Yves here. This post explains the seeming contradiction of severe Covid-induced distress in many sectors of the economy, such as restaurants, retail stores in central city office districts, hotels, personal services, with a decline in the number of bankruptcy filings. The authors attribute the disconnect to government support, which they argue will decline before there’s enough improvement in fundamentals to get business owners out of their hole. Remember also some US states and cities have imposed rent and/or eviction moratoriums. That does not make the payments away, but merely defers when they have to be paid. And when those stays of execution end or are about to end, it’s not hard to think that that alone will trigger additional bankruptcies.

Another factor that some have argued is working in the US is that a higher proportion of businesses than normal are closing not by using the bankruptcy process but by simply shuttering their operations. The argument is that for small businesses, bankruptcy almost always means a personal bankruptcy too, since most lenders require the owner to guarantee the obligation personally. A personal bankruptcy makes it hard to get credit or a new job, so it’s better if possible to wind up a business rather than resort to bankruptcy. And as much as it is draining to shutter a company, bankruptcy is even more so.

Can readers provide any intelligence about the fragility of businesses in your area, and if waning government support is increasing distress?

By Simeon Djankov,Policy Director, Financial Markets Group, London School of Economics and Eva (Yiwen) Zhang, Researcher, Peterson Institute for International Economics. Originally published at VoxEU<

Bankruptcies have fallen sharply in OECD economies because of the array of COVID-related support available to businesses, as well as imposed moratoria on bankruptcy filings. This column argue that this situation won’t last, and that governments should start planning for a surge by the end of 2021 – ideally by reforming their bankruptcy laws, as the UK has done, and lessening the burden on courts.

Bankruptcies have fallen sharply in OECD economies because of the array of COVID-related support available to businesses, as well as imposed moratoria on bankruptcy filings. This column argue that this situation won’t last, and that governments should start planning for a surge by the end of 2021 – ideally by reforming their bankruptcy laws, as the UK has done, and lessening the burden on courts.

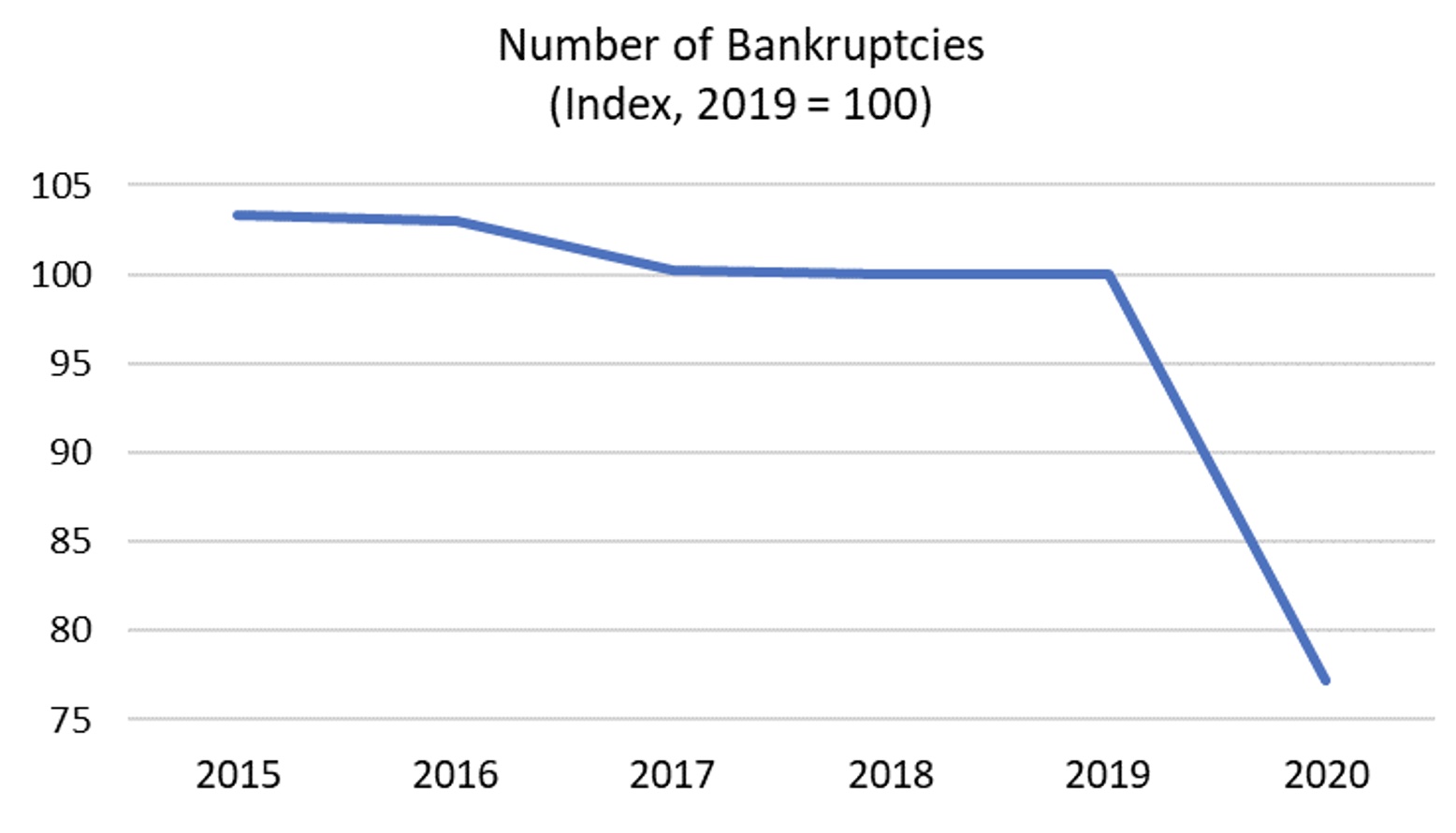

Economic crises bring an upturn in bankruptcies. Companies suffering losses struggle to survive, and many fail. A wave of bankruptcy filings was expected in the wake of COVID-19 too (Bailey et al. 2021). Yet during 2020, the number of corporate bankruptcy filings in most advanced economies – members of the OECD – fell by 17% relative to 2019, and by even more relative to previous years (Figure 1). This decline in bankruptcy cases demonstrates the success of the initial COVID-19 response measures. On second glance, however, it brings worries too (Blanchard et al. 2020).

Figure 1 Average 2020 bankruptcy filings are 17% lower than in 2019

Note: The index is based on total number of bankruptcies in 25 advanced economies (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Japan, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. For 12 economies (Australia, Belgium, Canada, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Turkey and the United Kingdom), the latest available data (most often to November 2020) are annualized to 2020 annual aggregates.

Source: Authors’ calculation using national data (accessed through Macrobond on 26 January 2021).

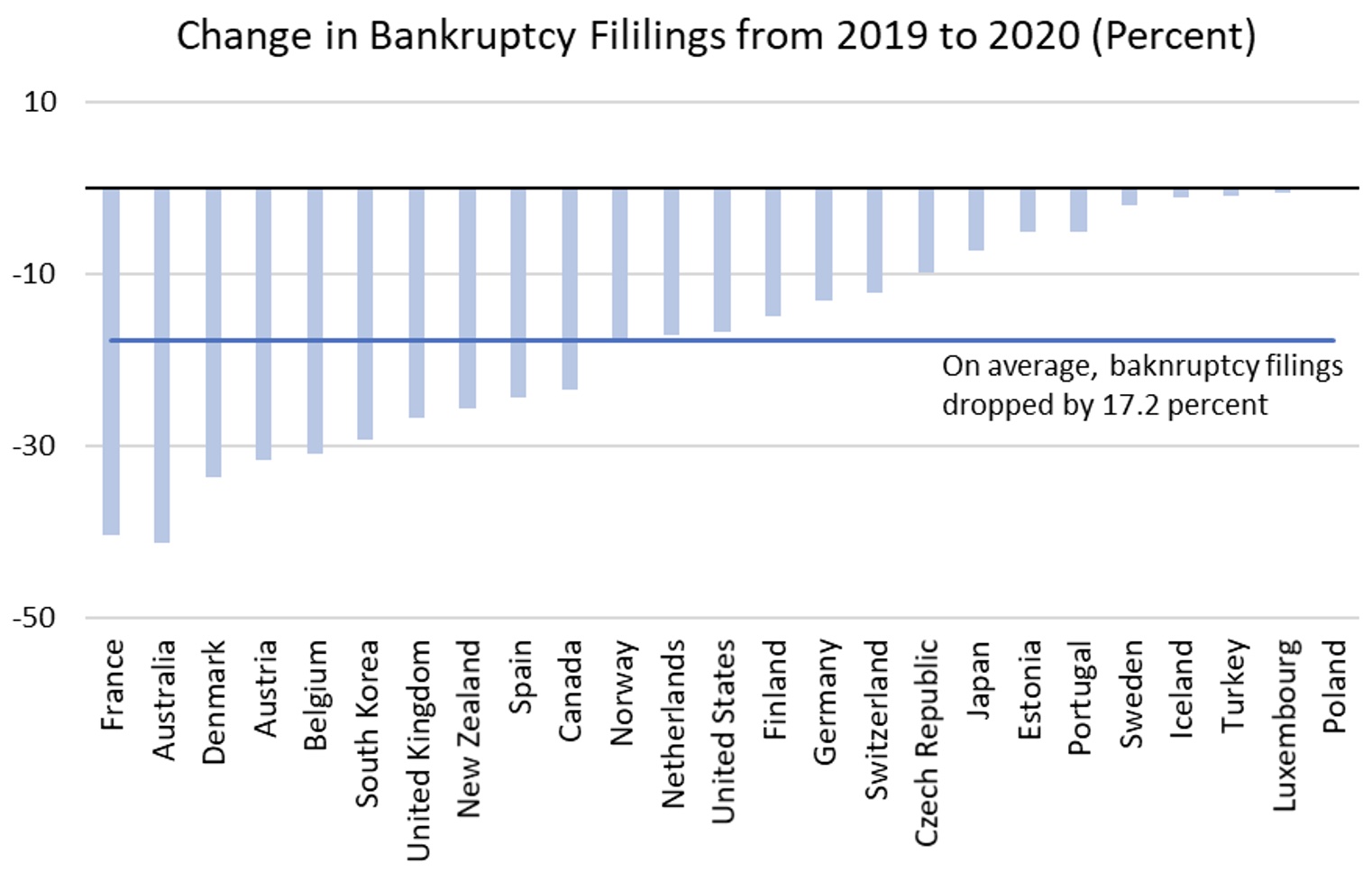

Bankruptcy Filings Have Declined in 24 of 25 Advanced Economies

Data for 2020 are available on bankruptcy filings in 25 OECD economies. In the US, these fell by 16% relative to last year. The other major economies show the same pattern of decline. In Japan and Germany the falls are 7% and 13%, respectively; in Canada and the UK, bankruptcies fell by around a quarter (Figure 2). The largest decline is in Australia and France (40%), while Poland is the only country that shows no change relative to 2019.

Figure 2 Bankruptcy cases decline across advanced economies

Note: The index is based on total number of bankruptcies in 25 advanced economies (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Japan, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. For 12 economies (Australia, Belgium, Canada, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Turkey and the United Kingdom), the latest available data (most often to November 2020) are annualized to 2020 annual aggregates.

Source: Authors’ calculation using national data (accessed through Macrobond on 26 January 2021).

The reasons for this decline are twofold. The COVID-19 pandemic has induced governments in many advanced economies to finance job support programmes to assist workers and to temporarily halt bankruptcy procedures – providing lifelines to keep firms alive through the crisis, at a time when premature bankruptcy can worsen the recession. The job support programmes have been updated and expanded in most OECD countries, while the bankruptcy moratoriums are expiring soon in many countries. Australia, for example, returned to normal bankruptcy procedures on 1 January 2021 (Australian Financial Security Authority 2021).

For many employers and businesses, the government programmes have worked. Businesses have reacted by keeping employees on board or hiring new ones when restrictions on business operations became less onerous. In turn, the support keeps businesses open, in the hope that the economy turns around.

This availability of plentiful financial support to businesses cannot continue for long. A large number of firms will need debt restructuring once government support programmes run out and the courts open up. Extensive reorganisation or liquidation procedures, which may work in normal times, will prove insufficient to service a large wave of insolvencies. Changes to existing regimes should be done now, before the wave on bankruptcies comes. In March 2019 – a year before COVID started closing down businesses – the European Parliament adopted a new directive on preventive restructuring, aiming to increase the efficiency of insolvency proceedings (Becker 2019). The Reform Directive specifies that a new procedure must be in place in all EU member countries by 2022. The UK has done just that and thus provides an example for other governments to follow.

The UK Has Added Three Features to Its Bankruptcy Law

The amendments to the UK insolvency law, adopted in June 2020, add three features (Balloch et al. 2020). First, these amendments introduce a two-month moratorium, during which the company benefits from a payment holiday from the majority of its debts. Second, the amendments allow the debtor to propose a rescue plan that can be forced onto every creditor if the majority of creditors agree. Third, suppliers are prevented from stopping deliveries once they find out that the debtor has trouble paying creditors, as long as the firm pays for its supplies on time – even ahead of bank creditors. Research on bankruptcy procedures around the world (Djankov et al. 2008) shows that the type of changes the UK has enacted increase the likelihood firms will survive, as they continue operating during their restructuring.

Some economists are concerned that keeping insolvent firms alive will drain resources from the healthy parts of the economy (Acharya 2020). These fears are fundamentally misguided. Policies to force businesses to shut down permanently risk slowing down the COVID recovery (Laeven et al 2020). As businesses shut down, they break a supply chain that affects other businesses, including in healthier sectors. Such breakage should be avoided as much as possible.

See original post for references

I think a lot depends on the operation of the local property market. Here in Ireland a neighbour who works in one bank said that there is a terrifying amount of non-payment going on with rents and commercial mortgages. Businesses that are suffering have stopped repaying, perfectly good businesses have decided to join them to see what happens, landlords aren’t paying their mortgage loans, and every is pretending it will all somehow work out in the end when the magic vaccine fairy solves everyones problems.

Because of the importance of maintaining book value, this can lead in a downturn to perfectly sound businesses getting closed because landlords prefer to keep a unit empty rather than accept lower rents in order to pretend it still has its original capital value. But likewise, some landlords/banks will be desperate for cash flow, so will accept reasonable compromises. I don’t know how this will work out for the food/bar industry as many units will only be profitable at lower rents for the foreseeable future as it will take time for pre-Covid demand for entertaining to get back to normal.

In my local area, I’ve noticed quite a few empty units taken up by cheap and cheerful pop up type operations, mostly for takeout food, and anecdotally I’ve heard that a lot of small scale crafts people are taking advantage of the situation to get shop front type units in small towns. But most of these will be on very short term lets. The question is what landlords and their funding sources decide to do if and when an upturn comes. Do they stick with these new businesses, or shut them down hoping for more conventional tenants? I really don’t know and I suspect they don’t know either.

Closures up in Upper Northern Michigan have been occurring, usually the businesses wind themselves up – but, believe it or not, we are in a boom of having many new medical marijuana places opening – you have to travel over into the next county for recreational use.

I follow the commercial real estate sector in SoCal and can attest to a significant deterioration in cash flow, many office building operating at 30 to 50% occupancy some totally empty, tons of closed restaurants, (many business owners used the government loans to wind up their businesses).

I think it will take years for things to go back to normal.

However asset prices haven’t come down at all and commercial buildings are listing at all time high prices.

I see some restaurant buildings that sold pre-covid for $800sqft now listed at $900sqft and more. Very little product is moving but prices are holding up for now.

“And as much as it is draining to shutter a company, bankruptcy is even more so.”

Hello Yves, Alena here from Geneva, Switzerland. I am a small business owner, I do airport transfers. For an individual business owner it costs 4000 swiss francs to file a bankruptcy here in Geneva. You have to pay beforehand. So I prefer to continue paying all the social charges and other (as tax on tourism) even if there is no business for almost a year now and with no perspective of recovery this year. After a year of misery there is no cash to file bankruptcy. So I think people are waiting. The local government keeps promising help but so far restaurants, hairdressers, gym clubs and others (such as theaters) that have to pay rent are still waiting for help. For employees, there is benefits payed by the Confederation and even for individual business owners who declared at least 10’000 swiss francs net revenue in 2019, but no help for social charges or rent. In june and july 2020, there was a one time loan for all businesses guaranteed by the Confederation of maximum 10% of the 2019 gross revenue of the company ( whitch I find ridiculously low). The loans were interest free and to be repayed in 3 years time. But by the time the second wave hit, people had already used all of their “covid credits” and due to a few but very expensive cases of abuse, the federal government refused to grant a second loan. The “bourgeois” party also refused federal help for commercial rents. Their argument is rather vaguely something about the Economy changing and we don’t want to give money to businesses that won’t be profitable in the post-Covid world, or do not deserve to survive…

Which is very sourly way of putting things if you have to fight every day against companies such as Uber.

Yours Sincerely, Alena