By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

“If a lion could speak, we couldn’t understand him” –Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

Unlike most of my posts, this post will not have a thesis. Starting somewhere, maybe here, in my perambulations through the Twittersphere, I ran across some links on trees communicating — for the moment, we’ll put aside the question of whether trees signal, communicate, or talk, or whether forests do — and I went down a rathole of research, some highlights of which I thought I would share with you. I found the research amazing and beautiful in itself, and the gardening and permaculture contingent in the readership may find it useful in their practice. The three main researchers seem to be Switzerland’s Edward Farmer, Canada’s Suzanne Simard (Ted Talk) and Germany’s Peter Wohlleben (YouTube). America’s George David Haskell also rates a mention (Ted Talk). However, my purpose is not to summarize their research[1], but to exhibit some bright shiny objects I picked up while going walkabout, and then conclude with some woo woo.

Unlike most of my posts on the biosphere, I will not begin with a classification system or taxonomy for trees. That might be a good thing: San Francisco’s ArboristNow urges that “we know what a tree is – but there is no precise definition which is completely recognized of what a tree is in ordinary language or in botany.” The Arbor Day Foundation disagrees, giving one. But then they would. Here instead is the simplest possible diagram of your standard tree:

I’m now going to make things even simpler, and give examples of how trees communicate above ground (crown and trunk), and below ground (roots)[3].

Communication Above Ground

Forms of communcation above ground seem to fall into two buckets: Volatile Organic Compounds[3], and electrical signals. (The electrical signals above ground are from leaf-to-leaf in the same tree; they are too slow and weak to travel through the air. That would not be the case for electrical signals send through a tree’s root system, however, as roots entangle below ground.)

Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs). From Quanta, “The Secret Language of Plants“:

It’s now well established that when bugs chew leaves, plants respond by releasing volatile organic compounds into the air. By [ecologist Richard] Karban’s last count, 40 out of 48 studies of plant communication confirm that other plants detect these airborne signals and ramp up their production of chemical weapons or other defense mechanisms in response. “The evidence that plants release volatiles when damaged by herbivores is as sure as something in science can be,” said Martin Heil, an ecologist at the Mexican research institute Cinvestav Irapuato. “The evidence that plants can somehow perceive these volatiles and respond with a defense response is also very good.”

The VOCs signal not only within a single species of plant, but between them, and even to insects! Quanta once more:

It turns out almost every green plant that’s been studied releases its own cocktail of volatile chemicals, and many species register and respond to these plumes. For example, the smell of cut grass — a blend of alcohols, aldehydes, ketones and esters — may be pleasant to us but to plants signals danger on the way. Heil has found that when wild-growing lima beans are exposed to volatiles from other lima bean plants being eaten by beetles, they grow faster and resist attack. Compounds released from damaged plants prime the defenses of corn seedlings, so that they later mount a more effective counterattack against beet armyworms. These signals seem to be a universal language: sagebrush induces responses in tobacco; chili peppers and lima beans respond to cucumber emissions, too.

Plants can communicate with insects as well, sending airborne messages that act as distress signals to predatory insects that kill herbivores. Maize attacked by beet armyworms releases a cloud of volatile chemicals that attracts wasps to lay eggs in the caterpillars’ bodies. The emerging picture is that plant-eating bugs, and the insects that feed on them, live in a world we can barely imagine, perfumed by clouds of chemicals rich in information. Ants, microbes, moths, even hummingbirds and tortoises ([plant signaling pioneer Ted Farmer of the University of Lausanne] checked) all detect and react to these blasts.

Trees being plants, the same communication pathways are available to them. From Smithsonian, “Do Trees Talk to Each Other?“:

Trees also communicate through the air, using pheromones and other scent signals. Wohlleben’s favorite example occurs on the hot, dusty savannas of sub-Saharan Africa, where the wide-crowned umbrella thorn acacia is the emblematic tree. When a giraffe starts chewing acacia leaves, the tree notices the injury and emits a distress signal in the form of ethylene gas. Upon detecting this gas, neighboring acacias start pumping tannins into their leaves. In large enough quantities these compounds can sicken or even kill large herbivores.

Electrical Signals. From PNAS, “Identification of cell populations necessary for leaf-to-leaf electrical signaling in a wounded plant“:

Organ-to-organ electrical signaling is a highly conserved feature of land plants. For example, wound-induced electrical signals known as “slow wave potentials” (SWPs; otherwise known as “variation potentials”) have been found in numerous species…. In Arabidopsis thaliana, severe damage triggers electrical activity that propagates from leaf to leaf with apparent velocities in the centimeter-per-minute range… Fast nervous conduction in animals evolved under strong selection from predators (34). Here we argue that pressures from herbivores have led to the evolution of leaf-to-leaf electrical signaling in plants…. Together, our results support the hypothesis that a primary role of SWP in plants is to activate defenses in tissues distal to wounds. Defense-related electrical signaling is therefore common to both the plant and animal kingdoms.

(Instrumenting this signaling is now a line of business, however tiny.) Farmer is a co-author of this piece, and he writes elsewhere of trees being “wounded” by the environment, and responding to wounds. (This makes me wonder what signals, if any, the trees next to or even caught up in PG&E’s power lines might be sending. Nothing pleasant, I would imagine.)

Communication Below Ground

The really sexy topic here is “mycorrhizal networks” (similar, I think, to the “mycelial mat,” see NC here), but first let me follow through on electrical signaling below ground.

Electrical Signals. From Frontiers in Plant Science, “The Integration of Electrical Signals Originating in the Root of Vascular Plants“:

Plants have developed different signaling systems allowing for the integration of environmental cues to coordinate molecular processes associated to both early development and the physiology of the adult plant….. [I]t is well-known that plants have the ability to generate different types of long-range electrical signals in response to different stimuli such as light, temperature variations, wounding, salt stress, or gravitropic stimulation. Presently, it is unclear whether short or long-distance electrical communication in plants is linked to nutrient uptake. This review deals with aspects of sensory input in plant roots and the propagation of discrete signals to the plant body.

“Salt stress”… I can just imagine the trees screaming after the roads get salted in the winter. Or perhaps they are inured/

Mycorrhizal Networks. This is a bit of a grand finale, because Suzanne Simard focuses on that topic and is getting a lot of good press right now. From The New York Times, “The Social Life of Forests” (in one of those horrid mobile-friendly layouts[4], unfortunately):

Underground, trees and fungi form partnerships known as mycorrhizas: Threadlike fungi envelop and fuse with tree roots, helping them extract water and nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen in exchange for some of the carbon-rich sugars the trees make through photosynthesis. Research had demonstrated that mycorrhizas also connected plants to one another and that these associations might be ecologically important, but most scientists had studied them in greenhouses and laboratories, not in the wild. For her doctoral thesis, Simard decided to investigate fungal links between Douglas fir and paper birch in the forests of British Columbia.

Amazingly, the “fungal links” enable what we would, if we were anthropomorphizing, call altruism:

By analyzing the DNA in root tips and tracing the movement of molecules through underground conduits, Simard has discovered that fungal threads link nearly every tree in a forest — even trees of different species. Carbon, water, nutrients, alarm signals and hormones can pass from tree to tree through these subterranean circuits. Resources tend to flow from the oldest and biggest trees to the youngest and smallest.

And of course there is communication:

Chemical alarm signals generated by one tree prepare nearby trees for danger. Seedlings severed from the forest’s underground lifelines are much more likely to die than their networked counterparts. And if a tree is on the brink of death, it sometimes bequeaths a substantial share of its carbon to its neighbors.

Mycorrhizal networks can be enormous:

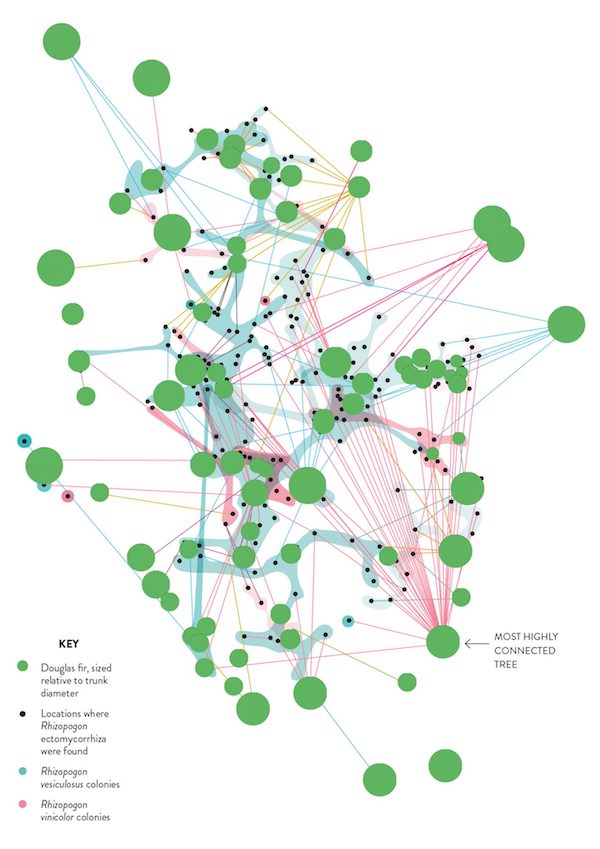

Mycorrhizal networks were abundant in North America’s forests. Most trees were generalists, forming symbioses with dozens to hundreds of fungal species. In one study of six Douglas fir stands measuring about 10,000 square feet each, almost all the trees were connected underground by no more than three degrees of separation; one especially large and old tree was linked to 47 other trees and projected to be connected to at least 250 more; and seedlings that had full access to the fungal network were 26 percent more likely to survive than those that did not.

Here is a network diagram Simard created:

I would argue (as others would not) that we are seeing the typical hub-and-spoke pattern of a scale-free network; the “hub” is the tree at bottom right, labeled “most highly connected,” much as Atlanta is the most highly connected hub airport in the United States. If Mycorrhizal networks are in fact scale-free, that would imply that a hub tree in a forest of thousands of trees would have thousands of connections, and so on.[5] I bet when you walk down the street, looking up at the trees, you never imagined they were all connected and communicating with each other!

Conclusion

I did promise some woo woo — by which I mean material that a Forestry Department focused on yield might have a hard time getting its collective head around — and here, from another Simard article, it is. From Memory and Learning in Plants (PDF), “Mycorrhizal Networks Facilitate Tree Communication, Learning, and Memory.” I will quote the whole abstract, underlining the woo parts:

Mycorrhizal fungal networks linking the roots of trees in forests are increasingly recognized to facilitate inter-tree communication via resource, defense, and kin recognition signaling and thereby influence the sophisticated behavior of neighbors. These tree behaviors have cognitive qualities, including capabilities in perception, learning, and memory, and they influence plant traits indicative of fitness. Here, I present evidence that the topology of mycorrhizal networks is similar to neural networks, with scale-free patterns and small-world properties that are correlated with local and global efficiencies important in intelligence. Moreover, the multiple exploration strategies of interconnecting fungal species have parallels with crystallized and fluid intelligence that are important in memory-based learning. The biochemical signals that transmit between trees through the fungal linkages are thought to provide resource subsidies to receivers, particularly among regenerating seedlings, and some of these signals appear to have similarities with neurotransmitters. I provide examples of neighboring tree behavioral, learning, and memory responses facilitated by communication through mycorrhizal networks, including, respectively, (1) enhanced understory seedling survival, growth, nutrition, and mycorrhization, (2) increased defense chemistry and kin selection, and (3) collective memory-based interactions among trees, fungi, salmon, bears, and people that enhance the health of the whole forest ecosystem. Viewing this evidence through the lens of tree cognition, microbiome collaborations, and forest intelligence may contribute to a more holistic approach to studying ecosystems and a greater human empathy and caring for the health of our forests.

“The forest is the computer,” then, as Sun did not quite say. (I should pause to say that I saw Avatar during a long-haul and quite liked it, especially the “neural queue” concept). So if there is such a thing as “tree cognition,” and there is such a thing as “forest intelligence” — not metaphorically, but literally — can we talk to trees? Or talk to a representative tree in a forest? One biologist thinks so. From Quartz, “A biologist believes that trees speak a language we can learn“:

Connection in a network, [biologist George David Haskell] says, necessitates communication and breeds languages; understanding that nature is a network is the first step in hearing trees talk.

For the average global citizen, living far from the forest, that probably seems abstract to the point of absurdity. Haskell points readers to the Amazon rainforest in Ecuador for practical guidance. To the Waorani people living there, nature’s networked character and the idea of communication among all living things seems obvious. In fact, the relationships between trees and other lifeforms are reflected in Waorani language.

In Waorani, things are described not only by their general type, but also by the other beings surrounding them[6]. So, for example, any one ceibo tree isn’t a “ceibo tree” but is “the ivy-wrapped ceibo,” and another is “the mossy ceibo with black mushrooms.” In fact, anthropologists trying to classify and translate Waorani words into English struggle because, Haskell writes, “when pressed by interviewers, Waorani ‘could not bring themselves’ to give individual names for what Westerners call ‘tree species’ without describing ecological context such as the composition of the surrounding vegetation.”

Because they relate to the trees as live beings with intimate ties to surrounding people and other creatures, the Waorani aren’t alarmed by the notion that a tree might scream when cut, or surprised that harming a tree should cause trouble for humans. The lesson city-dwellers should take from the Waorani, Haskell says, is that “dogmas of separation fragment the community of life; they wall humans in a lonely room. We must ask the question: ‘can we find an ethic of full earthly belonging?'”

I am all for “greater human empathy and caring” and “an ethic of full earthly belonging,” but I would like to know if anyone has ever, literally, tried to talk to a tree. Was it successful? How would one know? How would the communication take place? What could we say that would be of interest to a tree? More nutrients? No wounding? It sounds like a lifetime project, possibly best conducted by a forest monk. Of course, this is the NC commentariat; perhaps we have a reader who has talked to trees already. Hello? Are you out there?

NOTES

[1] The early research on this topic was apparently pretty sketchy, and “The Secret Life of Plants” didn’t help. From Quanta: “The first few “talking tree” papers quickly were shot down as statistically flawed or too artificial, irrelevant to the real-world war between plants and bugs. Research ground to a halt. But the science of plant communication is now staging a comeback. Rigorous, carefully controlled experiments are overcoming those early criticisms with repeated testing in labs, forests and fields.”

[2] Though I am not at all sure trees would think of themselves that way. How Ents came to walk has always been a sticking point for me in Lord of The Rings. What about their roots?

[3] An example of a VOC is Limonene, a major component of pine resin and orange peel scents. (I had a simple mental model of one VOC, one scent, but things aren’t so simple.)

[4] Whichever fool picked 500 for a font-weight also made the article difficult to read in Safari’s Reader View. Acres and acres of bold, ffs.

[5] I am assuming the hubs are trees and not fungi.

[6] That is, by their positions within a network.

I recently started apologize to trees before trimming their limbs. No idea if they hear me, but it makes me feel better.

If I get close enough to a tree to photograph it exclusive of its environment, and especially if the tree is down with roots exposed, I always pay my respects just as I would to any other creature. But then I’ve always been the courteous type.

I’ve been talking to trees since I was a small boy.

I’ve not read much Derrick Jensen, but I saw him give a book talk ~20 years ago and he talked about literally talking with trees. He brings it up in this interview

Along the Aviation bike trail in Tucson, there is Slim’s confidante. Yup, it’s a tree. I’ve been having heart-to-hearts with it since 2013.

The ritual is the same. I apply my brakes, stop the bike, and say, “Me again. And then I get off the bike, lean it against the sound-absorbing wall next to the tree. (It’s there to absorb sound from the Aviation Parkway here in Tucson.)

I talk to this tree for as long I feel the need.

When I’m done, I say “Later!” and get back on the bike.

Yes, I talk to trees (sometimes) and feel that they communicate. Not necessarily with me personally, but in general. One winter day some years ago I ran outside in an icestorm to hug and comfort the huge maple out front and all the trees who could hear(?) me. I had the strong feeling and deeply believe they were afraid of the storm and screaming. Their fear shook me to my roots.

In one of Paul Stamets’s books ( he is a mycologist), I remember reading a chapter where he talks about taking some psilocybin mushroom and experiencing a lot of cross-species information-transfer. He reported feeling that the mushroom inside his head was an interspecies-translator allowing him to “communionicate” with the forest-load of trees and etc.

I think it was THIS book . . .

https://fungi.com/collections/books-by-paul-stamets/products/psilocybin-mushrooms-of-the-world

I’ve seldom tried to talk to trees, but I have spent plenty of time listening. It’s almost always something about the weather.

I’m also reminded of Jack Handy’s little musing:

“If trees could scream, would we be so cavalier about cutting them down? We might, if they screamed all the time, for no good reason.”

Its uncommon for Giant Sequoias to be by their lonesome, almost always in a social group, and they’ve had a thousand or a few thousand years to get to know one another, combined with shallow root systems that spread out-not so much down, which leads me to believe there’s a symbiotic relationship going on with all that root-y tooty going on, but who is male and female is a bit of a mystery.

I guess i’ve spent maybe 15 nights sleeping in ones where a fire came in and burned a chamber for me to slumber. I’ve had some pretty poignant dreams while in their ensconce, although our communication is more of a silent nature.

Heck – it’s all true. I live in a forest. But don’t kill the messenger lol

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XzugQBkUrZk

“Neurotransmitters (NTs) such as acetylcholine, biogenic amines (dopamine, noradrenaline, adrenaline, histamine), indoleamines [(melatonin (MEL) & serotonin (SER)] have been found not only in mammalians, but also in diverse living organisms–microorganisms to plants. These NTs have emerged as potential signaling molecules in the last decade of investigations in various plant systems. NTs have been found to play important roles in plant life including-organogenesis, flowering, ion permeability, photosynthesis, circadian rhythm, reproduction, fruit ripening, photomorphogenesis, adaptation to environmental changes.”

for examples: https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/pdf/10.4141/P06-034

I’ve worked as a wood sculptor over a lifetime, and my big perception is that a tree is like a crystalized river of time. All natural materials exhibit cosmic character that is very satisfying to work with.

Don’t forget DMT.

My neighbor is threatening to cut down the cottonwood in their side yard. The neighbors are in their seventies; the tree is far older with no sign of die back yet. I pointed out how the canopy of the tree acted as a conference center for birds and squirrels. It’s so large it can accommodate several conversations simultaneously, while the redtail hawks perch on top acting like their oblivious. It is The Tree of Life; it would be a loss to the community.

And that’s what can be seen above ground.

One of the first things we did when we bought this house was spread bags of mushroom compost and topsoil over the yards and plant beds. Every spring when it warms up and there’s a rain shower, great dense clusters of mushrooms sprout up out of the bark. Night crawlers beach themselves on the sidewalk until we walk out to throw them back into the ocean of grass. I consider these signs of a healthy soil and therefore, good news for the trees. There are five of them: ash, crabapple, pear, silver-barked maple, and box elder/maple hybrid. Specimens really, rather than a forest, and they talk to each other through the thick sticky clay. Every few years we have to inject a big dose of iron into the maple or it becomes sclerotic. I’m amazed at the tree’s ability to thrive here on the prairie.

I read a piece on Simard’s research years ago and saw the Ted Talk later. Yes, trees talk to each other. Did it need to be proven? I was a photography major in college. My favorite subject was trees. One morning a housemate needed a ride to class and along the way I introduced him to all the trees on our route. I wasn’t aware I was doing it until he pointed it out. I didn’t know other people didn’t notice, and he didn’t know some people do. Huh.

Towards the moist Eastern side of the Tall Grass Prairie zone, trees would be the natural next step if not for steady prairie fires burn-killing little seedling getting started. And many of the fires were by Indian Nations fire-managers if they saw a lack of natural fires setting in. Or so I have read.

So if you are in the semi-moist side of things, it may not be so surprising.

Talk to trees? I don’t know about talk but communicate definitely. Not only trees but the whole plant kingdom, if we so choose. Most of it is about shutting up long enough to hear/feel them.

They are just watching us and waiting to see if we can get it.

But it ain’t ever gonna be a scientific method kinda thing….although that does have a place.

These are people who have been at it a while:

https://www.findhorn.org/blog/a-findhorn-garden-miracle-love-from-the-leeks/

Here is someone who has been doing her own version of the working-with-nature-entities thing which the Findhornians have been doing.

Machaelle Wright

https://www.perelandra-ltd.com/

and . . . https://www.perelandra-ltd.com/Environment-Gardening-for-Beginners-W5588C736.aspx

Of course lately she’s apparently gone into selling all kinds of stuff. But books she wrote many years ago about what she was doing still seem interesting to me.

https://www.thriftbooks.com/w/behaving-as-if-the-god-in-all-life-mattered_machaelle-small-wright/267949/#edition=2499898&idiq=357148

Selling books about what she has learned is useful. It can dramatically reduce the learning curve.

Communicating with nature doesn’t cost anything. You don’t have to buy anything. Wright generously shares loads of info for free on the Perelandra website.

As a business Perelandra-ltd is pretty unusual in that they do no advertising. Even more unusual is that the business is run as a part of the garden’s research activities–every aspect relies on information direct from nature about how to create balance in the context of an equal working partnership. Every single thing they sell was a suggestion from nature–not an entrepreneurial decision from Wright. She was dismayed when nature first suggested she develop a new set of flower essences, for example. She was happy with the Bach Flower Remedies she’d been using for years.

They don’t even have a sales department. Only customer service. They’ll provide info but won’t attempt to persuade to buy.

The personalised PIC info is remarkable.

Maybe us humans are not built right to understand trees and what is going on with them. You may have individuals that while walking through a forest can pick up the visual clues of what is happening with trees and perhaps even pick up by smell some of the signals that trees are giving off but that is about it. There was a scene in the 2014 film “Lucy” that indicted that we would have to evolve more in order to see trees as they really are-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8CD506G0WkA (26 seconds)

It has been well over 25 years since I’ve read The Celestine Prophecy, but the part that resonated the most was sharing energy with trees and communicating through that energy. Right after I read The Celestine Prophecy, I started reading Gerry Spence’s From Freedom to Slavery. Spence discusses defending a grove of trees in court. That was a good month or two of reading! A few years ago, I think either Lambert or Yves shared an article about a river in India that had standing in court, which made me think Gerry Spence would appreciate that legal case/situation. I should mention that I bet a lot of NC readers would appreciate From Freedom the Slavery if you haven’t already read it. Quick read too.

One of my favorite topics!

Researchers also recently identified that kauri trees will send resources (sap) to nearby stumps in order to keep the stumps “alive”. In return, the healthy tree can use the stumps root system to expand its ability to take up water.

https://www.cell.com/iscience/fulltext/S2589-0042(19)30146-4?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS2589004219301464%3Fshowall%3Dtrue

If we could understand the wants and needs of trees, would it surprise us?

These trees that are interconnected thru their roots- are they interconnected as lovers? Brothers and sisters? Or maybe as slave owner and slave? Conquerers and the conquered?

Do the trees see each other as friends and allies? Or as competitors?

And how about the other plants? Shrubs? Are they seen as allies or competitors and invaders?

Are the mighty oaks sad to see the basswood cut down but happy when the buckthorn is cut back?

I have about an acre of woods that surrounds my 4/10ths acre organic garden (which I lease). I have plans to go thru the timber and remove the “undesirables” to give the “desirables” an advantage. Oaks are protected, buckthorn and silver maple and cotton woods will go. Basswoods and elm are on the cusp depending on size and location. Any recognizable fruit trees stay. Space will be made for some (new) evergreens for the avian friends.

But which tree does the owl hoot from every afternoon? I think a basswood and that one needs to stay.

I would like the end result to feel more like “oak savanna”, open and airy, no under brush, and capable of being mowed short enough that one can easily gather acorns.

I think the mighty oaks will be happy with my plan. But now I guess I need to ask?

Does anyone else have the song “Trees” by Rush going thru their head right now?

Has anyone else watched Buckin Billy Ray (you tube) go visit the largest (known)fir tree? I think he might have some communication with the trees?

Peace.

It seems to me that people who believe that individuality is more important than communal sharing would see the relationships of trees in those ways too. We humans sometimes forget that trees ARE living things after all. I wonder too how much sentience the wood in a house would still have.

One thing I do know for sure is that I have a most wonderful sense of peace and goodness when I spend time amongst a group of trees.

I’m not sure why anyone else hasn’t mentioned this book.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Overstory

It’s deftly written in a way that artfully interlaces arboreal revelations in the same way that Melville did with whaling in “Moby Dick.”

I’ve now lived long enough to see thumb-diameter native Sycamores I planted grow to 2′ diameters. They abut surrounding groves of Quericus Agrifolia, Coastal Live Oaks, in a riparian setting.

that’s funny, I linked to a videogame story yesterday that drew attention to this book, Underland by Robert MacFarlane. For a second I was wondering if we had in mind the same book. From the same publisher at any rate! It’s non-fiction though. Apparently very good.

I’m just finishing The Overstory, it’s fantastic. After reading it you’ll never think about trees the same way again.

I am wondering what ‘talking to a tree’ would mean in the context of a mycorrhizal network like the one described in the article. The immediate problem is that we don’t possess the necessary organs or connections to transmit or receive messages in their ‘language.’ So we’d need some kind of translation device that converted our language into biochemical signals via the network and vice versa.

However, it’s quite likely that it would be impossible to communicate with them in that language without lying, because it presupposes that we are some kind of plant or tree wired in via the network, and they don’t have ‘words’ for what we are. We might learn how to say “I am a young and growing sapling, please send resources” or “I am a dying tree, have my carbon” but obviously neither of those two things are true.

A less ambitious question, which might provide a stepping stone to an answer, would be whether the network of plants is capable of learning, categorizing and adapting to new things. We could try wiring something into the network that isn’t a tree or plant and that sends signals that are different from any known ones, but are still simple and predictably repeatable for a given set of conditions. We could then see how the network handles it, and what new interactions arise (if any).

That is actually one of quite fundamental problems that some people are looking at – not in the sense of “talking to trees”, but more in the sense of aliens more generally, i.e. someone who has an entirely different frame of reference in respect to “their” reality.

Lot’s of SF written on that, but I believe some serious work too.

That’s exactly the challenge Machaelle Small Wright experienced after stating her intent to learn from nature.

Over years nature helped her understand nature’s perspective, and together they developed communication tools that could be used by anyone, no special sensitivity required.

It’s practical. I use it on a daily basis. If I want to know if a plant needs water, fertilising, repotting, relocation I just ask. I provide my context (eg my goal for a garden or piece of land will not be the same as someone else’s) and nature then helps me take action towards my goal that is balanced from nature’s perspective. Eg, nature might recommend something very different from what I might have considered.

My earliest memory is of my grandmother in New Zealand, who was part maori, carrying me as an infant into the bush as we call it, setting me down under a tree and disappearing, leaving me alone for quite a while. I can clearly remember hearing a bellbird, not being frightened at all, just sitting with the trees. Ever since they have been part of my life, and I’ve suffered when they are cut down. I don’t talk to them though, but I am so grateful she did that, gave me that experience. I don’t know if that was a native practice back then – it could have been. She was raised maori and knew the language. She’d had a very hard life, we learned later, but she was always happy, the happiest person I’ve ever known.

A friend who lives in central Alberta has an apple tree on their front lawn. Whenever I walk by it in winter, I compliment it on its ability to survive Alberta winter. It does survive and each autumn it produces extremely tasty apples.

I don’t know if it hears me, but anything that can sit naked outside in night after night of sub-zero temperatures and survive deserves praise.

Learning directly from nature with 2-way communication has been the focus of Machaelle Small Wright for over 40 years at Perelandra Nature Research Center in Virginia. Her books share how anyone who wants can do the same. She shares various tools for communicating.

This is something I’ve applied since 1992 when a friend gave me one of her books for my birthday. It’s tremendously practical, not to mention inspiring and sometimes funny, and often unexpected.

In relation to trees on my own property I ask about things like pruning (whether, when, how much), if a tree should be removed, whether new trees should be added, what kind, and where.

Nature can give extremely precise information. Nature seems to appreciate questions based on action.

If trees could talk, I wonder what they would say about the anti-tree problems discussed in this blog right here? . . . . https://witsendnj.blogspot.com/p/basic-premise.html

I add my thanks for this post to those of others. And I will confess that one of the first things I thought of was the David Brin book The Uplift War . . . and the way Terrans worked with, or at least via, the ecosystem of the wounded planet they’d been awarded custody of against a clan of alien species trying to destroy them both — the Terran clan and the surviving native lifeforms, animal and plant.

It’s hardly a perfect example, I admit — though, in the in-universe context, perhaps not as colonialist as it may sound. I mention it here primarily for the methods of chemical communication shown in the book . . . some of them might be “translatable” to more direct communication with plants. Here’s a chapter describing one key mechanism.

Thank you! Lovely synthesis.

What a wondrous post, Lambert! For me, your best yet. The science is fascinating, although I can’t say I’m surprised.

My first conversation with a tree did not go well. It was near Sedona in 1990, during a tense cross-country trip from Washington, D.C., to the Monterey Bay region. We were driving a 14-foot U-Haul truck carrying everything I owned, with my sub-compact car in tow — “we” being myself and the little weasel of a friend of my then-partner, who’d flown ahead to our new home. As part of the deal, we agreed to a detour to Phoenix to visit weasel’s relatives.

I had no idea what lay ahead of me. I’d quit my job as a reporter covering environmental issues for a specialized business newsletter. It paid well, but I’d started having a nagging feeling that all the effort I was putting into exposing government corruption was actually helping the fossil fuel industry lobby more effectively against regulation. My detailed insider reports about environmental advocacy were helping the industry prepare better counterarguments against the “tree-huggers.” Meanwhile, I’d been reading a lot of New Age-y stuff, experimenting with aromatherapy, Bach flower remedies, and such. Somewhere along the line, I encountered the energy vortex theory of Sedona.

Heading south from Flagstaff on I-17, we pulled into a rest stop, or maybe it was a state park, I forget. I desperately needed to be alone and took a walk along a path into some trees. I’d seen the turnoff to Sedona and figured we must be near enough to be in the “zone.” Whether we were or weren’t, there was an energy in that place, and I had a spontaneous urge to hug a tree. I mean, why were the environmentalists called “tree-huggers” if no one actually put their arms around a tree? And I loved trees. In a parlor game three years earlier, guests were asked,” If you could be any animal, what would it be?” I said I wouldn’t be an animal, I’d be a maple tree.

Although I don’t remember what kind of trees surrounded that path near the interstate, I have a clear memory of approaching a tree, laying my head against the trunk, and just listening. Maybe I would hear some words of wisdom or comfort, or simply feel the calm of being out in the open, in the natural world.

The tree had some words for me, all right. But first, it sent an army of ants to repel the intruder. Before I realized what was happening, they were crawling across my forehead and up into my armpit. As I was shaking them off, the tree gave me an unmistakable piece of its mind: “You come driving through here, like millions of tourists, in a truck that pumps out fumes that choke trees, and you think hugging me is going to make me your friend? Get back in your pollution machine and get the [family blog] away from me.”

In the intervening 30 years, I’ve conversed with many plants, with more deference and humility. I don’t know if we can ever be fluent in their language, but I feel like I’m getting the hang of it. It’s a different way of communicating. Since last fall, I’ve had my very own treefriend in my garden. Well, actually, it’s a shrub, Cornus sericea — red osier or red twig dogwood. I noticed it in the orphan plant section at the home improvement store garden center (the place Lambert says you should never shop) and checked its ID tag. Immediately, it started telling me that it was in life-threatening distress and desperately needed water. It didn’t look dry or wilted, but I took it at its word. As it so happened, I had a suitably soggy spot at the far end of the garden that it took to right away.

Although I talk to all of my plants, I’ve never named them. Dogwood wanted a name. Its flowering season having been interrupted by the cruel treatment at the orphanage, it resumed producing tiny star-shaped flowers once it was properly cared for. What would you name a dogwood with stars? Sirius, of course! I wasn’t in my garden as much this past summer as the year before, but most days I greeted Sirius and we “chatted.” I can’t say how the plant experienced it, but I experienced it — as I have with other plants, as well as some animal — as pictures in my mind. Sirius sent me images, and my thoughts reshaped them and sent them back. And so forth.

There’s lots more I could write, and I do want to address a couple of other points in the post. However, this comment is already way over the legal limit, so I’ll stop here for now.

Thanks again for this, Lambert — very thought-provoking.

I too often experience getting a “picture” when talking to nature. Sometimes it feels like a “thought package” I can put into words, like that dramatic first experience you had.

Other times I just get yes/no responses to specific questions by muscle testing (after first consciously connecting to nature–as simple as “hey nature–does this plant need water now?” If yes–“how much? As much as 1/4 cup? 1/2 cup?” Etc).

“Thought package” — wonderfully descriptive phrase. I can picture it! ;-)

Thanks for pointing out that mental pictures are but one way of communicating directly with the natural world. Since the topic at hand was talking to trees, and the primary means for me has been the exchange of mental pictures (again, with the caveat that I don’t know how the tree experiences these exchanges), that was the first thing that came to mind. I would think that any means of “reading” energy would work, whether it’s applied kinesiology (which I just discovered is also called manual muscle testing, or MMT; how funny is that?), color and light, pictograms, numbers, Tarot symbols — whatever speaks to you. Sometimes, as I am reminded by vw’s comment below (2/2, 6:05), the messenger might also be the message. I regularly encounter the latter, but never more clearly than when I’m in a gardening groove. And who knows? Maybe that “groove” is my tapping into the various chemical signals zinging back and forth all around me, with my own thrown into the mix.

I’m looking forward to Part 2.

What I very much like about this post is the effort to inform on stuff that is widely ignored by us in general. The ability of plants and trees to sense the environment, react to stimuli and send signals (communicate) with other organisms in the environment. Of particular interest is that the habitats are not made just by the individuals growing more or less closely but that these build communities with all members (vegetal, fungal, animal, bacterial) implicated and connected in various ways (of which we surely ignore many if not most community rules).

Some friends of mine work in plant genetics and physiology and their thesis always start with the same standard phrase: Plants are sessile organisms and have developed ways of sensing and communicating with their environment… (we laugh about this). Some of them work in the physiology of roots, which has the particular challenge that they have to mimic the natural darkness of the environment while allowing the direct observation of phenomena. It is also true that we also tend to forget the sheer importance of the roots, their soil communities, their vast biomass and their importance in the formation and recycling of organic matter.

So, this was a nice an entertaining effort.

A slightly off-topic. Yesterday’s episode of the Infinite Monkey cage podcast was on Science of cooking.

One of the guests was talking about tea there, specificaly how a leaf torn from a tea-bush behaves over tim in response to the stimuli (of being torn, and what happens afterwards), and how that affects what sort of tea can be done from the leaf.

IIRC, I read somewhere that the young tea leaves synthetise caffeine based on how much they are damaged, the assumption (of the plant) being that more damage = not just a random damage but insect, hence more caffeine (which works as a natural insecticide)

Here is a link about diagrams of plant roots from the most recent Water Cooler thread. Put here to be easier to find into the future.

https://images.wur.nl/digital/collection/coll13/search/page/1?fbclid=IwAR2CTUTvpUnLlEg34ZqkywEHFELQOBx0HEKKMepuj94VSo5ouI0WiBmntlk

In ancient Irish folklore, there are variations on the notion that making a musical instrument such as a harp from a tree allows that tree to talk to us. There are stories of a tree being told a secret, then when the limb of the tree is turned into a harp it unexpectedly coughs up the secret during a music recital. Like so many Irish stories, there is probably an earthier pagan original which was polished up for Christian days.

Of course, the notion that trees have sacred knowledge that they communicate to us via the fungi growing around them is as old as shamanism. It is something that most organised religions have done their very best to suppress.

I’m sure some Science Fiction writer has got there before me, but I’ve idly wondered if the reason we seem to be alone in the universe despite habitable plants being highly abundant, is that the natural direction of evolution is for highly integrated conscious self managing ecosystems, which prevent any one species getting dominant. So the universe could be full of integrated intelligence, its just that it never occurred to any of those beings to built space craft or mobile phones – just on earth something went haywire and one species of aggressive ape managed to destroy a nice stable balance.

This is actually very common across at least European folklore. In Slavic nations it’s usually flute or violin (telling the secret). Plenty offolk songs with that theme.

If you want SF/F on forests, Le Guin has World for Word is Forest (which many people believe was copied into Avatar), and you could argue that Mythago cycle is sort of something like that.

Most humans have no idea how much trees help us and how important they are.

I was once a buyer and seller of fine old guitars from the pre WWII era, and the period from the late 20s to the mid 40s is generally regarded as the golden age of acoustic steel-string guitars. Back when I was a dealer I never thought much about the trees that gave their lives so that we could make music from the wood, but I certainly appreciated the sound.

Brazilian rosewood is now a protected species and the import and export of it is strictly controlled. Honduran mahogany was another common guitar wood that is now scarce and expensive. Adirondack “red” spruce for top wood (the pale soundboard of a guitar) was plentiful at one time but logging and acid rain decimated the species starting in the late 40s but it is now thankfully making a comeback and is being used again.

Alternatives to these woods have been found for modern guitar-making, but now some of those species are also becoming threatened, such as Madagascar rosewood and others. Many of these woods were originally frittered away on laminates to make furniture look pretty, but at least a lot of the guitars are still around.

In Doonesbury, Zonker would talk to his plants; “Ed” the geranium would recite Gunga Din for him.

Here is the cartoon:

https://www.gocomics.com/doonesbury/2014/05/26

Hmm

I think the problem has it’s roots in the biblical injunction –

“Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; rule over the fish of the sea and the birds of the air and every creature that crawls upon the earth.” Genesis 9:1″

Our forefathers who populated the New England forests spoke of the Forest Primeval.

The forest we subdued with fire and ax.

Of course trees and all of the beings of our world talks to us, however we fail to listen. It speaks slowly with long silences.

When my boy was young the favorite way to stop his fussing was to place him in a laundry basket (suitably cushioned of course) and place the laundry basket beneath a red cedar where the hoot owls nested. In a few minutes he was quite and calm. Was the cedar talking to him ? I do not know however being outside shore seemed to help.

Lambert, apologies if you already mentioned this but I quickly went though the article and didn’t see it. You guys have been posting too much good stuff lately and I can’t read it all as thoroughly as I might like. Anyway, this book looks like it’s right up your alley – The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate.

It’s written by a long time forester at a popular science level, and quite good if you’re into stuff like mycorrhizal networks!

It’s highly unlikely that we can communicate with trees as individuals, being the short-lived creatures we are, and presumably having a completely different time horizon and speed. Our society may. There are reasons to hope, after all Europe has reversed much of its deforestation in the last century.

Tolkien captured this in describing the completely different sense of time the Ents have compared to Hobbits.

I’ll add one more since I didn’t see it posted.

Maria Popova: Hermann Hesse on What Trees Teach Us About Belonging and Life

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/hermann-hesse-on-what-trees-teach-us-about-belonging-and-life?utm_source=pocket-newtab

I’m a tree hugger, not so much a tree talker. But one thing – I plant about a thousand trees a year in two restoration woodlots (cut some down too for firewood and lumber) – and I find they always do better when I plant them close to a stump, particularly a stump of the same or related species. I figure the new tree hooks into the micorhyzal (spelling?) network of the old tree and this gives it a leg up.

More philosophically: Is tactile communication talking? This applies to human communication also – tactile communication is mediated by living energy – think of the buzz you feel when you connect physically with another person – I think it works for trees also. However, trees operate on their own time so imho it helps to slow yourself down to something approximating tree time.

Late to the thread – tree time, I guess! – so hope this reaches a few eyes!

How encouraging to see that this post has a shelf life longer than 24 hours! “Tree time,” or simply a normal human response time for such a thought-provoking post? Maybe it only seems like “tree time” if your idea of normal is churning out comments in less time than it takes to scramble an egg?

Anyway divadab, thank you for an insightful “late” addition to the conversation. Touch definitely is a means of communicating directly with non-human beings, including plants. I’m sorry I didn’t think to mention it in my reply above to TheCatSaid or, for that matter, in my original comment (2/2@2:23 a.m.). In fact, my relationship with my new treefriend included a lot of touching, almost like petting a cat or dog. There was the initial job of painstakingly separating potbound roots — the source of the plant’s distress and inability to suck up sufficient water. A lot of energy was exchanged during the time it took to patiently untangle the roots — stressful for the shrub, even though it ultimately saved its life.

Lambert, this is a most wonderful article. Thanks for taking the time to research and present your findings. I will always look at trees in a new way because I read what you have written.

Wellie, answering this question might be a good way to get a handle on ESP as well as some of the mysteries of evolution. For instance, if we put a tree and a person in a room and monitored their respiration, their chemicals, etc. over time and correlated the two we could see if they were chemically responding to one another. Which is, I submit, talking. And we could use that same monitoring technique to monitor siblings to see how they talk to each other without speaking, how they respond as if by ESP. That familial long term research could be translated into germ cell adaptations, mutations over one or two generations if we wanted to actually be patient about it. Then on the other hand, the answer to your question is simply, Why yes we can learn to talk to trees. I wonder if we can determine if trees are as crazy as we are. I’m pretty sure we’ll take that a prize.

Recently two large trees on my father’s land were cut down (both were leaning dangerously towards the roof). I made sure to place a hand on both of them and “mind-beam” a goodbye, and a thank you for all they’d done for our land. Even though I think the decision to take them out was correct, the property itself seems “lesser” now. Hopefully there will be a side-benefit of more sun for the garden.

Reading this, I remembered I once had a “friend” in second grade – a little bushy weed bravely poking through a crack in the asphalt in the middle of the school playground. I used to have long conversations with it – it didn’t “talk” back per se, but it was a good listener. I used to imagine it getting bigger and stronger and breaking up the asphalt properly, and making that rather bleak landscape into something greener and nicer. I moved schools the next year, and the playground was better kept – no more friends to follow.

I would say “it’s probably dead now” but I have a gut feeling that sort of weed was tougher than that. I expect they repaved the asphalt, but I bet some of its children are regrowing around the edges. What was it they said? Life finds a way? :)

Good stuff here, Lambert — reminds me of when my colleague who teaches Biology told me that one of the reasons white pines (Pinus strobus) do so well in sandy, nutrient-poor soil is that the fungi in their root systems will actually eat insects and other small invertebrates.

Give a whole new meaning to the Maine state flag with its huge white pine, and the state motto (“DIRIGO”, I lead).