Yves here. Hubert continues his deep dive into why and how airlines are fighting the operational changes needed to get them on a sounder footing. And par for the course, airplanes are now falling apart in the sky! Well just some United and JAL Boeing 777s, but still….they symbolism is arresting.

By Hubert Horan, who has 40 years of experience in the management and regulation of transportation companies (primarily airlines). Horan currently has no financial links with any airlines or other industry participants

Readers who would like a comprehensive overview of the aviation issues discussed in this series over the last year should take a look at my new article, The Airline Industry after Covid-19: Value Extraction or Recovery? just published at American Affairs.

That article was commissioned after my September video interview with Izabella Kaminska of the Financial Times. [1] Izabella asked whether there wasn’t some glimmer of good news or hopeful future prospects. Wasn’t there still some way to reduce the economic value that was being destroyed? Short answer was no, but the new article lays out a more complete explanation than can be provided in a blogcast or posts like this.

While the magnitude of the losses and cash drains is unprecedented, the bigger issue is that the obstacles to a restoring the most possible service and employment are overwhelming. The new article explains the origins of those obstacles, and how they became powerfully entrenched.

Ugly Full Year 2020 Financial Results Reported

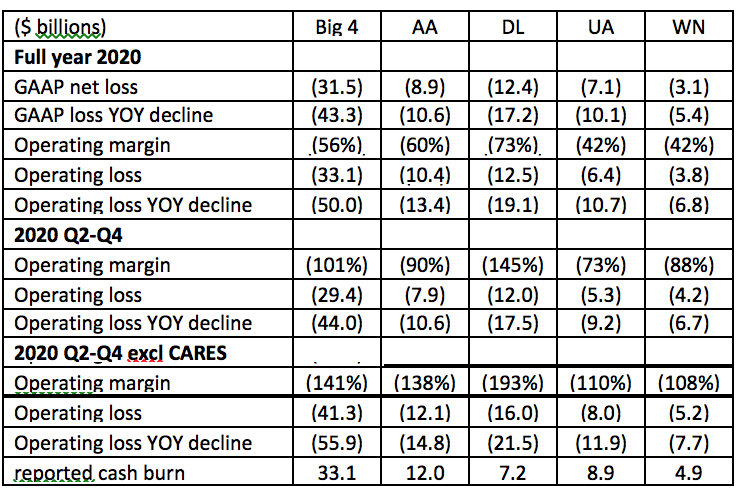

The Big 4 airlines (American, Delta, United and Southwest, that account for 86% of the industry) had full year 2020 GAAP net losses of over $31 billion, and operating losses of over $33 billion. Smaller carriers such as Alaska, JetBlue and Hawaiian have reported additional losses of over $3 billion. The overall aviation ecosystem (including airports, regional feeder airlines, internet travel services and maintenance/ground handling suppliers) lost billions more.

Most of these losses occurred in the last three quarters when the Big 4 had an operating margin of negative 101% and reported burned over $33 billion in cash. Underlying economics are worse because these carriers report a portion of the CARES Act subsides as operating income. Excluding these gifts from taxpayers, the Big 4 had an April-December operating loss of $44 billion ($50 billion worse than the same period in 2019) and an operating margin of negative 141%.

As the previous five parts of this series have emphasized, the central problem is the industry’s inability to reduce operating expenses (full year 2020 down $50 billion versus full year 2019) anywhere remotely close to the decline in operating revenues (down $100 billion year-over-year). Nothing in the carriers’ fourth quarter results indicated any meaningful progress towards closing the cost/revenue gap. Southwest’s fourth quarter results said that revenue performance would need to double just to reach cash flow breakeven (not profitability), the exact same warning they had issued six months ago. [2Taxpayer Subsidies to Sustain Equity Values Reach $65 Billion, but Aren’t Enough

Since the original $50 billion in subsidies provided last March by the CARES Act did nothing to improve the industry’s terrible economics, the Big 4 carriers spent most of the summer and fall lobbying for additional funding. In December Congress provided an additional $15 billion.

As with half of the March subsides, this was packaged as “payroll support.” 38,000 staff who had been laid off in October when the March subsides expired were rehired through March 2021 even though there was no work for any of them to do. While some of this money ended up in the pockets of United pilots, the claim that the central objective of these subsidies was unemployment reduction isn’t credible. It requires believing that the same Congress that was fighting tooth and nail to prevent relief for other individuals from exceeding $600 were willing to pay $400,000 per person to keep a narrow set of airline employees employed for just four months.

As discussed previously in this series, the industry’s primary objective throughout the pandemic has been to preserve the value of equity and the ownership/senior management status quo. Over 100% of the Legacy carriers’ (AA/UA/DL) year end liquidity comes from the subsidies and funds raised from capital markets after the Congressional subsidies signaled that these airlines were Too Big To Fail.

Without these subsidies, these carriers would not have been able to sustain operations and equity-holders would have been wiped out. “Saving jobs” was a PR smokescreen. The Congressional subsidies were designed to ensure that existing shareholders received 100% of the gains from any post-pandemic equity appreciation, and that the taxpayers who made it possible got none.

But $65 billion is not enough to protect current airline owners if major cash drains continue throughout most (or all of) 2021, and the Big 4 have already started lobbying for a third round of subsidies while warning that major layoffs will resume when the second round subsidies expire at the end of March. The Legacy carriers have already mortgaged the vast majority of assets that could possibly serve as collateral and are unlikely to be able to raise significant new funding from capital markets until after a major revenue recovery is clearly underway. They are “zombie companies” unable to repay their financial obligations out of current earnings.[3]

No Light at End of the Tunnel

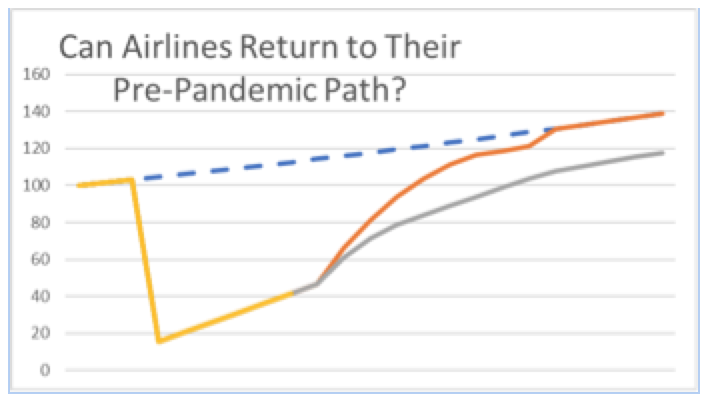

From the outset this series has pointed out that industry expectations for a rapid and complete return to pre-pandemic revenue levels had no basis in reality. Those narratives falsely assumed that the recovery of business and international demand that is critical to profitability would begin within a few months, and that once a recovery was underway, revenues would snap-back to their 2019 levels within 12-18 months. [4] When the first reports of vaccine effectiveness came out last fall, hopes for a rapid snap-back resurfaced, with the starting point repegged for the first or perhaps the second quarter of 2021.

Industry insiders are finally beginning to recognize the powerful linkage between border closures and the collapse of business travel. As one observer noted, “the countries that have been really good at suppressing the virus have done it by killing international aviation.” [5] Thus the industry’s recovery cannot begin until the spread of the virus had been so widely suppressed that businesses could start to reconsider travel bans and governments could end border closures without fears of triggering new case load spikes.

Myriad vaccine issues and the spread of virus mutations could push back the starting point of any recovery (and the end of the industry’s ugly cash drains) into 2022. Aside from granting these four companies unlimited access to the US Treasury, there has been no public discussion as to how continuing drains might be funded, and how a major industry collapse could be avoided in any less-than-best-case virus suppression scenario.

Bankruptcy filings last summer could have easily stopped the hemorrhaging but it may now be too late for bankruptcy restructuring to work. Successful bankruptcy reorganizations require a significant amount of cash, but tens of billions in cash has already been burned and asset values have eroded waiting for a revenue rebound that wasn’t going to happen. Past airline bankruptcies were painful but never had to deal with a cost/revenue gap remotely as large as what these airlines face today and never involved lengthy delays while airlines hoped that their financial problems would magically disappear . [6]

There are also serious concerns about the second part of the recovery equation—the restoration of some degree of financial viability and stability after the recovery begins. For the first time industry insiders have begun openly acknowledging that demand won’t quickly snap back to pre-pandemic levels, and business travel may remain seriously reduced for a very long time, if not permanently. [7] But there are numerous other factors, that could also depress post-pandemic demand. Even after a real revenue recovery starts, the industry will still be dealing with the worst demand, efficiency and liquidity levels it has ever faced. Higher fares could significantly hurt the recovery as could external factors such as “long covid” and ongoing recurrences of smaller outbreaks. International travel could remain highly restricted for years until the virus has been eradicated globally.

Significant Risks of Post-Pandemic Predatory Value Extraction

In the 20thcentury, the airline industry not only survived multiple crises, but always emerged stronger. Unfortunately, both the general ability to drive ongoing efficiency improvements and the specific ability to use efficiency gains to accelerate crisis recovery have been lost. Industry productivity has been declining for 20 years, especially in domestic markets and for the legacy carriers. In the current crisis the industry has categorically ruled out any of the restructuring efforts used in the past to fix the problems that created crises and to liquidate the least competitive capacity.

Instead of responding to crises with efficiency-enhancing innovations, 21stcentury industry financial improvements have come from predatory value extraction, especially from exploiting the artificial market power over consumers, employees and suppliers made possible by extreme levels of industry concentration. [8] Innovation and competition is hard, mergers and price increases and lobbying to protect the ownership/management status quo are much easier. Returns to airline investors come from reducing the contribution of the industry to the overall economy.

Even though the industry recovery has yet to begin, it is important to understand why it will inevitably focus on further reductions in competition and other forms of increased predatory value extraction. As KLM CEO Pieter Elbers pointed out months ago, “every big crisis in the industry so far has led to further consolidation. After pure crisis management is behind us, somewhere in the middle of next year, there is going to be a stage when consolidation and further collaboration in the industry will take place.” [9]

Efforts are already underway to merge Korean and Asiana, and a similar Japan Air Lines-All Nippon merger has been proposed. These would effectively eliminate meaningful competition in Korea and Japan, and significantly reduce it in many Asia-Pacific markets. Stock speculators have bid up the prices of the second-tier US airlines (Jetblue, Alaska, Hawaiian) in the expectation that the Big 4 will try to acquire them.

The industry will also pursue ways to reduce competition without formal mergers. Qantas and JAL have proposed “strengthening” their existing code alliance (e.g. increasing their ability to collude on capacity and pricing) even though they already have an 86% share of the Japan-Australia market; and a JAL-ANA merger would push this closer to 100%. [10] On the last day of the Trump Administration DOT Secretary Elaine Chao approved cooperation between American and JetBlue, the first ever application for airline collusion in domestic US markets. [11] Lufthansa, Air France and other large international carriers have demanded that longstanding airport slot “use-it-or-lose-it” rules be abandoned in order to block new competition at their hub airports.

The problem isn’t that the industry might shrink. Given the incredible devastation of international airline demand, it may be that a major portion of 2019 capacity can never return, and that some previously viable airlines need to be liquidated. The problem is that the industry has come to believe that increased consolidation and collusion is the solution to any financial problem it might ever face. If industry revenue declines, the airlines refuse to consider reducing capacity across-the-board while maintaining competition and insist that the only possible option is to reduce the number of competitors.

Even if total capacity shrinks, governments could take a number of simple steps to preserve and protect competition and better balance the interest of airline investors and the interests of consumers, employees, suppliers and the overall economy. Airlines may insist that they cannot attract capital unless new mergers and price collusion are approved but demands to harm consumers in order to improve investor returns should be rejected out of hand.

Merger applicants should be required to demonstrate that they will not increase market power and to produce verifiable evidence of any cost synergy claims. Collusive international alliances and airport slot rules that had been justified by pre-pandemic levels of competition need to be suspended until independent analysis demonstrates they will not reduce competition under post-pandemic conditions. As an example, Delta’s collusive alliance with Korean assumed healthy competition in the Korean market and the existence of multiple other competitive Asia-Pacific alliances (United-Asiana, United-ANA, American-JAL), and all of these alliances should be terminated if any of the mergers being discussed are implemented. Any proposals to allow carriers to coordinate schedules while demand remains severely depressed must have strict termination clauses tied to actual traffic recovery and must not be permitted in any cases where the colluding carriers would have a significant market position.

The underlying problem is that the major 21stcentury reductions in competition that halted productivity growth and crippled the industry’s ability to respond to the current crisis all resulted from proactive government actions designed to help airline investors extract value from the rest of society. When coronavirus hits, Washington immediately responded with massive direct wealth transfers from taxpayers designed to protect existing airline equity holders. We have no evidence suggesting Washington will do anything to protect market competition or overall economic welfare, or take other steps to limit future fare increases, job losses or cuts to the service that cities and industries depend on.

_______________

[1] https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2020/09/10/1599758074000/Alphavid–The-airline-sector-is-in-denial-about-its-imminent-collapse/#comments Direct YouTube link to the video (about 40 minutes): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hzig-gnKWTI#action=share

[2] Kyle Arnold, “Southwest Airlines needs ‘business to double in order to break even,’ CEO says” Dallas Morning News, August 28, 2020

[3] Lisa Lee, America’s Zombie Companies Have Racked Up $1.4 Trillion of Debt, Bloomberg, November 17, 2020

[4] Hubert Horan: The Airline Industry Collapse Part 3 – Recovery Expectations Were Always Dreadfully Wrong, Naked Capitalism, August 4, 2020

[5] Philip Georgiadis and Claire Bushey, Airline industry alarm as vaccine-led recovery hopes take a dive, Financial Times, February 15, 2020

[6] The requirements of a successful bankruptcy—based on the industry’s long experience, and the major difficulties an airline bankruptcy would face after having already suffered a full year of coronavirus losses are discussed in pp. 50-52 and 55-57 of the American Affairs article.

[7] Kevin Michaels, “Why Business Travel Could Change Forever”, Aviation Week and Space Technology, January 18, 2021; Doug Cameron and Eric Morath, “Covid-19’s Blow to Business Travel Is Expected to Last for Years”, Wall Street Journal, January 17, 2021

[8] The data demonstrating these productivity/efficiency trends are shown at pp. 46-49 of the American Affairs article.

[9] Helen Massy-Beresford, Airlines Likely To Need More Government Support, IATA CEO Says, Aviation Week, September 24, 2020

[10] CAPA Centre for Aviation, “COVID-19 crisis strengthens case for JAL-Qantas partnership”, January 6, 2021.

[11] Leah Nylen and Stephanie Beasley, “Approval of American-JetBlue deal draws warnings of rising airfares”, Politico, January 16, 2021

Boeing doesn’t seem to have a good time, does it? Not just the 777 issues, but also a cargo 747 having it’s engine falling apart over Netherlands..

The recent accidents could be coincidence of course, but I wonder if Covid is having an impact on maintenance and usage of engines. There have been a few examples in the past where unusual travel patterns resulted in aircraft being subject to stresses that weren’t accounted for in the original design and specification (short hops between Hawaii islands causing fuselage failure, for example). There has been some hasty retrofitting of aircraft to convert from passenger to cargo.

That was my thoughts. But I have no data or even anecdotes to put it either way.

Easy to say this from the ground….but that Denver 777 did exactly what it was supposed to do—survive an engine catastrophe and make an emergency landing.

777 (its Airbus equivalents) were designed to survive an engine failure over the middle of the Pacific Ocean and return to a safe landing.

Easy to lose among the news sensationalism but by far, it’s safer to travel 100,000 miles via airline than car or US train.

It’s nice to see that this time the system worked! (compare/contrast to TX or CA electricity grids)

But it is safer to take 100,000 journeys by car than by airline.

Fatalities per 100k miles is a chosen airline industry measure to minimise perception of risk.

The natural question to ask would be “what are my odds of reaching my destination alive” and here airlines, er, crash and burn against land transport (except possibly motorbikes!).

Hmmmmmm, I’m not so sure you didn’t completely make up that number…

“Large commercial airplanes had 0.27 fatal accidents per million flights in 2020, To70 said, or one fatal crash every 3.7 million flights — up from 0.18 fatal accidents per million flights in 2019.”

https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-airlines-safety/aviation-deaths-rise-worldwide-in-2020-even-as-fatal-incidents-flights-fall-idUKKBN2962OA

Isn’t that a 50% increase in risk? (from 0.18 to 0.27).

And that’s relevant when comparing to road fatalities how? Isn’t the fundamental question how much risk we are willing to tolerate for a benefit, and at what cost? From a strictly safety standpoint air travel is insanely cheap for how few accidents there are.

The airplane did exactly what it is supposed to do but the PW engines in it have way too many failures. And let‘s be clear while such incidents can be contained each incident has still a significant risk of causing catastrophic failure. Eventually something bad will happen and considering the age of these engines, the pattern of failures, their gigantic power and their hollow blade design it is worth taking a break right now.

I think this is a crucial factor in the failure in Europe in particular to control Covid. Its only now – a year into the pandemic – that most European countries are getting serious about limiting travel and quarantine. The data from Ireland is telling – its now clear that all three of the waves that hit here were directly associated with waves of travellers. So while the government was willing to annihilate the hospitality industry to protect everyone, the airline industry was allowed to keep operations open to a ridiculous extent – even flights to holiday islands like Tenerife. While there was greatly reduced travel, you only need a few super spreaders, especially when it comes to the new variants. Like the UK, Ireland is only now getting really serious about travellers in a way which has been absolutely normal in Asia for 11 months now. Its hard not to conclude that this was primarily due to the lobbying power of the aircraft industry relative to other sectors.

Curious if there are any airlines that own their planes outright? Are aircraft financing and leasing considered to be part of OPEX or CAPEX in this industry?

Pre-Covid, Delta’s business model was oriented to operating older, but cheaper to acquire, planes. And pre-Covid Delta was the most valuable airline company—so it (assuming high jet fuel risk) worked pretty well for them.

But do they buy them to own them outright, with no interest payments at all?

without looking at the balance sheet, my guess would be that given low rates and financial markets backstopped by the Fed (pre-covid) there was little incentive, beyond cultural aversion to debt, to own your planes outright.

better to use your cashflow to buyback stock, see United

thanks Fed!

So I was reading years ago that a major problem for the airline industry was that too many planes were simply too old. With demand dropped off a cliff, you would think that an ideal solution would be to retire the older planes as well as the hanger queens that take too much maintenance. And in an ideal world it would be. But we don’t live in that world. The problems crops up about the planes that you have left. The Boeing 737 MAX should have been poised to take a leading position but that has not worked out for reasons better left unsaid. And then there is the growing awareness that Boeing planes built in South Carolina are being built by an unmotivated, second tier workforce simply as a way for Boeing to avoid unions and have, ahem, quality issues. The Chinese and Russian airliners are not up to scratch and Airbus can only ramp up production so far. So simply keeping the newer airliners is not always the solution that you think that it should be.

The longer version of the article makes it clear that the airlines burned the furniture to keep the house heated. They have used everything for collateral and are probably not in a financial position to retire anything. “In March, Congress provided $50 billion to the industry through the Cares Act … and allowed current owners and managers to raise an additional $40 billion from lenders who had been effectively told that they did not have to worry about bankruptcy risks … and ended up pledging almost every unencumbered airplane, airport slot, trademark, and route authority as collateral and paying interest rates as high as 10 percent.” The result will likely be dire, “… if … conditions do not rapidly improve, ongoing cash burns and asset erosion could make it impossible to salvage these businesses or achieve a strong recovery”.

Looks like it’s time for another $100 billion “investment” of taxpayer money into the airlines’ C-suites. It happens every 4 months like clockwork. Must be nice to be a donor to the Dem party.

Will someone ask FDR Jr., uh Joe Biden, why we “can’t afford” to clear out student debt but we have tons of money for air carriers?

The biggest problem the airlines are facing is maintaining a competent workforce. Pilots take five to ten years of training and experience to reach the level where they are allowed to fly planes with 300 plus passengers. Muscle memory is an important factor and unlike musicians who have a piano to practice on pilots do not have airplanes in their garages. The same can be said for mechanics and technicians, skills are atrophying and skilled staff that are difficult to replace are getting jobs outside of the airline industry. The actual planes will not deteriorate in storage and the airports will not wither away. Governments should be in discussions with the unions of the skilled airline workers to implement a program that will allow aviation to safely return to normal. No doubt private equity and hedge fund vultures will be playing their destructive role with the distressed assets.

Why must aviation return to normal? There are no climate-friendly airliners that I’m aware of. Perhaps you have invented one that uses no steel, oil-based plastics, aluminium or fossil fuels in its manufacture and use. Please share your knowledge.

Totally on the same wavelength with you James. Subsidizing a huge workforce that is no longer needed … what could possibly go wrong?

Before the Boeing 707 around 1960 transoceanic travel was done on passenger ships that burned coal and bunker fuel (low grade oil). If the airlines disappeared off the face of the earth tomorrow transoceanic travel would still be an economic necessity and would be by ship. Business life will go on at perhaps a reduced level for both goods and people as it has for tens of thousands of years. Will Canadians escape their harsh winters by going to the Caribbean in droves every winter, yes they will. If not by air then by car or rail to Florida or Cancun and then by ferry. Will goods flow into and out of Canada for the foreseeable future, yes undoubtedly if not by air then by surface transport. Ships can be economically powered by nuclear power plants, planes cannot and will most likely be fueled by hydrogen which will be expensive and reduce traffic. Nothing will happen overnight but most certainly will over the next 50 to 100 years. Look at how humans have behaved in the past where change was made mostly as a result of avoidable catastrophes.

JUST WHY is all this travel “a necessity?” Maybe work-from-home and Covid travel restrictions are leading to “innovative” ways of “doing business” that don’t involve the carbon costs and subsidized losses of air travel: ‘Worse Than Anyone Expected’: Air Travel Emissions Vastly Outpace Predictions —The findings put pressure on airline regulators to take stronger action to fight climate change as they prepare for a summit next week. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/19/climate/air-travel-emissions.html?auth=login-email&login=email

As for the special people who smugly assert that they “can afford” to just jet off to Tenerife or New Zealand or Switzerland for variety and jollies, what if they had to pay the externalized costs that such activities entail? Half of air travel emissions are caused by 1% of the world’s population , https://www.lonelyplanet.com/articles/air-travel-emissions-high-emitters

How long would those billion-dollar loot piles last if the Few had to eat the real costs of their specialness? Wonder what kinds of work-arounds they might come up with, like “virtual reality traveling?” https://www.boatinternational.com/destinations/virtual-travel-tours-trips-vr-experiences–43207

Of course, since the Special Few own all the policy levers, the chances of reining in this and future pandemics or ending the gluttonous “travel” appetites are pretty slim.

Guess the long process of collapse (at a pace where the Few can insulate themselves from the worst of it) will continue to the ugly endpoint…

@Mickey Hickey — Wonder if you’re familiar with Kim Stanley Robinson’s “The Ministry For The Future” ?

I thought it was a good read and recommend it.

Before the Boeing 707 around 1960 transoceanic travel was done on passenger ships that burned coal and bunker fuel (low grade oil).

Partly true and party not

In 1950 I flew from the UK to Syria.

In 1953 we took a ship to Nigeria – My Last Ocean trip.

Flights to and from Nigeria were in Argonauts and StratoCrusers – Piston Engines passenger planes.

I believe my first 707 flight was in the early 60s.

Those slower piston engined planes were a lot more fuel efficient, too. Speed is expensive.

Oh my. This brings back memories. Flying around Asia in DC8’s in the 1950’s. Trans Pacific and Atlantic trips by passenger ship.

An amazing exhausting flight with several fuel stops from NY to Frankfurt in a Lockheed Connie. My second trip to Frankfurt was in the early 1960’s in a 707.

Ana in Sacramento

Business life will go on at perhaps a reduced level for both goods and people as it has for tens of thousands of years.

Humans have not been engaging in “business life” for tens of thousands of years.

Bunker C is highly toxic to animals and humans.

There is a reason it can only be used out of sight of the mainland.

Neither the author nor the commenters have considered a far more pressing constraint on air travel: climate change. There is no means to power large airliners without continuing to pour GHG into the atmosphere. If we are serious about combatting the worst effects of climate change – and the lesser effects are too late to do anything about – then most commercial flying has to end right away, just as private car ownership must. Nothing less will be remotely sufficient, and those two are merely the tip of the (rapidly melting) iceberg. I don’t think most people have the slightest understanding of the serious position humanity is in. To waffle about economic ways to keep the airlines in business is not even to rearrange the deckchairs on the Titanic but rather to order Full Steam Ahead.

If we are serious about combatting the worst effects of climate change

…we’re not.

But air travel is a part of the GDP, like “housing” which also is apparently “Full Steam Ahead,” so how can “we” even be considering doing anything other than shoveling more coal into the boilers?

Maybe there needs to be some tax accounting scam like allowing credits and deductions for every empty passenger seat mile? Works with the airlines’ and Boeing/etc. designs that keep reducing the seat pitch of steerage and even business class to cram more bodies into the fuselage floor plans of ever larger (“efficiency!”) jets. (Note the reverse effect in private and corporate and Military General’s “biz jets…”. where “luxury accommodations” are the sine qua non.

Back to fundamentals:

IS THIS TRIP NECESSARY? https://www.zazzle.com/is_your_trip_necessary_ww2_poster-228849834232605756D

From today’s links: Armchair traveling is a thing already, has been for a long while — https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/postures-of-transport Hardly any carbon involved in that kind of special experience.

The key sentence, it seems to me:

“Industry insiders are finally beginning to recognize the powerful linkage between border closures and the collapse of business travel.”

What does it take to be an “industry insider”?” Do you have to be able to spell correctly and count beyond twenty? Can I become one, with their salaries and their offices, and their total ability to see beyond the end of their nose? Anyone who has travelled on business could have told them that. What world are these people living in?