Yves here. This important analysis debunks the widely-held view, promoted by the media, that the Democrats lost many 2020 Congressional races despite outspending the Republicans.

By Thomas Ferguson, Director of Research, Professor Emeritus, University of Massachusetts, Boston; Paul Jorgensen, Assistant Professor of Political Science, University of Texas-Pan American, and Jie Chen, University Statistician, University of Massachusetts. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

The 2020 election and the cataclysmic series of events it triggered have left many Americans dazed and sometimes even breathless. Not the least of these shocks stems from the Democrats’ unexpectedly poor showing in Congressional races. While narrowly winning the presidency, the party actually lost seats in the House and failed in its bid to take control of the Senate. The disappointment – or relief for Republicans – was all the greater in that in the weeks before the election, virtually every major media outlet pushed out stories trumpeting what was said to be overwhelming Democratic advantages in fundraising – more than twenty, by our incomplete count.

The morning after the election, though, the press flip-flopped. No one stopped to wonder if the mid- and late-October pre-election counts were misleading or simply wrong. Instead, the major media ran story after story highlighting the extravagance of strong claims about the money-driven character of American elections. Reporters celebrated how canny voters in Maine and other states saw through the clouds of out of state big money. Our favorite summary – it should be enshrined forever in the Madame Tussaud’s of hasty social science misjudgments – was a tweet by Edward Luttwak that “The very good news of 2020: money does not win elections in America. Because of the proclivities of American billionaires, Democratic candidates had x2 or x3 or x4 the money of Republicans in House, Senate & WH elections. Holder, Obama’s AG spent hugely in States but Dems lost.”

Last year’s presidential race is sui generis and fraught with chilling lessons for the future of American politics. We will analyze it carefully another time. Our concern here is with the Congressional elections. In contrast to presidential runs, races for the House and Senate are not one-offs. The hundreds of cases permit real generalizations.

Before the election, when we were asked, we cautioned about claims of a one-sided Democratic advantage. We did not doubt the stories drawing on partial, pre-election fundraising reports, testified to strong Democratic fundraising efforts. Nor, though we wondered about the margins, did we doubt that the Democrats were probably then ahead in the polls.

But we have tracked money and politics through many election cycles. We knew the flows of money streaming into campaigns in the final weeks of elections are often gigantic. The epic, come from behind struggle in 2016 to salvage Republican control of the Senate was also fresh in our minds, since we had just published a study which analyzed it in detail.

That effort’s defining feature was a rip tide of late money that turned around what looked like a hopeless situation when most observers believed their party’s presidential standard bearer was doomed. In 2020, signs that similar efforts might be afoot were obvious. In Maine, for example, in mid-October, a single private equity magnate dropped his third contribution of $500,000 dollars in the election cycle into a single candidate super-PAC supporting Republican Senator Collins.

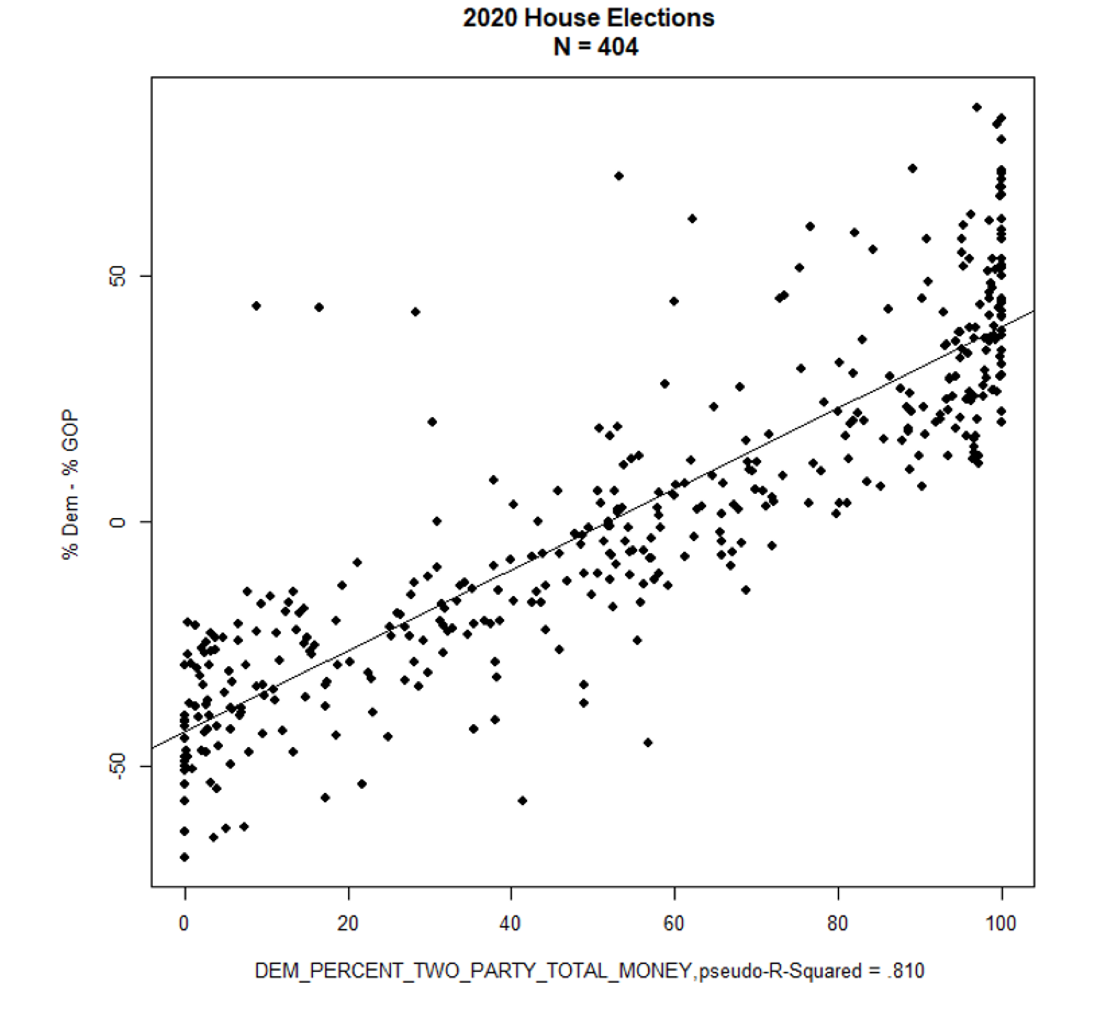

We were confident that our “linear model” of House and Senate races – so-called because the relation between the two-party split of the money and the outcome of the vote looks like a straight line when you plot it – would prove out, as it had in every previous election for which the data exists to compute it. And we doubted that trailing in the polls would put off many big Republican contributors, any more than in 2016. The whole point of our work is that most money rarely follows polls.

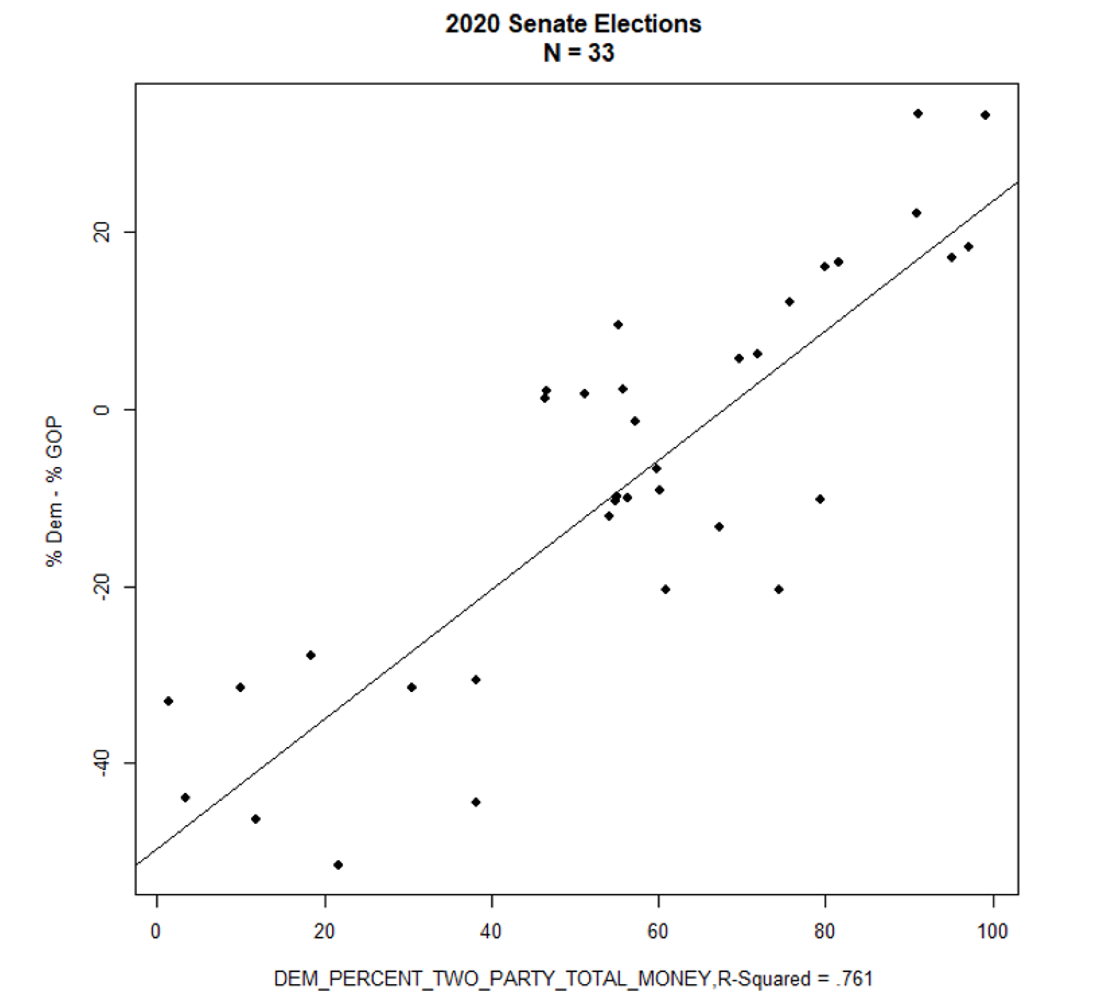

Figures 1 and 2 confirm we were right. At a moment, when everything appears to be up for grabs in American politics, some things have not changed: the system is still money-driven.

Do not be put off by the figures. They are simple scatter diagrams and easy to read. Along the bottom from left to right runs the Democratic percentage of the total amount spent on any given race – not the cost of votes per ballot or other measures that vary with district size and other characteristics. The vertical axis going up the left side benchmarks the percentage of the two-party vote that the Democrats garner. That axis is scaled as the difference between the Democratic and Republican shares of the vote, meaning that as the difference goes positive for the Democrats (roughly in the middle of the figure), they start winning seats. At the bottom left corner, in other words, the Democrats get no or hardly any money and win no or hardly any seats. At the upper right, they slurp in all the money and get all the votes.

The spread of the dots around the line – outcomes of actual races – shows how far reality diverged from the pure linear model. The discordance in 2020, as in so many elections before, was not much. Some races did deviate – they always do, and last year Democrats lost some close ones they might normally have won. But the big story is the continued dominance of the linear model. The best ways to summarize the model’s strength are highly technical, because in the House, almost always, and sometimes in Senate races, you need to take account of various races’ spatial relationships to each other. We tuck the details in our Appendix here, along with a brief explanation of how to show up the perennial last hope of orthodox political science and economics, that seeing cannot be believing, because the money must be following polls.)

Noam Chomsky has recently remarked that there are few real regularities discovered in the social sciences, but that the linear model is one.[1] After forty years of evidence, it’s time to agree and move on. The next time you wake up to find that election results in hundreds of Congressional elections differ wildly from what you would expect from the reported division of political money, check more carefully whether the voice of the people is not really the sound of money talking. And if you are trying to understand why both major parties instantly acquiesce to whatever it takes to rescue financial markets and the 1%, but fight over relief for the rest of us, you have the major part of the answer. The basic root of K-shaped recoveries is the hold political money has on both major political parties.

Appendix: Models, Methods, and Data

All our methods and data sources are spelled out at length in the Appendices to Thomas Ferguson, Paul, Jorgensen, and Jie Chen, “How Money Drives US Congressional Elections: Linear models of Money and Outcomes,” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 2019.

For 2020, as usual, we gathered all candidate disbursements and outside money from any source spent in support of the candidate, including negative advertising against opponents, to construct the percent of all money favoring the Democratic candidate in each House and Senate election. The campaign spending data derives from multiple Federal Election Commission datasets, containing candidate summary spending totals, independent expenditures (from Super PACs and dark money groups), party coordinated expenditures, electioneering communications (which we examine to clearly identify the support of or opposition to candidates), and communications costs (campaigning internal to some corporations and unions). Note that these include “dark money” totals, but not its real sources. The voting data come from David Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections.

For our models we drop races without two major party candidates; see our Structural Change and Economic Dynamics discussion. In many cases, those are best viewed as auctions. We always test for spatial autocorrelation in races. This is often present in House elections and sometimes for Senate elections. We include the final outcomes of the Georgia Senate races on our Figure 2, but since they were stand alones on a different day, not for calculating the model fit.

The strong linear character of the model, which holds for all elections for which data exists, has been a standing embarrassment to voter centered accounts of politics from the moment it was published. Many critical responses are simply silly; they don’t pay enough attention to details. But we take the force of the objection that in theory, the money could be following polls, in whole or in part, making the apparent correlation spurious.

The usual social science device to deal with questions of “endogeneity” is some form of instrumental variable. Those are often highly problematic. In our earlier work, we developed a spatial version of the latent instrumental variable model introduced by Peter Ebbes and analyzed in detail by Irene Hueter to assess such possibilities. Our Structural Change piece discusses these, but in addition shows how to use published gambling odds to confirm our conclusions that while two-way causality happens, it does not dominate; the 2016 Republican Senate recovery was a particularly dramatic case in point. Note that since we developed the linear model, other researchers find evidence for it in other countries; the pattern is not specific to the United States.

Our presentation of results here follows that in our longer essay. As usual, the House elections showed marked spatial autocorrelation based on a Moran I test. This indicated that the residuals of the OLS model displayed significant spatial dependence (PV(I) < .001). For the House we thus report, successively, results using ordinary least squares, then a spatial Durbin model, followed by the Bayesian spatial latent instrumental variable regression with 4 clusters we prefer, along with R squared and Pseudo R squared measures first for the OLS and then the spatial model, followed by a test for spatial effects and then N, the number of cases. Figure 1 showing results for the House displays the Pseudo R squared measure for the spatial model, since the Bayesian spatial latent instrumental model does not have such a convenient summary indicator.

House

| Year | OLS | Spatial Model | SBLIV4 | RSq/PRSq | PV(I) | N |

| 2020 | .825(.023) | .718 (.023) | .731(.679,.781) | .759/.810 | .000 | 404 |

Spatial models were unnecessary for the Senate elections, so the table does not show any. We present results for the OLS model and for a Bayesian latent instrumental variable regression with 3 clusters.

Senate

| Year | OLS

Coefficients ( SE) |

BLIV3

Median ( 95% CI ) |

R-square | N |

| 2020 | .732 (.074) | .729(.587,.873) | .761 | 33 |

Figure 1: The Straight Truth: Money and Major Party Votes in the House Data: Money From the FEC; Votes from Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections

Figure 2: The Straight Truth: Money and Votes in the Senate Data: Money From the FEC; Votes from Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections Display Includes the Special Senate Elections in Georgia in January, Though They Are Not Included in the Summary Statistics – See Appendix

Noam Chomsky has recently remarked that there are few real regularities discovered in the social sciences, but that the linear model is one.[1] After forty years of evidence, it’s time to agree and move on. The next time you wake up to find that election results in hundreds of Congressional elections differ wildly from what you would expect from the reported division of political money, check more carefully whether the voice of the people is not really the sound of money talking. And if you are trying to understand why both major parties instantly acquiesce to whatever it takes to rescue financial markets and the 1%, but fight over relief for the rest of us, you have the major part of the answer. The basic root of K-shaped recoveries is the hold political money has on both major political parties.

==========================================

WHY would anyone EVER doubt that the US political system serves the highest bidder? Or that money is the overwhelming variable in who wins an election. Only because our media is of, by, and for the wealthy…

As I like to say, the ruling class owns both politics and the media. The first through legalized corruption and the second simply by owning it.

Or vice-versa. Perhaps that’s how you become the ruling class.

Correlation isn’t always causation but maybe it is causation in this case. Or not. There might be alternate explanations, keeping the winning candidate happy by directing funds his/her way might maybe explain some of the correlation. The expected winner is likely the one someone might want to have as a friend. Spending money for an expected loser on the other hand might not make much business sense.

(the spending might indicate who the moneyed interests see as the likely winner in the same way as betting companies set their odds based on who they expect to win)

I’d have been more convinced if they somehow managed to adjust/correct for the safe seats, the gerrymandering etc. (I can’t see that they did this in the article, the linked to studies in the article were behind paywalls so maybe they did)

To me, your arguments seem to echo a variant of what I understand as

“the money must be following polls.” Worse, your arguments echo the Neoliberal concept behind the idea that a ‘Market’ for betting on election winners best predicts those winners by virtue of some mysterious wisdom of Markets.

Yes and no. The study can be seen to indicate that the candidate who was seen as the most likely to be in a position to help his/her friends after the election also had people willing to spend the most money to become his/her friend before the election.

Big money might have candidates they’d prefer to back more than the ones they actually do back, they simply decide to back the candidate most likely to get them the closest to what they want. A low risk low reward strategy that in theory can work well for a long time. Reality and theory don’t always match so markets and betting companies don’t always win.

I don’t argue that it should be like that, I am offering the possibility that it is like that.

Whether causation or just correlation – it doesn’t matter what you think, but what the elected politicians think. A poll of them would be helpful. But given their actions, I think what one would find definitely is that they regard it as causation. I realize modesty prevents Ferguson from doing so, but others need to start referring to his observation as a law rather than a theory.

I too was wondering what the study had done to consider the possibility that causation was not all in one direction, and that (so to speak) “every money likes a winner”. But the article does say the authors hadn’t neglected the issue: “[W]e take the force of the objection that in theory, the money could be following polls, in whole or in part, making the apparent correlation spurious.” And it adds, “Our Structural Change piece . . . in addition shows how to use published gambling odds to confirm our conclusions that while two-way causality happens, it does not dominate; the 2016 Republican Senate recovery was a particularly dramatic case in point. Note that since we developed the linear model, other researchers find evidence for it in other countries; the pattern is not specific to the United States.”

I also notice that Figure 1 says it only has 404 data points — which would presumably leave 31 races unrepresented on the graph. Considering how many points are at the two extremes of the X-axis: D vote = 0% or 100% of (D + R vote), the authors apparently didn’t leave out districts where only a D or only an R was on the ballot. (Though I suppose some of those might have been Top 2 races.) So which races are the missing 31, I wonder?

Many thanks for that. I missed it. I’ll try not to make the annoyance I feel about me missing it out on the authors…. I’d have preferred it if a competing/complementary theory had been written more about. I know, and therefore should have been more careful, that important information can be hidden in foot-notes and/or long paragraphs.

In some cases then highlighting a possible other explanation provides a reason to obtain more funding to research further, in other cases then I suspect that hiding other explanations is more likely to generate funding for further research as it is easier to obtain funding for research supporting the established wisdom.

If their theory is true then what might it lead to?

1. For politicians then it might lead to ‘pragmatic’ politicians looking for money where money can be found – the wealthy. The wealthy might then possibly elect to fund politicians who further the interests of the wealthy.

2. For the electorate then it might lead to a disengagement from politics by everyone but the wealthy. Why bother supporting a candidate if big money will win anyway? Defeatist.

Anyway, there is a saying about 50% of marketing being wasted and nobody knows which 50%:

https://www.forbes.com/sites/georgebradt/2016/09/14/wanamaker-was-wrong-the-vast-majority-of-advertising-is-wasted/

Nobody knows how much of the political advertising is wasted and I’m not sure if anybody is interested to find out. Possibly some actually changes peoples mind on who they’d vote for, I’d assume (without knowing) that the biggest effect might be to change peoples mind about bothering to vote.

They say in the appendix that they dropped races that did not have candidates from both major parties. So presumably there were races in which the Republicans fielded a candidate, but with essentially zero funding.

My impression was that Sander’s threat was two fold. The first threat was M4A because Medicare does compensate doctors and providers at a lower rate than many would like and over time with M4A the government would be able to control compensation rates at all levels even more. And the US spends 9000 per year per capita on health care compared to the next highest, Germany, at 5000 per year and China at 600. But the bigger threat especially to the Black Congressional Caucus was the funding model. Sanders somehow succeeded in collecting national election dollar numbers from masses of small donors nationwide. He was an existential threat to Congress. Destroying his candidacy was effective in getting someone who understands political economics in control but more importantly from what I have seen where I work the lower income Hispanic and Black and minority workers who skipped lunch and so much else to send a few bucks to Bernie are never going to make that mistake again to any candidate. They donated blood money. Many ended up voting insanely for Trump but most just did not vote. The financiers of Congress are simply paying for profits in Washington so their donations make a lot of sense and are emotionless and purely business. Of course, we have to admit that Sanders did not rise to the occasion and was unwilling to go to the mat for his supporters so he is a big part of the failure. If we cannot focus on campaign finance as an issue will the Republic survive in its present form? Who knows?

I sent money to Bernie, and I would send money again to a candidate like Bernie. I was and I am deeply disillusioned … but I continue to believe there will be a candidate in my lifetime who will make better use of the money I can and will contribute.

I believe you described what I believe is the Bernie “sheep-dog” effect Yves so strongly deprecated. After he voted for the CARES Act Bernie lost whatever small contributions I might/could make in the future. Today, I just sent a stack of Bernie posters and brochures for re-cycling. I never had a chance to campaign for Bernie in my state … WIN or LOSE! I remain puzzled by what real-life concerns and coercion twists Bernie from his ideals, though I continue to give due consideration to the practical gains Bernie might/could achieve. I am watching and waiting for Bernie’s ‘true’ successor — ‘true’ in a perfect rainbow of meanings.

I view the importance of your candidate accepting only small contributions from real people as necessary but not sufficient to make a better society, for him/her to act according to what his/her constituents want in the long run. In that way, there really needs to be a party that is non-ideological but just embraces everyone who accepts only small dollar contributions. Each constituency is different and each representative is different, but overall it would be closer to a true democracy.

If black and hispanic votes for Trump were motivated by revenge on the Democrats for being cheated out of Sanders, were these votes insane?

If I believe — as I do — that both the republican and democratic parties are the party of, by, and for Big Money, then why should Big Money care which candidate republican or democrat wins election … after the primaries have been properly guided. I believe this post regards elections after the primaries have selected candidates. What differences drive the evident bidding wars between factions/players of Big Money? There seem to be at least two, possibly shifting and ill-defined Big Money factions/players. There is also a higher dimension of the “chess” they play that assures neither democratic nor republican party should have too prominent a majority. And I believe that is one reason behind the mysterious life and death of the filibuster rules. Those rules provide secondary safeguards for the interests of Big Money.

Percentages can be misleading. Not that they are here, but I would like to see a plot with dollars spent on the winning candidate on the y axis and dollars spent on the losing candidate on the x axis, or vice versa.

And. OC, other dollar denominated graphs might be informative. For instance, dollars spent on the Republican candidate vs. dollars spent on the Democratic candidate. Also, dollars spent on the winner minus dollars spent on the loser vs. total dollars spent, and dollars spent on the Republican candidate minus dollars spent on the Democratic candidate vs. total dollars spent.