model.

De Courson, B., Nettle, D. Why do inequality and deprivation produce high crime and low trust?. Scientific Reports 11, 1937 (2021).

Inequality is kind of a Genocide as well. We see this in California created by Public Employee Unions, which have created a SuperClass that controls who wins elections (along with George Soros) and have created a perpetual one-party state. Economically, that one-party can pass almost any legislation favoring these Unions (SB400) and the Unions can initiate almost any type of fee or tax they wish. The proceeds of the taxes and fees many times go to the General Fund and from there to backfilling CALPERS and CALSTRS. However, the populace is getting increasingly smart and now questions these endless appeals such as “For the Children”. They convinced the taxpayers to pass a gas tax (highest in the nation) to do road improvements. I have yet to see any. I do see a higher number of street lights out and unfixed potholes as my city is burdened with huge increases in CALPERS Pension contributions. My local water district is over 40 million in arrears in CALPERS contributions and deathly afraid to raise their obscenely high water rates to cover it. Meanwhile, over 80,000 CALPERS retirees have pensions over 100k,with the top winner, Curtis Ishii, getting over $418,600 per year. This is government sponsored Socialism, Genocide and Inequality all in one.

I’ll leave it to other, wiser commenters to address the numerous inadaquacies of this comment. But my mother, who was a long time, poorly paid Los Angeles teacher and now is suffering from Alzheimer’s, is able to survive thanks to her CALSTRS pension and LTC plan. (I literally made more money per year than she did in my first year of full time computer programming work back in the early 80’s.). If that makes you upset, so be it.

People like Stan Sexton are a huge part of the problem. With people like Stan, it is ALWAYS a Union’s fault–for everything. The Unions give people like Stan the chance to deceive everybody as to who the REAL culprits are for the way the world is now. The folks who have lots of money–NONE of them Union members–have shaped the Political System of today. Statewide and Nation wide. Stan and his type are oblivious to this–or maybe not? Maybe Stan is trying to fool all of us? Stan is a puppet–willing or not willing–of the wealthy elites.

You’re falling prey to the notion that government is not there to help people, but rather to facilitate the grift of connected insiders. I see it as a success that people who fulfilled their part of the bargain are now reaping the amortized benefits… you work for x , we’ll give you y later. Which is a gamble of course because no one knows when they will perish. And related to my comment below CalPERS specifically is the golden calf in the no trust environment fostered by the response to the great recession with the rule of the pile of money being someone wants to steal it and since they got away with it last time and who cares about a bunch of rubes who made a deal in a no trust environment where of course the pensioners should lose their pension… Comments of this nature also make me wonder what the posters feelings about insurance are? Pensions and SS are basically insurance policies, but here we go again where is trust in the community of insurance? Apparently I could go on and on here..

The facts:

Kochs’ spending in 2016: $889 million.

Soros’ spending in 2016: $20.6 million

Kochs are such hard righties that they were literally raised by a Nazi (their nanny was a member of Hitler’s party)

Soros is a capitalists capitalist who made his bones speculating in currency. Commodity1 -> Money ->Commodity2 is a market. Money1 -> Commodity ->Money2 is a capitalist market. Soros’ thing is Money1-> Money2 ->Money3.

Saying the political left, or labor is even moderately influential is a distortion. Labor, even in “left coast” California, is weak tea compared to the billionaires.

Here’s a quote I found thanks to NC that describes this as perfectly as possible:

why 70 million votes for Trump? Says Thomas Greene (from Noteworthy): “Trump will not be defeated by educating voters, by exposing his many foibles and inadequacies. Highlighting what’s wrong with him is futile; his supporters didn’t elect him because they mistook him for a competent administrator or a decent man. They’re angry, not stupid. Trump is an agent of disruption — indeed, of revenge…..Workers now sense that economic justice — a condition in which labor and capital recognize and value each other — is permanently out of reach; the class war is over and it was an absolute rout: insatiable parasites control everything now, and even drain us gratuitously, as if exacting reparations for the money and effort they spent taming us. The economy itself, and the institutions protecting it, must be attacked, and actually crippled, to get the attention of the smug patricians in charge. Two decades of appealing to justice, proportion, and common decency have yielded nothing.”

Wow, opposed to good Middle Class American jobs with pensions. Opposed to the working stiff that busts thier butt for thirty – forty years so that they can retire.

Good to know.

Honestly, I didn’t vote for Trump (and I didn’t vote for Biden), but I thought Making American Great Again is a pretty good idea and that means good middle class American jobs with a pension are a good thing. Thant’s part of what made America great. We need more of them, not less.

Ah yes, let us call everything we hate Genocide and Socialism. For gods sake, how can it be ‘genocide’ if nobody is being murdered as a result? Clearly the great genocide caused by Public Employee Unions and CALPERS will go down in the history books with 0 people violently killed…

This is one of the most ignorant comments I have ever read.

Venture capitalists have spend over $14 billion in losses at Uber to help create a precariat class. Private equity buys companies, routinely cutting workforces and often loading them up with so much debt that they wind up in bankruptcy, yet they still profit due to their fee structures….and you are mad at government workers who make less in a year than the heads of PE firms who make 12 times as much IN A DAY than even very well paid CA state employees make in a year?

You have zero idea who or what the real problem is.

Stan, you are so wrong on so many levels it seems you have fully imbibed the neoliberal koolaid. Its actually socialism for the rich and powerful and raw capitalism for the rest, with the elites bamboozling many of the rest to blame their fellow non-elites. Proposition 13 moved taxes from property (held more by the elite) to incomes, and Prop 22 will help turn all workers into the equivalent of farmworkers waiting by the roadside to see if they have work today. Uber and Lyft etc. only exist because the California elite allowed them to break the law with impunity.

I’m not sure the issues of crime and trust can be linked together even if the answer is the same. Seeing as I’m poor / non-white I can easily explain why inequality produces crime. Living in poor economic areas means there isn’t a lot of external investment and economic development in those neighborhoods.The only consistent capital flowing into these areas is derived from the narcotics trade. Of course, this causes all kinds of socioeconomic issues and pathologies that aren’t easily addressed through politics or social programs.

Different areas of socioeconomic status are plagued by various levels of crime. For instance, I don’t have to worry about petty crime in my poor neighborhood. Why? Because the dealers won’t sell to those people. It’d otherwise cause them too much trouble and scrutiny. Even though the individuals around town doing small criminal acts (ie; petty theft) are definitively some of the same people buying drugs from them. Although my chances of being a victim of a random act of violence is probably higher.

I don’t think I have to explain why the drug trade intensifies violent crime.

petty crime is almost nonexistent because you know that your neighbors, like yourself, have nothing worth stealing.

Uhh, value is relative in this specific case. Particularly when the price of heroin is near an all time low. I imagine it’s one of the fringe benefits or incurred social costs of the war in Afghanistan.

i speak from the vantage of growing up in an actual poor person urban “ghetto”. not of your supposed “moral drug dealer” viewpoint (although, as a person who grew up in a series of drug dealing households, they do have rules about who is not to become a customer, amounting to “don’t sh*t where you eat”).

is there crime? sure is. but not of the variety that most people worry about–car and housebreaking, stealing stuff from your yard and holding you up for your wallet. that is the crime that middle class and upper class worries about, and thinks they will be subject to if they go through the bad parts of town.

I wasn’t making a justification or moral case for it anyhow. I view it all as the primitive accumulation of a decaying society.

When I first started managing rental property in East Oakland I was puzzled by the people who acted as though they had no stake in Society.

Oh.

They don’t, and since Society has made it brutally clear that there is no place for them, or their children, the response is rational.

The best estimate of how many Americans will become newly homeless this year comes from Wolf Richter, who estimates it will be @ 1 Million…

I will also note that this model doesn’t mention Wells Fargo, Deutsche Bank, CITI, etc, criminal behavior by the elites is and has been rewarded extravagently in the USA for some time…

“Her friends consisted of women who were mainly in finance or law firms and were oblivious to the implications of the income gap.”

I may as well point out that being in Law isn’t quite what it used to be anymore. There’s a huge overabundance of law school graduates now, leading to underemployment or even unemployment (in Law related jobs) for many Law school graduates. The US apparently produces three times as many law school graduates per capita than most other first world countries (I can’t remember where I read that, but I can at least link a Twitter comment with a graph where US has one of the biggest percent of employed lawyers per capita, with three times that of Germany and a full five times more than France, because of how over-litigated America has become).

Law just isn’t the ticket to the upper middle class and steady employment that it used to be. I think there was a scandal awhile back where several smaller law schools were employing their own graduates for six months so they could claim higher rates of law employment for their graduates during the sixth months after their graduation. Part of the reason Law schools are so popular and profitable is due to advertising and everyone thinking its a path to good incomes when getting law jobs is essentially more competitive here than it has been in the past. I suppose its one of the many fields that have become crappified over the years. Also law school is hideously expensive, so going to Law school with student loans and not being able to have proper employment afterwards is even more of a problem for persons who go to law school compared to graduate from regular colleges, especially since Law school requires a college bachelors degree to get in.

Even formerly posh sectors like Law are becoming more and more precarious. Probably is a thing basically everywhere in this economy. People just don’t notice. What Law school graduate, or other educated professional, wants to admit on facebook that they aren’t able to find proper employment in their field?

To be fair, that woman’s friends were Ivy League lawyers, so they probably have the cushiest incomes and positions at major firms.

https://twitter.com/PankajGhemawat/status/575654688491708416

Happened already with software development, with increasingly offshored staff and H1Bs. Saw the same in financial back offices as well. In addition, I have seen so many service firms outsource their customer presentations and low-level work to India etc., removing many of the entry level positions. The offshoring and crapification of jobs is working its way up slowly though the upper middle class. COVID helped give it an extra push, showing how remote workers can be utilized even more.

Universities are in the business of making money and expanding so that the administrators can get paid more, not for the benefit of the students. Also, the information loop from the reality of work opportunities is very slow, with the universities working as hard as possible to hide it from the starry eyed youth. Just look at the ridiculous number of PhDs being produced in relation to society’s requirements for them. Most plumbers and electricians will probably end up making more than most PhD grads (especially in the social sciences).

There is a theory that part of the Idpol wars etc. is all the grads/post-grads attempting to hold their status above the educationally unwashed, as they have little or no income differential to do so. Like the PhD barista with the bad attitude to the “deplorable”. Just to note that I am a PhD candidate in the social sciences (after retirement) before anyone accuses me of being a pissy deplorable.

I think we should play the what if game

What if a certain percentage of the population can change the definition of words and their meanings e.g., crime? So what would normally be a crime becomes acceptable or not only acceptable but expected with the possibility of punishment virtually non-existent.

What if a certain percentage of the population can change which laws are enforced, how they are enforced and the punishments? e.g., create punishments which create profit centers for those same populations; create crisis which only they know how to fix; create…

What if a certain percentage of the population really only cares about minimizing their own probability of being on the receiving end of random acts of violence? Or minimizing what is acceptable to do to their own ingroup?

What if the point of creating laws isn’t about minimizing crime so much as it is about maintaining hierarchy i.e. maintaining the tacit as well as written rules of The Machine?

What if we focused our attention on the top instead of the bottom when looking at these issues?

Ordinary people wouldn’t have any respect for their betters if they understood that. The President of the United States is usually the world’s largest arms dealer every year. Considering the quality of some of those arms one could be forgiven for viewing it as a form of protection money. The amount of drug money laundered through Wall Street and regularly “taxed” is merely the cost of doing business. The examples are practically endless.

Personally, it’s why I view international relations, particularly between countries, as mostly just uppity gangsterism. The mask really falls off during moments in history like the Opium Wars.

It’s well understood that societies with high levels of inequality have (among other things) high levels of crime, although nobody is really quite sure why. This article doesn’t help, because it doesn’t really define either “crime” (which it seems to conflate with stealing) or “trust”. Countries with very high levels of inequality (the US, South Africa) have very high levels of all kinds of crime, especially violent crime, generally without an economic motive. And there’s no evidence to suggest that being poor, of itself, makes you more likely to steal. Indeed, the article ignores the fact that most crime today is organised in some form, and mostly directly or indirectly related to drugs and other forms of trafficking. Where the article is half-right is that if, say, you are a functionally-illiterate teenager from a broken immigrant family in one of the rougher French suburbs, then your career horizons are very limited, and you’re likely to seek an entry-level position with the caid of a local drug cartel for want of anything better.

But why does this happen, and why in some cases but not others? In spite of what is hinted in the article, criminologists have in fact done a lot of work on the subject. It’s long been known that tougher sentences as such don’t deter crime (except among fairly sophisticated professional criminals) but certainty of being caught and convicted does. However, that has relatively little to do with law enforcement; it’s overwhelmingly to do with public support and trust in the police and the judicial system. In most countries, well over 90% of convictions are as a result of public involvement. For that, you not only need trust in the criminal justice system, you also need community solidarity which means you put yourself out in the interests of others. And of course it’s informal social pressures and controls, well before laws and police, that determine the level of criminality in the first place, which is why crime tends to be lower in communities with high social capital, even if they are very poor. Inequality (which often amounts to the wealthy stealing from the poor anyway) breaks down this capital, and produces social behaviour (the classic example is one-parent families with absent fathers) that is statistically correlated with higher crime rates.

Finally, of course, much crime isn’t about the rich stealing from the poor. The poor are often the main victims, because crime is easier. The elderly couple running the corner shop are such more likely to have to pay protection money to the local gang boss than the well-off owner of a Mercedes franchise. Unless you understand the extent to which (usually organised) crime is a parasitic economic ecosystem rather than a series of rational economic decisions by individuals, you haven’t understood much.

>>>Unless you understand the extent to which (usually organised) crime is a parasitic economic ecosystem rather than a series of rational economic decisions by individuals, you haven’t understood much.

Like much of our government? In cities like Los Angeles, Chicago, Detroit, New York, Baltimore, Camden, and New Orleans policing for personal profit particularly among the narcotics, gang, and gun control units or task forces seems normal behavior; the actions includes home invasion, armed robbery, theft, blackmail, framing, perjury, and murder. In many more cities and counties, it is policing for governmental profit; creating and increasing penalties as a form of taxation and this usually includes civil asset forfeiture were the victims often are never even charged with a crime. Cities like Tucson, Ferguson and Philadelphia are good examples. The more money is needed the more crime is “found” and the higher the monetary punishments are.

This means that the community, usually Black or Hispanic, but often White, and almost always poor or working class consider the police an armed gang not to be trusted or used. Please note that this process is separate from any kind of racism although that can make things much worse.

In extremely poor areas the drug trade is often the main employer even if it only pays the minimum wage for the retail street dealers. It’s just like McDonald’s only with out the guns. Gangs are also a form of protection. Often the only dependable one in particular poor areas with very corrupt governments, which is describing growing areas of America.

Also, violence is a sign of dysfunction. Neither the gangs, police, community, or government wants violence especially murder. Not only is it bad for business it also means having your coworkers, friends, neighbors, and family being in danger. That is why having violence interrupters like former gang members or task forces of community organizers, police, and government officials talk with the leaders of the gangs can drop violence down greatly; it’s we can some sodas, pizzas and gift cards with regular meetings to chat and find ways we can help and no shootings. The first gang that breaks the truce gets our full attention. It sometimes comes to where the gangs themselves will complain to the cops when someone starts shooting. Nobody wants people to die and if it means some drug dealing is ignored by the police or deliberately involving the police in gang violence people are usually fine with it. If it keeps the peace.

I think that increasing income inequality encourages the wealthy to change the police’s function from keeping the peace to keeping the power. Western society use to be extremely violent with everyone not only armed, but also very, very willing to use their weapons, because they were effectively the only real law. It might be better to say that the authorities were not really concerned about protecting the rabble using a legal system, but of only protecting their power with whatever passed as a legal system or even government. Once the idea of the “king’s peace” where the government was supposed to protect everyone with it being the sole user of violence the population gradually became less armed and less violent. People accepted the quid pro quo of giving up their weapons and not being (by our standards) violent crazies and ceding justice and vengeance to the government.

We have a society where all the rungs of the ladder, the fine gradations of economic and social success, are gone. Failure use to mean going from a private school to a merely very good public school. Going from the big house to a smaller house or a very nice apartment. Going out less often or not having a cabin on the lake. Today, failure means living in a crappy apartment perhaps because you didn’t make it to an Ivy League university. Becoming homeless use to be hard, now it is hard not to be.

Those on the top are well rewarded, but the cost of failure is greater, and the margin of error is growing less, so the incentives for corruption is greater. Besides how can most people make a decent living now? By getting a good job or being corrupt?

This is really revealing and brought to mind a few questions/thoughts…

Firstly, Agatha Christie and Rex Stout had this one figured out, and their mastery was exploiting the trust factor in the reader to obscure the culprit behind more easily believable red herrings etc, but in the denoument no one is surprised by the reveal that it was indeed this same situation, the last gasp of a desperate individual…

Once you fall down below that threshold, your prospects are really dramatically worse, and you need to get back up immediately. This makes stealing a worthwhile risk. If it happens to succeed, it’s the only action with a big enough quick win to leap you back over the threshold in one bound. If, as is likely, it fails, you are scarcely worse off in the long run: your prospects were dire anyway, and they can’t get much direr. So the riskiness of stealing – it sometimes you gives you a big positive outcome and sometimes a big negative one – becomes a thing you should seek rather than avoid.

As I went on it occurred to me that this was the worst part of the great recession, we bailed out all the untrustworthy so as to protect the trustworthy, so there was no just ending, the story continues and is arguably worse now in aggregate, not just among poors. We could then take the grouping of just the wall st community (I know I know, bear with me here) and leave out all other groups. This post exposes the dynamic driving the fire sector now as well as in the past so at the deme/clique level it gets concentrated and the incentive to steal is vibrant in the wealthy, thus k streets role in protecting them from punishment, and ever increasing the level of distrust.

I remember visiting a house for sale, in a high end neighborhood in Northern California, after the USA housing bubble price crash (2012?).

The kitchen was missing some plumbing fixtures and the garbage disposal was gone, as I recall.

Per the realtor hosting the open-house, the foreclosed owner and his son had broken into their former house and stole the plumbing fixtures.

The previous owner could not have netted much money, but had probably lost a very large down payment and suffered a large drop in status as his family was evicted from this very good neighborhood.

It was a petty crime, and his eventual legal bills may have exceeded the captured stolen value by many times, but, at the time of the act, he probably felt the theft was somewhat justified.

One thing I’ve noticed is that our striving-through-consumption society, many people several times better off than me are just getting by month to month and are deeply in debt. (Cue Veblen). And when someone like this does fail, they’re told they should have been more frugal – but if everyone did that the economy would collapse. Life is a battle between the lenders and the spenders, and the spenders lose usually, except that if you DON’T spend, you end up consigned to the despised masses.

Obviously there are shrewd ways of making this work , but it’s a fine balance requiring good luck and often deception.

That’s an analytic description of lived life in our society. Behind it lies capitalism, media manipulation, our credit system, etc. ,but many caught in the net don’t even understand what’s happening in their own direct experience.

They’re told they should have been more frugal – but if everyone did that the economy would collapse.

Yes. On top of that, factor in all the job offshoring, for-profit insurance, Payday loans, and we may as well start planning the funeral for America’s unfettered capitalism. It’s coming.

Income inequality is miserable for the majority of the population, just ask the Americans. The one thing I think gets neglected in the discussion of income inequality is the psychopathic behavior of the people who have the most money and power. What makes people who acquire extreme wealth start behaving like non-people? They can’t relate to the society they control. The US ruling class wants to create nuclear weapons that are more powerful and accurate so they can have a nuclear war and hopefully control the world’s land and resources. They always want more. This is insane, and these are the people who have enormous control over the US. What’s wrong with these people?

Societies with higher levels of inequality have more crime, and lower levels of social trust. That’s quite a hard thing to explain:

I believe an English expression or two will clarify

1. Lord of the Manor – That’s me and my family, or not me and my family.

2. Thieving peasants – That’s me and my family out of necessity, or not me and my family.

3. My home:

Holkham Hall is an 18th-century country house located adjacent to the village of Holkham, Norfolk, England. The house was constructed in the Palladian style for the 1st Earl of Leicester by the architect William Kent, aided by the architect and aristocrat Lord Burlington

Holkhahall has 365 bedrooms, I’ve read somewhere.

I either live there or I’m a guest, or I’m a peasant and will never live there.

The article assumes a single threshold of desperation and also seems to exclusively study the bottom end and ignore high level crime. For a blatant example, our Trump has an infinitely high threshold of desperation and can never be satisfied — a “hungry ghost “. People generally have some level below which they can’t imagine falling, and they will act desperately or perhaps shrivel up or collapse if they fall below that level.

So there you have someone who subjectively needs to maintain some moderately high income level, and who might well have to spend lavishly on appearances in order to stay there at all, and who has gone into debt to maintain that level, and then something happens to his income. Their options will be crime, despair, and self-transformation (which would require the transformation of the rest of the family) and I suspect that the third is the rarest.

Just to add: striving, “hope”, and self-improvement are sacramental in our society, so

Everyone always needs more and everyone always has someone above them and someone below them, and even if there were no real poverty there would not be equality.

I am sort of expanding the original idea from the inequality and desperation of poverty to the inequality and desperation of an insecure hierarchy.

Does this analysis mean that we can have high inequality as long as everyone is at least above the threshold? In which case we have zero crime.

The threshold appears to dependent be an individual’s measure of utility. Not an objective measure.

Which means it will be nigh impossible for everyone to be above the line, because the humans involved keep moving the line (usually upwards in $ cost).

Keeping up with the Jones, ab asurdem.

p fitzsimmon: Pretty much what I just denied.

First, this is kind of old news. “The law, in its majestic equality, forbids rich and poor alike sleeping under bridges, begging in the streets, and stealing loaves of bread” – Anatole France (1894)

Personally, I’d relate inequality to the level of police violence, too. My police friends are working stiffs who increasingly face people in desperate circumstances. It used to be common wisdom that welfare was a cheap price to pay for social peace. When Clinton and Newt Gingrich conspired to “end welfare as we know it,” it threw a half million adults off of food stamps. Before that “end,” 76% of those who needed public assistance got it. After: 26%. Democrats are certainly not the party of the poor any more.

This post describes results obtained by running a model with agents operating in a model world with a non-linear utility function characterized by a threshold of desperation — a level of resources below which it becomes desperately hard to participate in your social group any more, below which you become destitute. The model belongs in “the rational-choice tradition: it assumes that when people offend (we are thinking about property crime here), they are not generally doing so out of psychopathology or error. They do so because they are trying their best to achieve their goals given their circumstances.”

I regard such modeling as neither amazing nor informative. A model with a built-in trigger point will trigger when the agents in the model are pushed past the trigger point. Little harm is done as long as the authors stick to drawing inferences about the behaviors of foraging birds but before drawing any conclusions about human behaviors in a society with high ‘inequality’, high ‘crime’, and low ‘trust’ — I believe the authors should spend some time in criminal court listening to the hearings. I believe they might begin to question the assumed “rational-choice” driving the actions of the defendants in the great proponderance of hearings. I also believe the authors might begin to reshape their notions of what is a ‘crime’ and what is not treated as ‘crime’. While in court they might also note who appears represented by an defense attorney working for a fee, and who appears represented by a public defense attorney. That might give them fuller understanding of ‘inequality’. In his comment above, David has already pointed out the lack of clear definition for the key model parameters.

“We are not thinking of the threshold as literal starvation. Rather, it’s the level of resources below which it becomes desperately hard to participate in your social group any more, below which you become destitute.” This notion that loss of status and inability “to participate in your social group” might be regarded as in some way equivalent to a social starvation strikes me as problematic for interpreting the trigger event in the model’s non-linear utility function. The conclusion the authors draw that:

“If your resources are around or below the threshold, however, then, under our assumptions, you should pretty much always steal. Even if it makes you worse off on average.”

— leaves me questioning the assumptions that lead this conclusion. Inequality is implicit in assuming a status difference necessary to there being status striving, or status “starvation” but does inequality drive human action or does envy and — in the case of status “starvation” — precarity?

The post’s concept of ‘crime’ in terms of “theft” is remarkably limited both in the scope of its view of ‘crime’ as well as limited in terms of the “theft” covered by the assumption: “Much of the extra crime in high-inequality societies is committed by people at the bottom end of the socioeconomic distribution ….” I suppose violent crimes against persons which also increase with increasing pecuniary, status, or social inequality are exogenous to this model’s characterization of crime. The thefts perpetrated “by people at the bottom end of the socioeconomic distribution” hardly compare to the thefts perpetrated by people at the topmost ends of the socioeconomic distribution. I suppose those high-end crimes are also exogenous to the modeling efforts since the criminals at the topmost ends of the socioeconomic distribution have constructed laws carefully excluding their crimes and crippling the prosecution of their crimes when they are illegal.

In my opinion, adding a “desperation threshold” to “behavioural-economic games” seems of little practical value for predicting how “people really do respond”. Behavioral-economic games impress me as about as meaningful in understanding and explaining human behaviors and human society as Skinner boxes were for understanding and explaining rat behaviors and rat society. [Perhaps with the exception of the behaviors of rats punished no matter what choices they made.]

This is by far the hidden gem of the comment section; directly responding to the OP with clear criticisms and extensions. It is not surprising at all that in a model where agents see social failure as equivalent to death, that those agents will take enormous risk to ‘keep up with the Joneses.’

As far as toy models go, this one is less useful than the many (narrative or statistical) put forward, un-academically, over at interfluidity (c.f. https://www.interfluidity.com/v2/7629.html)

People are basically tribal, and if you are a member of the lumpenproletariat, it is us against them. If the cops see you coming, they are going to hassle you. The people in the pretty houses are going to call the cops on you if they see you hanging around. There is team property, and there is team unproperty. Its not stealing if you take it from them, so you are going to steal in accordance with the rules of the propertied. Not to mention some people are just antisocial and are going to do it anyways.

Inequality fosters social division, social divisions create an insider/outsider dynamic, and the insiders are going to take advantage of the outsiders. If the insiders can pay the cops and judges, then its legal. If they can’t, then they are criminals.

The problem with this study is the individualism it posits. People are not mostly individualists. They have social identities embedded in groups, and behave differently toward outgroups than ingroups. People in America aren’t starving, they are living homeless shelters or sleeping in cars and eating at food banks. Plus, if you look at the disproportionate young maleness of most criminal behavior, there are obviously other factors going on.

“Chicken and Egg” on the go here.

I propose that high crime and low trust produce inequality.

If you’ve ever raised a child, you’ll know that human beings are born greedy. They have to be taught self control (id and ego), which they generally internalize through developing trust and empathy with a caregiver. Left to their own devices, their natural state is avarice and mendacity.

The question is not why do people steal and abuse others — it is why don’t they? They don’t when they are secure in the knowledge that their needs will be met by those around them. This is the social contract that is violated by extreme inequality.

I’ve raised two children to adulthood and am one of those awful people drawing a CalPERS pension after working in the criminal justice trenches for 34 years, and have given some thought to this problem over the years.

Having raised two children to adulthood, I do not believe avarice and mendacity is the natural state of children or adult humans. I do believe children rapidly learn socialization from the adults, and other children around them. I do believe there is a certain small proportion of Humankind in the US population that lacks empathy, and tends toward unconstrained avarice and carefully crafted mendacity. I believe these sociopaths have an uncommon tendency to rise to positions of power and authority in US organizations of Business, Government, and Crime and as a consequence these sociopaths wield an overlarge and most unfortunate power of influence and coercion directing US society.

I believe only certain people seem inclined to steal and abuse others. Some of these were brutalized by their socialization. Those naturally inclined to steal and abuse others quickly rise to positions of power in US societies and spread their corruption.

As someone who worked in the trenches of the criminal justice system didn’t you notice that a growing proportion of your charges seemed to have mental health problems? As someone who worked in the trenches of the criminal justice system, what is your assessment of the effectiveness of the US penal system in accomplishing its penitentiary goals? How effective is the criminal justice system at helping those it releases back into society return to a place in society? What kind of society is there for them to return to? What kind and quality of ‘Justice’ have you seen demonstrated by the US criminal justice system?

I must respectfully disagree. Empathy is a learned behavior.

I also have found that lying and stealing are quite common behaviors, even among those who have internalized a modicum of empathy. However only a tiny percentage of the population are true sociopaths who are a danger to the personal safety of others. In my experience “mental health” problems generally tend to be related to petty crime and substance abuse, not to serious offending.

The criminal justice system is an utter failure at deterring or changing behavior such as lying and stealing — and substance abuse and mental illness. It does a decent job of deterring the truly dangerous, by identifying and incarcerating them. The justice process would be far more effective at providing due process and fairness if the “stick” of incarceration were reserved only for those who pose a physical danger to others.

We would be far better served as a society if we used a “carrot” approach rather than the “stick” to deal with the common human behaviors like lying, cheating, stealing, and getting wasted. In the U.S. this is a completely alien concept, because it is “socialistic,” but I believe that most people have learned sufficient empathy to tamp-down their natural tendency toward avarice and mendacity if they see their material needs being met in a measure equal to their neighbor.

I agree with the author that inequality breeds “crime” — but we need to engage in more subtle distinctions about how we define “crime.” Toking on a reefer does not make one the moral equivalent of Charlie Manson.

I disagree with your characterization of human nature. But I am constrained by my own fondness for arguing about politics and society from a starting point of human nature — and particularly unfond of Hobbes’ notions of the essentially selfish nature of Humankind. I hope preschool and kindergarten teachers might weigh-in to suggest a more nuanced view of the ways of children than you or I have expressed.

I agree that empathy is a learned behavior but I believe lying and stealing are also learned behaviors. I agree that mental health is generally at play in petty crimes. My experience in criminal court was with sitting in a municipal court waiting for my son’s hearing. I recall very few hearings serious offenses and of those the seriousness was more in the punishment than in the offense itself. However, even in those few hearings of serious offense I heard, the defendants impressed this poor laymen as seriously lacking in the qualities of a clear and healthy mind. This is not to say I doubt that there are serious offenders of true malice who present a clear danger to society. The few defendants charged with serious offenses that I saw were definitely a danger to society. The anger I perceived in them was beyond my comprehension and suggested madness to me. I was impressed by the total lack of reflection or thought shown in the actions of another defendant, who seemed to have acted completely on impulse — albeit a murderous destructive impulse.

Your knowledgeable assessment of the criminal justice system is close to my own far less knowledgeable assessment. I disagree with your judgment that it “does a decent job of deterring the truly dangerous, by identifying and incarcerating them” — perhaps because I am thinking of a category of offender you may have seldom or never seen. I believe the criminals in banking, finance, Pharma, the MIC, and governance are far more destructive and dangerous than the worst criminal offenders in high security prisons. Their crimes visit harms across the reaches of cities, counties, states, and nations and work to unravel the fine cloth of our society. They have crafted the pecuniary, status, and social inequality that is the topic of this post. They are rewarded, enabled, and protected by this inequality they have built.

I appreciate and value this exchange of comments. I believe we stand on common ground. However, I would offer one final disagreement: “… [I] am one of those awful people drawing a CalPERS pension after working in the criminal justice trenches…”

is in error and if I may correct it for you:

“… [I] am one of those people drawing a pension from [the terribly mismanaged] CalPERS after working in the [awful] criminal justice trenches….”

I suspect you are also among the sort of people who kept my son — who was a serious offender — safe from the predations of other much more dangerous and serious offenders. My son has told me he felt safer when he was in jail than he felt in some areas of the state mental hospital — although he also made clear he had heard from other patients about other jails in other counties where he would and should fear for his safety and his life. Thanks.

Thank you!

I don’t disagree about the banksters, but I think that wealth confiscation would be a more effective deterrent to their avarice and mendacity. Imagine Jamie Dimon having to move out of his penthouse into a Section 8 apartment, and having to drive his hooptie ’91 Civic to buy expired bread and rotten produce, as we force so many poor people to do. That example, plus a decent “cop on the beat” examining the books would be an excellent deterrent to future financial crises without having to incarcerate so many people in overcrowded institutions.

I do think that empathy is formed in infancy, based on the children of addicts I’ve seen, and observing the trajectory a young man adopted at 4 from a Russian orphanage who I’ve known since he arrived in the U.S. By pre-school or kindergarten most kids whose needs have been met by a caregiver are already empathetic. Perhaps my view is quite a bit more subtle than Hobbes, but there you have it.

So sorry that your son took you on a tour of our woefully inadequate institutions.

Such depressing output in the post-Trump era. I was hoping for more solutions and fewer funerals to posterity. That were would be lines of concerned citizens outside Biden’s office like an American Idol audition for the next New Deal.

I had mixed feelings over the message from the socially distanced ex-presidents. An earnest transfer of responsibility should weigh as much as a peaceful transfer of power. Low trust and high crimes indeed…

I do not understand your your comment. You are overly elliptical. What funerals to posterity? Why would you expect lines of concerned citizens outside Biden’s office given the way access to US Presidents is constrained to those who pay to play — and they don’t have to wait in line — hats-in-hand. They make appointments. The “Next New Deal” — what “Next New Deal” are you imagining? And what was the message from the socially distanced past Presidents that you reference?

“An earnest transfer of responsibility” should take place behind closed doors between incoming and outgoing Executive branch appointees. The Trump Executive Branch did not accept a transfer responsibilities or knowledge from the Obama Executive Branch. Many of the Trump appointees worked to dismantle or disable the agencies they were entrusted with. I am not sure what kind of transfer of responsibility or knowledge Trump appointees could offer to Biden appointees … many of whom were formerly in the Obama Executive Branch.

But what do these matters have to do with “low trust and high crimes”, or with the post’s topic of inequality and its impacts on trust in Society and the level of crimes committed by members of the US lower socioeconomic groups?

I expressed an attitude in a short format comment. Asking so many questions doesn’t give us much common ground to start on.

What does it have to do with the article? Causation and expanded context. Criminality and low trust occupies the top as well as the bottom. The push towards increasing inequality began with top down policies.

How did lower crime, higher trust societies devolve into the current state of affairs? It’s a unmoved prime mover conundrum. Corrupt self serving bureaucrats abandoned society. They fail upwards and are insulated from crisis. But for this to occur, we would need to question assumptions about the initial conditions of competent liberal democratic societies.

“It’s a model in the rational-choice tradition: it assumes that when people offend . . . . They do so because they are trying their best to achieve their goals given their circumstances.” And, . “If your current resources are above the threshold, then, under the assumptions we make, it is not worth stealing.”

The model and its assumptions appear to be not only contradicted, but falsified by the real world choices of, at least some, financially robust economic actors operating in a free market jungle that seems to encourage, enthusiastically enable, and support such behavior, i.e. fraud, theft, general criminal behavior, ect.. How is that so?

1. “Illegality is ubiquitous in today’s financial markets.” See for example,

“What to Expect From White-Collar Prosecutions in 2020”

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/14/business/dealbook/white-collar-crime-2020.html

2. “There’s Never Been a Better Time to Be a White-Collar Criminal”

https://newrepublic.com/article/158582/theres-never-better-time-white-collar-criminal

3. “. . . . the idea that corporations have a strong antisocial character had already been expressed at the dawn of the twentieth century by Edward Ross, who characterized them as entities that “transmit the greed of investors, but not their conscience”. Subsequent research on corporate crime has reaffirmed the central role played by the emphasis on profit maximization in explanations for illegal acts committed by corporate executives.”

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-journal-of-sociology-archives-europeennes-de-sociologie/article/div-classtitlewhite-collar-crimediv/6319DD3CF3DABC0F5C6B9ACCDED2E816

The corporate veil not only limits one’s risk to money invested, it also insulates one’s empathy from guilt for crimes committed by the same corporation.