Yves here. In fairness to this short article, one thing it establishes, whether it intended to or not, is that it’s not easy to divine what the best balance between working at home versus working at the office might be for many enterprises. As a lowly consumer and small business person, it’s clear that there’s tremendous variation among companies as to how well they are making having a far-flung employees “work” for clients.

And despite the authors’ pointed neutrality, a large-ish survey of CEOs in the Wall Street Journal a few months back found that nearly all were negative on working from home and were looking forward to having their staff in a traditional office setting. Another lapse is the article acknowledges that employees with families (particularly kids not in school) can find it very difficult to be productive when working from home.

By Kristian Behrensm, Professor of Economics, Université du Québec à Montréal (ESG-UQAM), Sergey Kichko, Associate Professor, Department of Economics and Senior Research Fellow, Center for Market Studies and Spatial Economics, HSE University, and Jacques-François Thisse, Professor of Economics and Regional Science, Université catholique de Louvain and CEPR Research Fellow. Originally published at VoxEU

Containing Covid-19 has required more people to work from home, accelerating the trend towards telecommuting. This column uses a general equilibrium model to analyse the long-term effects of this trend, and finds that it may prove to be a mixed blessing. Working from home saves time that would be spent commuting but deprives firms of the benefits from information and knowledge spillovers. Firms use less office space, but workers require more space at home. Overall, GDP will likely be maximised when working from home occurs one or two days per week.

Since the 1980s, firms have experienced new organisations of labour in which the flexibility of ‘where the work can be done’ is a major feature (Spreitzer et al. 2017, Mas and Pallais 2020). The trend in ‘telecommuting’ – also known as ‘working from home’ (WFH), and defined as work tasks performed from home or satellite offices one or several days per week – has accelerated during the Covid-19 pandemic. While less than 5% of the US labour force regularly worked from home in 2019, and 5.1% in the EU in 2018, these numbers have jumped since March 2019: Telecommuting has finally arrived on a grand scale. One may thus wonder whether it is here to stay and, if so, what economic impact it might have.

Whether telecommuting will remain when the pandemic is over depends on the long-run benefits it provides to firms and workers, as well as whether firms will hang on to the infrastructure and costly tools for remote work. Understanding how telecommuting on a large scale may change wage structure and GDP requires a model that allows us to analyse the effects of remote work on productivity and wages, the number of firms, commuting patterns, and the demands for goods, services, and housing/office space.

In a recent paper (Behrens et al. 2021), we analyse the wider economic impacts of large-scale telecommuting. Is it the boon advertised by its proponents, or the bane suggested by its opponents? According to its proponents, telecommuting cuts commuting time and costs, reduces traffic congestion and the emission of greenhouse gases, contributes to a better work-life balance for workers, and allows firms to save money on office space in large cities where rents have skyrocketed. Telecommuting’s opponents, on the other hand, stress the fact that workers’ isolation may have negative effects on their productivity due to interference between work and family responsibilities and the lack of contact with co-workers (Rockmann and Pratt 2015). There is no clear consensus on important questions such as whether telecommuting makes workers more productive.1 Consequently, there is even less consensus on broader questions such as the wider economic effects that telecommuting may bring about.

Our model encapsulates the key ingredients and trade-offs that we believe are important to better understand the broad effects of an increase in telecommuting on both GDP (efficiency) and the wage structure (equity).

First, telecommuting obviates the need to travel physically from home to the workplace. This form of commuting is very time consuming (in 2014, an estimated 139 million US workers spent a collective 3.4 million years commuting; see Ingraham 2016), accounts for a significant share of workers’ expenses, and is reported to be one of the most unpleasant activities in an individual’s daily life. Reducing commutes frees up resources and is likely to increase total hours worked. On the other hand, and equally important, productivity benefits that arise through face-to-face interactions in the workplace and in dense central cities will likely be foregone in the decentralisation of work. The existence of these agglomeration economies – productivity increases with the density of economic activity – is empirically well documented and is due, in part, to knowledge and information spillovers through face-to-face contacts among skilled workers that are very localised within firms and central cities (Liu et al. 2018, Rosenthal and Strange 2020). These agglomeration effects that drive central-city productivity will be negatively affected if the number of skilled workers in business districts shrinks significantly. Since telecommuters do not benefit from those various effects, the existence of agglomeration economies should hold back telework. The first key tradeoff of the model is therefore the saving of commuting costs versus the foregone agglomeration economies.

Second, the effects of increasing WFH will percolate through changes in the production and consumption of buildings: More WFH reduces firms’ demands for office space but increases workers’ demands for living space since additional room is required to work from home (in the long run, most people won’t want to work in their bedrooms). In other words, wired workers need more space at home, which affects location choices and the residential construction sector. Concurrently, firms’ space requirements are strongly reduced, which also affects location choices and the office construction sector. As a result, the markets for land and buildings must occupy centre stage in research that aims to assess the global effects of telework on cities. Since real-estate and land markets are likely to adjust more slowly to economic changes than goods and labour markets, it is important to investigate both the short-run effects of telecommuting (when office and land markets have not yet adjusted) and the long-run effects (when the adjustments have taken place).

Third, how will telecommuting affect the distribution of income in the economy? There is a consensus in the literature that telecommuting characterizes predominantly college-educated workers and has a negative impact on individuals with low education or vocational training. It is thus likely to have substantial distributional impacts. College-educated workers and those in managerial and professional occupations are more likely to work at home and can do a significantly higher share of their work tasks from home. The highly skilled also suffer less productivity loss from remote working (Dingel and Neiman 2020), which should exacerbate income inequality.

We develop a general equilibrium model where three primary production factors (skilled workers, unskilled workers, and land) and three sectors (construction, intermediate inputs, and final consumption) interact to shape the economy. We study how different intensities of telecommuting affect the whole economy, paying particular attention to: (i) the reduction of commuting to the workplace in cities; (ii) changes in productivity brought about by the concentration of employment within offices and city centres; and (iii) the shifts in demand for larger residences and less office space, which triggers changes that percolate through housing and land markets.

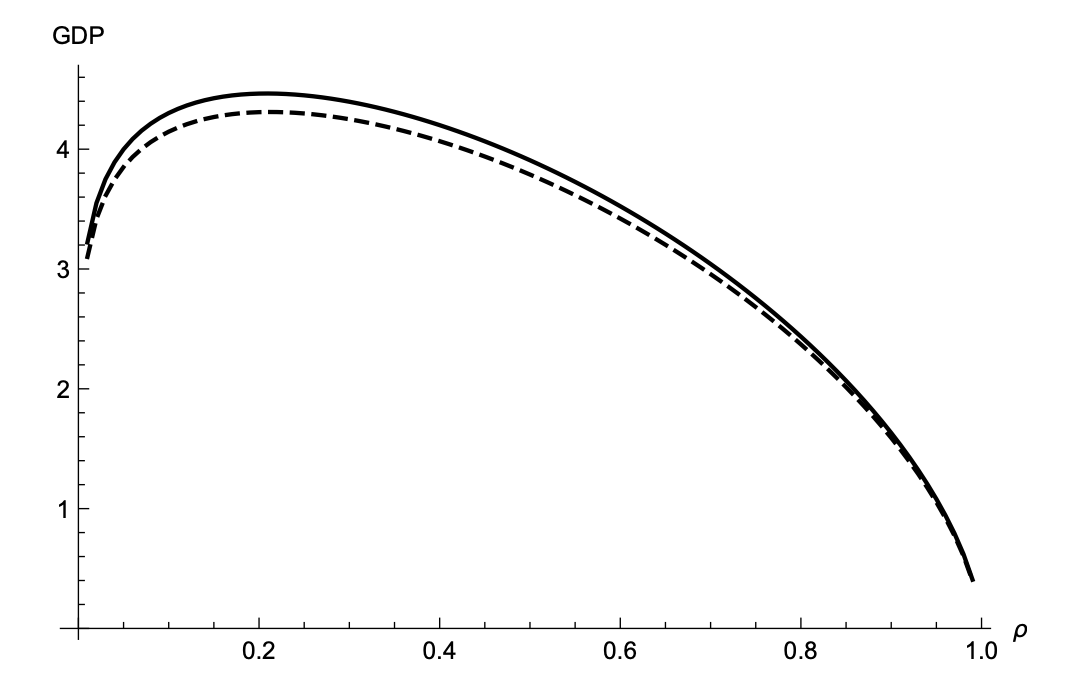

Figure 1 GDP as a function of the WFH share, two different simulations.

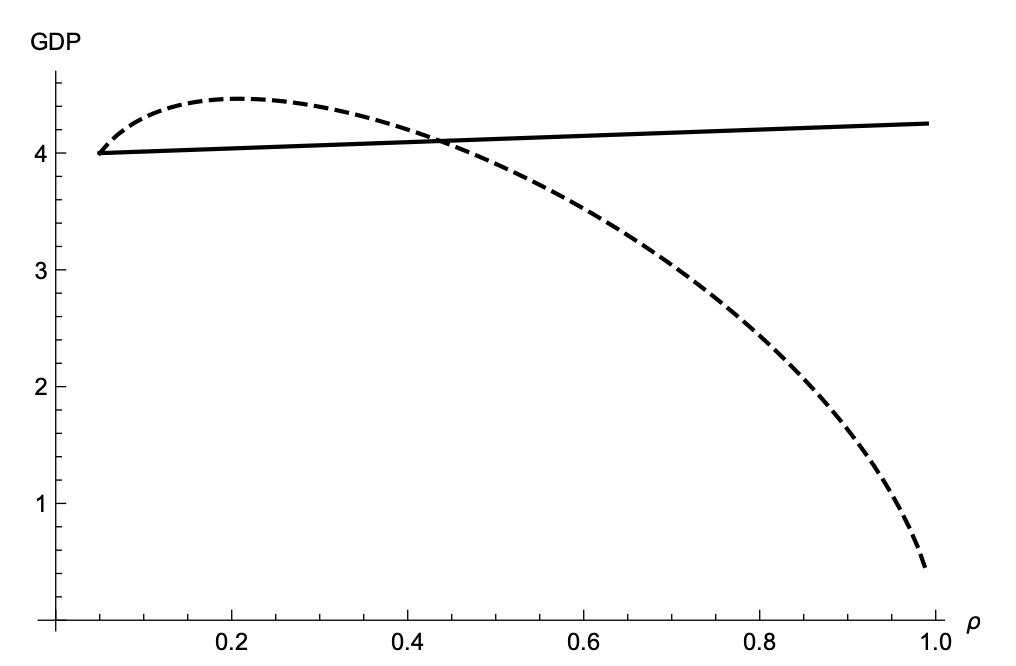

Figure 2 GDP changes in the short run (solid line) and in the long run (dashed line)

First, we find that the long-run effects of telecommuting are all described by bell-shaped curves: Telecommuting first increases skilled and unskilled workers’ productivity and GDP up to some threshold. Beyond that level, a higher share of home-workers reduces the strength of the knowledge and information spillovers which, therefore, do not produce desirable effects. Too much WFH may thus be detrimental to long-run innovation and growth due to limitations of information and communication technologies as well as foregone agglomeration economies in the form of face-to-face contact and knowledge spillovers.2 Figure 1 illustrates this point via some back-of-the-envelope computations using consensus parameter values. The WFH share that maximizes GDP varies between 20% and 40% in our simulations – one or two working days per 5-day week. This is broadly in line with recommendations made in human resource management (Gajendran and Harrison 2007).

Figure 3 Welfare of skilled relative to unskilled workers, two different simulations

class=”aligncenter size-full wp-image-198589″ src=”https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/00-working-3.png” alt=”” width=”600″ height=”384″ />

Second, Figure 2 reveals that the effects of telecommuting differ substantially between the long-run and the short-run: Whereas the former are bell-shaped, the latter are monotone. In the short-run, work dispersion implies an oversupply of offices, whereas the intermediate sector cannot produce a wider range of intermediates in the short run because new R&D investments are required. We find that GDP rises slowly and monotonically with the WFH share in the short-run; it is bell-shaped in the long-run. Hence, the short-run benefits may send inappropriate signals about the long-run effects of WFH when all markets have adjusted.

Lastly, Figure 3 shows that telecommuting will exacerbate economic inequality by making skilled workers better off than unskilled workers.

To conclude, we find that more WFH is a mixed blessing. The relationship between telecommuting and productivity or GDP is an inverted U-shape, whereas telecommuting raises income inequality. Hence, WFH at a large scale is likely to be too much of a good thing.

See original post for references

Won’t someone please think of The Economy! Translation: “The boss hates that it can’t sneak up behind you.”

Oh no! Won’t someone think of the GDP????

No… with software like ObserveIT & Citrix environments… they can track intent… no matter where you are…

“The boss hates that it can’t glare at you when passing by”, in that “you better be working your ass off or you’ll be out the door” look.

The war for top talent punishes managers and companies who behave this way

Your “top talent” are the managers who behave this way. In the real world everyone is replaceable. The war is between these managers (MBA’s) and the rest of the world.

You would think, but I don’t think they care. Changing their ways would force them to admin they’re wrong. Their egos can’t handle that. How many years did GE and Microsoft enforce “rank and yank”?

A key variable that hasn’t always been fully understood is that most offices are on fairly long leases. Core decisions on work arrangements only get made when companies are within a year or so of having to decide on whether to stick or twist with their current contractual obligations. I know one major company here that halved its office space last summer on the basis of home working, but that was mostly opportunist – the lease was up, and it seemed an easy way to save a lot of money by semi-formalising the lockdown work from home arrangements. Its not just the cost of floorspace, a lot of office contracts include provisions for heating and lighting, and so companies find themselves paying to keep empty offices fully serviced, so there are almost no savings whatever from home working. So I don’t think many companies will be under a lot of pressure to make quick decisions on this, unless they have a big lease renewal pending, they will hold on for as long as they can before deciding what to do.

A key long term question is the one about the value of informal connection and agglomeration benefits. Its long been recognised by economic geographers that agglomeration effects are absolutely central to the success of big, prosperous cities. There is a very long established straight line correlation between size and density of urban area, and productivity and creativity (however you measure it). This is one reason why most big cities thrive long after the original reason for their foundation has passed into history. But it can be argued that we’ve passed a tipping point where this benefit is no longer as clearcut. I’ve noticed with people I know who work for companies with multiple offices that they don’t really distinguish any longer very much between their colleague or manager who works on the next desk or the one in Singapore or Atlanta. Distance really has become much less relevant. I suspect that if we’ve hit the tipping point where physical proximity is no longer a major determinant of productivity, then we will see fundamental changes in urban geography, and maybe the international distribution of workers and wealth.

One last point that is anecdotal. My own organisation has reported, somewhat to its surprise, that productivity actually increased last year. Much of this of course may only be a temporary phenomenon. I’ve had multiple complains by colleagues about how much they miss the casual coffee break conversations that allow them to talk over problems and help them come to decisions. But there is another side to office life – the brown nosing and casual bullying and constant competition over pecking order. It may be that distance working is actually a bigger handicap to the office politicians, and a benefit to those who provide real objective value. It may represent the victory of introverts over extroverts (I’m not suggesting that all extroverts are brown losers, but it certainly helps your cause if you are better at social skills than your actual professional skills). This may well come to be seen as a hidden benefit of more home working over time. But as most CEO’s got to where they are through, well, being buddy buddy with the right people, this is probably something that is invisible to them.

Just want to pick up on one of your points. We shifted some of the staff to working from home. Becuase of that, it became quite obvious quite quickly that someone who was well liked had subpar work, the rest of the workforce was no longer there to make up for poor skills. The tide had gone out. Those covering the shortcomings were no longer willing to do so.

Second finding that came to light is inadequate office space. Too many people were crammed into small cubciles in bullpens. It’s actually not pleasant to work in.

Last finding – being distant forced us to find new ways to communicate. Communication actually improved because of the institution of a daily zoom to touch base with everyone.

Or not invisible to said CEOs, because as you said: “is actually a bigger handicap to the office politicians”.

Who are they but the most successful workplace politicians? It’s surprising that how many of them are not real bright, but still the vast, vast majority of CEOs are far from stupid and I have no doubt they see this.

Yet being smart and still being blind in the sense of “their paycheck depends on not knowing it” leads CEOs to really think that 40hrs at a very minimum and 60hrs (“I do it why can’t you?”) is necessary to “get things done”.

But the things most corporations “get done” are more burst-level activities at best. As a s/w engineer i find that 60 hr weeks are necessary in bursts but yearly productive hours don’t even come close to the time scheduled for being at the desk – and that’s accounting for vacations and holidays.

Thus we sit at our desks and wait for an email to come in and otherwise try to look busy. And everybody really needs a break after the “burst” time but we’re afraid to just demand it — and we can’t even properly use our time off for it because they want us to schedule longer-than-a-day vacations well in advance and Christmas Day is Christmas Day whether that’s a good time for you or not.

PlutoniumKun: You make a major point–“It may be that distance working is actually a bigger handicap to the office politicians, and a benefit to those who provide real objective value. It may represent the victory of introverts over extroverts (I’m not suggesting that all extroverts are brown losers, but it certainly helps your cause if you are better at social skills than your actual professional skills).”

I work in publishing and opted out of the office some thirty years ago. Editors/writers truly don’t have to be in a cubicle-filled office. But in the U S of A in particular, the plantation-overseer mentality means that many bosses want the staff to be around to benefit from being supervised. This mentality also explains why U.S. companies are so top heavy–smashing the employees in the office and then pad the managerial hierarchy, which one ascends, as you note, by daylong politicking and gladhanding.

Likewise, there’s the sheer amount of time wasted on displays of dominance plus various training sessions. In publishing, many horribly bad software programs are used for tracking progress, generating paperwork, and so forth. Everyone is required to be trained on management’s latest software savior.

Finally, my latest position was with a publisher headquartered in New York, and I live in Chicago. So I didn’t report in often. Further, and this is why working from home is not going to go away, the publisher had moved from an office building in the 20s in Manhattan way downtown, so far downtown that commuting was more difficult (imagine the logic of moving farther away from Penn Station). Yet the building was ultra-prestigious. So you also have U.S. management and its Mad Ludwig edifice complex forcing people out of the office. Then the company decide it would have on an open-office plan in UltraPrestige Tower. Employees were already maximizing WFH days several years back, and COVID cleared the place out. So you have a series of managerial mistakes now compounded by astronomical rent.

My experience is anecdotal, but maybe will add something. I am in IT and have always loved working from home. Granted I have never had children!

I got my first experience of it, 2 days a week back in the mid-90s and did very well; I could get the same amount of work done in 2-3 fewer hours than in the office with all of its distractions. As an introvert and someone who always hated the workplace political games, I was also happier being away from all that.

I think the article is too cute, too much invested in &$)*&” models, and I think that is the wrong approach. If they truly want to find out about what’s happening they will need to get out more.

I am not even mildly academic but I can think of many more things factoring into it. Some examples from my WFH experience this time around, which is 95% WFH since last March (I sometimes have to do field work like installing phones):

the businesses that used to cater to all the commuters are not mentioned. Maybe tangentially, they mentioned “unskilled workers” which looks to be a big bucket meaning “people who can’t telecommute” but it doesn’t speak to the coffee shops and lunch shops and other places we used to go in town.

Not every remote worker nor even most I would think, is going to get a bigger house or add on; as desk workers all one needs is a flat surface big enough for the modern small footprint computers, and a good chair.

Some people truly cannot work well at home regardless of lack of distraction etc., they need the discipline imparted by the workplace….my first husband couldn’t back in the 90s (although he got much better at it later).

With regard to those institutions that got top-heavy in the management tier: this has had at least a few good results that I know of…we are somewhat top-heavy and after the first push in the project to get people working from home, some managers were at sixes and sevens finding some purpose (not in our IT group, they were busier than ever since we were the ones getting the remote infrastructure installed, configured, and rolled out) and either left or switched jobs.

Very much agree that productive but shy people finally got the right environment to shine, and non-productive ones that hid behind their social skills were finally called out. Not to toot my own horn but I have been in IT long enough to acquire a lot of experience and I can get lots done, and also find creative fixes. In this past year this has finally become apparent to my bosses …I have received more kudos this year than almost all the previous 9 years at this position.

Good and bad, though, for the newly hired, they did not have the support needed to learn their jobs better. A few shone, that were already very good technically, but the younger ones who are still broadening their skills are still drowning a bit and I try to help them as much as I can.

Finally.. I will say that even an introvert like me is missing the person to person interaction, but that’s due to the fact that I can’t go out after work! If I were working from home without the pandemic context, for me at least it would be heaven.

Where I work, the staff has been working a mix – sometimes at home, sometimes in the office, particularly when needed. The managers have mostly stayed home, though. I suspect that they’ll want to pull everyone back into the office at some point, otherwise people might get it in their heads that the managers aren’t all that important to the whole thing.

I suppose that if you ask some economists to have a look at this question, it’s not surprising if their conclusions are all about maximising GDP. But there are a couple of more fundamental issues that need to be thought through.

The first is that “going to work” is a fairly modern idea. Until the late eighteenth century, you might work on somebody else’s farm, but more generally there would be no real difference between home and work, for craftsmen, shopkeepers and the like. As factories developed, communities were established around them, and walking to work was normal. Wives might take in washing, or scrub floors, but again this was within walking distance. “Commuting” was for the PMC of the day who wanted to live in nice places. Much of this survived until relatively recently: when I was small, my father walked to his (office) job every day. Most people lived only a bus or short train ride away from their jobs. But they had to travel, because there were things that were done there that could not be done at home.

In the UK at least, this started to change in the 1980s with the explosion of house prices and house ownership. Ordinary people doing mundane jobs faced an hour’s stressful travel each way, not because they had unrealistic expectations but because they could not afford to live any closer. Most people hated commuting: I certainly did. This trend has continued, which is why the authors’ suggestion that houses will have to get bigger to accommodate home-workers is risible: the houses don’t exist, and if they did they would be beyond the capacities of workers to buy.

Finally, “home-working” is a misnomer, or at least an over-simplification. The real issue here’s that employers can, for the first time in recorded history, keep tabs on, and demand work from, their employees at any time of the day and night, and in any location. Any real pretence of a gap between work and home, as commuting used to be, has long disappeared, and the working week has effectively increased to 144 hours. The “office” is now a largely virtual concept anyway. Anyone who has travelled on business will be familiar with sitting at an airport at 7 am, between flights, answering emails from people who are supposed to be asleep. In the long term, of course, working like this is bad for organisations: it destroys organisational culture, prevents collaboration and makes recruitment, training and promotion massively more difficult. But hey, never mind the quality, think of the short term benefits to GDP.

Yes, we forget about what a recent construction ‘work life’ as most people think of it really is. In particular, the notion that wives work the same hours and years as their husbands is even more recent.

It is simplistic to see the potential post-Covid world as being one where more people work the same hours from home. It could potentially change the entire nature of how we work and our expectations for a job and career. The problem is that the entire tax/pension/workers rights legislative framework is based upon an existing model, and may struggle to adopt to another one.

Of course, how it ends up will depend on the balance of power between companies and workers. We all know what major companies will want from this (although a few more progressive minded ones might not necessarily be too psychopathic about it). But it is important that Unions and other workers representatives react quickly to get ahead of the game. There have already been promising new laws giving more protection to workers in Europe, we can hope this continues.

At one job, 8 years ago, I refused a company cellphone. It wasn’t necessary for my job, which I said, and I didn’t want the expectation that I could be reached at any time or place (which I didn’t say).

Needless to say, there was astonishment that I refused a ‘free phone’.

I also only give home number, not mobile, to work.

I am the same – I set very clear boundaries around my work. Work gets most of my recovered commute time when I work from home (in exchange for some flexibility around appointments, breaks, household jobs and the like during the day) but aside from that I’m switching off at about the same time in both cases.

I am able to do this because I’m well established in my career and have a good feel for what I can push back on (and I pick employers who aren’t likely to try to abuse my time). I suspect if I was a new graduate I’d be much more inclined to accept the existing norms and go along with them.

It is simplistic to see the potential post-Covid world as being one where more people work the same hours from home.

This work-from-home applies only to the white collar world world of desk-type jobs, not to manufacturing, hauling, medical care, farming, animal processing, transportation, fishing, construction and fittings, cooking, and other such jobs.

Labor is labor. Just because someone uses a computer for their job doesn’t make them suddenly management.

@David “employers can, for the first time in recorded history, keep tabs on, and demand work from, their employees at any time of the day and night…working week has effectively increased to 144 hours.”

The “demand” for this is certainly not for the first time in recorded history, and neither is the ability to do so. The military has done this forever, and farm work famously has no break times. There are countless other examples.

That said, employees are supposed to negotiate working conditions, individually or through a union, not just roll over to random demands.

Management, of course, also plays into it.

I have managed a fairly diverse team for over a decade, and I encourage the people who work for me to power off their notepads and hide them in a closet where they will be unseen outside working hours.

I also tell them to power off their company cell phones outside working hours.

I do this not because I am a sweet wonderful human being, but because my experience is the ones who are sending me emails at 3 AM to impress me are the ones who burn out spectacularly and create problems for me in the long run.

Work from home is here to stay. It is clear from COVID-19 that most of these jobs don’t need to be done in an office. You can claim “social justice” because “feminism” and “promoting diversity” or something. Once you relocate work out of the office, and you get the system down, you can offshore to cheaper labor markets and drive down costs. I’m sure McKinsey and Co. has a group working on it right now. Further, you’re a racist and a COVID conspiracy theorist and your twitter account will be banned if you are critical of work from home initiatives.

I hope I am not violating the comments policy, but if we do see an outflow of white collar jobs being offshored as the final result of “work from home”, we may also see significant out-migration trends from the United States to places with lower costs of living and less predatory health care systems.

I’d argue that WFH has the potential to mitigate offshoring or, at the very least, will have little to no effect on it. Companies have had decades of experience with staff augmentation via offshoring models already. The only driver has been the illusion of lowered costs. Layoffs and redistribution of work to places like India and Eastern Europe were happening prior to the pandemic. That said, the pandemic being global has revealed localized liabilities such as inadequate responses by those governments and health agencies. It’s much easier for an organization to manage consequences of lockdowns in their own backyard with firsthand knowledge of what resources are available, such as broadband Internet.

Outmigration to another country will be limited, as there are high barriers to citizenship. Unless you’re sponsored by an employer, a long-standing spouse, or attached to enough capital to retire, desirable locales like the EU are simply unavailable to almost all of the US population. Countries like Germany or France have no desire to absorb the influx of US expatriates with little to nothing to offer the local economy, particularly those only seeking a sane healthcare system or looking to live off the largesse of a strong safety net. These are also countries looking for future residents with a serious inclination to assimilate to local customs and learn a second language. The schooling system in the US being so piss-poor means that second language competence is rare. That leaves non-Eurocentric locales such as South America, whose desirability is belied by the number of those who return to the US after a few years.

Insofar as mitigating offshoring goes, there’s already evidence of that happening vis a vis the migration of US residence from high burden states, like CA, to others like Austin, TX, Boulder, CO, or Raleigh, NC. With a reasonably positive WFH gain or simply neutral change, there’s the opportunity to use cost-of-living arbitrage solely on US soil. You can shed staff in Silicon Valley and compress wages by confining hires to places that have cheaper housing, etc. Lower employee costs while keeping the advantage of an identical culture and language.

While it is true that: “Companies have had decades of experience with staff augmentation via offshoring models already. The only driver has been the illusion of lowered costs. Layoffs and redistribution of work to places like India and Eastern Europe were happening prior to the pandemic.” I believe the recent Corona pandemic-induced move to telecommuting exposes an entirely new set of US jobs to consideration for possible moves to places far far away. Companies had decades of experience moving jobs to the US South to obtain:”Lower employee costs while keeping the advantage of an identical culture and language.” I suppose even more jobs could move to the South. I wonder how much advantage there is in paying extra for US workers with “identical culture and language” as the US. I think only some special kinds of work should feel safe with telecommuting. And though office leases are long-term, that suggests offshoring might lag as businesses finish out or find ways to break those leases.

Out migration for employees is harder than you might think, as it hits all sorts of tax and legal problems for employer and employee, this is why most companies are now insisting that work at home employees spend a minimum time in their country of employment, even within the EU.

I do think we’ll see out migration and off shoring. I also think we’ll see some professionals who think they should be able to work from home or in some nice locale and still keep their position with a salary adjusted for a high cost of living. That’s already been a rude awakening where I live. Some people thought they were the only ones who figured out that they could live anywhere and still work at their companies in this environment. Shortly afterwards, they were told by employers to come home or their companies would hire from places where the employees would be happy with 70% of their current salary.

See above, emigration to first world economies is impossible unless you have the right spouse or are sponsored by your employers or are independently wealthy (or are a student). Multinational employers post employees to foreign countries only if there’s a need for a body in that country, and the host countries monitor those arrangements.

I think we will certainly see more outflow of white collar, middle class jobs. I doubt that this will result in out-migrations. It is considerably more likely that corporate labor pool will trend to more non-US workers.

It will be a mistake to confuse migration of work with migration of workers. The current WFH paradigm is a bolt-on modification to the employer-employee relationship. Any conclusion or prediction based on it is moot and short-sighted. For corporations, the benefit of current payroll costs (salary, benefits and admin) by outsourcing jobs overseas will out weight the cut in productivity.

Totally agree about outmigration. I live on the outskirts of a city in Central México, a country where becoming a permanent resident and, eventually, a citizen is not at all difficult. There is a major flood of white collar people moving here from the US who apparently are making “work from home” permanent. It’s driving up the cost of living here, distorting the local culture and economy, overloading the infrastructure, and exacerbating an already serious water shortage. I’m leaving this place and heading further south because seeing this part of México become Americanized is not why I moved here.

As others have noted here, as an expat you *must* be able to pay your own way. Nobody has any time or charity for penniless Americans landing on their doorstep, least of all the local US Embassy. Living overseas like an American PMCer is if anything more expensive (health care aside) than the US, but in poorer countries men have the option of marrying a local citizen….

In the Philippines, a reliable fixed income of $2,500 per month allows you to live quite comfortably *as a Filipino*. That is to say, in a walled cement house in a semi rural town among your wife’s extended family who see you as part of their safety net. They’re prone to use you as an ATM, but your wife generally keeps that at bay. You’ll drive a motoscooter, not a car, unless it’s an in-law’s work vehicle that you’ve invested in. Forget about flying ‘home’ with any regularity. You’ll also have a pub network of other moldy old expats. Don’t bother trying to found a business in your own name; it’s open season for local officialdom to shake you down nonstop. Operate through your wife or a reliable inlaw.

Health care is, of course, the wild card. Local hospitals can handle most routine illnesses and injuries, but if you get the Big C you’re really gambling. Private health insurance giving access to modern hospitals the elites use runs about USD 12k a year per person, and there will be cash only expenses on top of that.

YMMV.

There is a conspicuous absence of people’s own preferences. One company I know did a survey and found a roughly equal split. One third wanted to keep home working, another third wanted back in the office while the final third wanted a split.

My own company was lucky that it’s lease expired last May, so we relinquished it. Now signed a flexible agreement with a company that took too much space a couple of years ago on a long lease. I think the challenge will be how to make flexible space arrangements work.

There are pluses and minuses. I think it subtracts from local economies, when work locations no longer need food service providers or catering on a previously larger scale. No need to throw a big lunch for closing the books !

I do like knowing when I leave the work place to drive home, generally my work day has ended. In the extreme I can log back on for a zoom or teams call at 7pm. But I’m not much good for critical thought past it.

I’d agree with that there is tremendous variation among companies of how well it works. And if there is a tremendous variation then I’d argue that a one-size-fits-all solution is unlikely to exist. Neither the 95% work from the office nor the 95% work from home is optimal, the likely optimum is somewhere in between and even there it might be about office-workers working a few days from home and a few days in the office.

One of the factors causing variation is the company size. An office worker for a large organisation may have strict processes to follow with few if any deviations to the process are allowed. An office worker in such a setting does not need to be close to collleagues to know what to do, the process is documented and there to be followed. Working from home or working from the office does not matter, the process is to be followed and informal information sharing might even be frowned upon.

A smaller organisation might not have so well documented processes and therefore colleagues might benefit more by being close so that they can ask each other for help, guidance and advice.

& I might be wrong but the conclusion that increased tele-commuting leads to increased income-inequality might be based on the assumption that workers are paid based on productivity?

If that assumption was made then I believe that the conclusion is wrong, people are not paid on what they are worth – they are paid what they can negotiate for. The threat of off-shoring might actually be a factor making the work-from home (skilled?) less likely to get salary increases.

Two surprising outcomes of working from home after a year of doing it:

1. I sleep significantly more, at least an hour more, each day. It’s greatly improved by mood and mental health.

2. I have time to work out, probably from the saved commuting time. This has made healthier.

Sick time is not much of a productivity loss both because I’m healthier and happier and because I can fit in the work when I’m not feeling well.

Figure 3 doesn’t appear to be displaying correctly?

A lot of this depends on the industry. I’ve worked from home/boat/beach for 20 years. There were years when I was in the office for 3 or 4 times a year for less than a week at a time. Add to that 3 or 4 work trips a year.

The company I currently work for has 90+% of the staff WFH. The handful of people in the offices are there because they didn’t have an environment where they could WFH for any length of time. The lease issue has been discussed and they have stated that given what they have seen over the past 11 months they will be encouraging a much higher percentage of people to WFH and reducing office size to match when the leases come up.

The company did twice make the rounds to ask what people needed at home to work more efficiently. I know of one person who said “doors on my den”. In the end the company twice added small amounts to everyone’s paycheck to cover whatever individual wanted. Oh, and they sent everyone a t-shirt. “I’m working from home!”

The company has also scheduled some social events, area by area, during the work day to build some camaraderie. The first time this was done the event was scheduled at 5:00 and someone up in corporate who was not attending, sent an email rescheduling it for the mid-afternoon so it would end at 5:00. Something about HR saying we can only require people to enjoy themselves on our time, not their time.

What people have noticed is that while there are attempts to deliberately communicate more, there in is no walking down the hallways and running into someone asking what they where working on and saying something like :”Oh, you should look at x or talk to y because they did something similar”.

Funny thing, the Feds, having a certain interest in the company, have shown up, virtually, I assume, and have and strongly suggested fewer people in the office going forward as that would lower the risk if something bad happened.

Figure 3 is not displaying as it should. There appears to be an error in the “class” string that’s supposed to bring it into the post.

I think it’s pretty clear that the people and jobs who really allow us to function as a society, and as humans, cannot EVER work from home. Thus we have been treated to the paeans to ‘essential’ worker heroes. But nonetheless, we need food, deliveries, trucking, fuel, medicine, the basic things of life- you know- things one actually needs to survive. There is no question of their ‘working from home’.

Maybe we can borrow a bit from Mr Graber and ask (and of course this isn’t entirely true, but it’s fun to ponder!) “if your job allows you to work from home, you may, in fact, have a Bullsh*t job”.

“if your job allows you to work from home, you may, in fact, have a Bullsh*t job”.

Despite being squarely in that category – I have been WFH off and on for much of the last 15 years, 100% WFH for the last 6 years – and i couldn’t agree with you more.

Yes, in a certain economy where there is time for bells and whistles, frills and dressings…sure, I contribute a lot of ‘work’ that makes for a lot of value to corporations…with a reasonable amount trickling down to me too.

But in the kind of scratch and scrape economy we are headed to…..one had better be able to insure ones back is strong, and ones hands are not soft, if ya know what i mean. I was raised dirt poor on a family farm (which is still, amazingly, in the family even after all these 100 years) so I am no stranger to ACTUALLY working for a living.

Zeus grant that I never lose my Sisu, when the time comes to improvise, adapt, and overcome….

‘When energy constraints come into play, old work habits will make your’s .. mine .. and everyone else’s a new day!

Hope your family farm wasn’t in the UP. I still have a letter from a now deceased farmer around Point Abbaye, who, when he heard I had gotten a horse, seriously wrote me that “…it is very important not to tire the horse.” That sentence was worth a chapter in any back to the land fantasy. Sisu indeed. Oma Tupa, Oma Lupa.

I just added Sisu to my collection of new words. Thanks! But I worry about the value of Sisu if we lack a Pathfinder.

Yep, your last sentence has crossed my mind many times. It’s true but only for about 50% of my work. The other 50% has to happen or people lose their jobs.

That said, I imagine that many people with NON bullshit jobs, like nurses, actually spend about half their time on bullshit tasks, like coding and billing and memorizing numbers and doing paperwork.

What I’ve seen in the Bay Area is, all the charming small towns from the Central Coast to the Sierra being turned into overcrowded boutique bedroom communities. Truckee, the mountain town where my family has modestly vacationed for over 30 years, is in the process of rapidly doubling in size and, I daresay, tripling in preciousness, no longer accessible or appealing. The PMC bring their attitudes…skimming the cream of the quaint charm and erecting their own fine dining establishments, golf courses, and gourmet cupcake shops.

I see my friends, and my children’s friends, scattering. This feels like another aspect of “creative disruption ” to me, emphasis on disruption. Human bonds have already felt too fragile around here. I wish we could stick together; stay put; commit to community-building where we are.

Do you see this as overflow population pressure from the Bay Area, or due to rising inequality, with the PMC merely purchasing second homes in Truckee? Or something else?

One of my nieces, employed by the Greater London Council his in the process of relocating to Glasgow, because of the ability to work from home with much lower cost of housing virsus the enormous cost of housing in Lindon.

My Sister lived in the in Hackney area for 50 years, bought her first house in1973 for about 14,000 Pounds, her second in 1980 for 70,000 pounds, her third for 620,000 pounds in 1996 and just sold her third house for 2,800,000 pounds.

As for the Comment about about Raleigh NC, I bought a house there in 1988 for $115,000, and it is now valued by Zillow for $1,000.000. My first house in the US was in Oakland, cost $175,000 in1982 and is currently valued at $1,000,000.

Low inflation? I think not.

I’d assert that interest rates are a huge in house prices.

@Synoia

February 13, 2021 at 1:14 pm

——-

Your last sentence is missing a word, which looks to be something like “…huge *factor* in house prices.”

I agree completely.

I think it is Michael Hudson who has said many times that the price of a home is mainly determined by how much a bank is willing to lend to the buyer. Since increasing prices means increasing mortgage interest, the banks have an incentive to continue lending ever-larger amounts for each subsequent purchase to increase their interest income, with due consideration to the location and condition of the neighborhood.

I believe this is a major reason why the percentage of people’s income devoted to housing has increased from around 25% to 40-50% for many homeowners and renters (the landlord also has increasing mortgage servicing costs) over the past 40 years.

The banks are trying to capture as much of that income in interest payments as they can.

Hudson is so right. This basially secures an endless cash stream into the banks as well as remorae like title companies and law firms and national wide realty agencies

This one is easy imo:telecommuting for me . The mines for you.

God forbid we consider the carbon costs from thousands of employees stuck in traffic everyday. Heavy clapping for performative “green” initiatives like recycled utensils in the lunch room.

Neither carbon costs nor the time waste and frustration of commuting in heavy traffic has helped much for mass transit — although it did lead to a small industry of studies.

Worth putting into the discussion I think, is the following summary of research (?), retweeted by the always worthwhile Chris Dillow @CJFDillow, whose remark about the retweeted item was: “I’m pleased to be wrong here. I had thought there’d be more corporate resistance to remote working.” https://twitter.com/chris_herd/status/1359135080753614854?s=20

“productivity benefits that arise through face-to-face interactions in the workplace”

You mean like those coffee breaks, and mindless chats with colleagues?

Knowing your colleagues may produce productivity benefits (trusts is shown as the best team productivity lubricant, and you can’t have trust w/o knowing people). That said, it’s possible to know your colleagues reasonably well remotely – I know quite a few commenters here, and never ever met them. It just takes more time. Very large open-source projects were done by people who never met each other. Scientific teams work remotely (from each other) sucessfully (and worked when the fastest communication was a letter carried on a horseback).

The reality is, as has been said elsewhere a number of times.

IMO, a productivity of WFH depends on there elements:

– type of the work. Some work is easier to do remotely, for some face-to-face productive meetings are extremely useful.

– type of the person. Yes, it very much depends on the person him/herself. Some hate it, some love it.

– the team one is working in. With a plantation-supervisor boss (I stole the term from comments above, and like it), or people doing office politcs more than work, or team where turnover is constant and no-one lasts long, it will never work. For stable teams of people who know each other well, it will even in industries that normally people would not expect to.

On a separate note, WFH definitely has a redistributive effect, where many of the office-area-shops would die. (and many already did). But local ones are picking up, at least where I live, so it’s not like the money is not spent (when it’s there). Yes, some people will lose jobs. But at the same time, those are often low-paid jobs in high-cost areas. Is it not better if we had similarly, or even slightly better paid jobs (job market in small towns are way tighter), in lower-cost areas?

Let’s just not work. At home or at a desginated place. The cult of work is the one thing that bring together every horrid ideology from Naziism to Soviet Communism to Ayn Randism. They are all very concerned to put YOU to work. Until the day you die.

As “Bob” Dobbs says, “Repent. Quit your job. Slack off.”

Something to contemplate while elevating the head of the pro golfer. “We all crave slack.”

One of the two major employers in my area – a medical center – has already decided WFH is here to stay. They can eliminate a lot of leased property, and don’t have to add parking (or so they hope) for a new inpatient facility that will add 500 employees. The other, a university in all but name, is “studying” the issue. There are similar advantages – eliminating rental space, reducing the pressure on parking – and also benefits for recruiting. Getting people to move to a rural area with outrageous housing costs is a perennial challenge.

A friend of mine works for another university. They plan to continue WFH after the pandemic and are actively working to determine who really needs to be on site, and for how much time. My friend lives in the local area. His employer is several states away. He figures at most he might need to be on site a couple of days a month.

Me, after a year of WFH, I’d happily continue to do so. I get a lot more done both for work and around the house, and even though my commute is a pleasant drive down country roads for the most part, I don’t miss it. A number of people I work with have mentioned that it’s fun to get a little insight into others lives – kids and pets randomly wandering into zoom meetings, babies, puppies and kittens being introduced.

Not sure if I’d feel the same way if I had young kids. WFH has been difficult for all of my co-workers who are trying to balance child care, home schooling and work.

I’ve been working from home since that Downtown Tucson coworking space closed in the summer of 2019. I’m finding that I am ever bit as productive here as I was there, and you can’t beat the commute. I also don’t miss dealing with leases, landlords, paying rent, and office politics. I especially don’t miss the office politics in that place.

Biggest downside of working from home? Barking. Matter of fact, my ears are being blasted right now.

I mean, come on, neighbors, how hard is it to keep your dogs quiet? If it is difficult, then maybe you shouldn’t have a dog.

Hey Slim. Is getting a dog whistle an option to break up those dog’s barking? Don’t know how well they work but it might be an option.

No it isn’t.

You need a direct line of sight between you and the dog. Not the case here.

Slim … all you need is a customized programmable racing-rabbit drone that will wear those little doggies ragged!

I’m a headhunter and that informs my view of wfh. I’m already seeing wfh being viewed as a benefit along side 401k plans. Employers that don’t offer this Post Covid will be viewed unfavorably no matter what their leadership team believes. Employers that don’t at least offer part time remote work when possible are going to have a more difficult time attracting and retaining top talent.